From online abuse to artificial intelligence, journalist Nic Paton explores how schools are navigating the promises – and perils – of a hyperconnected world.

Under fire online: protecting school leaders

“Parents being derogatory [towards teachers online] and getting 20 likes if they’re swearing about a member of staff, maybe that’s leaking into real life.

“It’s coming out of the screen and actually into the [school] yard, and perhaps the braveness and boldness seen on social media is leaking into our face-to-face interactions.”

DEBRA WALKER,

NAHT SUNDERLAND BRANCH SECRETARY

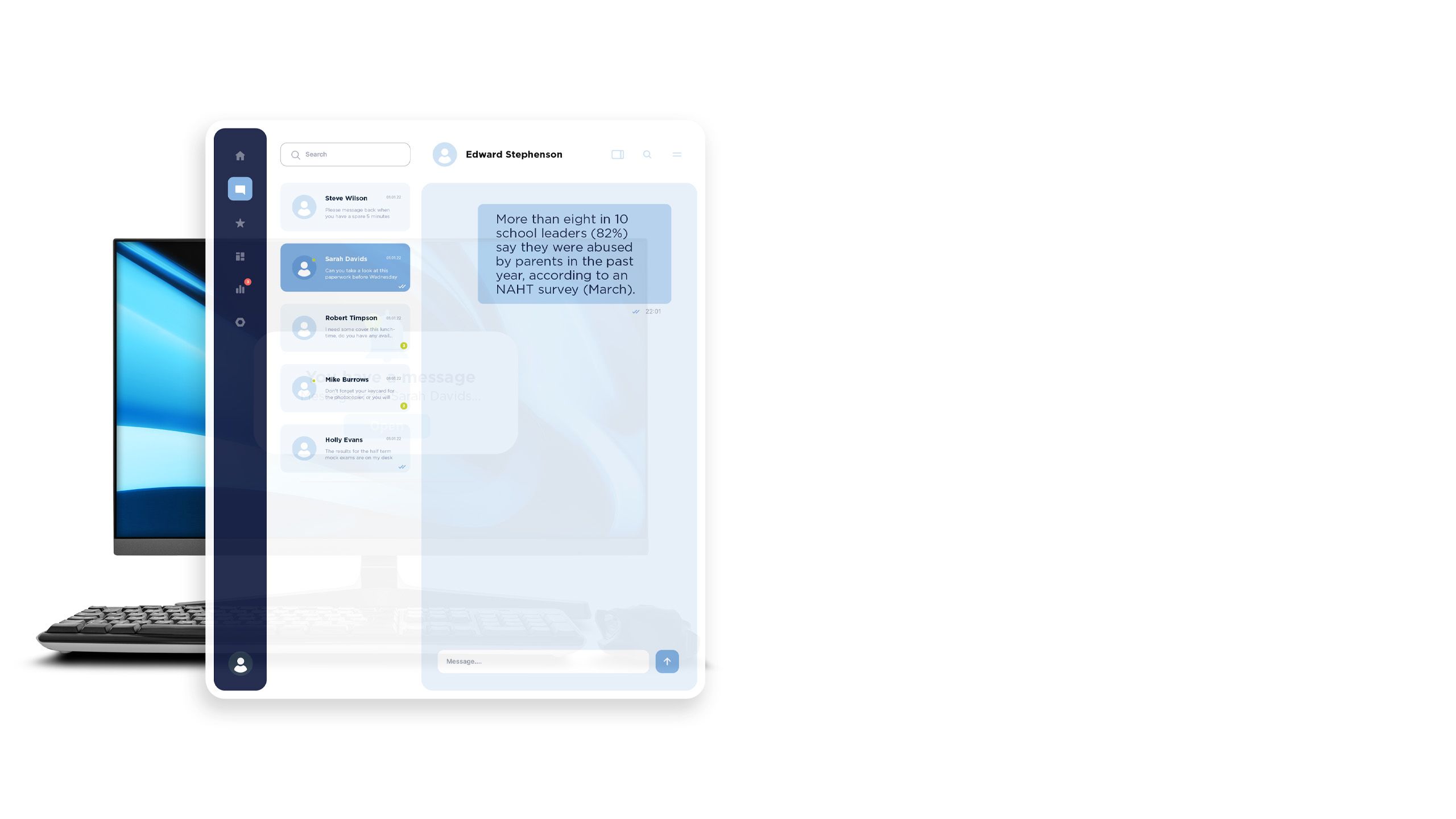

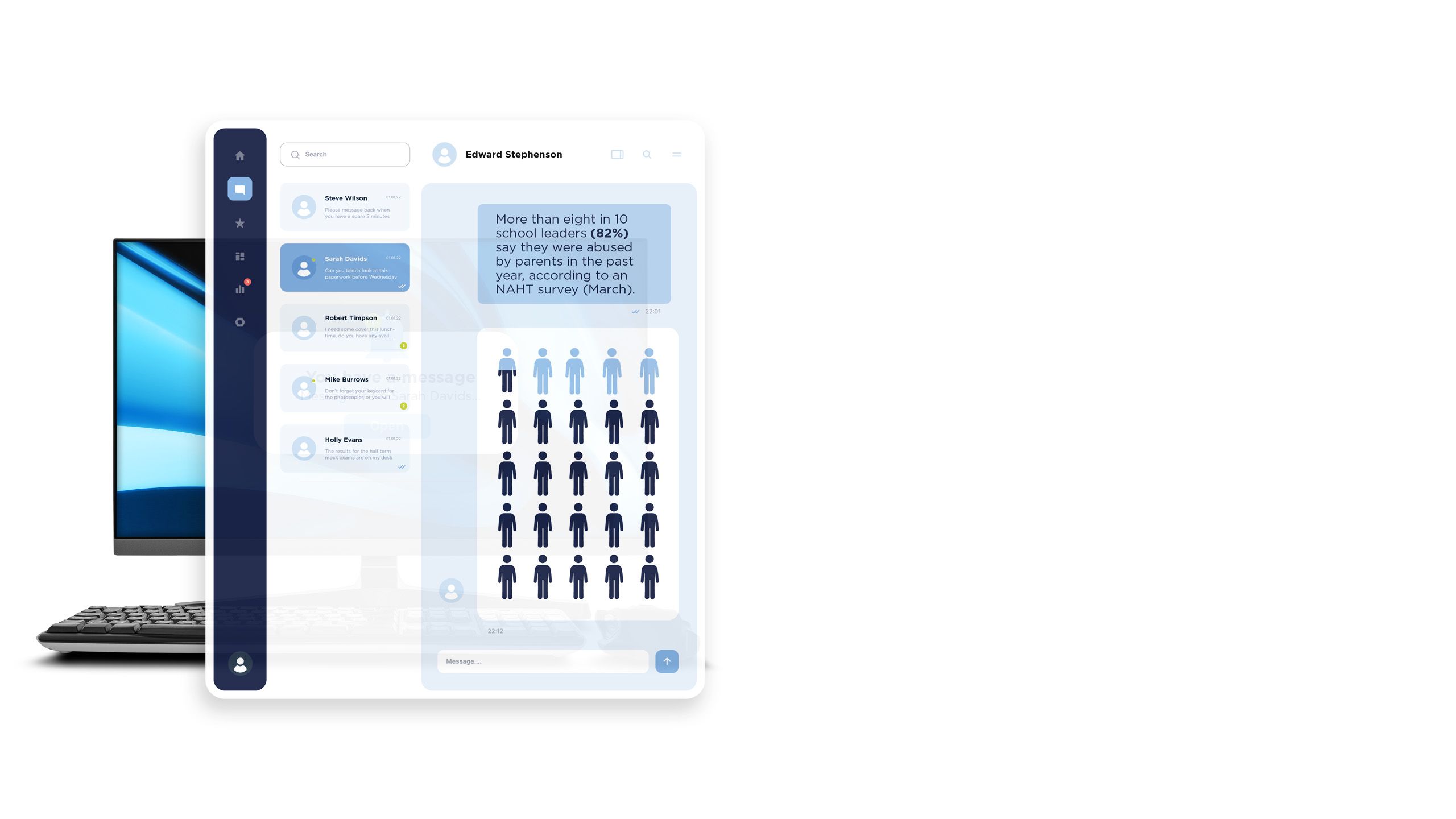

These words – from Debra Walker, NAHT Sunderland branch secretary and regional secretary for the North East, in an interview with Sky News – will undoubtedly resonate with many school leaders. In fact, more than eight out of 10 school leaders (82%) say parents have abused them in the past year, an NAHT survey in March concluded.

