Leadership Focus journalist Nic Paton asks, will a real-terms pay cut and erosion of pay differentials tip the profession over the edge?

“A ‘slap in the face’ doesn’t even begin to cover it.” Is this the best head teachers and other school leaders can expect this autumn on future pay after grinding their way through perhaps the most challenging, most intense 12 months anyone in the profession can remember?

If NAHT’s evidence this year to the School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB) is anything to go by – and it uses the very words above – the fear is this is precisely the catastrophic outcome coming down the track, given chancellor Rishi Sunak’s announcement in November that all public sector workers outside of the NHS and the lowest earners can expect a pay freeze in 2021/22.

As the report, designed to feed into the STRB’s 31st remit and deliberations, puts it: “Delivering yet another real-terms pay cut to a profession where recruitment and retention are through the floor is inexplicable; doing so where that profession is reeling from the huge costs to individual professionals of supporting young people, families and communities through a global pandemic is simply incomprehensible.”

Arguably, even though it is the usual authoritative, nuanced and comprehensive document that NAHT submits to the STRB every year, there is both weariness and a palpable sense of anger in this year’s evidence.

The weariness that here the profession is, again, making much the same arguments it does every year to a body that, by and large, accepts their merit, again, but yet which will – probably, again – end up being ignored or overruled at the end of the process.

IAN HARTWRIGHT,

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISOR

As Ian Hartwright, NAHT senior policy advisor, explains to Leadership Focus: “The review body’s work is increasingly fettered. It recognises more and more what we say each year. But then, each year, the next remit tries to stop it from doing that. The STRB ‘gets’ this; it understands the issues the profession is facing. But will it be thwarted once again from looking at things in the right way?

“The government has, yet again, said there is no money and that there has to be a pay cap. The government has come back time and again to a position that the best way to control this is not even to argue, but instead, to just say ‘you can’t have a pay rise’. So, we’re back to a pay freeze again.

“We need to challenge the secretary of state and his remit; there is a litany of missed opportunities to resolve, not least the recruitment and retention crisis at all levels within the profession.”

This is where the anger and, in truth, genuine fear for the future comes in. Running through this year’s report is the sense that after a year when the professionalism, dedication and, crucially, goodwill of the profession across the board have been tested to the absolute limit by covid-19, the effect of the pandemic combined with yet another year of pay erosion and erosion of pay differentials could tip the profession’s recruitment and retention crisis over the edge.

This sense of things being on a tipping point was also clear in a series of panel discussions with NAHT members held during the autumn to feed into the evidence-gathering process, and we will revisit these in more detail later on. The fear is that the very sustainability of the professional teaching leadership role – the ability to enjoy and gain rewards (in all senses, including financial) from being a school leader, whatever your level, and the attractiveness of that as an aspiration – is being called into question; with pay just one part of an increasingly toxic triumvirate (the triumvirate of pay, workload and accountability, which has been amplified by the effects of the pandemic).

“Throughout the pandemic, the government has really sought to pick a fight with teachers rather than support them. This is corrosive; this approach to teachers’ pay is absolutely corrosive,” emphasises Ian.

What arguments, then, is NAHT making this year to the STRB in its evidence? The ongoing recruitment and retention crisis at all levels, but especially among senior and middle leaders, is starkly reiterated.

The report highlights the widespread concern that “the intractable crisis affecting the supply of teachers and leaders in English schools has been further sharpened by the multiple impacts of the covid-19 pandemic on schools.”

The ‘largely unaddressed’ issue of teacher and – to an even greater extent – leadership retention, remains, it says. Indeed, it is likely to be a crisis that is only accelerated by the pandemic. “Last year’s recruitment rounds suggest that many teachers and leaders may have postponed future career decisions, creating the potential for very significant losses of experienced professionals when the pressure of the pandemic is released,” the report states.

“It is possible that there may be an outflow from the profession, particularly of late-career teachers and leaders exhausted by a year of constant crisis management and the inadequacy and incompetence of the government’s chaotic approach to the school sector. NAHT is deeply concerned about the impact that the government’s loss of trust and confidence of the profession may have,” it warns.

The evidence highlights how the STRB has been ‘hemmed in’ by repeated public sector pay freezes, pay caps and ‘other interference’ in its role by the government. Ministers are unwilling “to allow the pay body to make a full and independent assessment of the challenges and solutions to the parlous state of teacher and leadership supply,” it contends.

