Ofsted’s flawed approach

“Ofsted appears to have missed the point entirely about what makes these types of inspections and gradings damaging and harmful to school leaders.” – NAHT member

Ofsted’s flawed approach

“Ofsted appears to have missed the point entirely about what makes these types of inspections and gradings damaging and harmful to school leaders.” – NAHT member

Journalist Nic Paton takes a closer look at Ofsted’s consultation on its proposed new inspection model and how our members have received it.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

Pretty much around this time last year, NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman gave Ofsted’s initial moves in response to the tragedy of head teacher Ruth Perry’s death – pausing inspection and implementing training for inspectors – a cautious welcome, calling them “the first positive steps we have seen”.

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

Last summer, when Leadership Focus spoke to NAHT assistant general secretary James Bowen, he was clear that while these early reforms were helpful, what happened next would be crucial and that long-term reform needed to be about much more than just tinkering around the edges. Other early changes, such as schools only receiving the notice call on a Monday, landed well with school leaders.

The early move by education secretary Bridget Phillipson last autumn to scrap single-word judgements for schools in England was welcomed by NAHT as a step in the right direction.

Therefore, the fact that there has been an almost audible throwing up of hands in frustration at Ofsted’s consultation on its proposed new inspection model, announced in February, speaks volumes – and not in a good way.

Ofsted’s proposed inspection model and concerns

Ofsted’s proposed reforms face criticism for being outdated and inadequate.

Ofsted’s proposals are symptomatic of “an inspectorate determined to hold on to a model of inspection that is long past its sell-by date”, says Paul in response.

“We have real concerns,” agrees James. “It is clear that Ofsted has failed to grasp the level of reform that school leaders are expecting or looking for.”

In its consultation document, ‘Improving the way Ofsted inspects education’, Ofsted has outlined plans for a new inspection ‘report card’. The single-word judgement, it has proposed, will be replaced by a new five-point grading scale for each evaluation area, ranging from ‘causing concern’ to ‘attention needed’, ‘secure’, ‘strong’ and finally ‘exemplary’.

There will be a focus on returning to schools with identified weaknesses to check that “timely action” is being taken to raise standards, Ofsted said. There will be an increased focus on support for disadvantaged and vulnerable children and learners, including those with special educational needs and disabilities and more emphasis on providers’ circumstances and local context.

SIR MARTYN OLIVER,

CHIEF INSPECTOR

“The report card will replace the simplistic overall judgement with a suite of grades, giving parents much more detail and better identifying the strengths and areas for improvement for a school, early years or further education provider,” said Ofsted’s chief inspector Sir Martyn Oliver.

“Our new top ‘exemplary’ grade will help raise standards, identifying world-class practice that should be shared with the rest of the country. And by quickly returning to monitor schools that have areas for improvement, we will ensure timely action is taken to raise standards,” he added.

Reaction

from NAHT and school leaders

NAHT expresses concern over Ofsted’s consultation, highlighting the need for deeper reform and greater trust in the process.

For NAHT, however, this consultation – and, more widely, the whole process and, indeed, the pace of reform – is deeply problematic.

First, it simply does not recognise the scale of appetite for change within the profession – and the ongoing, lingering anger many feel at how little has changed two years on from Ruth Perry’s death.