While verbal abuse remains the most common form of abuse suffered, online abuse is rising fast (cited by 46%), with the survey of 1,642 school leaders across England, Wales and Northern Ireland exposing widespread reports of trolling on social media and in parent groups on Facebook and WhatsApp, as well as hate campaigns, and harassment and intimidation.

The impact of this can be immense, too. Some school leaders said the abuse had made their lives a misery to the extent that they had considered quitting the profession. It has left some suffering anxiety, depression and panic attacks. As one senior leader put it: “Malicious and vexatious complaints made me want to leave my job and made me ill.”

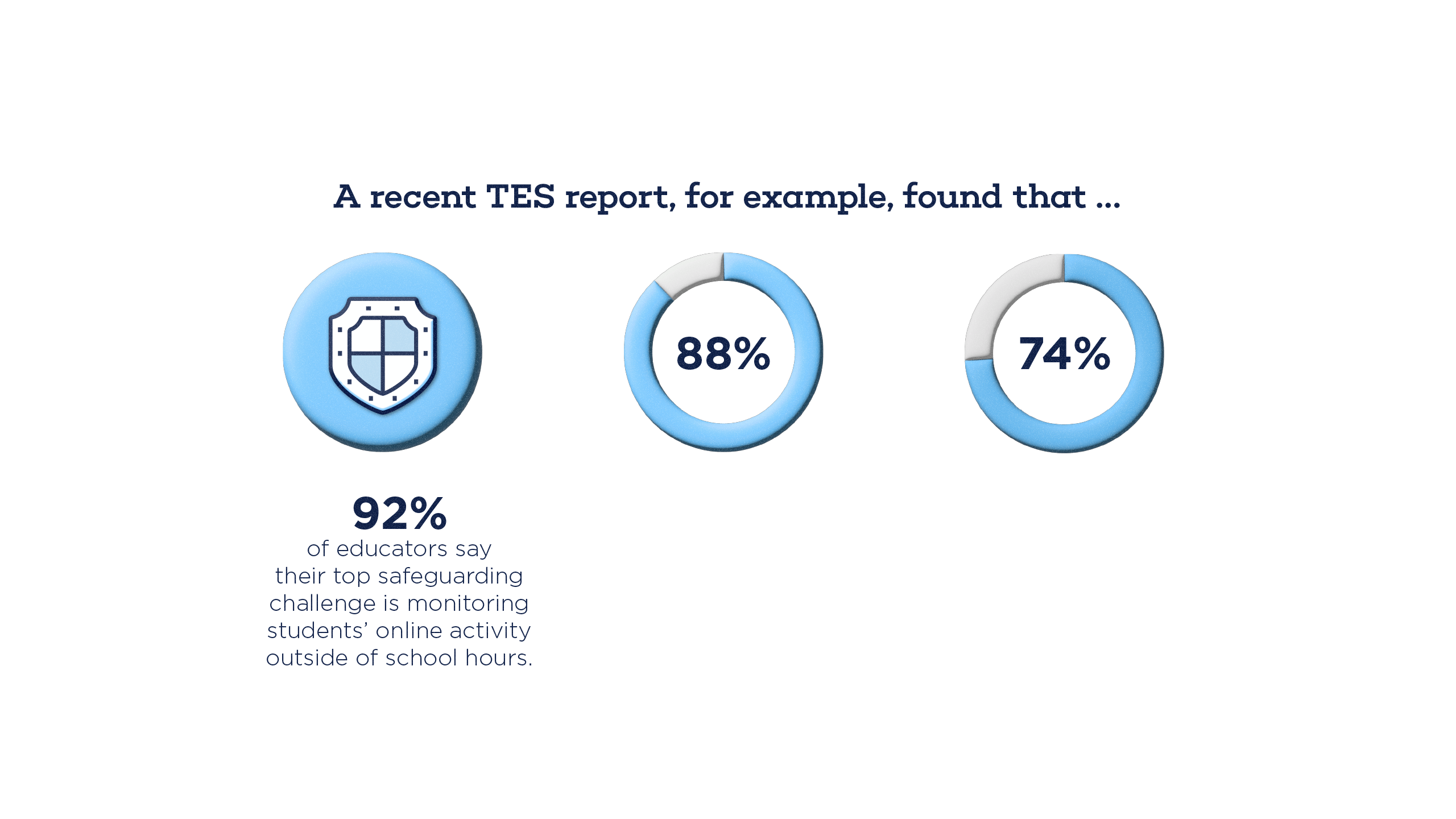

The success of the Netflix drama Adolescence has put a spotlight on the digital safeguarding of children, highlighting the imperative for schools to help children navigate and stay safe in our online world, as well as understand and safely use emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), which this article will also consider.

The restoration in June by Marks & Spencer of its digital shopping portal, after being severely disrupted for six weeks following a cyberattack, has also highlighted the need for schools to be proactive in protecting themselves – their data, their money and their systems – from criminals online.

Yet, arguably, it is the digital safeguarding of staff – protecting teaching staff and school leaders from parental ‘pile-ons’, online abuse and attacks, social media campaigns and even petitions – that is now capturing members’ attention the most, and which many find the most challenging to manage.

Under fire online: protecting school leaders

“Parents being derogatory [towards teachers online] and getting 20 likes if they’re swearing about a member of staff, maybe that’s leaking into real life.

“It’s coming out of the screen and actually into the [school] yard, and perhaps the braveness and boldness seen on social media is leaking into our face-to-face interactions.”

DEBRA WALKER,

NAHT SUNDERLAND BRANCH SECRETARY

These words – from Debra Walker, NAHT Sunderland branch secretary and regional secretary for the North East, in an interview with Sky News – will undoubtedly resonate with many school leaders. In fact, more than eight out of 10 school leaders (82%) say parents have abused them in the past year, an NAHT survey in March concluded.

While verbal abuse remains the most common form of abuse suffered, online abuse is rising fast (cited by 46%), with the survey of 1,642 school leaders across England, Wales and Northern Ireland exposing widespread reports of trolling on social media and in parent groups on Facebook and WhatsApp, as well as hate campaigns, and harassment and intimidation.

The impact of this can be immense, too. Some school leaders said the abuse had made their lives a misery to the extent that they had considered quitting the profession. It has left some suffering anxiety, depression and panic attacks. As one senior leader put it: “Malicious and vexatious complaints made me want to leave my job and made me ill.”

The success of the Netflix drama Adolescence has put a spotlight on the digital safeguarding of children, highlighting the imperative for schools to help children navigate and stay safe in our online world, as well as understand and safely use emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), which this article will also consider.

The restoration in June by Marks & Spencer of its digital shopping portal, after being severely disrupted for six weeks following a cyberattack, has also highlighted the need for schools to be proactive in protecting themselves – their data, their money and their systems – from criminals online.

Yet, arguably, it is the digital safeguarding of staff – protecting teaching staff and school leaders from parental ‘pile-ons’, online abuse and attacks, social media campaigns and even petitions – that is now capturing members’ attention the most, and which many find the most challenging to manage.

Under fire online:

From parental pile‑ons to policy gaps

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

“Schools, school leaders and teachers are increasingly becoming victims of online and social media campaigns, WhatsApp groups and so on,” highlights James Bowen, NAHT assistant general secretary.

“Even parental groups of relatively young children can quickly take off; it just takes one parent to fire something off, and suddenly you can have a pile-on.

“Schools are telling us that they are increasingly dealing with a high level of parental complaints, including a high level of vexatious and disproportionate complaints. That can very easily drift into abuse or online or social media campaigns. As a result of NAHT’s campaigning on this, we are now engaged in talks with the Department for Education (DfE) around trying to find some solutions,” James adds.

