Leadership Focus journalist Nic Paton takes a look at the early career framework (ECF) and how it is supporting, developing and progressing early career teachers.

“Teachers are the foundation of the education system – there are no great schools without great teachers.”

So begins the Department for Education’s (DfE’s) 2019 document 'Early career framework', setting out the basis for a new framework, methodology and approach for supporting, developing and progressing early career teachers (the new name for newly qualified teachers).

The new mandatory two-year induction period, which came into effect from September 2021, would, the DfE argued, “build on high-quality initial teacher training and become the cornerstone of a successful career in teaching”.

These are words that, of course, few head teachers or school leaders – probably none in fact – would disagree with. Indeed, as NAHT senior policy advisor Ian Hartwright points out, the profession was by and large on board with the principle of, and need for, this kind of early career development, not least as NAHT had been closely involved in the genesis and initial planning of the framework.

IAN HARTWRIGHT

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISOR

“We broadly agreed with most of the content in it. It’s a bit too prescriptive from our point of view, but overall, we felt it was OK. Most importantly, the DfE had agreed that the cost of early career support should be fully funded,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“Teachers are the foundation of the education system – there are no great schools without great teachers.”

So begins the Department for Education’s (DfE’s) 2019 document 'Early career framework', setting out the basis for a new framework, methodology and approach for supporting, developing and progressing early career teachers (the new name for newly qualified teachers).

The new mandatory two-year induction period, which came into effect from September 2021, would, the DfE argued, “build on high-quality initial teacher training and become the cornerstone of a successful career in teaching”.

These are words that, of course, few head teachers or school leaders – probably none in fact – would disagree with. Indeed, as NAHT senior policy advisor Ian Hartwright points out, the profession was by and large on board with the principle of, and need for, this kind of early career development, not least as NAHT had been closely involved in the genesis and initial planning of the framework.

IAN HARTWRIGHT

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISOR

“We broadly agreed with most of the content in it. It’s a bit too prescriptive from our point of view, but overall, we felt it was OK. Most importantly, the DfE had agreed that the cost of early career support should be fully funded,” he tells Leadership Focus.