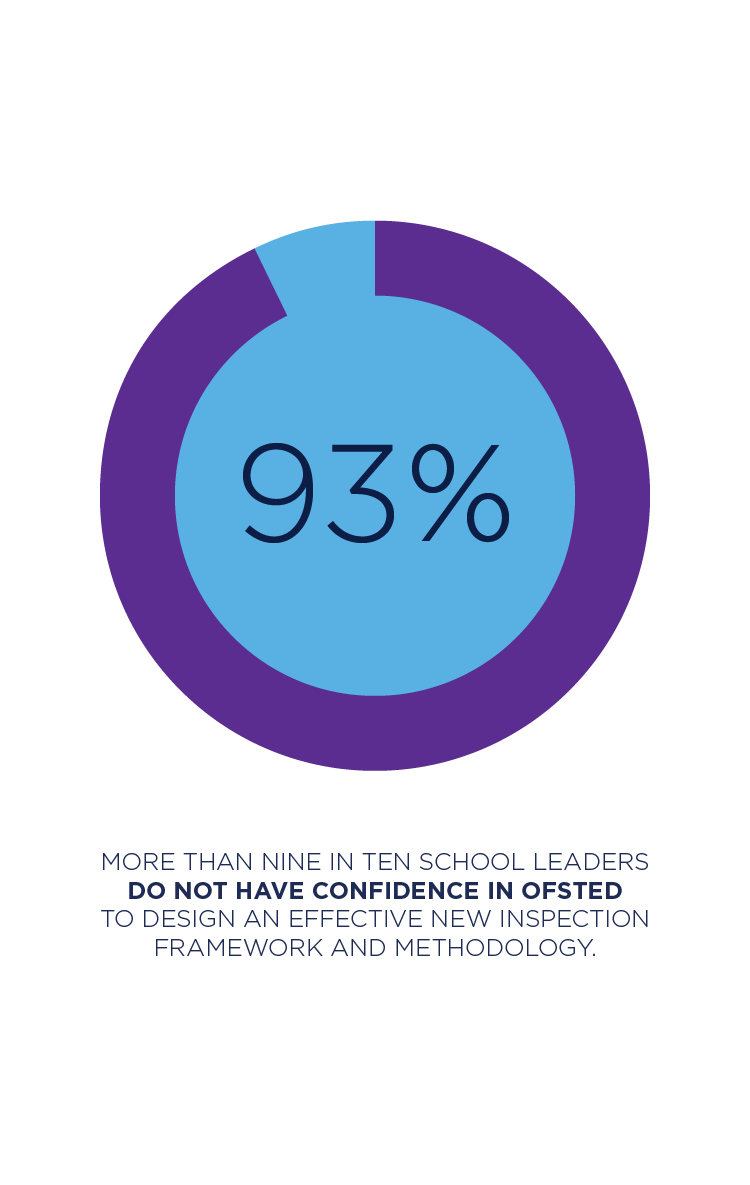

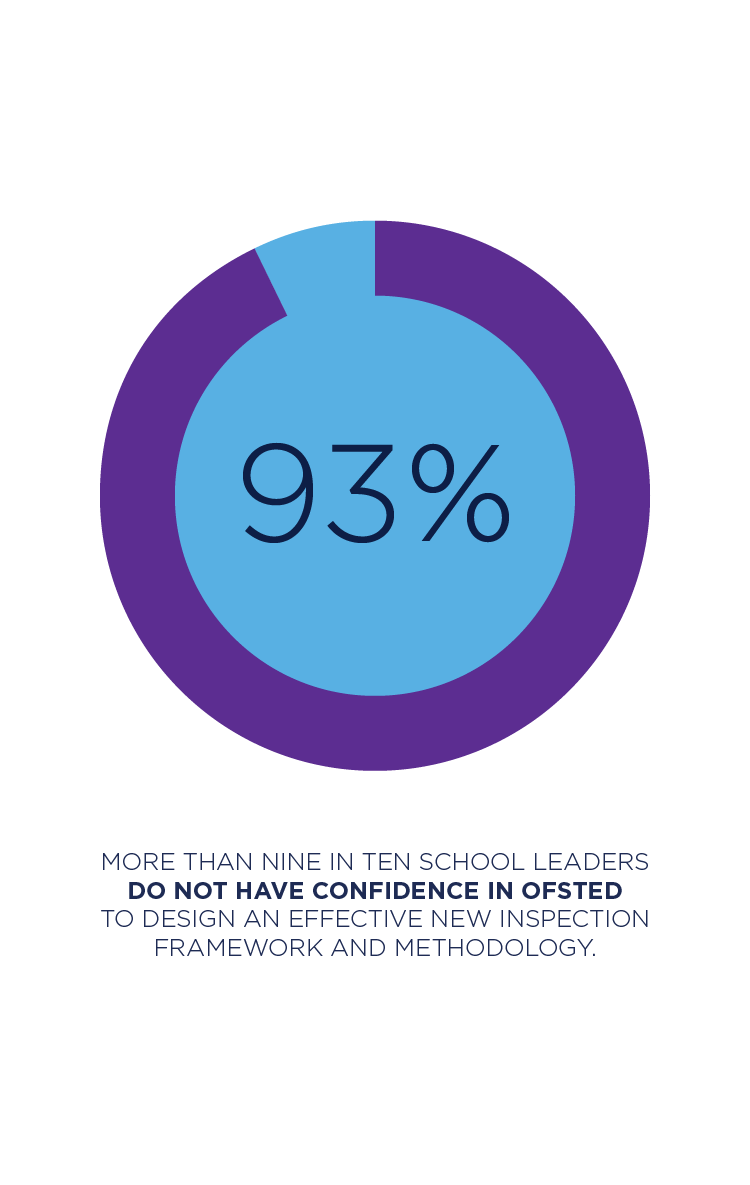

Indeed, NAHT research published just a few weeks before the consultation document emphasised the scale of distrust and scepticism towards Ofsted among school leaders. More than nine in ten school leaders (93%) did not have confidence in Ofsted to design an effective new inspection framework.