“NAHT is genuinely shocked by the paltry and insufficient remit that the secretary of state has set for the review body’s consideration in this pay round,” it adds.

Much as it has been in so many areas of public life and discourse over the past year, the pandemic is a recurring theme. The report highlights how the profession has stepped up and responded magnificently from the first lockdown last year and onwards.

“School leaders and their teams have operated as an essential public service throughout the pandemic. They switched, literally overnight, from on-site to the delivery of remote learning – something never planned for,” the report outlines.

“They remained open throughout to children of critical workers and vulnerable pupils. They worked with next to no protection in poorly ventilated spaces where it is impossible to maintain social distance. They ensured those eligible for free school meals were fed – before the government acted and when its voucher scheme provider failed to deliver. They operated the tracking and tracing of infections in their schools. And throughout, most school leaders have worked during their holidays and weekends since February 2020,” it makes clear.

And yet, ‘at this extraordinary time’, the government has decided to press ahead once again with another pay freeze on all teaching professionals, apart from unqualified teachers earning less than £24,000 per annum.

“A ‘slap in the face’ doesn’t even begin to cover it.” Is this the best head teachers and other school leaders can expect this autumn on future pay after grinding their way through perhaps the most challenging, most intense 12 months anyone in the profession can remember?

If NAHT’s evidence this year to the School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB) is anything to go by – and it uses the very words above – the fear is this is precisely the catastrophic outcome coming down the track, given chancellor Rishi Sunak’s announcement in November that all public sector workers outside of the NHS and the lowest earners can expect a pay freeze in 2021/22.

As the report, designed to feed into the STRB’s 31st remit and deliberations, puts it: “Delivering yet another real-terms pay cut to a profession where recruitment and retention are through the floor is inexplicable; doing so where that profession is reeling from the huge costs to individual professionals of supporting young people, families and communities through a global pandemic is simply incomprehensible.”

Arguably, even though it is the usual authoritative, nuanced and comprehensive document that NAHT submits to the STRB every year, there is both weariness and a palpable sense of anger in this year’s evidence.

The weariness that here the profession is, again, making much the same arguments it does every year to a body that, by and large, accepts their merit, again, but yet which will – probably, again – end up being ignored or overruled at the end of the process.

IAN HARTWRIGHT,

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISOR

As Ian Hartwright, NAHT senior policy advisor, explains to Leadership Focus: “The review body’s work is increasingly fettered. It recognises more and more what we say each year. But then, each year, the next remit tries to stop it from doing that. The STRB ‘gets’ this; it understands the issues the profession is facing. But will it be thwarted once again from looking at things in the right way?

“The government has, yet again, said there is no money and that there has to be a pay cap. The government has come back time and again to a position that the best way to control this is not even to argue, but instead, to just say ‘you can’t have a pay rise’. So, we’re back to a pay freeze again.

“We need to challenge the secretary of state and his remit; there is a litany of missed opportunities to resolve, not least the recruitment and retention crisis at all levels within the profession.”

This is where the anger and, in truth, genuine fear for the future comes in. Running through this year’s report is the sense that after a year when the professionalism, dedication and, crucially, goodwill of the profession across the board have been tested to the absolute limit by covid-19, the effect of the pandemic combined with yet another year of pay erosion and erosion of pay differentials could tip the profession’s recruitment and retention crisis over the edge.

This sense of things being on a tipping point was also clear in a series of panel discussions with NAHT members held during the autumn to feed into the evidence-gathering process, and we will revisit these in more detail later on. The fear is that the very sustainability of the professional teaching leadership role – the ability to enjoy and gain rewards (in all senses, including financial) from being a school leader, whatever your level, and the attractiveness of that as an aspiration – is being called into question; with pay just one part of an increasingly toxic triumvirate (the triumvirate of pay, workload and accountability, which has been amplified by the effects of the pandemic).

“Throughout the pandemic, the government has really sought to pick a fight with teachers rather than support them. This is corrosive; this approach to teachers’ pay is absolutely corrosive,” emphasises Ian.

What arguments, then, is NAHT making this year to the STRB in its evidence? The ongoing recruitment and retention crisis at all levels, but especially among senior and middle leaders, is starkly reiterated.

The report highlights the widespread concern that “the intractable crisis affecting the supply of teachers and leaders in English schools has been further sharpened by the multiple impacts of the covid-19 pandemic on schools.”