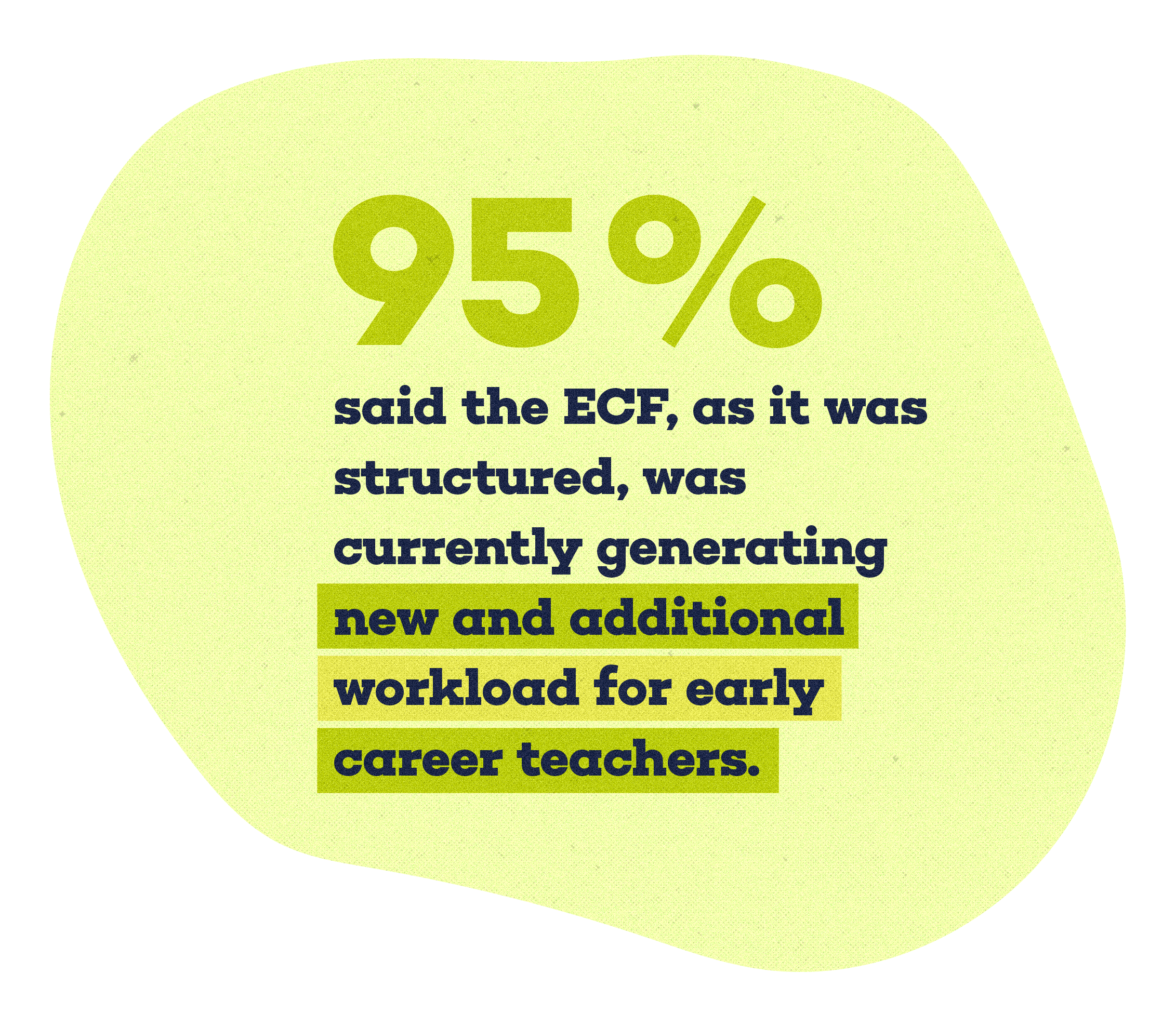

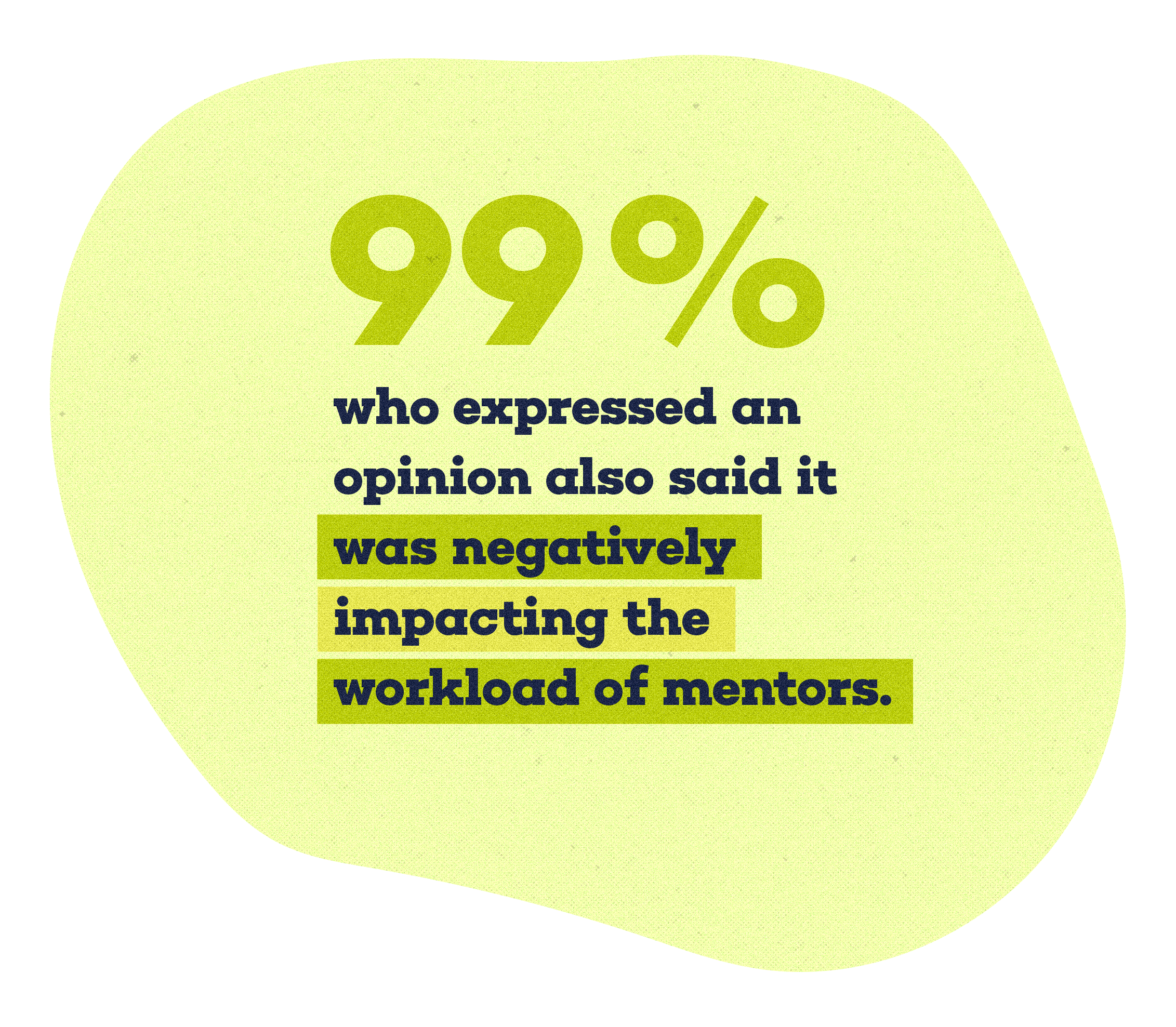

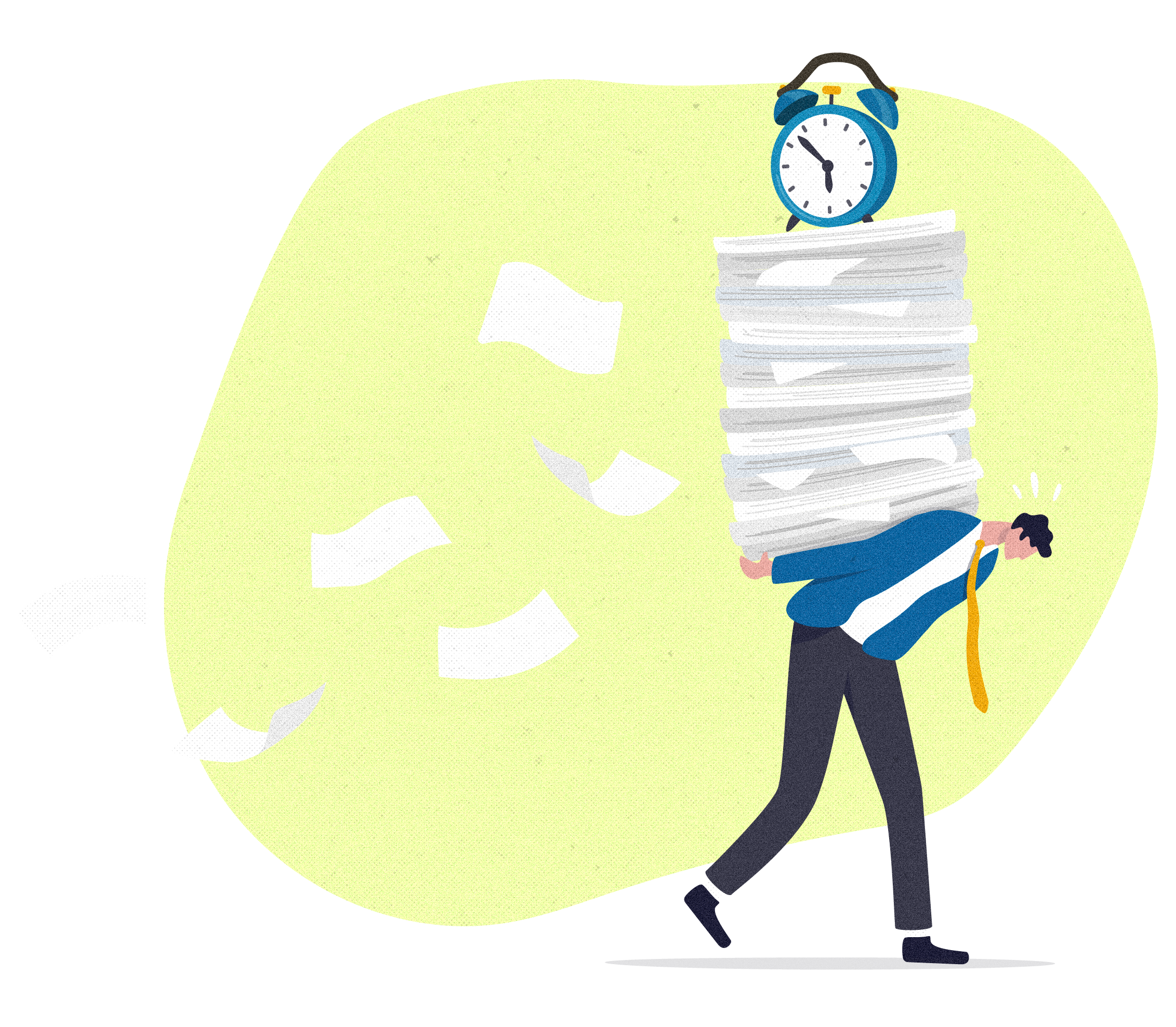

More worryingly, an overwhelming majority of school leaders (95%) said the ECF, as it was structured, was currently generating new and additional workload for early career teachers. Almost all (99%) who expressed an opinion also said it was negatively impacting the workload of mentors.

“This threatens the policy intent of underpinning the longer induction period to the extent that it could exacerbate rather than improve early-career retention rates,” the survey argued.

The good news is this is not totally a ‘what went wrong?’ story. The government (arguably unusual for this administration) does appear to have sat up and listened to the concerns raised by NAHT. It is now in the process of revisiting some aspects of the ECF. As Ian puts it: “Through lots of lobbying, lots of discussions and some really quite hard conversations – and by asking our members and because they responded in such numbers – we have been able to persuade the DfE that some change is necessary.”

So, what have been the issues with the ECF, what did NAHT recommend, what may be changing as a result and are there, in fact, alternative options or approaches that school leaders can use to mentor, support and develop their early career teachers?

Taking the problems with the ECF first, Ian argues that some of it comes back to the ministerial revolving door we’ve seen at the DfE during the past three years.

More worryingly, an overwhelming majority of school leaders (95%) said the ECF, as it was structured, was currently generating new and additional workload for early career teachers. Almost all (99%) who expressed an opinion also said it was negatively impacting the workload of mentors.