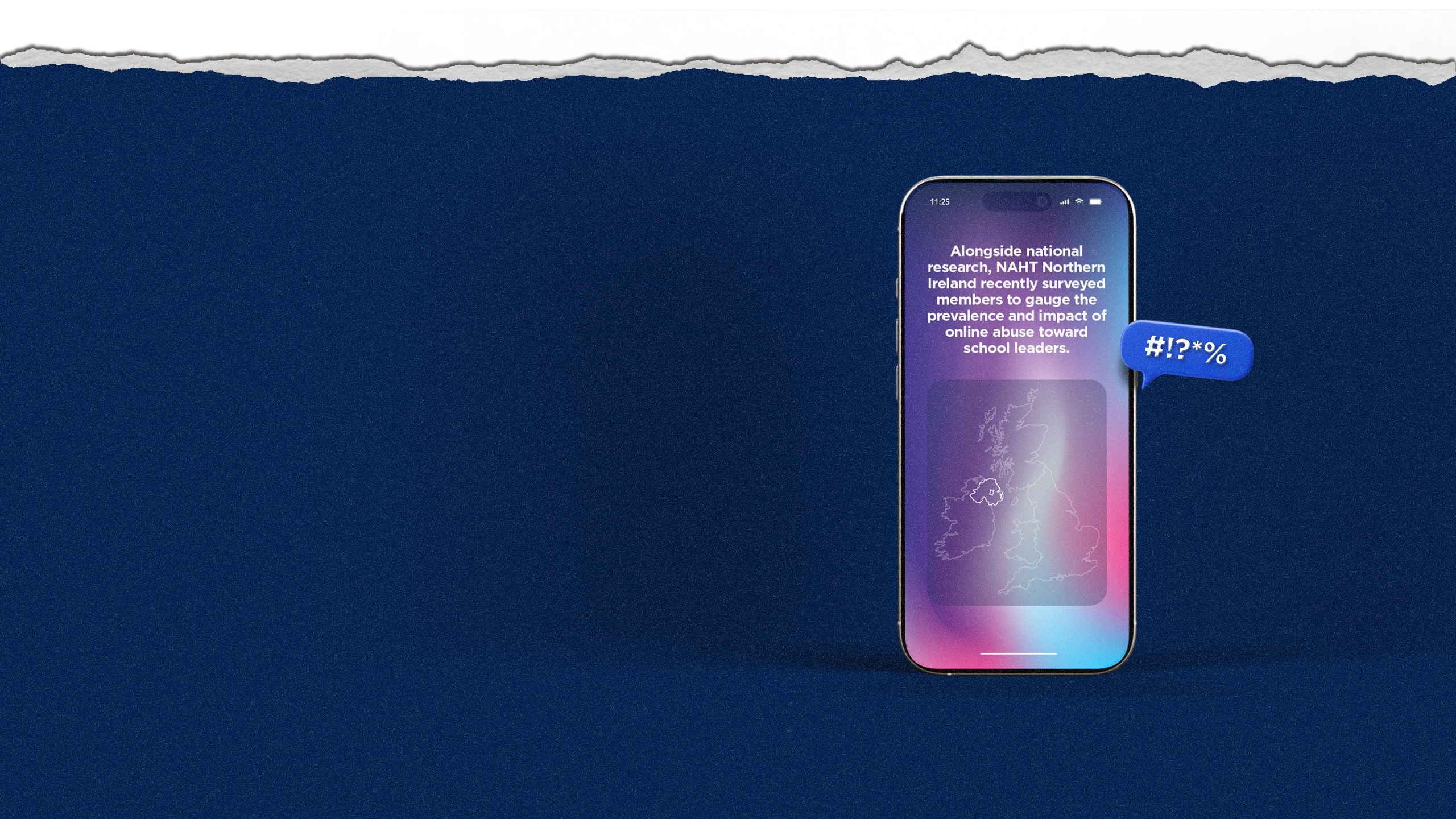

Alongside the national research, NAHT in Northern Ireland recently surveyed members there to gauge the prevalence and impact of online abuse directed at school leaders. The findings, again, were deeply disturbing.