The ‘largely unaddressed’ issue of teacher and – to an even greater extent – leadership retention, remains, it says. Indeed, it is likely to be a crisis that is only accelerated by the pandemic. “Last year’s recruitment rounds suggest that many teachers and leaders may have postponed future career decisions, creating the potential for very significant losses of experienced professionals when the pressure of the pandemic is released,” the report states.

“It is possible that there may be an outflow from the profession, particularly of late-career teachers and leaders exhausted by a year of constant crisis management and the inadequacy and incompetence of the government’s chaotic approach to the school sector. NAHT is deeply concerned about the impact that the government’s loss of trust and confidence of the profession may have,” it warns.

The evidence highlights how the STRB has been ‘hemmed in’ by repeated public sector pay freezes, pay caps and ‘other interference’ in its role by the government. Ministers are unwilling “to allow the pay body to make a full and independent assessment of the challenges and solutions to the parlous state of teacher and leadership supply,” it contends.

“NAHT is genuinely shocked by the paltry and insufficient remit that the secretary of state has set for the review body’s consideration in this pay round,” it adds.

Much as it has been in so many areas of public life and discourse over the past year, the pandemic is a recurring theme. The report highlights how the profession has stepped up and responded magnificently from the first lockdown last year and onwards.

“School leaders and their teams have operated as an essential public service throughout the pandemic. They switched, literally overnight, from on-site to the delivery of remote learning – something never planned for,” the report outlines.

“They remained open throughout to children of critical workers and vulnerable pupils. They worked with next to no protection in poorly ventilated spaces where it is impossible to maintain social distance. They ensured those eligible for free school meals were fed – before the government acted and when its voucher scheme provider failed to deliver. They operated the tracking and tracing of infections in their schools. And throughout, most school leaders have worked during their holidays and weekends since February 2020,” it makes clear.

And yet, ‘at this extraordinary time’, the government has decided to press ahead once again with another pay freeze on all teaching professionals, apart from unqualified teachers earning less than £24,000 per annum.

NAHT is also urging the STRB “to set out a recommended pay uplift for all teachers and leaders for this pay round. It is then a matter for the government to determine whether it wishes to accept that recommendation”.

This, NAHT adds, “should identify the minimum uplift required to remove pay disincentives to leadership by restoring the losses to leaders’ real salaries accumulated over the last decade and reverse the decline in the leadership differential, as a minimum”.

School leaders, the report emphasises, are increasingly stretched, exhausted and unhappy with their lot. For middle leaders, the prospect of stepping up into the head teacher spotlight is becoming an increasingly unattractive proposition.

Intriguingly, it was less the pandemic itself that was the most challenging aspect of this, but the government’s erratic and often late notice response to it, members stressed.

As the report puts it: “NAHT is very concerned that this points to an exodus of late-career school leaders from the profession when the pandemic eases. Many members tell us that they have felt a responsibility to guide their schools through this extraordinary period, but they intend to leave the profession at its conclusion.”