“This threatens the policy intent of underpinning the longer induction period to the extent that it could exacerbate rather than improve early-career retention rates,” the survey argued.

The good news is this is not totally a ‘what went wrong?’ story. The government (arguably unusual for this administration) does appear to have sat up and listened to the concerns raised by NAHT. It is now in the process of revisiting some aspects of the ECF. As Ian puts it: “Through lots of lobbying, lots of discussions and some really quite hard conversations – and by asking our members and because they responded in such numbers – we have been able to persuade the DfE that some change is necessary.”

So, what have been the issues with the ECF, what did NAHT recommend, what may be changing as a result and are there, in fact, alternative options or approaches that school leaders can use to mentor, support and develop their early career teachers?

Taking the problems with the ECF first, Ian argues that some of it comes back to the ministerial revolving door we’ve seen at the DfE during the past three years.

“The whole conversation about an ECF informed a key element of the DfE’s '2019 Teacher recruitment and retention strategy'. The department, quite rightly, wanted to reduce workload and better support early teachers to make teaching a more attractive and sustainable career option – something we at NAHT fully supported,” he explains.

“From our discussions, what we said teachers needed was more support in their early career and more opportunities for continuing professional development (CPD); in fact, they need CPD throughout their career, but this needed to be the first step. We spoke to the DfE about working together to create some kind of early career support.

“They agreed in principle, and we were able to sign up to it and put our badge of support on it. However, we emphasised the important word within all this needed to be ‘support’; it needed to be designed to support new teachers.

“The other thing we said was it mustn’t create additional workload, and whatever model put in place needed to be a fully-funded approach. Funding needed to be available not only for the training costs but also to cover their time off timetable, the mentor’s time and time off timetable, and the training time for mentors. After all, if this were an entitlement for every early career teacher, it would be quite a significant new strain or responsibility on the system,” Ian explains.

That was all well and good, except that by the time the framework emerged following agreement on the 2019 strategy, the DfE had been through a change of government and ministerial team. “What came back was an early career curriculum rather than a support package. So, it is something that early career teachers have to work through,” Ian continues.

“The whole conversation about an ECF informed a key element of the DfE’s '2019 Teacher recruitment and retention strategy'. The department, quite rightly, wanted to reduce workload and better support early teachers to make teaching a more attractive and sustainable career option – something we at NAHT fully supported,” he explains.

“From our discussions, what we said teachers needed was more support in their early career and more opportunities for continuing professional development (CPD); in fact, they need CPD throughout their career, but this needed to be the first step. We spoke to the DfE about working together to create some kind of early career support.

“They agreed in principle, and we were able to sign up to it and put our badge of support on it. However, we emphasised the important word within all this needed to be ‘support’; it needed to be designed to support new teachers.

“The other thing we said was it mustn’t create additional workload, and whatever model put in place needed to be a fully-funded approach. Funding needed to be available not only for the training costs but also to cover their time off timetable, the mentor’s time and time off timetable, and the training time for mentors. After all, if this were an entitlement for every early career teacher, it would be quite a significant new strain or responsibility on the system,” Ian explains.

That was all well and good, except that by the time the framework emerged following agreement on the 2019 strategy, the DfE had been through a change of government and ministerial team. “What came back was an early career curriculum rather than a support package. So, it is something that early career teachers have to work through,” Ian continues.

This sounds flexible enough, but the reality was a bit different in practice. As Ian points out, this was because the DfE had stipulated that the framework would only be fully funded if schools agreed to use the DfE’s providers (in other words, option one).

“It turned out to be much more formal,” Ian says. “Ministers wanted, in the DfE’s words, ‘fidelity’ to the framework. The appointed providers have set up a strict programme that early career teachers and mentors have to follow. It is done on a week-by-week basis, and there is homework to complete, things to read and evidence-based research to look at.

“Our criticism, and the criticism of other unions, is that this isn’t flexible enough to reflect the realities of what happens in a classroom. Because as we all know, being a teacher is an incredibly dynamic role, and certain things will take precedence depending on what is happening in your teaching role. For example, your year nine class might have behavioural issues that you are contending with; it might be you’re struggling to come to terms with how a particular area of what you’re teaching is assessed or the content of a particular part of the course.

“Mentors were saying they weren’t able to respond to the needs of their early career teachers. It was too inflexible and often not relevant to where that person was. The mentees, in turn, were saying a lot of it felt repetitive, like what they’d already done in their teacher training. Mentors were also saying it was causing a lot of additional workload, and new teachers were also finding it difficult to manage. Your first year of teaching is challenging enough anyway,” Ian argues.

This, then, was at the heart of the disgruntlement evident within NAHT’s member survey.

This sounds flexible enough, but the reality was a bit different in practice. As Ian points out, this was because the DfE had stipulated that the framework would only be fully funded if schools agreed to use the DfE’s providers (in other words, option one).

