Leadership Focus journalist Nic Paton looks at the new book You Are Not Alone, which brings together 14 stories from members of NAHT’s Leaders for Race Equality group.

“This is monumental. This is historic. This is a pivotal moment in history.” So said Philonise Floyd in April in response to the conviction of US police officer Derek Chauvin for the murder of his brother George Floyd in May last year.

George Floyd’s murder – harrowingly caught on camera – marked a watershed moment in US race relations, sparking a wave of protests and acting as a rocket booster to the Black Lives Matter movement, which had itself emerged in the wake of the death of African-American teenager Trayvon Martin six years previously.

LORNA LEGG, HEAD TEACHER OF OFFWELL CHURCH OF ENGLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL IN HONITON, DEVON

Floyd’s death, the weeks of turmoil that followed, the ‘I can’t breathe’ slogan of Black Lives Matter and then, finally, the conviction of Chauvin; these all resonated with many people around the world, especially those from Black, Asian or minority ethnic backgrounds, recalls Lorna Legg, head teacher of Offwell Church of England Primary School in Honiton, Devon.

“That was a pivotal point for lots of people from diverse backgrounds, but particularly for those with African and Caribbean backgrounds, where skin colour alone can make you a target. It was even more shocking because it was on camera, and it reflects the real fears of many in the UK, including nurses, barristers, MPs and sports personalities, who have recently experienced ‘stop and search’ and even arrest while simply going about their lives,” she tells Leadership Focus.

“It, I think, spurred lots of people into looking for ways to respond to that horror,” she adds.

As Leadership Focus reported last autumn, the energising effect of that summer saw the creation of a new member-led NAHT group, Leaders for Race Equality, which was designed to give a voice to NAHT’s Black, Asian and minority ethnic members and inform and deepen the knowledge and expertise of all members when it comes to race, diversity and inclusion.

While a relatively informal group, its meetings have already made an immediate impact, both for members of the group themselves and the wider NAHT community.

“People’s experiences throughout their education came out; it wasn’t just us as leaders.

“And we felt they should be out there in the public domain.”

“This is monumental. This is historic. This is a pivotal moment in history.” So said Philonise Floyd in April in response to the conviction of US police officer Derek Chauvin for the murder of his brother George Floyd in May last year.

George Floyd’s murder – harrowingly caught on camera – marked a watershed moment in US race relations, sparking a wave of protests and acting as a rocket booster to the Black Lives Matter movement, which had itself emerged in the wake of the death of African-American teenager Trayvon Martin six years previously.

LORNA LEGG, HEAD TEACHER OF OFFWELL CHURCH OF ENGLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL IN HONITON, DEVON

Floyd’s death, the weeks of turmoil that followed, the ‘I can’t breathe’ slogan of Black Lives Matter and then, finally, the conviction of Chauvin; these all resonated with many people around the world, especially those from Black, Asian or minority ethnic backgrounds, recalls Lorna Legg, head teacher of Offwell Church of England Primary School in Honiton, Devon.

“That was a pivotal point for lots of people from diverse backgrounds, but particularly for those with African and Caribbean backgrounds, where skin colour alone can make you a target. It was even more shocking because it was on camera, and it reflects the real fears of many in the UK, including nurses, barristers, MPs and sports personalities, who have recently experienced ‘stop and search’ and even arrest while simply going about their lives,” she tells Leadership Focus.

“It, I think, spurred lots of people into looking for ways to respond to that horror,” she adds.

As Leadership Focus reported last autumn, the energising effect of that summer saw the creation of a new member-led NAHT group, Leaders for Race Equality, which was designed to give a voice to NAHT’s Black, Asian and minority ethnic members and inform and deepen the knowledge and expertise of all members when it comes to race, diversity and inclusion.

While a relatively informal group, its meetings have already made an immediate impact, both for members of the group themselves and the wider NAHT community.

“People’s experiences throughout their education came out; it wasn’t just us as leaders.

“And we felt they should be out there in the public domain.”

That impetus, in turn, led to the publication last month [June] of You Are Not Alone, a collection of personal stories and experiences from 14 members of the group, including Lorna. It has been published as a limited-edition print publication and, more widely, as an e-book for dissemination to NAHT members and schools themselves.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

As NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman puts it: “We have ambitious plans for this book. We’re not, of course, making a profit out of this. We have a number of hard copies that we’re going to distribute carefully for impact. But then we’re going to make it widely available in electronic format.

