Leadership Focus journalist Nic Paton speaks to school leaders about the extra financial costs of covid-19 and how they've tried to manage the financial hit.

For education, there is the growing worry about the cost of the pandemic in terms of lost and disrupted learning and the impact on attainment, progress and social mobility for a whole generation of young people, especially for those children in our most deprived communities. But for schools and school leaders, there is another increasingly pressing concern emerging: the expanding pools of red now appearing on schools’ balance sheets as the extra financial costs of covid-19 begin to make themselves felt across what was already, even before the pandemic, a financially stressed education system.

From personal protective equipment (PPE) and hand sanitiser through to extra cleaning, school meals, ventilation and signage; from the additional costs of providing cover for those off sick or self-isolating through to lost income from lettings or reduced nursery care, there is a legion of costs from covid-19 mounting for schools. And they continue to mount as, of course, we’re not out of the pandemic yet and probably won’t be for many months to come.

IAN HARTWRIGHT,

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISOR

As Ian Hartwright, NAHT senior policy advisor, puts it to Leadership Focus: “There are all the costs of keeping your school safe and covid-19 secure. There’s the cost of supply, which is huge in some cases, and then there is lost income which – for many schools with significant lettings income from things such as halls, gyms, swimming pools, IT facilities or pitches – can amount to tens or even hundreds of thousands of pounds a year.”

To gauge the scale of the problem, NAHT surveyed 2,044 school leaders over a fortnight from the end of last September to find out what they felt were their most immediate cost pressures as a direct result of the pandemic. Its findings were stark.

During the first month of the autumn term, mean average additional exceptional costs as a direct result of covid-19 were £8,017, with a large number of schools reporting costs of more than £10,000, and a few in excess of £100,000.