“It turned out to be much more formal,” Ian says. “Ministers wanted, in the DfE’s words, ‘fidelity’ to the framework. The appointed providers have set up a strict programme that early career teachers and mentors have to follow. It is done on a week-by-week basis, and there is homework to complete, things to read and evidence-based research to look at.

“Our criticism, and the criticism of other unions, is that this isn’t flexible enough to reflect the realities of what happens in a classroom. Because as we all know, being a teacher is an incredibly dynamic role, and certain things will take precedence depending on what is happening in your teaching role. For example, your year nine class might have behavioural issues that you are contending with; it might be you’re struggling to come to terms with how a particular area of what you’re teaching is assessed or the content of a particular part of the course.

“Mentors were saying they weren’t able to respond to the needs of their early career teachers. It was too inflexible and often not relevant to where that person was. The mentees, in turn, were saying a lot of it felt repetitive, like what they’d already done in their teacher training. Mentors were also saying it was causing a lot of additional workload, and new teachers were also finding it difficult to manage. Your first year of teaching is challenging enough anyway,” Ian argues.

This, then, was at the heart of the disgruntlement evident within NAHT’s member survey.

That survey made three recommendations:

“We said the DfE needed to reduce the workload involved with the framework. It needed to stop the providers from setting evening and weekend work. We said things needed to be more flexible and that it was proving difficult to roll out given all the other pressures schools are under. We also called for the framework to be more about supporting teachers than forcing them to follow a curriculum and this notion of fidelity,” Ian explains.

Positively, rather than NAHT shouting into a DfE-void, members’ concerns and NAHT’s recommendations were listened to by the DfE, which resulted in a letter from Robin Walker, minister for school standards, back in March.

In the letter, Robin confirmed that the DfE was now reviewing the materials to make them more user-friendly, simplifying the digital aspects to make them easier to navigate and access and streamlining the registration process.

On top of this, Robin pledged that the government remained committed to ensuring early career teachers and mentors had funded time set aside for the programme. “To support that, we’ve created new materials for school leaders, mentors and early career teachers to answer common questions about induction and ECF-based training,” he penned.

Crucially, he hinted that the government might be open to the idea of making the ECF more flexible generally, including around the use and funding of different providers.

As Robin wrote: “Some of the feedback we’ve received from mentors raises the question of how they can apply this structure flexibly to meet the particular needs of early career teachers.

“It is crucial that we maintain early career teachers’ entitlement to all of the high-quality content contained in these carefully sequenced programmes, but we also want mentors to be able to use their professional judgement in supporting early career teachers to understand and apply the content of the programmes to their particular contexts and their role. We will work with the lead providers and head teachers to produce guidance ahead of September so that mentors are clear on how they can do this."

As Ian points out, this win may not be a brake-skidding U-turn, but it is nevertheless important.

“We all want significant change, and sometimes the pace of change can feel frustrating. But incremental change like this is still significant. The DfE is very wedded to its particular views. This is an example of where we have aided it to understand that what it’s doing isn’t as helpful as it could be for early career teachers,” says Ian.

“What this shows is the participation of members. The emails they send us about what is going on in their schools, the frustrations they raise in branch and regional meetings and at national executive level, and the feedback they provide through our surveys – all of it matters; it really does make a difference.

“We have been able to take your views and, with your evidence, explain to officials and ministers where policy isn’t working well enough. By doing that, we have secured incremental change that will make members’ lives a bit better.

“The result of all of the lobbying, campaigning and survey work will be more flexibility in the ECF; there will be more opportunity for individuals to tailor their content better for their early career teachers, and we have secured a better understanding from the DfE that this should not be creating new workload for mentors or early career teachers.

“Crucially, we have convinced ministers that the ECF needs to be a supportive measure that isn’t creating extra workload. Even if it is incremental, it is still an important win. But we were only able to make this progress, make this step forward, because of what you, our members, told us,” Ian adds.

“We said the DfE needed to reduce the workload involved with the framework. It needed to stop the providers from setting evening and weekend work. We said things needed to be more flexible and that it was proving difficult to roll out given all the other pressures schools are under. We also called for the framework to be more about supporting teachers than forcing them to follow a curriculum and this notion of fidelity,” Ian explains.

Positively, rather than NAHT shouting into a DfE-void, members’ concerns and NAHT’s recommendations were listened to by the DfE, which resulted in a letter from Robin Walker, minister for school standards, back in March.

In the letter, Robin confirmed that the DfE was now reviewing the materials to make them more user-friendly, simplifying the digital aspects to make them easier to navigate and access and streamlining the registration process.

On top of this, Robin pledged that the government remained committed to ensuring early career teachers and mentors had funded time set aside for the programme. “To support that, we’ve created new materials for school leaders, mentors and early career teachers to answer common questions about induction and ECF-based training,” he penned.

Crucially, he hinted that the government might be open to the idea of making the ECF more flexible generally, including around the use and funding of different providers.

As Robin wrote: “Some of the feedback we’ve received from mentors raises the question of how they can apply this structure flexibly to meet the particular needs of early career teachers.