“We plan to get an electronic link to the book in every school and then build from there. We are also talking to the Department for Education about how to get it into teacher training colleges. We believe it is so inspiring that it has a place there in encouraging people to move forward,” he adds.

The 14 stories (see our extracts below) contain very personal accounts of the casual, day-to-day racism and barriers many NAHT members have experienced in their lives, both as children in the school environment and as teachers and leaders. It is also a clarion call to arms for the profession to get better, be better and be more inclusive and transparent around race, diversity and inclusion.

As Paul argues passionately: “At NAHT, we do have to be brave enough to look to ourselves. We are a reflection of school leadership in itself, and therefore, we need to make sure that, in everything we do that promotes the profession, we solve our own difficulties as much as everything else.

“As a well-meaning, white man – and, after all, I even happen to be called ‘Whiteman’ – I sometimes struggle to find the right words. I know my reactions to equality are the right reactions. But how do I make sure NAHT articulates the pain and frustrations of our members from the Black community? How do we do that as a union that is still broadly white in its membership?

“It is their stories, and I am really proud of the collection we have put together,” Paul adds.

Further to raising awareness of the barriers and challenges, however, is the hope the book can provide positive impetus too; that it can act as an inspiration to school children from minority ethnic backgrounds as well as classroom teachers and would-be leaders.

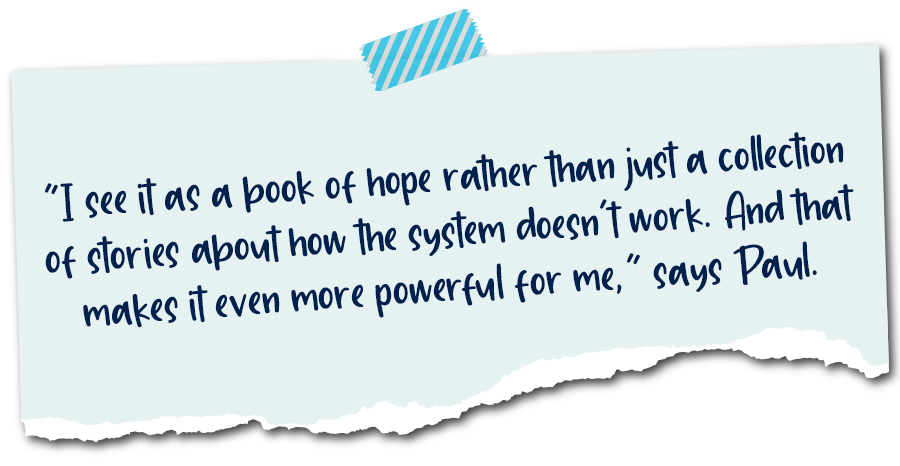

“What hits me is just how inspiring and full of hope the stories are,” Paul emphasises. “One of my expectations was that I would be reading examples of racism, examples of where people hadn’t been given the opportunity or the equality of outcome that we are all striving for, and it would just reinforce our knowledge of the problem.

“But, alongside this, the value of role models and role modelling,” agrees Lorna. “We are all school leaders at different levels, but only a small percentage of school leaders are from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups.

“It is important to see that there have been difficulties, there have been barriers, yet we have still got to these positions.

“The other thing is to be able to walk in somebody else’s shoes and possibly recognise, ‘oh, you know what, I think I might have done that myself without realising how that might feel’.

“We are all subject to unconscious bias; it’s how our brains work at the most basic level. It is also formed out of the narrative we have grown up with, from our history books to some of our media. But we know people cannot be categorised into simple groups, and no person should ever be reduced to a set of assumptions based purely on their appearance.

“We need to be aware of some of the stereotypes we all hold and challenge some of our responses, realising the impact of some of those things – looks, names or comments – and how they impact on people, especially children. Sometimes, it’s the small things, like always getting someone’s name wrong in the register, or asking ‘where are you from?’ when you were born here, that people might not have thought how alienating that might feel,” Lorna adds.