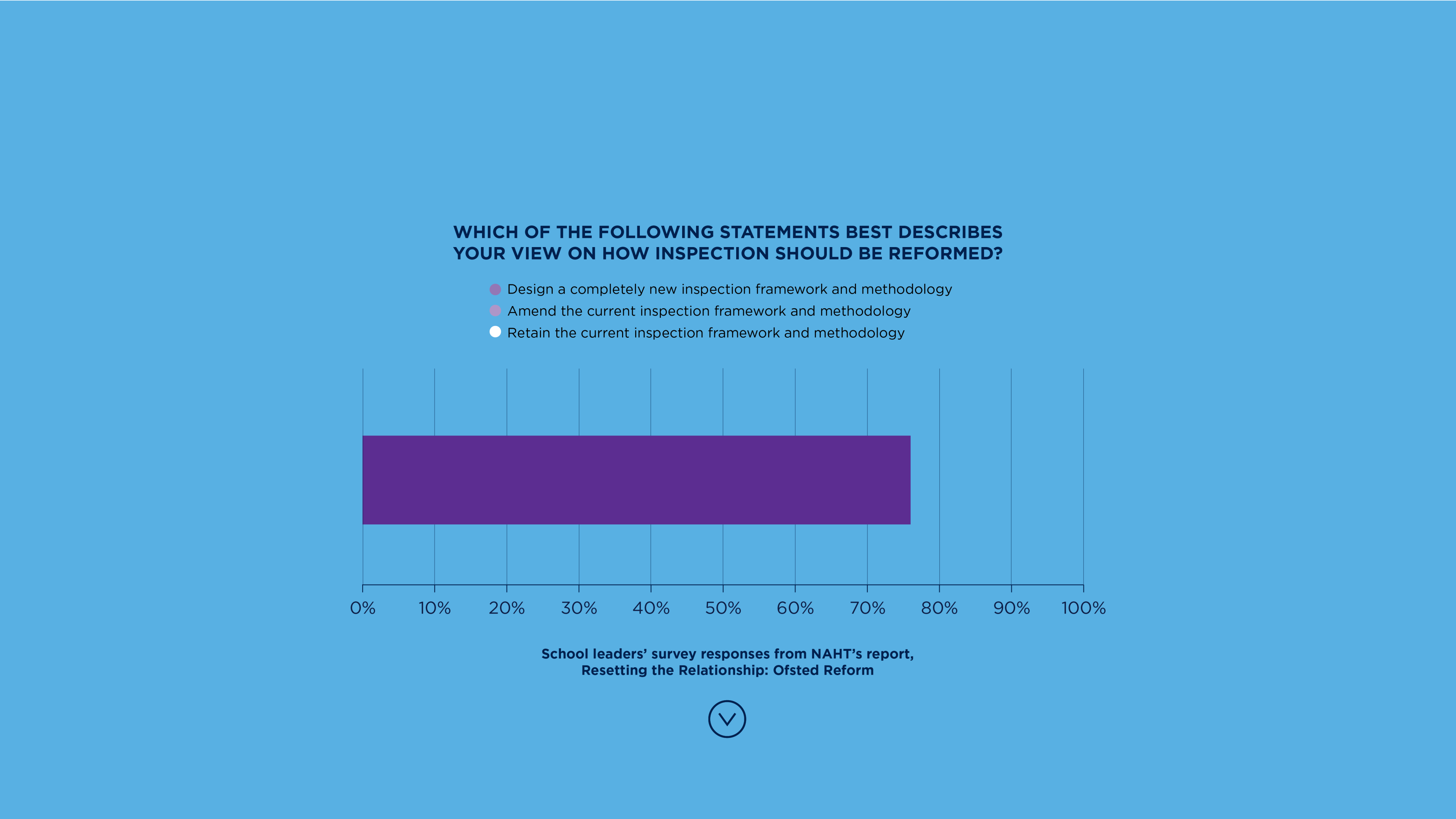

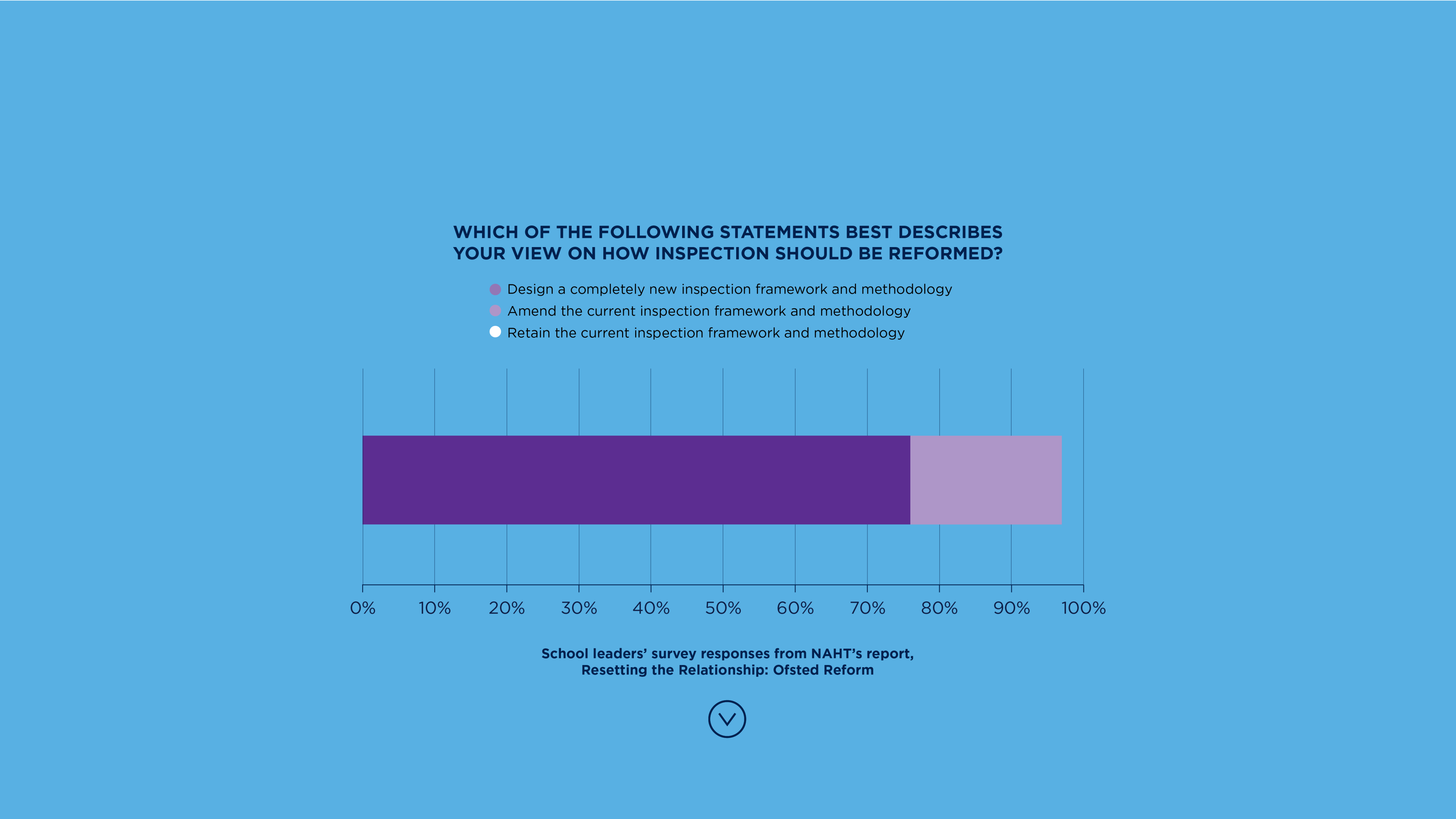

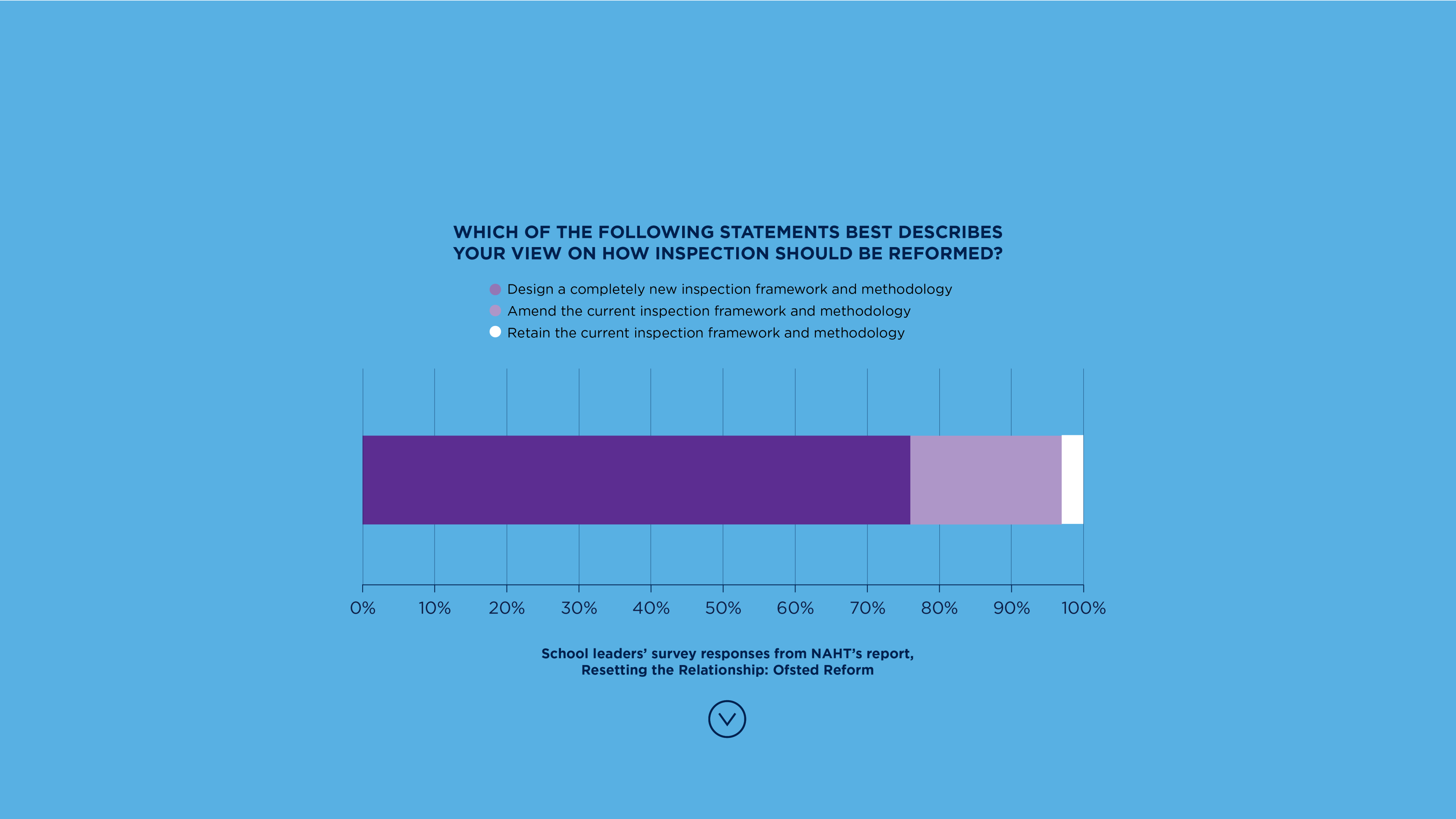

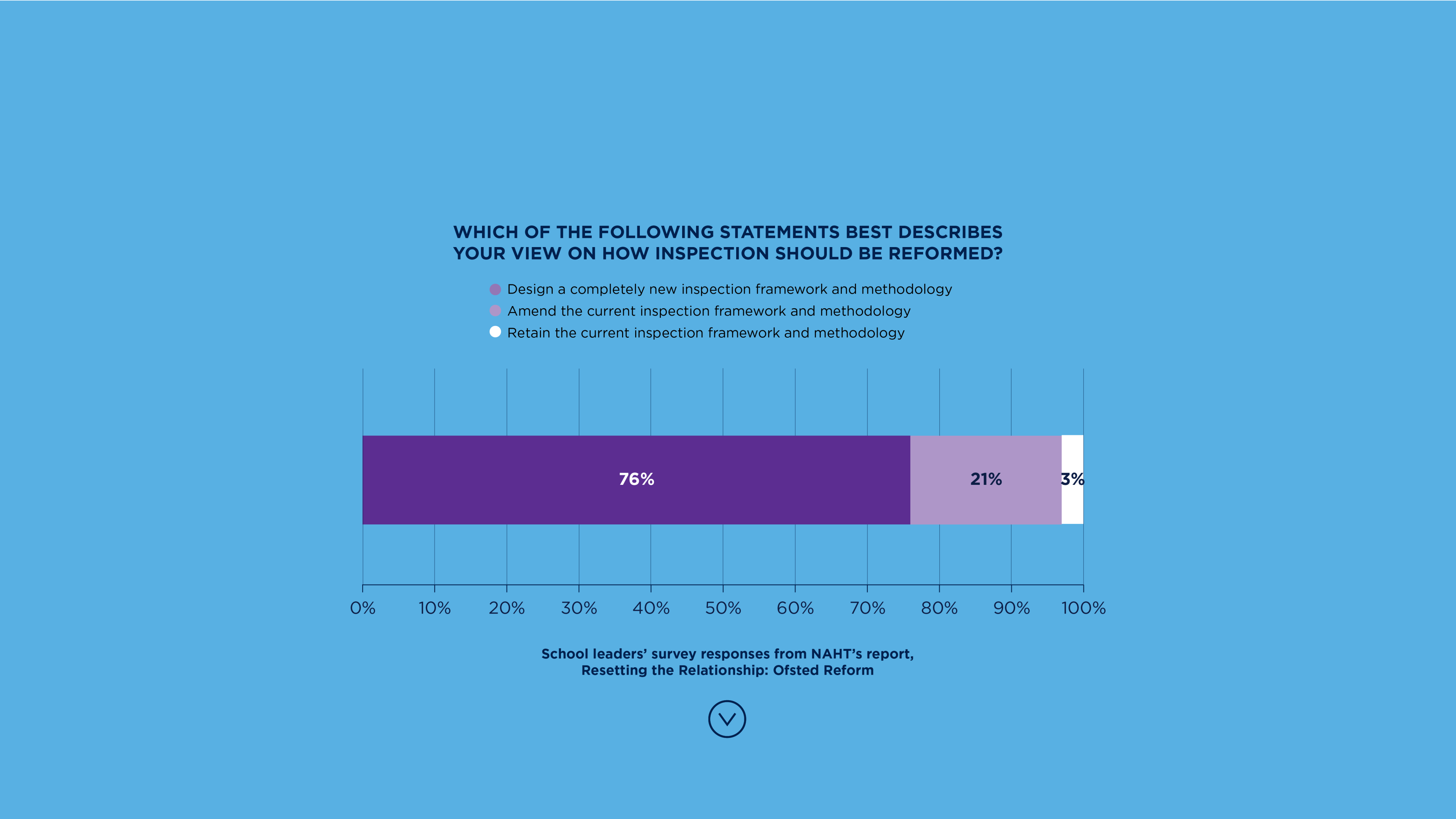

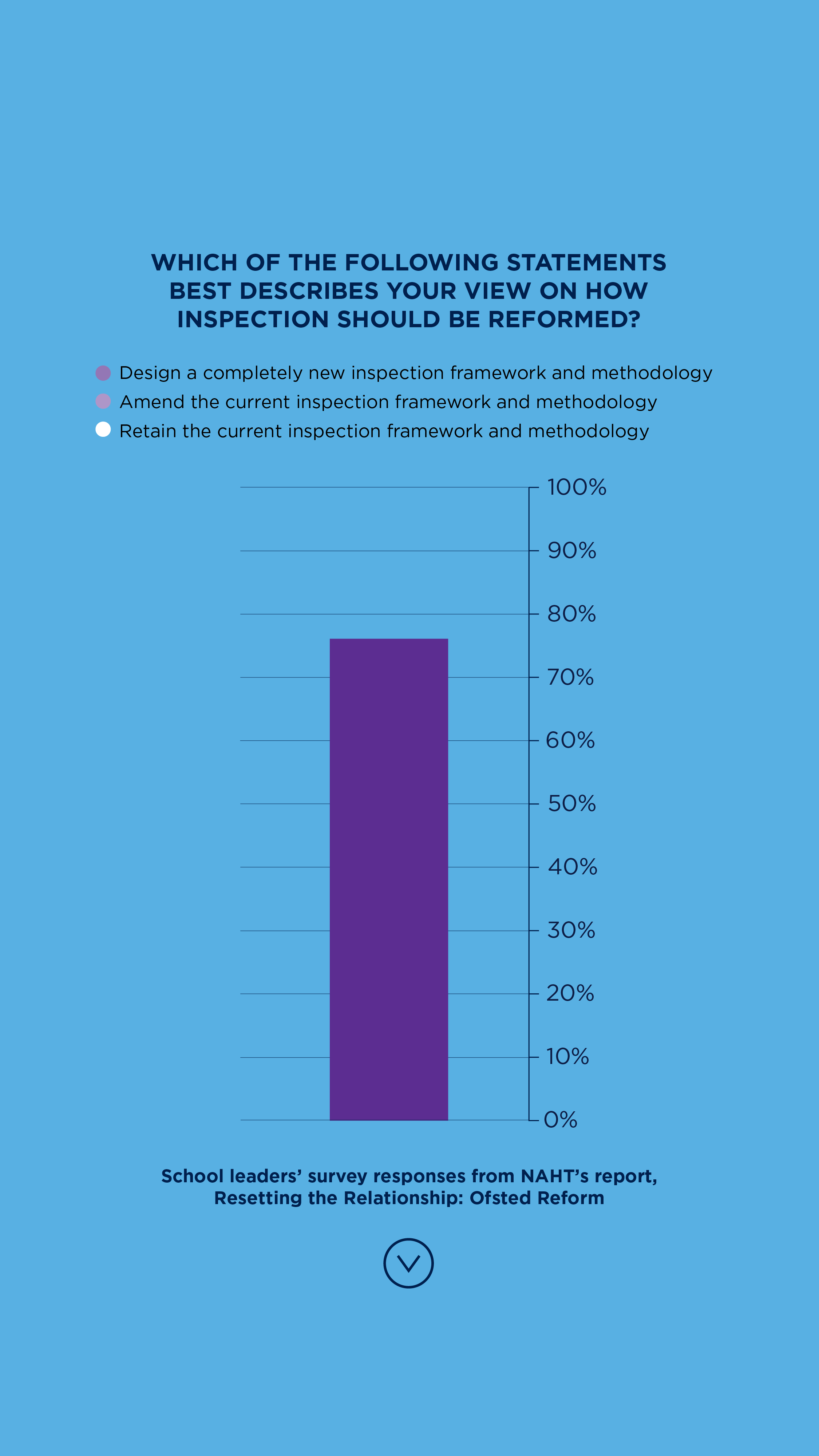

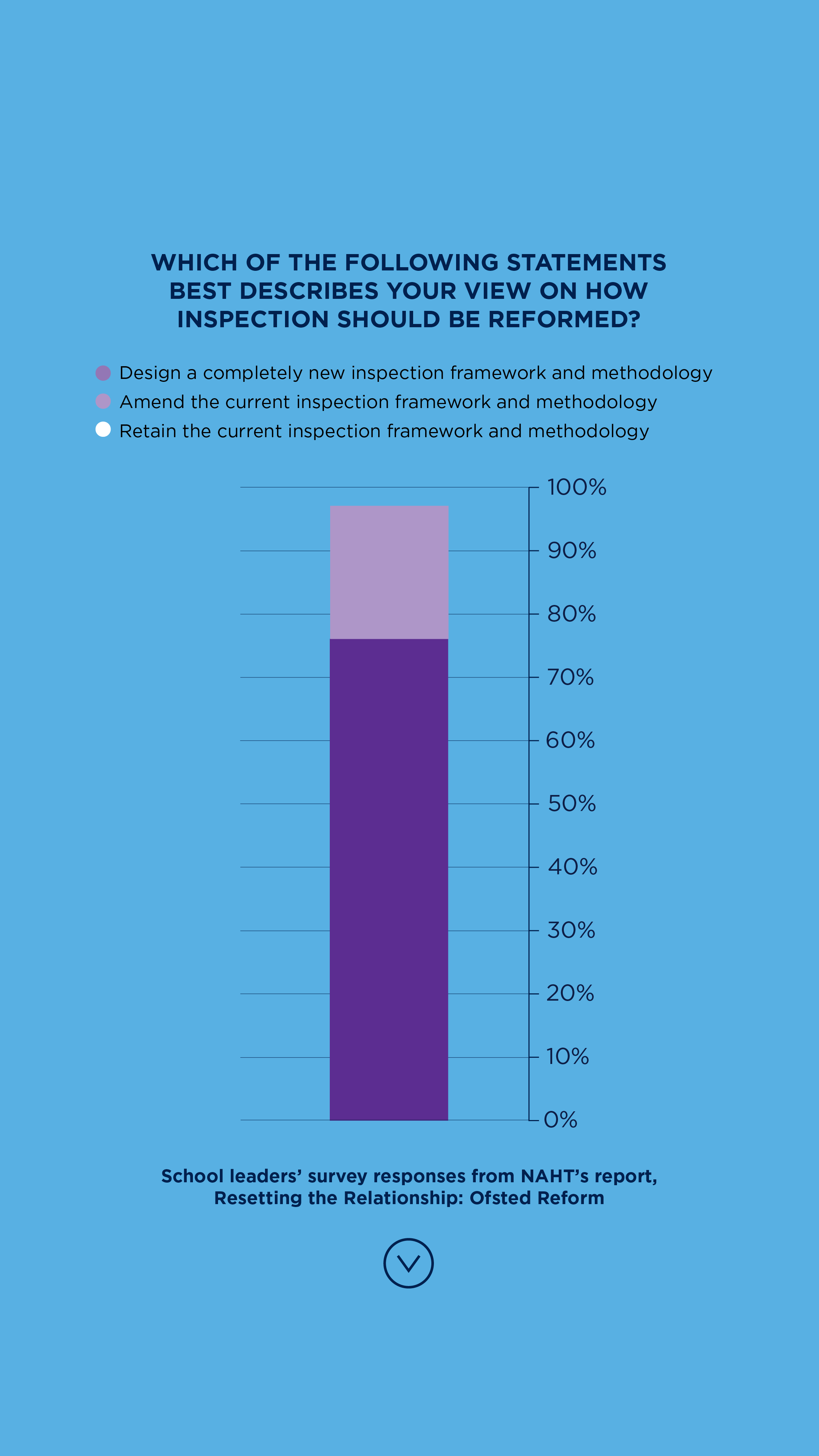

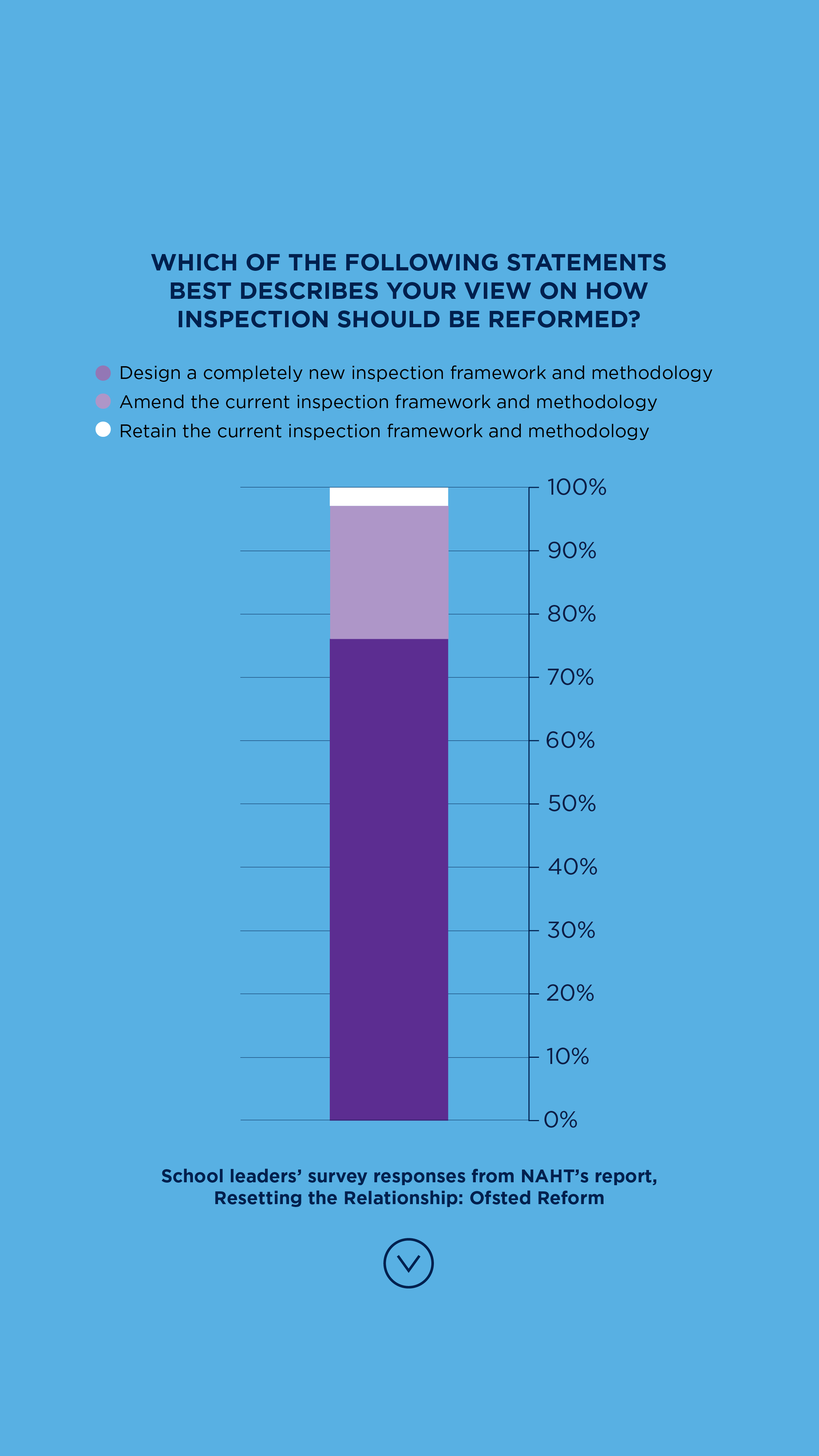

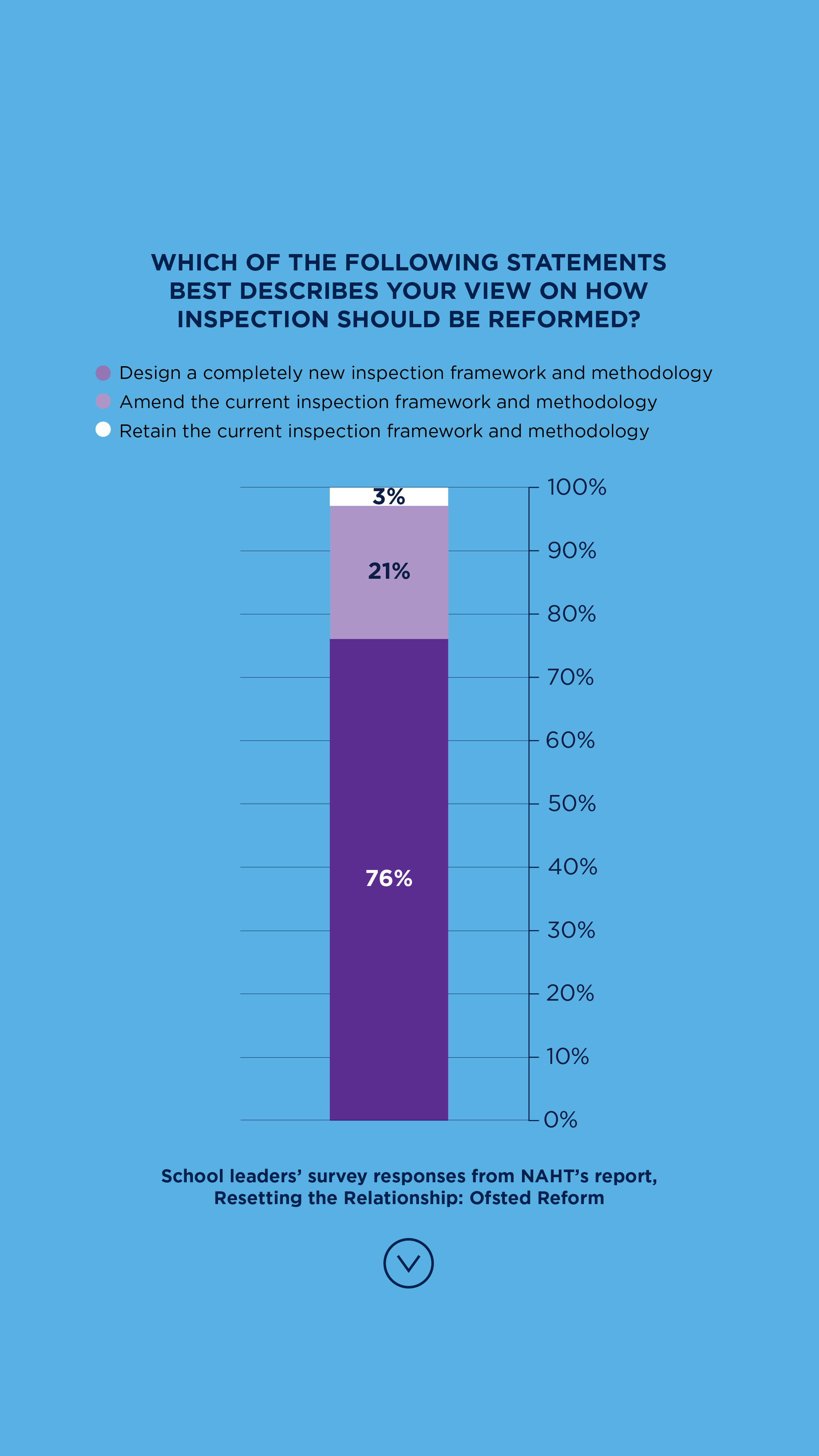

More than three-quarters (76%) believed a completely new framework and inspection methodology was needed, rejecting Ofsted’s suggestions that it simply needs to ‘evolve’ the current inspection system.

Around two-thirds (65%) agreed that the removal of headline grades would help reduce the stress of inspection. However, the notion of retaining ‘key sub-judgements’ – as Ofsted is proposing – was rejected by 75% of school leaders in the poll and is, argues Paul, a profound mistake.