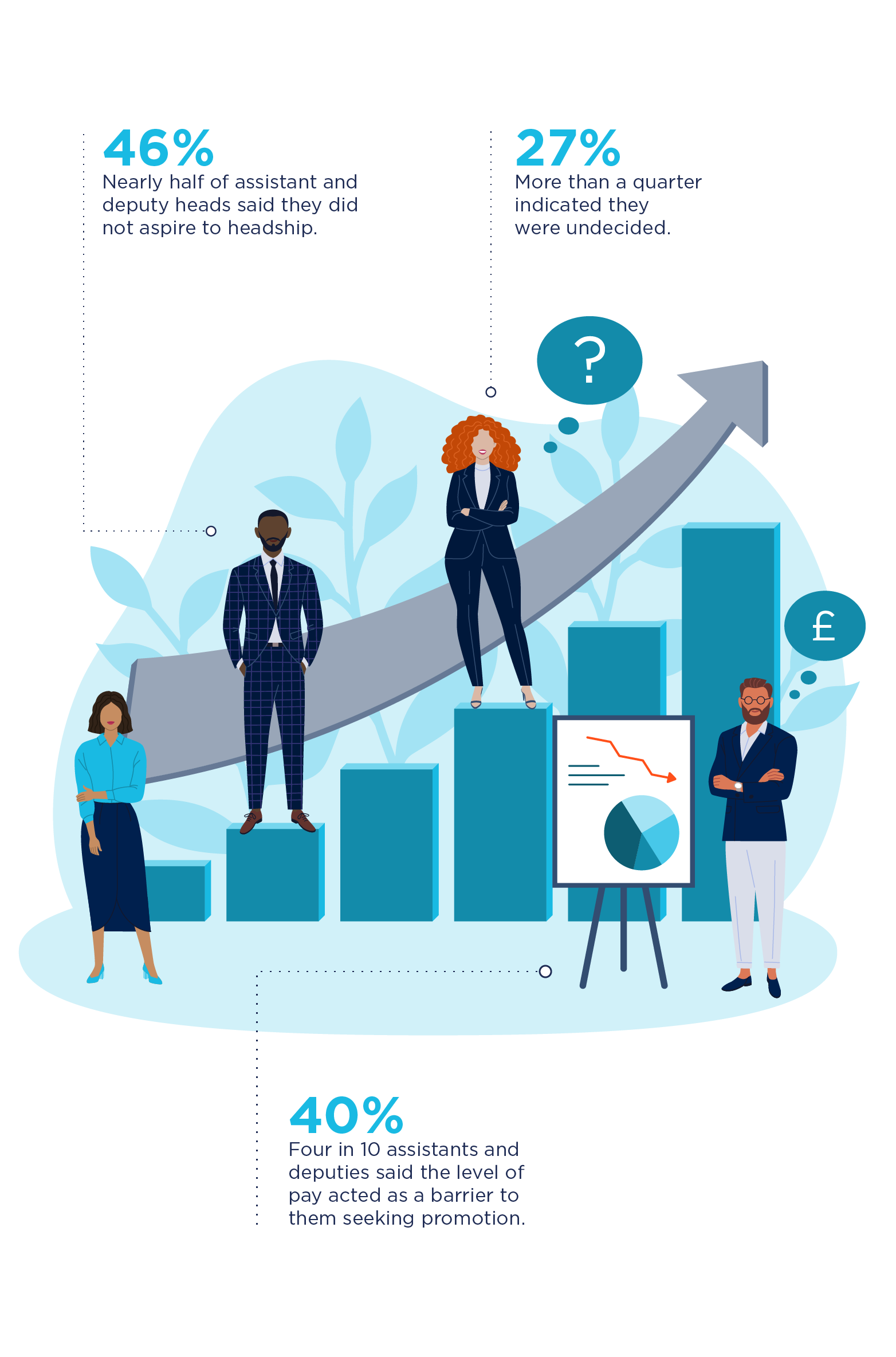

Equally worrying, the report highlights a similarly gloomy picture of the future supply of head teachers – what it terms ‘the aridity’ of the leadership supply pipeline. Nearly half (46%) of assistant and deputy heads said they did not aspire to headship, while more than a quarter (27%) indicated they were undecided.

Within this, pay was an important disincentive. Four in 10 (40%) assistants and deputies said the level of pay acted as a barrier to them seeking promotion, with ‘insufficient’ and ‘inadequate’ being the most common words used. This was, again, a theme that came through clearly in the panel discussions with members, which we shall come to shortly.

The report concludes with a warning of the potentially catastrophic consequences of, as it puts it, ‘another year without progress’; a year of worsening problems in the leadership pipeline and continuing ‘aridity’ of leadership supply.

Without positive engagement – and a better pay settlement – leaders will continue to report low morale and anger. And this has been exacerbated by the past year of pandemic and crisis, where the pressures and pinch points facing leaders have increased exponentially. As the report argues: “Teachers and leaders have confronted their greatest ever challenge in the face of a pandemic event for which they had no time to plan or prepare.

“At every turn, they encountered the government’s obduracy and incompetence: from chaotic food voucher schemes and contradictory, poorly timed guidance; to examination chaos, inadequate funding for covid-19 costs and ill-informed ministerial diktat divorced from the realities on the ground.”

With leadership supply, even in the previous pay round, teetering ‘on the verge of catastrophic collapse’, now was not the time to be freezing pay.

As the report argues: “A real-terms pay cut for teachers and leaders in these circumstances is both tin-eared and wrong-headed. The urgent need to support leadership retention has not changed. Nor has the need for a full and concurrent review of the teachers’ and leaders’ pay structure in order to develop a compelling proposition that will retain experienced teachers and leaders.

“We urge the STRB to set out to the government a vision of a decades-long career in education, with clear career and salary progression points and flexible, sustainable career pathways that are underpinned by appropriate opportunities for funded training and development.

“There must be an attractive premium for leadership that is progressive, predictable and commensurate with responsibility. And the real value of leadership pay must be protected over time,” it concludes.