“There is a general agreement that we, as a union, have not been successful enough; we’re not moving fast enough to change things. There is an appetite among people to look at the fundamental causes that sit behind this and change those too,” argues Paul in conclusion.

“So, I think our job is to grab those moments in history, such as the tragic murder of George Floyd, and make as much progress as we possibly can. Hopefully, You Are Not Alone can be one small part within that,” he adds.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

As NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman puts it: “We have ambitious plans for this book. We’re not, of course, making a profit out of this. We have a number of hard copies that we’re going to distribute carefully for impact. But then we’re going to make it widely available in electronic format.

“We plan to get an electronic link to the book in every school and then build from there. We are also talking to the Department for Education about how to get it into teacher training colleges. We believe it is so inspiring that it has a place there in encouraging people to move forward,” he adds.

The 14 stories (see our extracts below) contain very personal accounts of the casual, day-to-day racism and barriers many NAHT members have experienced in their lives, both as children in the school environment and as teachers and leaders. It is also a clarion call to arms for the profession to get better, be better and be more inclusive and transparent around race, diversity and inclusion.

As Paul argues passionately: “At NAHT, we do have to be brave enough to look to ourselves. We are a reflection of school leadership in itself, and therefore, we need to make sure that, in everything we do that promotes the profession, we solve our own difficulties as much as everything else.

“As a well-meaning, white man – and, after all, I even happen to be called ‘Whiteman’ – I sometimes struggle to find the right words. I know my reactions to equality are the right reactions. But how do I make sure NAHT articulates the pain and frustrations of our members from the Black community? How do we do that as a union that is still broadly white in its membership?

“It is their stories, and I am really proud of the collection we have put together,” Paul adds.

Further to raising awareness of the barriers and challenges, however, is the hope the book can provide positive impetus too; that it can act as an inspiration to school children from minority ethnic backgrounds as well as classroom teachers and would-be leaders.

“What hits me is just how inspiring and full of hope the stories are,” Paul emphasises. “One of my expectations was that I would be reading examples of racism, examples of where people hadn’t been given the opportunity or the equality of outcome that we are all striving for, and it would just reinforce our knowledge of the problem.

“But, alongside this, the value of role models and role modelling,” agrees Lorna. “We are all school leaders at different levels, but only a small percentage of school leaders are from Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups.

“It is important to see that there have been difficulties, there have been barriers, yet we have still got to these positions.

“The other thing is to be able to walk in somebody else’s shoes and possibly recognise, ‘oh, you know what, I think I might have done that myself without realising how that might feel’.

“We are all subject to unconscious bias; it’s how our brains work at the most basic level. It is also formed out of the narrative we have grown up with, from our history books to some of our media. But we know people cannot be categorised into simple groups, and no person should ever be reduced to a set of assumptions based purely on their appearance.

“We need to be aware of some of the stereotypes we all hold and challenge some of our responses, realising the impact of some of those things – looks, names or comments – and how they impact on people, especially children. Sometimes, it’s the small things, like always getting someone’s name wrong in the register, or asking ‘where are you from?’ when you were born here, that people might not have thought how alienating that might feel,” Lorna adds.

“There is a general agreement that we, as a union, have not been successful enough; we’re not moving fast enough to change things. There is an appetite among people to look at the fundamental causes that sit behind this and change those too,” argues Paul in conclusion.

“So, I think our job is to grab those moments in history, such as the tragic murder of George Floyd, and make as much progress as we possibly can. Hopefully, You Are Not Alone can be one small part within that,” he adds.

You Are Not Alone brings together 14 stories from members of NAHT’s Leaders for Race Equality group. Here are extracts from five of them.

AMA OSAPANIN,

ASSISTANT HEAD TEACHER, CENTRAL LONDON

I remember, at school, writing a recount for a piece of literacy homework. It was a simple enough task. I wrote about my weekend. A weekend that I had spent with family. I wrote about what we watched on the television, the songs that we sang at the top of our lungs as my older cousin played an accompaniment on the piano and the food that we cooked and ate.

My aunt taught me how to make hand-rolled noodles that weekend. We had a great time. A weekend I was happy and proud to be writing about. I was so motivated by this piece of work.