“The plan to retain numbered sub-judgements risks replicating the worst aspects of the current system and will do little to reduce the enormous pressure school leaders are under,” he points out.

“We’re really disappointed with the approach that Ofsted has taken,” Paul tells Leadership Focus. “We’ve been talking to Ofsted about testing various models of inspection. It has now designed its preferred model, as this consultation shows, so we’re now discussing a single model. We think that is an opportunity missed.

“We would much rather have had a deeper or broader consultation that came up with a model that suits everybody. This approach will keep England as an outlier in the way that it inspects schools. Nonetheless, there is a consultation, and so we will, of course, encourage members to engage with it and make their views known,” he adds.

“Given that Ofsted previously struggled to provide reliable judgements across four or five areas using a four-point scale, it is very hard to see how it will be able to do so against a five-point one across up to ten areas. As other inspectorates have shown, there is another way – a way to provide clearer information for parents and schools without resorting to grades,” Paul continues.

“The decision to remove overarching judgements was absolutely the right one, and we welcome the confirmation these will not be returning, but as school leaders made clear at the time, that must be a first step towards fundamental reform of a broken system. School leaders do not want to see the evolution of a system that has caused so much harm over many years,” he adds.

These deep misgivings were clearly echoed in a snap NAHT poll of members in the immediate aftermath of the publication of the consultation. More than 3,000 responses were made in less than 48 hours, including more than 1,900 written free-text responses (some of which are featured as highlighted quotes in this article). On the question of whether members agreed or disagreed with the idea of five-point graded judgements across eight to ten ‘evaluation areas’, an overwhelming 92% disagreed.

There was deep scepticism about how likely they felt it was that Ofsted would make ‘meaningful’ changes in response to school leaders’ views as a result of the consultation. An almost unanimous 96% said ‘unlikely’.

For NAHT, however, this consultation – and, more widely, the whole process and, indeed, the pace of reform – is deeply problematic.

First, it simply does not recognise the scale of appetite for change within the profession – and the ongoing, lingering anger many feel at how little has changed two years on from Ruth Perry’s death.