“It is crucial that we maintain early career teachers’ entitlement to all of the high-quality content contained in these carefully sequenced programmes, but we also want mentors to be able to use their professional judgement in supporting early career teachers to understand and apply the content of the programmes to their particular contexts and their role. We will work with the lead providers and head teachers to produce guidance ahead of September so that mentors are clear on how they can do this."

As Ian points out, this win may not be a brake-skidding U-turn, but it is nevertheless important.

“We all want significant change, and sometimes the pace of change can feel frustrating. But incremental change like this is still significant. The DfE is very wedded to its particular views. This is an example of where we have aided it to understand that what it’s doing isn’t as helpful as it could be for early career teachers,” says Ian.

“What this shows is the participation of members. The emails they send us about what is going on in their schools, the frustrations they raise in branch and regional meetings and at national executive level, and the feedback they provide through our surveys – all of it matters; it really does make a difference.

“We have been able to take your views and, with your evidence, explain to officials and ministers where policy isn’t working well enough. By doing that, we have secured incremental change that will make members’ lives a bit better.

“The result of all of the lobbying, campaigning and survey work will be more flexibility in the ECF; there will be more opportunity for individuals to tailor their content better for their early career teachers, and we have secured a better understanding from the DfE that this should not be creating new workload for mentors or early career teachers.

“Crucially, we have convinced ministers that the ECF needs to be a supportive measure that isn’t creating extra workload. Even if it is incremental, it is still an important win. But we were only able to make this progress, make this step forward, because of what you, our members, told us,” Ian adds.

"I HAD MY EARLY CAREER TEACHER IN TEARS HOLDING A RESIGNATION LETTER IN HER HAND".