As the report puts it: “NAHT is very concerned that this points to an exodus of late-career school leaders from the profession when the pandemic eases. Many members tell us that they have felt a responsibility to guide their schools through this extraordinary period, but they intend to leave the profession at its conclusion.”

Equally worrying, the report highlights a similarly gloomy picture of the future supply of head teachers – what it terms ‘the aridity’ of the leadership supply pipeline. Nearly half (46%) of assistant and deputy heads said they did not aspire to headship, while more than a quarter (27%) indicated they were undecided.

Within this, pay was an important disincentive. Four in 10 (40%) assistants and deputies said the level of pay acted as a barrier to them seeking promotion, with ‘insufficient’ and ‘inadequate’ being the most common words used. This was, again, a theme that came through clearly in the panel discussions with members, which we shall come to shortly.

The report concludes with a warning of the potentially catastrophic consequences of, as it puts it, ‘another year without progress’; a year of worsening problems in the leadership pipeline and continuing ‘aridity’ of leadership supply.

Without positive engagement – and a better pay settlement – leaders will continue to report low morale and anger. And this has been exacerbated by the past year of pandemic and crisis, where the pressures and pinch points facing leaders have increased exponentially. As the report argues: “Teachers and leaders have confronted their greatest ever challenge in the face of a pandemic event for which they had no time to plan or prepare.

“At every turn, they encountered the government’s obduracy and incompetence: from chaotic food voucher schemes and contradictory, poorly timed guidance; to examination chaos, inadequate funding for covid-19 costs and ill-informed ministerial diktat divorced from the realities on the ground.”

With leadership supply, even in the previous pay round, teetering ‘on the verge of catastrophic collapse’, now was not the time to be freezing pay.

As the report argues: “A real-terms pay cut for teachers and leaders in these circumstances is both tin-eared and wrong-headed. The urgent need to support leadership retention has not changed. Nor has the need for a full and concurrent review of the teachers’ and leaders’ pay structure in order to develop a compelling proposition that will retain experienced teachers and leaders.

“We urge the STRB to set out to the government a vision of a decades-long career in education, with clear career and salary progression points and flexible, sustainable career pathways that are underpinned by appropriate opportunities for funded training and development.

“There must be an attractive premium for leadership that is progressive, predictable and commensurate with responsibility. And the real value of leadership pay must be protected over time,” it concludes.

HOW MEMBERS’ PANELS FED INTO THE PAY DEBATE

In 2019, NAHT held a members-led roundtable panel to discuss the challenges around leadership pay – particularly how pay and remuneration fed into, and often contributed to, wider barriers to progression, recruitment and retention.

The event aimed to inform and feed into the evidence NAHT submitted that year to the STRB. That format proved so successful that NAHT decided last year to expand the process to three events – which, because of the pandemic, were carried out virtually – with deputy and assistant heads coming together, followed by head teachers and then a third event looking at pay in the context of inclusion, diversity and equalities.

Individual reports were generated from each discussion, which fed into the conversations and evidence building that took place around the creation of this year’s document.

The thread that ran through each event, much as it does in the final evidence, was the sense of a profession wrestling with perhaps the most challenging year ever, yet with none of the pre-existing pressures and tensions having gone away.

DISINCENTIVES TO PROGRESSION

For deputy and assistant heads (DAHs), it was clear that pay (or the lack of it) was by no means the only disincentive when it came to progression, but it was nevertheless an important one. There also needed to be a model for progression that allows people to advance in their career without necessarily having to move into senior management (for example, by becoming classroom specialists), the panel argued.

The ‘trust gap’ between the government and profession combined with seeing high-stakes accountability in action and intense (and intensifying) workload pressures on DAHs were all acting as a disincentive to DAHs to take the risk of stepping up. Alongside this, dedicated leadership time was too often being squeezed or eroded by spiralling day-to-day demands.

“I am stretched as it is at the minute; I am finding every day a challenge in a different way.

“So, part of me is thinking ‘if I am finding this challenging, why on earth at this point in time would I consider moving into a headship?’.

“I do want to be a head teacher; I do want to have my own school. But I just think of the leap from where I am currently to being a head teacher and the accountability that comes with it. I have two children, and they are really important to me; I know I work long hours as it is at the minute. And I worry that I would lose that work-life balance if I were a head teacher.

“If you look at pay across a school, you will have some teachers who are on the upper pay scale, who are possibly on only a little less than some assistant or deputy heads,” Claire explained.