Well, until my teacher marked it and gave it back to me. The gist of the feedback was that my recount didn’t sound very realistic and that people didn’t hand-roll noodles. What? Erm, it was a completely accurate recount – thank you very much. And yes, in the Filipino village that my mother and aunt grew up in, people, sometimes, hand-rolled noodles. Skilfully too!

It was a tradition that I loved learning and happily wrote about! But somehow, perhaps, it was too different an experience to be valued. Or, maybe, just too flamboyant for the assumptions that teacher had of me? Who knows?

My teacher told me that “over here” people “don’t do that”. What? People don’t spend time with their families!? Of course they do! Were my family strange for being ‘different’ in the way that they spent that time? Were our weekend activities not good enough? Why wasn’t I told that it sounded like a lovely weekend? That’s what I wanted to hear.

I really didn’t like how that felt. I was deflated. A little embarrassed too. Those questions. That doubt. It taught me to be less forthcoming about my experiences. I was a child, so I don’t want to blame myself for not making a fuss at the time. But goodness me, now, as an adult and a teacher, I’d hate to think that children are still exposed to such ignorance.

DIANA OHENE-DARKO,

ASSISTANT HEAD TEACHER, HARROW

While still training, I was given class responsibility, which was unheard of at the time. It felt as though my innate dynamism as a teacher and passion for education had been understood from the outset by leaders already in the field. I took great pride in setting up my classroom and organising tables, a seating plan, my desk and personal items.

Before long, I was in the swing of the weekly timetable and teaching all subjects while finishing my course. At first, the regular pop-ins/observations/in class sessions didn’t seem too untoward. I had to have weekly observations anyway as part of the course. It wasn’t until a table was set up in an unused classroom opposite, where two teachers had ‘set up shop’ so to speak, that I began to feel very uneasy, targeted even.

They remained there for a full term, which was the duration of my course. Neither teacher was in class; they took groups every now and then, but other than that, I’m not sure what they did other than observe my every move. I continued with a profound enthusiasm for the children I had in front of me. Nothing gave me greater pleasure than those light-bulb moments in which children ‘got it’. I even took the liberty of recreating Jane Elliott’s ‘Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes’ experiment as part of a discrimination lesson in RE. I was creative, confident and always maintained a positive outlook. Perhaps that’s what got to them.

I passed my course with flying colours and went on to complete my newly qualified teacher year, again in year six, before completing a year in year four. I built up my teaching experience (and courage) before moving on to my first leadership position for a curriculum area, with oversight over the whole curriculum.

I want to be part of the next generation of leaders. Leaders who have equality on the agenda. Leaders who ‘see’ everyone and are bold enough to make changes. I want to be that change. I want to make a difference. I want to leave a small part of the world better than I found it.

To those entering the profession or seeking leadership: go confidently into your future. Be bold, be brave and be you. Who you are will make the difference.

ELAINE WILLIAMS,

HEAD TEACHER, WEST MIDLANDS

I was told by white parents that I was racist. I was “all for the Black children”, and I “don’t care about the white ones”. They said that I gave the Black children preferential treatment, and I was unfairly hard on the white children. I was accused of racism by the Black parents. They said that I “didn’t understand Black children” and that I had “sold out” because I only cared about the white children.

They said I was “too hard” on the Black children. No win. As a leader, you take each situation and manage each one within the policies and procedures you have in place. It’s never about colour, but that was a battle I just couldn’t win.

Some staff were great and really kept me going. Others, they didn’t want me there. They would do anything to see me fail and try anything to make me leave – dark days.

I can remember one member of staff contacting the police in order to tell them that I was allowing weed onto the premises. Yep, she wanted to damage my reputation and career that much. Obviously, there was no truth in it, and nothing happened as a result of this, but someone said that about me when I’m sure they wouldn’t have said it about a white head teacher.

Another member of staff, who clearly thought it was time for me to move on, found and showed me new head teacher positions. Who does this for their head teacher? She obviously didn’t want to risk coming across me again as all the posts were international; in fact, they were in the Caribbean. I’m guessing that wouldn’t have happened to a white head teacher.