Indeed, NAHT research published just a few weeks before the consultation document emphasised the scale of distrust and scepticism towards Ofsted among school leaders. More than nine in ten school leaders (93%) did not have confidence in Ofsted to design an effective new inspection framework.

More than three-quarters (76%) believed a completely new framework and inspection methodology was needed, rejecting Ofsted’s suggestions that it simply needs to ‘evolve’ the current inspection system.

Around two-thirds (65%) agreed that the removal of headline grades would help reduce the stress of inspection. However, the notion of retaining ‘key sub-judgements’ – as Ofsted is proposing – was rejected by 75% of school leaders in the poll and is, argues Paul, a profound mistake.

“The plan to retain numbered sub-judgements risks replicating the worst aspects of the current system and will do little to reduce the enormous pressure school leaders are under,” he points out.

“We’re really disappointed with the approach that Ofsted has taken,” Paul tells Leadership Focus. “We’ve been talking to Ofsted about testing various models of inspection. It has now designed its preferred model, as this consultation shows, so we’re now discussing a single model. We think that is an opportunity missed.

“We would much rather have had a deeper or broader consultation that came up with a model that suits everybody. This approach will keep England as an outlier in the way that it inspects schools. Nonetheless, there is a consultation, and so we will, of course, encourage members to engage with it and make their views known,” he adds.

“Given that Ofsted previously struggled to provide reliable judgements across four or five areas using a four-point scale, it is very hard to see how it will be able to do so against a five-point one across up to ten areas. As other inspectorates have shown, there is another way – a way to provide clearer information for parents and schools without resorting to grades,” Paul continues.

“The decision to remove overarching judgements was absolutely the right one, and we welcome the confirmation these will not be returning, but as school leaders made clear at the time, that must be a first step towards fundamental reform of a broken system. School leaders do not want to see the evolution of a system that has caused so much harm over many years,” he adds.

These deep misgivings were clearly echoed in a snap NAHT poll of members in the immediate aftermath of the publication of the consultation. More than 3,000 responses were made in less than 48 hours, including more than 1,900 written free-text responses (some of which are featured as highlighted quotes in this article). On the question of whether members agreed or disagreed with the idea of five-point graded judgements across eight to ten ‘evaluation areas’, an overwhelming 92% disagreed.

There was deep scepticism about how likely they felt it was that Ofsted would make ‘meaningful’ changes in response to school leaders’ views as a result of the consultation. An almost unanimous 96% said ‘unlikely’.

Timeline and consultation process issues

NAHT raises concerns over Ofsted’s consultation process, warning that its rushed timeline and reliance on numerical grading miss the opportunity for meaningful reform.

Then, as James emphasises, there are serious concerns about the consultation process itself. The consultation is running until 28 April 2025, with the intention that this new framework will go ‘live’ for the coming academic year (Ofsted has suggested November 2025 as a likely launch date).

“We think the idea of Ofsted publishing a consultation in February and then rolling out its changes to schools in the autumn term is far too quick. It is also very concerning in terms of Ofsted’s ability to really take on board and respond to what it hears through the consultation,” James worries.

“The consultation should be a genuine chance for them to listen and make changes accordingly. If the feedback is, ‘We think you have really got this wrong’, it will be very hard for Ofsted to respond, given that we will be halfway through the spring once the consultation closes. What do you do then? So, we are deeply concerned about the timeline.

“The other thing we’re saying is that even if it all does go to plan in the way Ofsted might hope, we’ll still have very limited time to give school leaders notice. We feel school leaders will need a good lead-in period to do this; there needs to be an engagement process from Ofsted explaining what the new framework means, and there needs to be time for leaders to get their heads around it. The current timescales make that pretty much impossible,” James explains.

The way the document, or listening process, is being framed and structured is also a concern. The document is an open consultation based on responses and views to open-ended free-text questions. Not only will this be more onerous for already time-poor school leaders to fill in, but it is also a concern that it shows Ofsted is not interested in gathering clear, quantitative feedback.

IAN HARTWRIGHT,

NAHT HEAD OF POLICY (PROFESSIONAL)

“Ofsted is being really careful not to ask any quantitative questions. That will make it very difficult to give a clear and precise picture of what people really think about this model,” points out Ian Hartwright, NAHT head of policy (professional).

“All of the drivers of workload are still there. So, effectively, there is not a lot of change happening. There is also this idea of a toolkit, but it is not really a toolkit at all. Instead, it is a list of what Ofsted describes as its ‘standards’ across its 11 areas – in other words, what schools should be meeting,” he adds.

“There is no doubt that getting rid of the over-arching grade has been and will continue to be a good thing,” says James. “But beyond that, Ofsted seems to be stuck in an old way of thinking: this absolute reliance on numbers, grades and things that you can put in spreadsheets and quantify. It is a massive missed opportunity to rethink things and formulate a radically different approach.

“The disappointment is that this is, really, just a different version of the same old thinking – the idea that if you can’t put a number on it, it is not worth evaluating. Meanwhile, we have been asking for something far more nuanced for schools and parents.

“Give some bullet points to schools about what is working and what they could improve on, perhaps? Why does everything have to be scored, ranked and numbered? Northern Ireland and Wales have moved away from numbers, so why can’t England? Our members, quite rightly, are asking, ‘If it is good enough for Wales and Northern Ireland, why isn’t it good enough for England?’” James says.

Challenges with Ofsted inspections and trust

While some improvements in Ofsted inspections are noted, NAHT leaders stress that trust remains low and call for a more radical overhaul of the accountability system.

“I think there has been progress. The feedback I’m getting from members who have been ‘Ofsted-ed’ is, by and large, encouraging,” concedes former NAHT president Simon Kidwell, head teacher at Hartford Manor Primary School and Nursery in Cheshire.

“But it is when it goes wrong that there still seems to be an issue. For example, I heard from a colleague the other day that their inspection took place in the autumn, and the school was judged to be ‘good’ after previously being rated ‘requires improvement’. However, Ofsted then decided to reinspect because it argued there wasn’t enough evidence. So, it came back just a few weeks after giving the school a ‘good’. The additional stress and pressure that created was immense; it felt to that member that there was still not enough safeguarding and support in terms of staff members’ and school leaders’ well-being,” he explains.

“When it goes wrong like this, does Ofsted have robust mechanisms in place to ensure schools can lodge a complaint or pause an Ofsted process to account for school leaders’ well-being? I think there are still issues that make it very difficult.

“For me, the power imbalance is still wrong, and that hasn’t been addressed. I hear from members that they are reluctant to file a complaint because they feel it is going to be negatively held against them. That is still an issue.

“There is a sense that Ofsted is not really listening. It is about trust, and trust in inspection is at an all-time low. Parents, too, don’t necessarily trust the inspection process. Without that trust – that Ofsted is a fair and accurate mechanism for judging the effectiveness of schools – I think it has a long way to go,” Simon adds.

Marijke Miles, head teacher at Baycroft School in Fareham, Hampshire, points to the fact that as far back as 2018 and its Accountability Commission, NAHT has outlined positive, constructive alternatives to the current accountability and inspection system – yet neither Ofsted nor the government has been willing to listen.