“It [headship] is just not for me,” agreed Heather Martin, executive assistant principal across two primary schools in Blackpool. “And, in terms of pay, it is not worth me applying in lots of respects. I am quite well paid for the job I do currently. But for me to go to a head teacher role somewhere else, I would be taking a pay cut for some jobs.

“For me, the question would be ‘what would be the incentive for me to take on that extra responsibility again for either a pay cut or very little [extra] pay?’,” she said.

HOW MEMBERS’ PANELS FED INTO THE PAY DEBATE

In 2019, NAHT held a members-led roundtable panel to discuss the challenges around leadership pay – particularly how pay and remuneration fed into, and often contributed to, wider barriers to progression, recruitment and retention.

The event aimed to inform and feed into the evidence NAHT submitted that year to the STRB. That format proved so successful that NAHT decided last year to expand the process to three events – which, because of the pandemic, were carried out virtually – with deputy and assistant heads coming together, followed by head teachers and then a third event looking at pay in the context of inclusion, diversity and equalities.

Individual reports were generated from each discussion, which fed into the conversations and evidence building that took place around the creation of this year’s document.

The thread that ran through each event, much as it does in the final evidence, was the sense of a profession wrestling with perhaps the most challenging year ever, yet with none of the pre-existing pressures and tensions having gone away.

DISINCENTIVES TO PROGRESSION

For deputy and assistant heads (DAHs), it was clear that pay (or the lack of it) was by no means the only disincentive when it came to progression, but it was nevertheless an important one. There also needed to be a model for progression that allows people to advance in their career without necessarily having to move into senior management (for example, by becoming classroom specialists), the panel argued.

The ‘trust gap’ between the government and profession combined with seeing high-stakes accountability in action and intense (and intensifying) workload pressures on DAHs were all acting as a disincentive to DAHs to take the risk of stepping up. Alongside this, dedicated leadership time was too often being squeezed or eroded by spiralling day-to-day demands.

“I am stretched as it is at the minute; I am finding every day a challenge in a different way.

“So, part of me is thinking ‘if I am finding this challenging, why on earth at this point in time would I consider moving into a headship?’.

“I do want to be a head teacher; I do want to have my own school. But I just think of the leap from where I am currently to being a head teacher and the accountability that comes with it. I have two children, and they are really important to me; I know I work long hours as it is at the minute. And I worry that I would lose that work-life balance if I were a head teacher.

“If you look at pay across a school, you will have some teachers who are on the upper pay scale, who are possibly on only a little less than some assistant or deputy heads,” Claire explained.

“It [headship] is just not for me,” agreed Heather Martin, executive assistant principal across two primary schools in Blackpool. “And, in terms of pay, it is not worth me applying in lots of respects. I am quite well paid for the job I do currently. But for me to go to a head teacher role somewhere else, I would be taking a pay cut for some jobs.

“For me, the question would be ‘what would be the incentive for me to take on that extra responsibility again for either a pay cut or very little [extra] pay?’,” she said.

LOSS OF EXPERIENCED HEAD TEACHERS

It was a similar story when it came to head teachers and other school leaders. While the panellists broadly conceded that pay was not the main driver for them in their roles – it was often as much about placemaking and being able to shape a school and community – it was nevertheless an important element of the whole head teacher ‘package’.

The erosion of pay differentials combined with the workload and lack of funding were all seen as factors that deterred senior leaders from stepping up. They were also seen as reasons for the profession losing experienced head teachers. There were real fears around how the profession will retain its older head teachers, especially those 55 and older who could still cash in their pensions early.

On top of this, the panellists were worried about a trend towards early progression into senior leadership levels, potentially creating a problem of burnout and retention further down the track. The workload for head teachers right now is relentless, especially with covid-19, and many head teachers and senior leaders are totally exhausted, they added.

“When I meet with head teachers, deputies, other school leaders, etc., the vast majority of them have said the last year has been relentless,” pointed out Ian Taylor, a former primary school head teacher in Southampton. “They are exhausted; they can’t see an end to it. There is new guidance coming out all the time. We have some very tired and overwhelmed school leaders out there, and of course, that means they may start thinking about their options. Like, do I need to get out?

“So, potentially, I see an issue with retention coming up for those who are maybe close to, or even above, the age of 55, the earliest point for being able to draw your pension. So, that is a big concern. How are we going to retain our valuable, experienced school leaders? How are we going to get people to apply for senior leadership?”