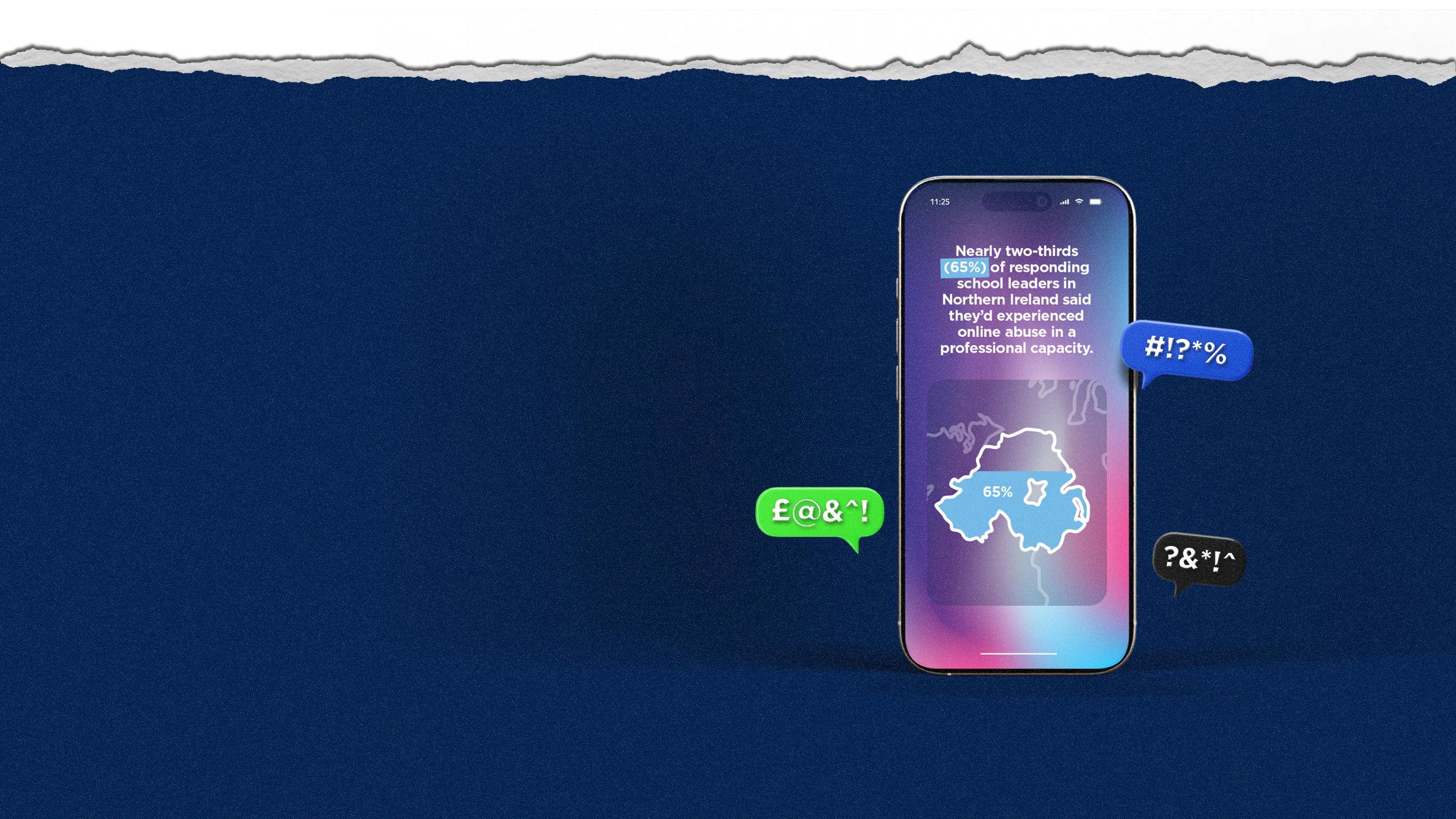

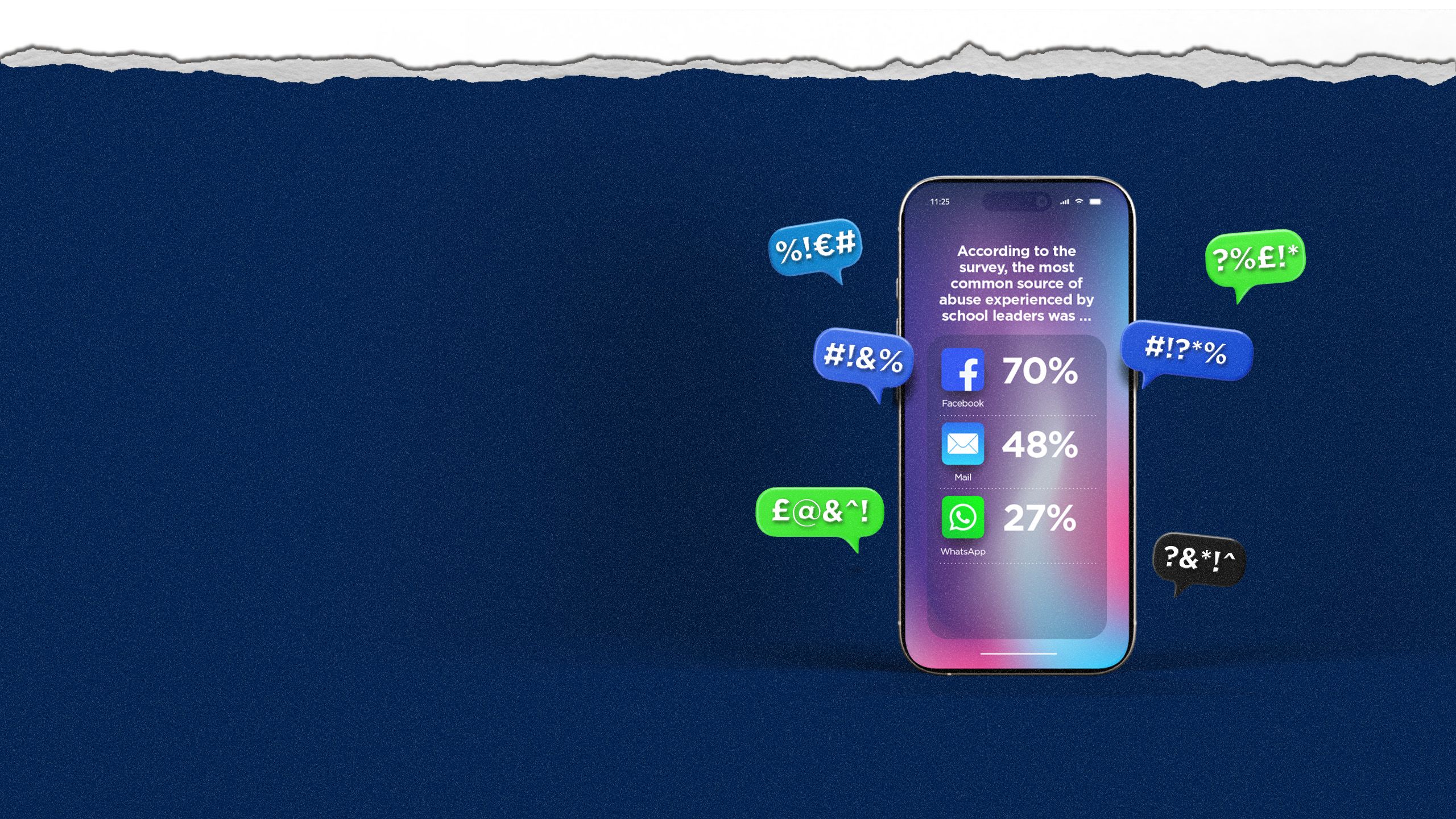

Nearly two-thirds (65%) of school leaders in Northern Ireland who responded said they had been subjected to online abuse in their professional capacity. Facebook was the most common source of abuse (70%), followed by work emails (48%), WhatsApp (27%) and X (formerly Twitter) at 8%.

CHRIS CURRIE,

CHAIR OF NAHT NORTHERN IRELAND’S PRIMARY COMMITTEE

Chris Currie, chair of NAHT Northern Ireland’s Primary Committee, put forward a motion to NAHT Northern Ireland’s annual general meeting last autumn urging the union to lobby the employing authorities “to develop effective processes to address instances of online abuse quickly and to support school leaders in managing the wider misuse of technology in schools”.

DR GRAHAM GAULT,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY

(NORTHERN IRELAND)

NAHT Northern Ireland has indeed been working closely with the Education Authority (EA) to support leaders and develop more robust policies and protocols to safeguard staff against abuse. However, there has been little in the way of meaningful progress, points out Dr Graham Gault, NAHT national secretary (Northern Ireland).

“We had hoped it would mean the EA was developing procedures for school leaders to report when they had been subject to abuse and that some action would be taken. But all it has come up with so far is a list of the reporting procedures for each platform – leaving it up to teachers to report to, say, Facebook, X or whichever platform it might be. For us, that is a total abdication of responsibility,” he says.

Under fire online:

From parental pile‑ons to policy gaps

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

“Schools, school leaders and teachers are increasingly becoming victims of online and social media campaigns, WhatsApp groups and so on,” highlights James Bowen, NAHT assistant general secretary.

“Even parental groups of relatively young children can quickly take off; it just takes one parent to fire something off, and suddenly you can have a pile-on.

“Schools are telling us that they are increasingly dealing with a high level of parental complaints, including a high level of vexatious and disproportionate complaints. That can very easily drift into abuse or online or social media campaigns. As a result of NAHT’s campaigning on this, we are now engaged in talks with the Department for Education (DfE) around trying to find some solutions,” James adds.

Alongside the national research, NAHT in Northern Ireland recently surveyed members there to gauge the prevalence and impact of online abuse directed at school leaders. The findings, again, were deeply disturbing.

Nearly two-thirds (65%) of school leaders in Northern Ireland who responded said they had been subjected to online abuse in their professional capacity. Facebook was the most common source of abuse (70%), followed by work emails (48%), WhatsApp (27%) and X (formerly Twitter) at 8%.

CHRIS CURRIE,

CHAIR OF NAHT NORTHERN IRELAND’S PRIMARY COMMITTEE

Chris Currie, chair of NAHT Northern Ireland’s Primary Committee, put forward a motion to NAHT Northern Ireland’s annual general meeting last autumn urging the union to lobby the employing authorities “to develop effective processes to address instances of online abuse quickly and to support school leaders in managing the wider misuse of technology in schools”.

DR GRAHAM GAULT,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY

(NORTHERN IRELAND)

NAHT Northern Ireland has indeed been working closely with the Education Authority (EA) to support leaders and develop more robust policies and protocols to safeguard staff against abuse. However, there has been little in the way of meaningful progress, points out Dr Graham Gault, NAHT national secretary (Northern Ireland).

“We had hoped it would mean the EA was developing procedures for school leaders to report when they had been subject to abuse and that some action would be taken. But all it has come up with so far is a list of the reporting procedures for each platform – leaving it up to teachers to report to, say, Facebook, X or whichever platform it might be. For us, that is a total abdication of responsibility,” he says.

Under fire online:

Resetting boundaries between parents and schools

LAURA DOEL,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY (WALES)

“We’ve had a number of occasions where we have had to represent members who have found themselves in incredibly challenging situations when it comes to social media,” agrees Laura Doel, NAHT national secretary (Wales).

“A comment about a teacher goes on social media – perhaps initially in a parental WhatsApp group, which appears to be growing in popularity. Before you know it, it’s shared with another group; someone takes a screenshot, and it appears on Facebook or X with the school tagged. From there, it quickly spirals out of control.

“What we try to do in those circumstances is, first, support the individual member. We are also working closely with local authorities to help reset those boundaries. During covid-19, schools and teachers were very available to parents. That culture of teachers always being available or ‘on-call’ has lingered, and when they don’t respond immediately, someone gets on their WhatsApp group and moans. It’s clear that some boundary resetting is needed, along with a restoration of that mutual respect between parents and teachers, which sometimes seems to get lost.

“All schools have appropriate processes in place if parents want to complain – and parents should absolutely complain if they feel something is wrong – but outing somebody on social media for something they have no comeback on is not the way to do it,” Laura adds.

ANGI GIBSON,

NAHT INCOMING PRESIDENT

“Particularly on social media, this has become a serious problem and professional hazard,” says NAHT incoming president Angi Gibson, who is also head teacher at Hadrian Park Primary School in Wallsend.

“It is unacceptable, and I do think we need a consistent zero-tolerance approach. At my school, I will directly contact a parent and ask them to take it down, and depending on how damaging it is, I will get legal advice.

“To me, it comes under safeguarding, so I take very much a zero-tolerance approach. In which other profession, especially public-facing, would it be acceptable for ‘customers’ to have first-line access to that person to complain?

“As school leaders, we are, of course, used to being held accountable, but online abuse and smear campaigns go far beyond that scrutiny. Nobody should have to wake up to threats on WhatsApp groups or abuse just because they work in education. We urgently need protection for staff and consequences for those who put out this abuse,” Angi adds.

Under fire online:

Resetting boundaries between parents and schools

LAURA DOEL,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY (WALES)

“We’ve had a number of occasions where we have had to represent members who have found themselves in incredibly challenging situations when it comes to social media,” agrees Laura Doel, NAHT national secretary (Wales).

“A comment about a teacher goes on social media – perhaps initially in a parental WhatsApp group, which appears to be growing in popularity. Before you know it, it’s shared with another group; someone takes a screenshot, and it appears on Facebook or X with the school tagged. From there, it quickly spirals out of control.

“What we try to do in those circumstances is, first, support the individual member. We are also working closely with local authorities to help reset those boundaries. During covid-19, schools and teachers were very available to parents. That culture of teachers always being available or ‘on-call’ has lingered, and when they don’t respond immediately, someone gets on their WhatsApp group and moans. It’s clear that some boundary resetting is needed, along with a restoration of that mutual respect between parents and teachers, which sometimes seems to get lost.