“There is that sense that Ofsted is still talking about evolution rather than revolution. But, really? The accountability process currently is radically wrong. So, we need radical intervention,” she tells Leadership Focus.

“In a way, this feels a bit disheartening because we have already presented a high-quality alternative to Ofsted – a very well-defined, peer-approved one: the Accountability Commission. We need to get that out again and say, ‘That is the model.’ There was a very high level of consensus around that.

“In the short term, the reports I am receiving from the front line are encouraging in terms of an improvement in the manner of Ofsted inspections at the moment, so that is positive. We have to celebrate where we have got to, which is far better than where we were.

“Overall, therefore, I’d say that for members, it is about still focusing on the improvements needed from their last inspection while remaining well-sighted on what might be possible for the next one – what is going to be a far more productive and worthwhile process, and what that is going to look like for them,” she adds.

Former NAHT president Simon Kidwell, head teacher at Hartford Manor Primary School and Nursery in Cheshire.

Former NAHT president Simon Kidwell, head teacher at Hartford Manor Primary School and Nursery in Cheshire.

Marijke Miles, head teacher at Baycroft School in Hampshire.

Marijke Miles, head teacher at Baycroft School in Hampshire.

Encouraging member participation

NAHT urges members to engage in the consultation, emphasising the need for clear, strong feedback to push for meaningful change.

Finally, as Paul touched on earlier, however flawed or misguided it may be, the fact is there is a consultation – and so, therefore, a chance for members to make their voices heard. And members should be taking that opportunity.

“What I would ask of members is that they take part not only in the consultation process – and we are issuing advice on that process – but also to be clear about what they’re saying. Because to give Ofsted credit where it’s due, it has said that if it gets a surprise in terms of the consultation, everything remains up for grabs,” he says.

“I would be very surprised if we went back to the drawing board. But if it’s an unambiguous ‘This is wrong’ from the profession, then I would very much hope Ofsted is true to its word. So, let’s see where we end up,” he adds.

James points out that NAHT has shared guidance with members on the consultation and how best to respond, which you can find here. “We want the consultation to be a genuine chance for Ofsted to listen and make changes accordingly,” he emphasises.

“We want as many members as possible to show what they think about this,” agrees Ian in conclusion. “I am quite angry about this; I am shocked at how little Ofsted has done: how it is sailing on down this road, which has killed people and is ruining the lives of our members. It is deeply frustrating.”

What Ofsted

is proposing

Ofsted’s proposal includes a new grading system, revised inspection methods and full inspections expected to begin in November 2025.

The Ofsted consultation runs until 28 April 2025. In addition to the online survey, which you can find here, Ofsted is holding focus groups during the consultation period. Formal pilots of the inspection approach and further user testing of report cards are also being carried out to help inform and improve the proposals.

Ofsted will publish a report on the outcome of the consultation in the summer, reflecting on all feedback and challenges received. The final agreed reforms will then be piloted across all education remits before being formally implemented in autumn 2025, likely in November. Changes to children’s social care inspections will follow in 2026.

Ofsted is proposing a model based on report cards, education inspection toolkits, a reformed inspection methodology and a reformed inspection process. Looking therefore at each in turn:

Report cards

The aim here is, as the main article outlined, to use a five-point scale to grade different – and a greater number of – areas of a provider’s work, such as ‘curriculum’ and ‘leadership’.

Alongside grades, there would be short descriptions summarising the findings. These evaluations, Ofsted has said, would make up new education inspection report cards. “There will be no overall effectiveness grade for early years, state-funded schools, non-association independent schools, further education (FE) and skills, or initial teacher education (ITE) inspections,” it added.

“We believe this approach brings together the most popular preferences of parents and professionals. We also believe it provides the nuance that both are looking for. We will clearly tell parents and the public what a provider is doing well and where further work is needed. And we hope the clear move away from an overall effectiveness grade will also reduce anxiety for professionals,” it said.

The evaluation areas for all schools would be as follows: leadership and governance; curriculum; developing teaching; achievement; behaviour and attitudes; attendance; personal development and well-being; inclusion; safeguarding; early years in schools (where applicable); and sixth form in schools (where applicable).

There would also be further evaluation areas for early years providers and FE and skills providers.

Education inspection toolkits

These would contain the standards against which Ofsted inspects providers. “These standards, across a range of evaluation areas, are underpinned by statutory and non-statutory guidance, professional frameworks and expectations, and research relevant to the different stages and types of education,” Ofsted explained.

There would be separate toolkits for early years, state-funded schools, non-association independent schools, FE and skills, and ITE.

Inspection methodology

Ofsted said: “We want to change both how inspection looks and how it feels. This is especially important at the point of professional interaction and conversation between inspectors and leaders. To do this, we will instil our core values of professionalism, courtesy, empathy and respect.”

Before the on-site part of an inspection, there would still be initial phone or video conversations with leaders. Ofsted would no longer use the deep-dive methodology. “Removing deep dives will give inspectors and providers significantly greater flexibility. Currently, during a typical school inspection, a large portion of day one and up to lunchtime on day two is dedicated to deep dives, for example,” Ofsted said.

“By eliminating deep dives, this substantial amount of time can be used more flexibly, to allow leaders and inspectors to reflect on each provider’s unique context and their improvement priorities.

“Our evaluation also found that the focus on curriculum quality across all subjects had unintentionally put pressure on some staff with subject roles. Instead of deep dives, inspectors will work with leaders as they decide the areas to focus on. Inspectors will discuss the most appropriate activities tailored to the specific provider. These will typically mirror leaders’ improvement priorities. Inspectors will explore the impact of any actions since the last inspection,” the inspectorate’s consultation added.

The aim, too, would be to avoid adding to leaders’ workloads. “We want it to come together with the everyday business of running a provider so that it does not detract leaders from what they are already doing to continuously improve their provision.

“To support this approach, our toolkits will take account of the standards and expectations already placed on leaders and their provision. This includes statutory and non-statutory guidance, professional standards and the educational research that suggests the most effective strategies in securing better outcomes for all learners,” Ofsted said.

The inspection process

Under the consultation plans, starting from November 2025, all inspections would be ‘full’ inspections. “We will no longer do ungraded inspections. This will simplify inspection: every school will know exactly what kind of inspection it will receive and how often,” Ofsted said.

All schools with an identified need for improvement would receive monitoring. This would include the following: schools causing concern and schools with any evaluation area identified as ‘attention needed’ under the new toolkit.

It would also include schools that, before November 2025, received a ‘requires improvement’ overall effectiveness judgement and schools that currently do not have an overall effectiveness judgement but have any key judgements graded ‘requires improvement’.

You’ve read the feature – Now hear the debate

This feature has explored Ofsted’s proposed reforms in depth – but the discussion doesn’t end here. In this episode of The School Leadership Podcast, NAHT’s Paul Whiteman and James Bowen take the debate further, breaking down the changes and challenging whether they will truly ease pressure on schools or simply repackage the same issues.

Lively, insightful and unafraid to ask the tough questions, this is essential listening for anyone wanting to engage with the reforms before the consultation closes on 28 April 2025.

You can find The School Leadership Podcast wherever you listen to podcasts – where you can also rate, review and subscribe.