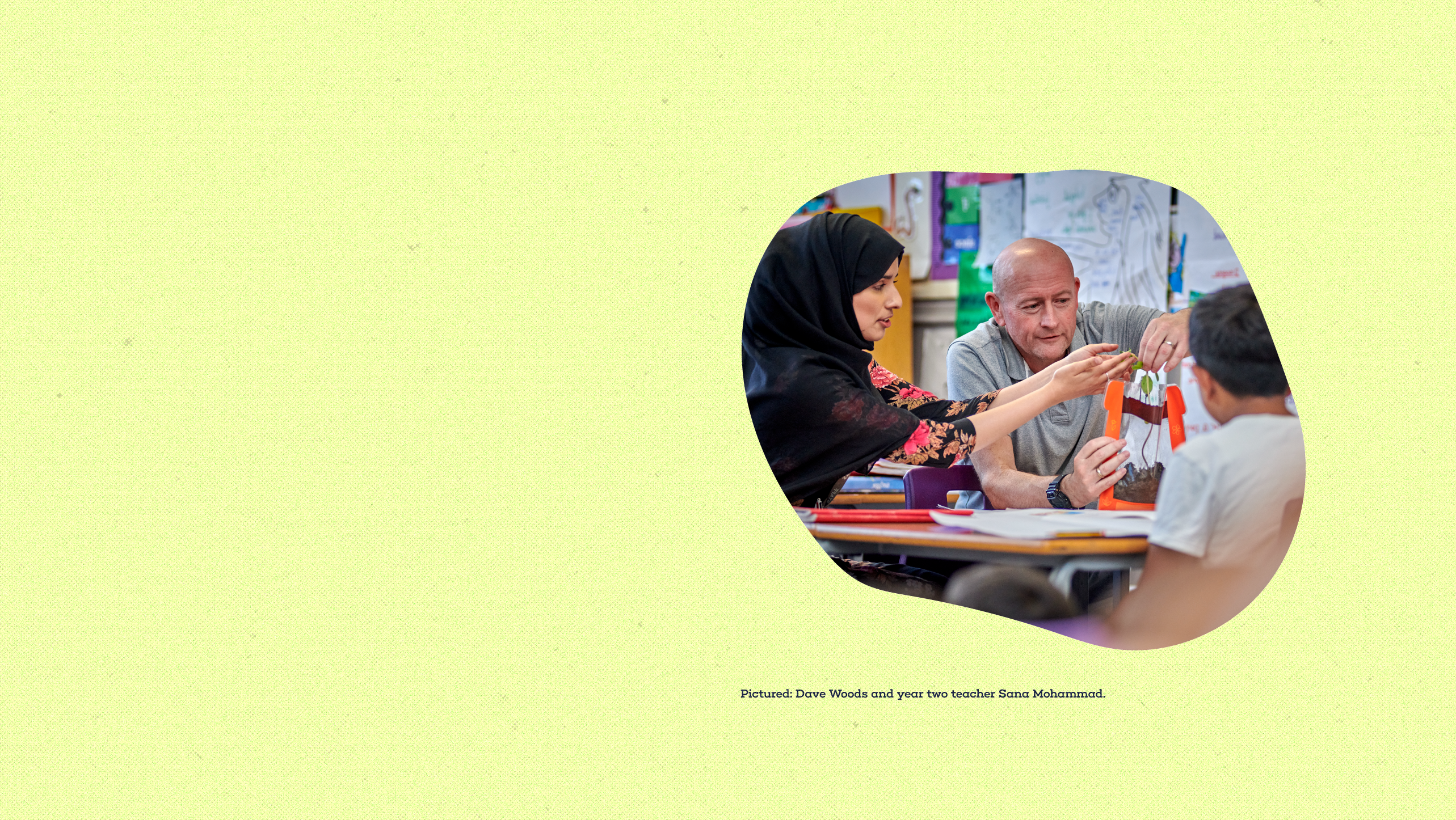

DAVE WOODS

HEAD TEACHER AT BEACONSFIELD PRIMARY SCHOOL IN SOUTHALL

Dave Woods, head teacher at Beaconsfield Primary School in Southall, vividly recalls when he realised the DfE’s ECF just wasn’t working for him or his school.

“I had my early career teacher in tears holding a resignation letter in her hand saying, ‘I can’t manage this; I can’t deal with this’. I had the mentor on my leadership team up in arms because of the workload,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“The real problem with it has been the rigidness of the programme, whether that is how the DfE intended it or whether it is down to the providers who have been selected to deliver it. There is a real disconnect with the way that schools work.

“The early career teacher and her mentor had to find fixed periods every week. You couldn’t move from one discussion/task to the next unless you did the previous task because it linked in with the online learning, and then there was the reflection time and the notetaking from the online learning that the early career teacher had to do. It was just the constant pressure aspect, and there was just no flexibility. It brought down the role of being an early career teacher to a tick-box mentality rather than what it really is: a long-term developing craft,” Dave says.

DAVE WOODS

HEAD TEACHER AT BEACONSFIELD PRIMARY SCHOOL IN SOUTHALL

Dave Woods, head teacher at Beaconsfield Primary School in Southall, vividly recalls when he realised the DfE’s ECF just wasn’t working for him or his school.

“I had my early career teacher in tears holding a resignation letter in her hand saying, ‘I can’t manage this; I can’t deal with this’. I had the mentor on my leadership team up in arms because of the workload,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“The real problem with it has been the rigidness of the programme, whether that is how the DfE intended it or whether it is down to the providers who have been selected to deliver it. There is a real disconnect with the way that schools work.

“The early career teacher and her mentor had to find fixed periods every week. You couldn’t move from one discussion/task to the next unless you did the previous task because it linked in with the online learning, and then there was the reflection time and the notetaking from the online learning that the early career teacher had to do. It was just the constant pressure aspect, and there was just no flexibility. It brought down the role of being an early career teacher to a tick-box mentality rather than what it really is: a long-term developing craft,” Dave says.

Beaconsfield Primary School now broadly follows the ECF, but it has adapted it to create more flexibility for the early career teacher and mentor. “We still follow the strands of the framework, so we’ve had to step up the structure of our programme, especially around what CPD we offer our early career teachers, what mentoring we have and so on.

“We’re still doing planned observations, still doing formal assessment and still writing a report to submit to the local authority for the quality assurance. We are following the framework, but we are following it in terms of being responsible for the delivery and CPD. This is more supportive of staff members’ well-being.

“The key difference is we’re making the decisions about the dates, times and flexibility. Unlike with the external provider, one week, it might be a Tuesday afternoon, and the following week it might be a Thursday morning because that’s the time that works for both. Moving from being a trainee into full-time, five-days-a-week teaching is a huge step for people, so early career teachers need that degree of flexibility.

“This allows the framework to work much better for the early career teacher and mentor and more simply for the whole school in terms of how we have to release other staff,” Dave adds.

Beaconsfield Primary School now broadly follows the ECF, but it has adapted it to create more flexibility for the early career teacher and mentor. “We still follow the strands of the framework, so we’ve had to step up the structure of our programme, especially around what CPD we offer our early career teachers, what mentoring we have and so on.

“We’re still doing planned observations, still doing formal assessment and still writing a report to submit to the local authority for the quality assurance. We are following the framework, but we are following it in terms of being responsible for the delivery and CPD. This is more supportive of staff members’ well-being.

“The key difference is we’re making the decisions about the dates, times and flexibility. Unlike with the external provider, one week, it might be a Tuesday afternoon, and the following week it might be a Thursday morning because that’s the time that works for both. Moving from being a trainee into full-time, five-days-a-week teaching is a huge step for people, so early career teachers need that degree of flexibility.

“This allows the framework to work much better for the early career teacher and mentor and more simply for the whole school in terms of how we have to release other staff,” Dave adds.

Separate from the ECF, new research has suggested that the most significant ethnic disparities in teachers’ career progression occur during early career stages, especially in postgraduate initial teacher training (ITT).

In partnership with education charities Ambition Institute and Teach First, the study from the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) has highlighted that applicants from white ethnic backgrounds have higher acceptance rates to ITT courses than every other ethnic group.

The quantitative 'Racial equality in the teacher workforce' research revealed that people from Asian, Black and other ethnic backgrounds are over-represented among applicants to postgraduate ITT, suggesting there is no lack of interest in entering teaching among these groups, said NFER.