“All schools have appropriate processes in place if parents want to complain – and parents should absolutely complain if they feel something is wrong – but outing somebody on social media for something they have no comeback on is not the way to do it,” Laura adds.

ANGI GIBSON,

NAHT INCOMING PRESIDENT

“Particularly on social media, this has become a serious problem and professional hazard,” says NAHT incoming president Angi Gibson, who is also head teacher at Hadrian Park Primary School in Wallsend.

“It is unacceptable, and I do think we need a consistent zero-tolerance approach. At my school, I will directly contact a parent and ask them to take it down, and depending on how damaging it is, I will get legal advice.

“To me, it comes under safeguarding, so I take very much a zero-tolerance approach. In which other profession, especially public-facing, would it be acceptable for ‘customers’ to have first-line access to that person to complain?

“As school leaders, we are, of course, used to being held accountable, but online abuse and smear campaigns go far beyond that scrutiny. Nobody should have to wake up to threats on WhatsApp groups or abuse just because they work in education. We urgently need protection for staff and consequences for those who put out this abuse,” Angi adds.

Under fire online:

NAHT’s ‘no excuse for abuse’ campaign and the role of schools

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman agrees this is a difficult issue to manage, let alone resolve, for both school leaders and the wider profession. “It is one of those things where there isn’t an easy lever to pull or button to press to say ‘We can solve this tomorrow!’” he tells Leadership Focus.

“What we are doing, nevertheless, is making sure all of those avenues of parental complaint that are so very difficult to manage are shored up. So, teachers and school leaders don’t get dragged into a melting pot of different complaint mechanisms,” Paul adds.

NAHT is directly supporting members (see below) but is also extending its ‘no excuse for abuse’ campaign to cover the digital sphere as well as physical or face-to-face abuse, as Paul explains.

“This issue fits absolutely perfectly into the ‘no excuse for abuse’ campaign. The abuse and difficulty that members experience online is no different to that they receive face to face,” he says.

“The debate now is that we can’t let this continue any longer – the polarisation, the politics, the awful stuff you now see on X, formerly Twitter, and more and more organisations coming off that. That debate is, I hope, beginning to lead to a change in behaviour.

“What we can do to push that change a little bit quicker is to make sure we have the ability, as school leaders, to be able to write to a parent or call them in and say, ‘We’ve seen you said this about so and so; that simply isn’t acceptable, and if you continue to do so, we will treat it as saying it in public at the school gates’,” Paul adds.

“‘No excuse for abuse’ can be our umbrella into this, and it needs to be backed by zero tolerance,” agrees Angi.

“It is about treating this issue as safeguarding and bullying, and acting in the manner that you would if it involved a child. We have a duty of care to our staff as well as our pupils. Be safe, be strong and follow your policies – NAHT will do everything it can to get the backing from governments, local authorities and trusts,” she adds.

Under fire online:

NAHT’s ‘no excuse for abuse’ campaign and the role of schools

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman agrees this is a difficult issue to manage, let alone resolve, for both school leaders and the wider profession. “It is one of those things where there isn’t an easy lever to pull or button to press to say ‘We can solve this tomorrow!’” he tells Leadership Focus.

“What we are doing, nevertheless, is making sure all of those avenues of parental complaint that are so very difficult to manage are shored up. So, teachers and school leaders don’t get dragged into a melting pot of different complaint mechanisms,” Paul adds.

NAHT is directly supporting members (see below) but is also extending its ‘no excuse for abuse’ campaign to cover the digital sphere as well as physical or face-to-face abuse, as Paul explains.

“This issue fits absolutely perfectly into the ‘no excuse for abuse’ campaign. The abuse and difficulty that members experience online is no different to that they receive face to face,” he says.

“The debate now is that we can’t let this continue any longer – the polarisation, the politics, the awful stuff you now see on X, formerly Twitter, and more and more organisations coming off that. That debate is, I hope, beginning to lead to a change in behaviour.

“What we can do to push that change a little bit quicker is to make sure we have the ability, as school leaders, to be able to write to a parent or call them in and say, ‘We’ve seen you said this about so and so; that simply isn’t acceptable, and if you continue to do so, we will treat it as saying it in public at the school gates’,” Paul adds.

“‘No excuse for abuse’ can be our umbrella into this, and it needs to be backed by zero tolerance,” agrees Angi.

“It is about treating this issue as safeguarding and bullying, and acting in the manner that you would if it involved a child. We have a duty of care to our staff as well as our pupils. Be safe, be strong and follow your policies – NAHT will do everything it can to get the backing from governments, local authorities and trusts,” she adds.

Under fire online:

“You can get parents messaging in the evening, and teachers feeling a responsibility to respond.”

SEAN MCNAMEE,

PRINCIPAL AT ST PAUL’S PRIMARY SCHOOL

Sean McNamee, principal at St Paul’s Primary School in Belfast, freely concedes he and his staff have so far been lucky to escape the worst of parental digital and online abuse. Nevertheless, it is something he is increasingly worried about.

“My fear about social media is how quickly it can become negative, especially in response to a particular incident or issue; suddenly, everything in the school is wrong,” he tells Leadership Focus.

Principal at the school for the past decade, Sean recognises that, more often than not, this lashing out by parents can simply be a symptom of wider frustrations or pressures – especially when (as is the case with his school) it operates in a very socially deprived area.

“In our area, there are high levels of unemployment, high levels of depression, high levels of substance abuse and high levels of mental health issues. People are dealing with an awful lot,” Sean says.

“Then, whenever they come to us, they just spill everything. Sometimes, you can get aggression that is not intended. Sometimes, it can just be verbal abuse. They sometimes just do not have the tools to articulate their feelings without the anger and aggression,” he adds.

The situation is also potentially a legacy of the experience of covid-19 when many schools – and school leaders – allowed themselves to become more digitally accessible to parents and communities, Sean agrees.

“There is an expectation now, and the staff can find it difficult to break that. Now you can get parents messaging in the evening, and teachers are feeling a responsibility to respond,” he says.

“It is about what’s reasonable and what’s not. The difficulty is that even if you put zero-tolerance notices up, you have no way to enforce them. Many of these online groups are outside our jurisdiction anyway,” Sean says.

“We have managed on occasions to get the parent into the school, speak to them and ask them to remove a post, for example. But it is really hard to know what the answer is. I think we need a societal change, and maybe the government needs to do more, too.

“People nowadays expect and want everything, and won’t recognise that sometimes they just can’t have it. It’s not sustainable. We need a reset in some way, shape or form. I just don’t know how that is going to happen – but it does need to be addressed,” Sean adds.

Under fire online:

How NAHT is supporting members

KATE ATKINSON,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY (ADVICE)

From training in how to deal with parental complaints, campaigning, research and advocacy, to access to expert advisers, NAHT is working hard to support members around the safeguarding of staff (and themselves) online, emphasises Kate Atkinson, NAHT national secretary (advice).

“It is fair to say this is a huge problem; it can be really demoralising and insidious when it starts happening. It can break people down because it goes on and on and on; it can really be awful,” she tells Leadership Focus.

“We always recommend members take a staged approach and follow any relevant policies, such as the code of conduct. Because if it does escalate to bigger action, you have an evidence trail; you can show you tried to bring the heat down. You’ve, for instance, tried internal conversations, letters, meetings and legal letters. It is about progressing it, bringing it into your control and having something formal around it, rather than this Wild West.

“Ultimately, however, there is no silver bullet to stop this. We can help you put strategies in place to manage the situation and take the right steps to protect yourself as best you can. But the truth is, these are very difficult cases – for example, some of the worst cases involve anonymous and untraceable accounts. It’s important to remember that an employer has a duty of care to its employees, and that is where the bulk of support to address these issues should come from,” Kate adds.

MALACHY EDWARDS,

NAHT SPECIALIST ADVISER

At the same time, when dealing with frustrated parents, NAHT specialist adviser Malachy Edwards recommends a clear and respectful approach. He suggests saying to parents, “We understand you’re frustrated, but this is the system we have, where we have official channels where you can raise your issues directly with the school. We kindly ask that you show us respect by providing us a reasonable opportunity to address your concerns through the appropriate channels outlined in our school’s policies and procedures.”

“When a school does push back, when it comes into the real world for that person who is complaining, they may recognise that real people are being affected,” he adds.

“However, when you get down to the more persistent and committed serial complainers, sometimes people who appear to enjoy raising complaints habitually, it usually requires the school to step things up in terms of more formal communications. This can include warning that individual about their behaviour and putting a communications plan in place. Schools, when trying to manage a persistent and serial complainant, may also seek advice from their legal provider who can assist in preparing ‘cease and desist’ type of letters.