Stuart Beck, currently in semi-retirement from teaching and school management and working part-time as a consultant senior leader at Sacred Heart of Mary Girls’ School in Upminster, added: “My wife was a deputy head teacher in a four-form entry primary school and moved to become a head teacher of a three-form entry primary school. She took a significant pay cut to become a head teacher. So, we don’t just do it for the money.

“But also, you can’t just be totally altruistic about your future.

“Your endgame needs to be recognised and rewarded. Head teachers can have this ingrained culture of thinking about other people first.

“And, with funding, I agree that is crucial. It can get really difficult when you are plugging the gaps and not doing your strategic jobs properly, and that can cause issues for the school if you’re not careful,” he said.

“Most of us spent the holidays writing risk assessments and trying to work out how children could come back. So, how much more pressure is there on our shoulders?

“When you take on headship and some other senior roles, you feel the weight of the world all of a sudden pressing down on you. You only often get rid of that for a couple of weeks in the summer; it is quite oppressive and damaging. And most of us live our lives with that.

“It is really interesting talking to friends who have retired. Almost on the day of retirement, they have felt that weight of responsibility – responsibility for 200 children, the parents and the teaching staff – lifted. You multiply that up, and that is an awful lot of relationships and responsibility that you have,” Paul explained.

LOSS OF EXPERIENCED HEAD TEACHERS

It was a similar story when it came to head teachers and other school leaders. While the panellists broadly conceded that pay was not the main driver for them in their roles – it was often as much about placemaking and being able to shape a school and community – it was nevertheless an important element of the whole head teacher ‘package’.

The erosion of pay differentials combined with the workload and lack of funding were all seen as factors that deterred senior leaders from stepping up. They were also seen as reasons for the profession losing experienced head teachers. There were real fears around how the profession will retain its older head teachers, especially those 55 and older who could still cash in their pensions early.

On top of this, the panellists were worried about a trend towards early progression into senior leadership levels, potentially creating a problem of burnout and retention further down the track. The workload for head teachers right now is relentless, especially with covid-19, and many head teachers and senior leaders are totally exhausted, they added.

“When I meet with head teachers, deputies, other school leaders, etc., the vast majority of them have said the last year has been relentless,” pointed out Ian Taylor, a former primary school head teacher in Southampton. “They are exhausted; they can’t see an end to it. There is new guidance coming out all the time. We have some very tired and overwhelmed school leaders out there, and of course, that means they may start thinking about their options. Like, do I need to get out?

“So, potentially, I see an issue with retention coming up for those who are maybe close to, or even above, the age of 55, the earliest point for being able to draw your pension. So, that is a big concern. How are we going to retain our valuable, experienced school leaders? How are we going to get people to apply for senior leadership?”

Stuart Beck, currently in semi-retirement from teaching and school management and working part-time as a consultant senior leader at Sacred Heart of Mary Girls’ School in Upminster, added: “My wife was a deputy head teacher in a four-form entry primary school and moved to become a head teacher of a three-form entry primary school. She took a significant pay cut to become a head teacher. So, we don’t just do it for the money.

“But also, you can’t just be totally altruistic about your future.

“Your endgame needs to be recognised and rewarded. Head teachers can have this ingrained culture of thinking about other people first.

“And, with funding, I agree that is crucial. It can get really difficult when you are plugging the gaps and not doing your strategic jobs properly, and that can cause issues for the school if you’re not careful,” he said.

“Most of us spent the holidays writing risk assessments and trying to work out how children could come back. So, how much more pressure is there on our shoulders?

“When you take on headship and some other senior roles, you feel the weight of the world all of a sudden pressing down on you. You only often get rid of that for a couple of weeks in the summer; it is quite oppressive and damaging. And most of us live our lives with that.

“It is really interesting talking to friends who have retired. Almost on the day of retirement, they have felt that weight of responsibility – responsibility for 200 children, the parents and the teaching staff – lifted. You multiply that up, and that is an awful lot of relationships and responsibility that you have,” Paul explained.

LACK OF DIVERSITY AT THE TOP

For the third and final discussion – on equalities, diversity and inclusion – there was a recognition that the profession and government alike needed to examine why there is diversity at teacher level, but this then dissipates at more senior and leadership levels. The profession also needed to get better at attracting and retaining people with disabilities and other protected characteristics. To do this, it needed to include intersectionality.

Schools could be better at being more flexible about jobs and roles to attract and recruit the best (as well as the most diverse) candidates into them. This needed to include potentially adjusting the role to fit the candidate rather than expecting the candidate to fit the role (and, as a result, perhaps not feeling able to apply in the first place). Within this, the erosion of pay differentials was one factor that could potentially exacerbate existing barriers to progression or stepping up that have been caused by inequalities, the panel agreed.