ROSS ASHCROFT,

HEAD TEACHER, BIRMINGHAM

I really noticed being treated differently in secondary school. For whatever reason, many teachers just did not have any real expectations of me succeeding in life. Granted, I wasn’t the best behaved, but I achieved well academically. I remember being sent out of the room during science for talking.

Now, most pupils protest their innocence, and this was no different, apart from the fact I was not actually talking. It was my friend in the row behind. He wanted to be sent out and even admitted aloud to the teacher that it was, in fact, him who was talking and not me. The teacher was uninterested in his confession and sent me out anyway.

When I came back in, after 30 minutes, she berated me in front of the class. I calmly explained that it was not me talking and reminded her that the boy behind me confessed that it was him.

“One day, I’m going to be a teacher, and I will make sure no one I teach will be treated the way I’m being treated now,” I said. “You will be lucky if you even get into college, never mind become a teacher,” she replied.

That struck me like a lightning bolt. Why would she say that? I was top set in English, maths and science. What would stop me from becoming a teacher? As I said earlier, I don’t see myself as a victim, so that lightning bolt charged me like nothing ever had done before.

It stayed present in my mind through every challenge; it propelled me forward, determined to become a teacher.

SYMONE CAMPBELL,

SCHOOL BUSINESS MANAGER, SURREY

When I started in my first (non-educational) managerial position as a young, naive 21-year-old, initially, my leadership was met with resistance. I rapidly discovered that when people think of leadership, a young Black woman is not the first picture that springs to mind.

After a while, I became accustomed to the fact that I wasn’t what people expected, but I used this as fuel to motivate me, which made me more determined to progress. Although I found it difficult not to take it personally, I would remind myself of the phrase ‘positive mental attitude’, which was my manager’s favourite saying.

Although there were no people of colour who were senior managers in the whole organisation, I was fortunate enough to experience the power of mentorship from three senior managers at different stages of my career, which I found to be effective in helping me to achieve my potential at work.

Despite these positive experiences, I still had to battle with prejudices. The typical micro-aggressions: the assumption that every Black employee has to be the junior member of staff, that I must be less qualified despite my credentials, questions about work ethic or performance, passion being misinterpreted as aggression and, occasionally, feeling misunderstood.

Colleagues with whom I had established working relationships over the telephone and then eventually met in person would look shocked to discover they had been speaking to a young Black woman. On the first occasion, I was quite offended, but then I learnt to enjoy exceeding people’s expectations of me.

I recall one day arriving at work wearing my natural hair, and a colleague stretched out her arm and attempted to touch my hair, but I recoiled with disgust, feeling shocked and angry that an attempt was made to stroke my hair like a pet. I thought to myself, why would you want to stroke my hair?

When I wore my hair straightened, there was never an interest to stroke it then. In hindsight, if this incident were to happen again, I would educate my colleague on why this would be considered inappropriate.

I would experience unconscious bias, comments such as “you would like this top”, and I would question “why is that?” and my colleague responded, “because it is African.”

Although some of these examples or comments may have been unintentionally offensive, the key point is we all have biases, and although unintentional, one should reflect on how the recipient perceives the offence. It is very similar to challenging the perception that children have of bullying. There is a stereotype of what racism is, but unfortunately, if you do not understand the different degrees or levels of racism, it may not be recognised as racism.

It is imperative to have diverse leaders and governors in school leadership, running our schools, to improve the awareness of different races, cultures, religions and economic status, ensuring they understand and can identify with the experiences of their whole school community and, more importantly, having open and honest discussions.

There is a need for more accountability, for people to be advocates for change, and to enhance and develop systems to improve the way diversity, inclusion and equality are managed, working towards eradicating systemic racism in the workplace. School improvement and strategic planning, reviewing recruitment processes – including having diverse interview panels, talent pipelines, training and ethnicity pay reporting – and other actions such as having the intention to work with a more diverse range of suppliers, all form part of the way forward.

On reflection now, as a Black school business leader, my personal and professional experiences, both good and bad, have helped to increase my awareness of how my behaviours can affect my work environment: leading by example, being mindful of the language I use, the tone I set with my own team and challenging inappropriate behaviour. Undoubtedly, we all have some self-reflection to undertake on things we can do better and ways we can positively contribute to change.

I am committing myself to be a part of the solution; if you have the same desire, I urge you now is the time to act.