“At the most serious level – such as threats of violence – the appropriate course of action is to contact the police. In such cases, any warning letters or documented evidence the school has gathered regarding the individual may be valuable to the police, particularly if the matter proceeds to prosecution,” Malachy advises.

Under fire online:

How NAHT is supporting members

KATE ATKINSON,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY (ADVICE)

From training in how to deal with parental complaints, campaigning, research and advocacy, to access to expert advisers, NAHT is working hard to support members around the safeguarding of staff (and themselves) online, emphasises Kate Atkinson, NAHT national secretary (advice).

“It is fair to say this is a huge problem; it can be really demoralising and insidious when it starts happening. It can break people down because it goes on and on and on; it can really be awful,” she tells Leadership Focus.

“We always recommend members take a staged approach and follow any relevant policies, such as the code of conduct. Because if it does escalate to bigger action, you have an evidence trail; you can show you tried to bring the heat down. You’ve, for instance, tried internal conversations, letters, meetings and legal letters. It is about progressing it, bringing it into your control and having something formal around it, rather than this Wild West.

“Ultimately, however, there is no silver bullet to stop this. We can help you put strategies in place to manage the situation and take the right steps to protect yourself as best you can. But the truth is, these are very difficult cases – for example, some of the worst cases involve anonymous and untraceable accounts. It’s important to remember that an employer has a duty of care to its employees, and that is where the bulk of support to address these issues should come from,” Kate adds.

MALACHY EDWARDS,

NAHT SPECIALIST ADVISER

At the same time, when dealing with frustrated parents, NAHT specialist adviser Malachy Edwards recommends a clear and respectful approach. He suggests saying to parents, “We understand you’re frustrated, but this is the system we have, where we have official channels where you can raise your issues directly with the school. We kindly ask that you show us respect by providing us a reasonable opportunity to address your concerns through the appropriate channels outlined in our school’s policies and procedures.”

“When a school does push back, when it comes into the real world for that person who is complaining, they may recognise that real people are being affected,” he adds.

“However, when you get down to the more persistent and committed serial complainers, sometimes people who appear to enjoy raising complaints habitually, it usually requires the school to step things up in terms of more formal communications. This can include warning that individual about their behaviour and putting a communications plan in place. Schools, when trying to manage a persistent and serial complainant, may also seek advice from their legal provider who can assist in preparing ‘cease and desist’ type of letters.

“At the most serious level – such as threats of violence – the appropriate course of action is to contact the police. In such cases, any warning letters or documented evidence the school has gathered regarding the individual may be valuable to the police, particularly if the matter proceeds to prosecution,” Malachy advises.

Useful resources:

Expert advice

Contact one of NAHT’s expert advisers about an issue you’re facing at www.naht.org.uk/expert-advisers

Call us

Ring 0300 30 30 333. The advice line is open 8.30am to 5pm, Monday to Friday (excluding bank holidays).

Learn more

NAHT runs regular training on how to manage parental abuse. Keep an eye online here for course updates.

Free posters

Download NAHT’s free ‘no excuse for abuse’ posters to display in your school and raise awareness.

Pupils and pixels: mobile phones, digital education and AI

Pupils and pixels:

Mobile phones

Last year, the previous Conservative administration published guidance for school leaders on how best to ban mobile phones from classrooms, even though this is already something many schools do in some shape or form. A recent report from the Children’s Commissioner found that 99.8% of primary schools and 90% of secondary schools already have policies in place that limit or restrict the use of mobile phones, which is in line with the DfE’s guidance.

“There have been many calls, from politicians and celebrities, to ban mobile phones,” James points out. “But the reality is that many children and young people use mobile phones outside of school whether we like it or not. As educators, we need to help children navigate the digital landscape – teaching children who have devices how to be safe online and educating them about things like the ‘manosphere’ and Andrew Tate and so on,” James adds.

SARAH HANNAFIN,

NAHT HEAD OF POLICY (PRACTICE AND RESEARCH)

“NAHT members have been dealing with these issues for a long time, and so there is a sense that the government’s guidance is just catching up,” agrees Sarah Hannafin, NAHT head of policy (practice and research), also emphasising that the government’s guidance is non-statutory.

“Our national executive discussed the use of mobile phones in school in June and made a clear distinction between the approach in primary and secondary schools.

“The executive was clear that there is no need for most children in primary schools to have access to a mobile phone during the school day. A ban across all primary schools takes the pressure off schools and gives clarity to parents.

“Of course, there will be rare circumstances where pupils need access to a mobile phone – like monitoring sugar levels – and schools will, of course, facilitate that even with a ban. And parents of children who travel to and from school on their own might want them to have a phone for safety, but that doesn’t need to be a smartphone.

“With older students, at secondary, there needs to be more flexibility for leaders to develop a policy and strategy that is right for their school and community. Any wholesale ban will probably take some investment – you may, for example, need lockers or pouches.

“There is also the question of how to bring pupils and parents on board when implementing or changing school policy. School leaders are well aware of the issues, and most already have policies in place,” Sarah adds.

Especially in more rural parts of the country, such as Wales, it can be important that children have at least some access to phones, emphasises Laura.

“In some more rural schools – where children may travel a long way to get to school – the feedback from parents is strong that they want their children to have a phone for that journey.

“Some schools are reporting a huge uptake in social media activity; for example, filming of fights, and influencers or even teachers being followed. In response, there is a need for a more rigid approach to mobile phone use.

“Schools need to have support in putting guidance in place, and the local authority (the 22 local authorities in Wales) and parents need to work with schools to enforce that policy. For example, if a school says, ‘You can bring your phones into school, but you have to put them in a plastic pouch at reception and then collect them at the end of the day’, parents are supportive of that and work with the school to make it work.

“Mobile phones are not going away, and they can be hugely valuable, so we don’t just want to demonise them. It is about restricting the use of mobile phones during the school day and encouraging schools to have those healthy debates with families, with children and with staff,” Laura adds.

Pupils and pixels:

Digital education and AI

A further element within this is educating children about how best to use, understand and benefit from emerging new digital technologies, especially generative AI systems.

As Tim Clarke, head teacher at Cornerstone Church of England Primary School in Hampshire, highlights below, new technologies and tools are already transforming how schools develop and deliver learning, bringing significant benefits for both teachers and children.

Yet, as James also emphasises, schools have a critical role to play as educators – not only in teaching children the benefits of these new technologies but also their limitations and potential pitfalls – whether that’s harmful content or the risks around accuracy and plagiarism that can come with over-reliance on technology such as AI.

NAHT, he points out, has published guidance for members on the use of AI in education, and May’s national Annual Conference also debated the perils of AI-generated imagery and ‘deepfakes’, among other issues.

“I think when it comes to the whole education piece – educating children on what to do when they come across something inappropriate, who to speak to, how to report it and determining the difference between fact and fiction online – schools can, and should, have an important role to play there,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“Our job as educators has to be to prepare young people for the digital world they’re going into when they leave school,” James adds.

“AI does present opportunities when it comes to learning. We are massively positive about AI. I don’t think we can hide away from it; it is just going to get bigger. So, we need to embrace that,” agrees Angi. “But AI also raises real issues and concerns – especially around data privacy and workload.

“We want school leaders to innovate, but we also want clarity and a safeguarding promise – that what we adopt won’t create extra safeguarding concerns or add to the workload. There is a risk that AI could be sold to schools as a quick fix without sufficient consideration of ethics, safety or the impact on pupils.

“Yes, AI is a superb tool for saving time. But is it correct? Is it ethically correct? Is there a bias? Are we data breaching? Those are all things children – and staff to an extent – need to learn and understand. We should embrace it, but we should do so with caution. Also, we can’t do this alone. We need the government, industry and communities to match this commitment,” Angi adds.

“The ability for young people to be critical thinkers – to be questioning, to be able to identify good and bad sources of information – is a vitally important skill to learn in terms of the education we can give young people, especially in the context of new technologies,” agrees Paul in conclusion.

“Teachers and school leaders should feel free – and confident – to be educating children about these issues, knowing that parents will also take part in that education as well. It is all about understanding what is acceptable online and what is not within that larger debate about the virtual space.

“What the government has got to do, as it begins to look at the curriculum, is give that time and space for teachers to be able to develop those skills, those learning tools, for young people. This is a journey, really, that all of us are only beginning on,” Paul adds.