“We do need to develop the diversity within the profession,” argued Patrick Foley, head teacher of a two-form entry primary school in the London borough of Bromley. “We don’t look at our equalities pay gap; we just look at the profession and who is working in schools. There is a higher level of ethnic diversity in lower-paid groupings than in higher-paid groupings.

“We need to think of how we address these issues. In a school-like environment, it is a really bad message to give to children that members of their ethnic group are lower paid by nature; it is a really dangerous issue that we need to address.

“And I think the third issue is that the process of performance management for head teachers is really poor in terms of its understanding of diversity,” Patrick pointed out.

“If governors want to keep female leaders, is there some way we can train them up or teach them how to negotiate to get a good bit of pay, rather than just sitting there on low pay the whole time and then eventually thinking ‘well, I can stay on low pay or go to a bigger school’? I think that is an issue with the gender gap for women and small schools,” she added.

“I know we’re not just talking about head teachers, but if you think of the make-up of those governing bodies. Certainly, in my experience, there has been very little ethnic diversity across the governing body.

“Even when I worked in an area where 70% of the children were non-white British, the governing body was all-white British. So, there is an issue around governance and making sure there is representation at governance levels because I think that may have an impact on recruitment and at senior and head teacher level,” he added.

“It shouldn’t need a crisis to encourage us as a profession to look differently at how we recruit, how we retain, how we support our colleagues and how we develop our colleagues.

“If we don’t understand where the profession is at the moment, then how can we shape it into what we want it to be and enable it to become far more diverse? There is very limited research in terms of why people from diverse backgrounds or backgrounds of protected characteristics might join the profession; we don’t hear a lot about that. And if we don’t know why they’re coming in the first place, then we can’t develop them, can we? Or then encourage others to come and join them,” he added.

LACK OF DIVERSITY AT THE TOP

For the third and final discussion – on equalities, diversity and inclusion – there was a recognition that the profession and government alike needed to examine why there is diversity at teacher level, but this then dissipates at more senior and leadership levels. The profession also needed to get better at attracting and retaining people with disabilities and other protected characteristics. To do this, it needed to include intersectionality.

Schools could be better at being more flexible about jobs and roles to attract and recruit the best (as well as the most diverse) candidates into them. This needed to include potentially adjusting the role to fit the candidate rather than expecting the candidate to fit the role (and, as a result, perhaps not feeling able to apply in the first place). Within this, the erosion of pay differentials was one factor that could potentially exacerbate existing barriers to progression or stepping up that have been caused by inequalities, the panel agreed.

“We do need to develop the diversity within the profession,” argued Patrick Foley, head teacher of a two-form entry primary school in the London borough of Bromley. “We don’t look at our equalities pay gap; we just look at the profession and who is working in schools. There is a higher level of ethnic diversity in lower-paid groupings than in higher-paid groupings.

“We need to think of how we address these issues. In a school-like environment, it is a really bad message to give to children that members of their ethnic group are lower paid by nature; it is a really dangerous issue that we need to address.

“And I think the third issue is that the process of performance management for head teachers is really poor in terms of its understanding of diversity,” Patrick pointed out.

“If governors want to keep female leaders, is there some way we can train them up or teach them how to negotiate to get a good bit of pay, rather than just sitting there on low pay the whole time and then eventually thinking ‘well, I can stay on low pay or go to a bigger school’? I think that is an issue with the gender gap for women and small schools,” she added.

“I know we’re not just talking about head teachers, but if you think of the make-up of those governing bodies. Certainly, in my experience, there has been very little ethnic diversity across the governing body.

“Even when I worked in an area where 70% of the children were non-white British, the governing body was all-white British. So, there is an issue around governance and making sure there is representation at governance levels because I think that may have an impact on recruitment and at senior and head teacher level,” he added.

“It shouldn’t need a crisis to encourage us as a profession to look differently at how we recruit, how we retain, how we support our colleagues and how we develop our colleagues.

“If we don’t understand where the profession is at the moment, then how can we shape it into what we want it to be and enable it to become far more diverse? There is very limited research in terms of why people from diverse backgrounds or backgrounds of protected characteristics might join the profession; we don’t hear a lot about that. And if we don’t know why they’re coming in the first place, then we can’t develop them, can we? Or then encourage others to come and join them,” he added.