However, compared with their white counterparts, acceptance rates to postgraduate ITT courses were nine percentage points lower for applicants from mixed ethnic backgrounds, 13 percentage points lower for applicants from Asian ethnic backgrounds and 21 percentage points lower for applicants from Black and other ethnic backgrounds.

The research also reveals substantial disparities in the progression of teachers from ethnic minority groups throughout the teacher career pipeline, resulting in significant under-representation at senior leadership and headship levels.

For example, middle leaders from Asian ethnic backgrounds were three percentage points less likely to be promoted to senior leadership than their white counterparts, and middle leaders from Black ethnic backgrounds were four percentage points less likely, the research argued.

Ethnic disparities in teacher retention rates were smaller in schools with diverse school leadership teams and larger in schools with all-white leadership teams, reinforcing the importance of how the actions of leaders and decision-makers are central to understanding why ethnic disparities exist within the system, it added.

Report co-author and NFER’s school workforce lead Jack Worth said: “The evidence in the report adds detailed and analytical insights into where ethnic disparities in progression within the teacher career pipeline are greatest, which will support the sector to make improvements and lasting changes in the areas where they are most needed.”

NATALIE ARNETT

NAHT SENIOR EQUALITIES OFFICER

Commenting on NFER’s study, Natalie said:

“There has been a welcome improvement in discussing the barriers people from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds face, including in education. But there is still much more work to be done. Research like this is important in facilitating this conversation further, helping us understand where the barriers are – though not why.

“We would encourage this research to be considered alongside qualitative research and lived experiences, such as our ‘You Are Not Alone: leaders for race equality’ book, which shares the personal experiences of 14 NAHT members from Asian, African, Caribbean and multiple backgrounds and their journey into leadership.

“NAHT is committed to playing its part, and alongside other key organisations working in the sector, we will shortly be releasing an updated ‘statement of action’, outlining our commitments to help further equality, diversity and inclusion in education.

“While a sector-wide approach is essential, if we are to see true progress in this area, this really must be matched by effective support from the government. If the DfE is serious about improving recruitment and retention of educational professionals from a diverse range of backgrounds, then it is vital that this is embedded across all facets of its work and backed by appropriate funding.”

Separate from the ECF, new research has suggested that the most significant ethnic disparities in teachers’ career progression occur during early career stages, especially in postgraduate initial teacher training (ITT).

In partnership with education charities Ambition Institute and Teach First, the study from the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) has highlighted that applicants from white ethnic backgrounds have higher acceptance rates to ITT courses than every other ethnic group.

The quantitative 'Racial equality in the teacher workforce' research revealed that people from Asian, Black and other ethnic backgrounds are over-represented among applicants to postgraduate ITT, suggesting there is no lack of interest in entering teaching among these groups, said NFER.

However, compared with their white counterparts, acceptance rates to postgraduate ITT courses were nine percentage points lower for applicants from mixed ethnic backgrounds, 13 percentage points lower for applicants from Asian ethnic backgrounds and 21 percentage points lower for applicants from Black and other ethnic backgrounds.

The research also reveals substantial disparities in the progression of teachers from ethnic minority groups throughout the teacher career pipeline, resulting in significant under-representation at senior leadership and headship levels.

For example, middle leaders from Asian ethnic backgrounds were three percentage points less likely to be promoted to senior leadership than their white counterparts, and middle leaders from Black ethnic backgrounds were four percentage points less likely, the research argued.

Ethnic disparities in teacher retention rates were smaller in schools with diverse school leadership teams and larger in schools with all-white leadership teams, reinforcing the importance of how the actions of leaders and decision-makers are central to understanding why ethnic disparities exist within the system, it added.

Report co-author and NFER’s school workforce lead Jack Worth said: “The evidence in the report adds detailed and analytical insights into where ethnic disparities in progression within the teacher career pipeline are greatest, which will support the sector to make improvements and lasting changes in the areas where they are most needed.”

NATALIE ARNETT

NAHT SENIOR EQUALITIES OFFICER

Commenting on NFER’s study, Natalie said:

“There has been a welcome improvement in discussing the barriers people from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds face, including in education. But there is still much more work to be done. Research like this is important in facilitating this conversation further, helping us understand where the barriers are – though not why.

“We would encourage this research to be considered alongside qualitative research and lived experiences, such as our ‘You Are Not Alone: leaders for race equality’ book, which shares the personal experiences of 14 NAHT members from Asian, African, Caribbean and multiple backgrounds and their journey into leadership.

“NAHT is committed to playing its part, and alongside other key organisations working in the sector, we will shortly be releasing an updated ‘statement of action’, outlining our commitments to help further equality, diversity and inclusion in education.

“While a sector-wide approach is essential, if we are to see true progress in this area, this really must be matched by effective support from the government. If the DfE is serious about improving recruitment and retention of educational professionals from a diverse range of backgrounds, then it is vital that this is embedded across all facets of its work and backed by appropriate funding.”