Pupils and pixels:

Mobile phones

Last year, the previous Conservative administration published guidance for school leaders on how best to ban mobile phones from classrooms, even though this is already something many schools do in some shape or form. A recent report from the Children’s Commissioner found that 99.8% of primary schools and 90% of secondary schools already have policies in place that limit or restrict the use of mobile phones, which is in line with the DfE’s guidance.

“There have been many calls, from politicians and celebrities, to ban mobile phones,” James points out. “But the reality is that many children and young people use mobile phones outside of school whether we like it or not. As educators, we need to help children navigate the digital landscape – teaching children who have devices how to be safe online and educating them about things like the ‘manosphere’ and Andrew Tate and so on,” James adds.

SARAH HANNAFIN,

NAHT HEAD OF POLICY (PRACTICE AND RESEARCH)

“NAHT members have been dealing with these issues for a long time, and so there is a sense that the government’s guidance is just catching up,” agrees Sarah Hannafin, NAHT head of policy (practice and research), also emphasising that the government’s guidance is non-statutory.

“Our national executive discussed the use of mobile phones in school in June and made a clear distinction between the approach in primary and secondary schools.

“The executive was clear that there is no need for most children in primary schools to have access to a mobile phone during the school day. A ban across all primary schools takes the pressure off schools and gives clarity to parents.

“Of course, there will be rare circumstances where pupils need access to a mobile phone – like monitoring sugar levels – and schools will, of course, facilitate that even with a ban. And parents of children who travel to and from school on their own might want them to have a phone for safety, but that doesn’t need to be a smartphone.

“With older students, at secondary, there needs to be more flexibility for leaders to develop a policy and strategy that is right for their school and community. Any wholesale ban will probably take some investment – you may, for example, need lockers or pouches.

“There is also the question of how to bring pupils and parents on board when implementing or changing school policy. School leaders are well aware of the issues, and most already have policies in place,” Sarah adds.

Especially in more rural parts of the country, such as Wales, it can be important that children have at least some access to phones, emphasises Laura.

“In some more rural schools – where children may travel a long way to get to school – the feedback from parents is strong that they want their children to have a phone for that journey.

“Some schools are reporting a huge uptake in social media activity; for example, filming of fights, and influencers or even teachers being followed. In response, there is a need for a more rigid approach to mobile phone use.

“Schools need to have support in putting guidance in place, and the local authority (the 22 local authorities in Wales) and parents need to work with schools to enforce that policy. For example, if a school says, ‘You can bring your phones into school, but you have to put them in a plastic pouch at reception and then collect them at the end of the day’, parents are supportive of that and work with the school to make it work.

“Mobile phones are not going away, and they can be hugely valuable, so we don’t just want to demonise them. It is about restricting the use of mobile phones during the school day and encouraging schools to have those healthy debates with families, with children and with staff,” Laura adds.

Pupils and pixels:

Digital education and AI

A further element within this is educating children about how best to use, understand and benefit from emerging new digital technologies, especially generative AI systems.

As Tim Clarke, head teacher at Cornerstone Church of England Primary School in Hampshire, highlights below, new technologies and tools are already transforming how schools develop and deliver learning, bringing significant benefits for both teachers and children.

Yet, as James also emphasises, schools have a critical role to play as educators – not only in teaching children the benefits of these new technologies but also their limitations and potential pitfalls – whether that’s harmful content or the risks around accuracy and plagiarism that can come with over-reliance on technology such as AI.

NAHT, he points out, has published guidance for members on the use of AI in education, and May’s national Annual Conference also debated the perils of AI-generated imagery and ‘deepfakes’, among other issues.

“I think when it comes to the whole education piece – educating children on what to do when they come across something inappropriate, who to speak to, how to report it and determining the difference between fact and fiction online – schools can, and should, have an important role to play there,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“Our job as educators has to be to prepare young people for the digital world they’re going into when they leave school,” James adds.

“AI does present opportunities when it comes to learning. We are massively positive about AI. I don’t think we can hide away from it; it is just going to get bigger. So, we need to embrace that,” agrees Angi. “But AI also raises real issues and concerns – especially around data privacy and workload.

“We want school leaders to innovate, but we also want clarity and a safeguarding promise – that what we adopt won’t create extra safeguarding concerns or add to the workload. There is a risk that AI could be sold to schools as a quick fix without sufficient consideration of ethics, safety or the impact on pupils.

“Yes, AI is a superb tool for saving time. But is it correct? Is it ethically correct? Is there a bias? Are we data breaching? Those are all things children – and staff to an extent – need to learn and understand. We should embrace it, but we should do so with caution. Also, we can’t do this alone. We need the government, industry and communities to match this commitment,” Angi adds.

“The ability for young people to be critical thinkers – to be questioning, to be able to identify good and bad sources of information – is a vitally important skill to learn in terms of the education we can give young people, especially in the context of new technologies,” agrees Paul in conclusion.

“Teachers and school leaders should feel free – and confident – to be educating children about these issues, knowing that parents will also take part in that education as well. It is all about understanding what is acceptable online and what is not within that larger debate about the virtual space.

“What the government has got to do, as it begins to look at the curriculum, is give that time and space for teachers to be able to develop those skills, those learning tools, for young people. This is a journey, really, that all of us are only beginning on,” Paul adds.

Pupils and pixels:

“The key thing is always to go back to the ‘why?’”

TIM CLARKE,

HEAD TEACHER AT CORNERSTONE CHURCH OF ENGLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL

From just 27 children learning in temporary huts when it first opened in 2013, Cornerstone Church of England Primary School in Whiteley, Hampshire, has grown to 399 pupils and, says head teacher Tim Clarke, has ambitions to grow even further.

He highlights that the embrace and use of technology, both by staff and pupils, has been a key part of this success story and is something he feels passionate about.

The school is a Microsoft Showcase School (part of Hampshire EdTech Hub), has been developing and expanding its use of generative AI over the past two years, has been part of an Ofsted research project in the use of technology in schools, and has led training for school leaders, special educational needs coordinators and teachers.

Via its ‘Digital Cornerstone case studies Sway’, the school showcases a range of case studies created by teaching and support staff across the primary school. The AI page on the school’s website shares its policy, an article written by Tim and colleagues for The Chartered College of Teaching’s termly journal, Impact, and a range of resources. Tim (along with deputy head teacher Laura Rodbourne) has presented on the role that schools can play in ‘growing responsible and purposeful digital citizens’. Its digital vision, resources and case studies are all bundled together on a bespoke ‘Digital Cornerstone’ section of the school’s website.

“The use of technology removes barriers of time and space both for staff and our key stage pupils,” Tim tells Leadership Focus. Nevertheless, he emphasises that technology should always complement – rather than simply replace – conventional learning or pedagogy.

“We make the point that 90% of the learning the children do is still in books, on paper and with pens. What we want to do is teach the children that technology is a tool to be used purposefully and responsibly when needed, like a ruler or a pair of scissors, rather than just because it is exciting,” Tim explains.

This is very much the case, too, with the use of generative AI. Yes, teaching staff are increasingly using AI to help create resources, but the key word here is ‘help’. “It is trying to say to the children, ‘It is not about technology doing the work for us; it is how it supplements and supports that learning’. AI is, or should be, just another tool,” Tim says.

He also points out that when Ofsted inspected the school in November 2024, the fact that all the documentation he and his team needed was readily accessible within the school’s Microsoft 365 cloud-based infrastructure made the process much less workload-intensive. “All staff had access to the collaborative documents – and any document Ofsted wanted to see, we could bring up as a live version in 10 to 20 seconds.”

Used well, these technologies can be hugely beneficial in terms of assisting inclusive learning, he highlights, citing the example of a year six teacher who was teaching an Edgar Allan Poe poem.

“We had a child in there with an education, health and care plan and a reading age of about seven who would not have been able to access the poem,” Tim says.

“The teacher, prior to the lesson, put the poem into Microsoft Copilot and asked it to simplify the poem for a seven-year-old reader, which it did in seconds. She then tweaked it, made sure she was happy with it and put it into another online tool called Widgit, which dual-coded it and gave most of the words pictures. The whole process took only a few minutes.

“The teacher then gave the child a copy that he could read and understand, which did wonders for his sense of inclusion, well-being and belonging. When the class was discussing the poem, he could join in because he had been able to access the text,” Tim adds.

Equally, for children with English as an additional language, tools such as Microsoft’s Immersive Reader (or its equivalent via other providers) can be a great way to allow children to listen to a text, either in English or their first language, and begin the learning process.

“The key thing is always to go back to the ‘why?’. There has to be a genuine purpose, not just because you can or because it is the latest new thing. It is also about slowly developing and embedding new aspects. Back in 2020, for example, we were doing very little of this work with ‘PedTech’, but we just add a few more innovations to solve problems or enhance practice each year,” Tim explains.

“Moreover, if staff don’t receive training and you don’t revisit this professional development, new practices won’t stick. For example, the case studies we have developed – sharing and celebrating these examples – are a really good resource.

“With AI, a key priority is to have an agreed and detailed policy first. This ensures that leadership can provide clarity of governance while enabling staff to be creative and innovative with new uses, purposes and solutions. We’ve updated our policy at least 12 or 13 times in just the last year alone because it is constantly evolving. In our case, AI is always either for enhancing teaching and learning or supporting and managing workload,” Tim adds.

Breached and exposed: cyber threats facing schools

Cybersecurity – “A primary school we had to rescue, their final bill came to £19,500.”

Think it could never happen to you? A recent Home Office and Department for Science, Innovation and Technology poll found that, of 250 primary and 240 secondary schools surveyed, 44% and 60%, respectively, had experienced some form of cybersecurity breach or attack in the previous 12 months.

The fact this is higher than the 43% of businesses that also reported being targeted by scammers, phishers, hackers and ransomware illustrates – if more red warning lights were needed – the scale of the potential cyber threat facing schools and head teachers.

MATTHEW SETCHELL,

CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER AT CONCERO

To a degree, the fact schools are so on the front line when it comes to cybersecurity should not be that surprising, Matthew Setchell, chief technology officer of IT firm Concero, told James Bowen for a recent ‘The School Leadership’ podcast.

“If you think about it, schools are quite large networks. There are very few businesses that will have as many people – a large secondary school, for example, might have more than 1,000 pupils and maybe 200 staff. Businesses of that kind of size are few and far between,” he said, with schools potentially handling large budgets, especially at the beginning of the school year.

“Also, you have this situation where schools obviously can’t afford to employ their own cybersecurity teams, like businesses can, to protect their systems,” he added.

If anything, in fact, the figures above may even be something of an understatement, given that year-on-year figures published by the government in April last year estimated that as many as 71% of secondary schools and 52% of primary schools had been affected by cyberattacks in the previous 12 months.

“We have this situation where schools are utilising more and more online tools, and they’re opening up their systems for connectivity to allow systems to talk inside their networks with hardware,” said Matthew.

“So, for example, cashless catering, door-entry systems, and opening up for CCTV – stuff like that. We’re also making it ever easier for people to work everywhere and anywhere and access everything outside the school that they used to only [be able to] access internally,” he added.

“I’ve literally been sat in an office at a trust where the chief financial officer got an email from the chief executive officer (CEO) asking her to approve an attached invoice. Now, they both happened to be sitting with me in a meeting, and the CEO hadn’t sent that email.

“They [the scammers] had gone through emails and found a previous supplier, and they’d just changed the sort code and the account number on the invoice. The school might have just paid it, and the scammers would have got a £50,000 invoice paid directly to them. Because both the CEO and CFO were sat next to me, it was an interesting conversation,” Matthew explained.

What, James asked, can schools and school leaders do about this growing threat?

Moving your data over to the cloud and ensuring you have physical back-ups (and back-ups of the back-ups) are both good ideas, Matthew advised. “Lots of schools are currently in a hybrid model, so they’ll have servers on-site and data in Google or Microsoft, such as Google Drive, OneDrive, SharePoint or whatever.

“They’re working across both, which means you’ve got to protect both, you’ve got to pay to licence both, and you’ve got to manage both. By going fully cloud, on a simple level, if you have no servers in your school, they can’t be hacked. It’s as simple as that,” said Matthew.

It is also about recognising that, more often than not, the weakest link is not the technology itself but the people using it. Education, awareness, communication and training are therefore all key, with Matthew advising that working with Secure Schools can be a good starting point.

“I also imagine there’s a fair few people going, ‘This all sounds very expensive. We have no money, and our budgets are all stuffed. Is this going to cost us thousands and thousands of pounds to do properly?’. So, I guess my question is, will it?” James asked.

“Probably, if I’m honest. But you need to put it up against the cost of if you don’t,” Matthew replied, albeit emphasising he wanted to see the cost of properly protecting schools – as a national infrastructure – become covered by the government.

“To give you an idea, a primary school we had to rescue, their final bill came to £19,500. It’s not one of those things that you can fix without spending money, unfortunately.

“But you wouldn’t have a building without fire extinguishers. Now, you may never use fire extinguishers, but more schools have been affected by cyberattacks than are affected by fires. So, yes, it will cost you money, but it is money you need to spend,” Matthew added.

You can find The School Leadership Podcast wherever you listen to podcasts – where you can also rate, review and subscribe.

Cybersecurity – “A primary school we had to rescue, their final bill came to £19,500.”

Think it could never happen to you? A recent Home Office and Department for Science, Innovation and Technology poll found that, of 250 primary and 240 secondary schools surveyed, 44% and 60%, respectively, had experienced some form of cybersecurity breach or attack in the previous 12 months.

The fact this is higher than the 43% of businesses that also reported being targeted by scammers, phishers, hackers and ransomware illustrates – if more red warning lights were needed – the scale of the potential cyber threat facing schools and head teachers.

MATTHEW SETCHELL,

CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER AT CONCERO

To a degree, the fact schools are so on the front line when it comes to cybersecurity should not be that surprising, Matthew Setchell, chief technology officer of IT firm Concero, told James Bowen for a recent ‘The School Leadership’ podcast.

“If you think about it, schools are quite large networks. There are very few businesses that will have as many people – a large secondary school, for example, might have more than 1,000 pupils and maybe 200 staff. Businesses of that kind of size are few and far between,” he said, with schools potentially handling large budgets, especially at the beginning of the school year.

“Also, you have this situation where schools obviously can’t afford to employ their own cybersecurity teams, like businesses can, to protect their systems,” he added.

If anything, in fact, the figures above may even be something of an understatement, given that year-on-year figures published by the government in April last year estimated that as many as 71% of secondary schools and 52% of primary schools had been affected by cyberattacks in the previous 12 months.

“We have this situation where schools are utilising more and more online tools, and they’re opening up their systems for connectivity to allow systems to talk inside their networks with hardware,” said Matthew.

“So, for example, cashless catering, door-entry systems, and opening up for CCTV – stuff like that. We’re also making it ever easier for people to work everywhere and anywhere and access everything outside the school that they used to only [be able to] access internally,” he added.

“I’ve literally been sat in an office at a trust where the chief financial officer got an email from the chief executive officer (CEO) asking her to approve an attached invoice. Now, they both happened to be sitting with me in a meeting, and the CEO hadn’t sent that email.

“They [the scammers] had gone through emails and found a previous supplier, and they’d just changed the sort code and the account number on the invoice. The school might have just paid it, and the scammers would have got a £50,000 invoice paid directly to them. Because both the CEO and CFO were sat next to me, it was an interesting conversation,” Matthew explained.

What, James asked, can schools and school leaders do about this growing threat?

Moving your data over to the cloud and ensuring you have physical back-ups (and back-ups of the back-ups) are both good ideas, Matthew advised. “Lots of schools are currently in a hybrid model, so they’ll have servers on-site and data in Google or Microsoft, such as Google Drive, OneDrive, SharePoint or whatever.

“They’re working across both, which means you’ve got to protect both, you’ve got to pay to licence both, and you’ve got to manage both. By going fully cloud, on a simple level, if you have no servers in your school, they can’t be hacked. It’s as simple as that,” said Matthew.

It is also about recognising that, more often than not, the weakest link is not the technology itself but the people using it. Education, awareness, communication and training are therefore all key, with Matthew advising that working with Secure Schools can be a good starting point.

“I also imagine there’s a fair few people going, ‘This all sounds very expensive. We have no money, and our budgets are all stuffed. Is this going to cost us thousands and thousands of pounds to do properly?’. So, I guess my question is, will it?” James asked.

“Probably, if I’m honest. But you need to put it up against the cost of if you don’t,” Matthew replied, albeit emphasising he wanted to see the cost of properly protecting schools – as a national infrastructure – become covered by the government.

“To give you an idea, a primary school we had to rescue, their final bill came to £19,500. It’s not one of those things that you can fix without spending money, unfortunately.

“But you wouldn’t have a building without fire extinguishers. Now, you may never use fire extinguishers, but more schools have been affected by cyberattacks than are affected by fires. So, yes, it will cost you money, but it is money you need to spend,” Matthew added.

You can find The School Leadership Podcast wherever you listen to podcasts – where you can also rate, review and subscribe.