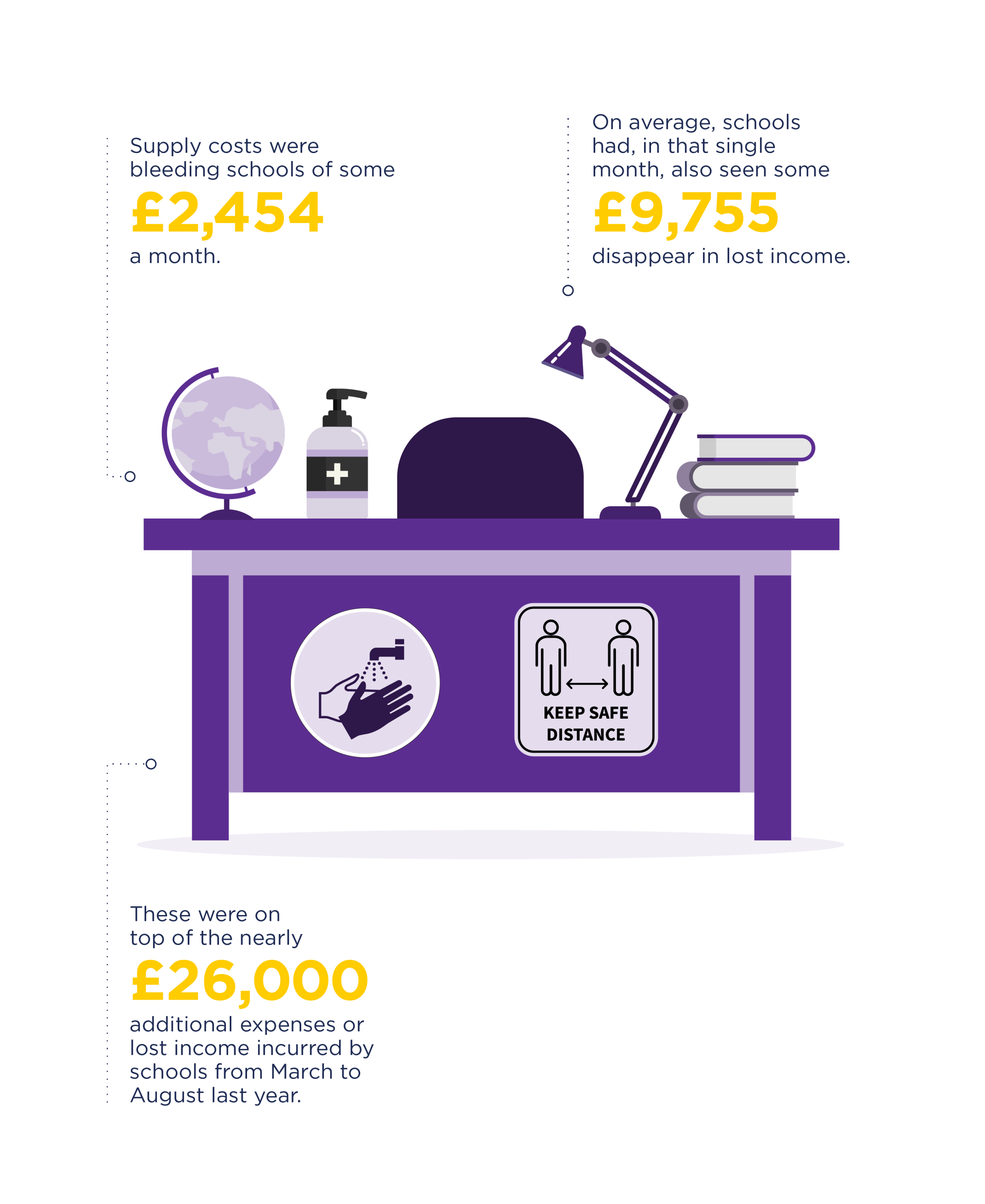

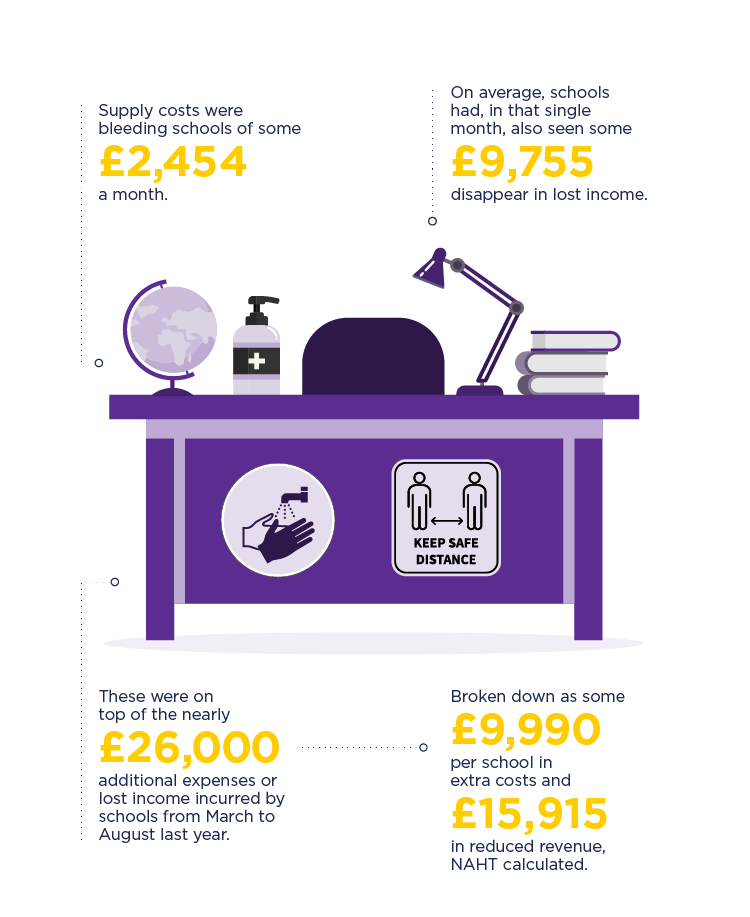

Supply costs were bleeding schools of some £2,454 a month. On average, schools had, in that single month, also seen some £9,755 disappear in lost income. However, the figure was much higher than that for many. These were on top of the nearly £26,000 additional expenses or lost income incurred by schools from March to August last year, broken down as some £9,990 per school in extra costs and £15,915 in reduced revenue, NAHT calculated.

The survey also highlighted that while the Department for Education (DfE) has put in place an ‘exceptional costs’ reimbursement scheme, this has been narrow and limited in scope. For instance, not including extra expenditure required to make a school ‘covid-19 secure’. This is a concern that has been forcefully echoed by the Education Policy Institute.

Furthermore, all these additional financial pressures are eating into budgets (for 2020/21) that were set, agreed and planned before the crisis. Schools are, therefore, using money that should have been allocated for pupils’ education.

As NAHT’s report states: “School leaders are skilled at eking out budgets. But no school leader could have predicted or budgeted for the costs of a global pandemic. Most schools have insufficient fiscal headroom to manage and offset even relatively modest covid-19-related spending.

“The impact of covid-19 falls unevenly. Individual schools’ additional costs are dependent on a wide range of contextual factors, including, for example, deprivation. The nation’s children have already suffered because of the pandemic. Each school must now be fully supported in meeting the cost of covid-19.”

Then there is the mental and emotional pressure this all adds onto the shoulders of school leaders, which is on top of everything else that has come with navigating schools through perhaps the toughest crisis in a century.

For education, there is the growing worry about the cost of the pandemic in terms of lost and disrupted learning and the impact on attainment, progress and social mobility for a whole generation of young people, especially for those children in our most deprived communities. But for schools and school leaders, there is another increasingly pressing concern emerging: the expanding pools of red now appearing on schools’ balance sheets as the extra financial costs of covid-19 begin to make themselves felt across what was already, even before the pandemic, a financially stressed education system.

From personal protective equipment (PPE) and hand sanitiser through to extra cleaning, school meals, ventilation and signage; from the additional costs of providing cover for those off sick or self-isolating through to lost income from lettings or reduced nursery care, there is a legion of costs from covid-19 mounting for schools. And they continue to mount as, of course, we’re not out of the pandemic yet and probably won’t be for many months to come.

IAN HARTWRIGHT,

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISOR

As Ian Hartwright, NAHT senior policy advisor, puts it to Leadership Focus: “There are all the costs of keeping your school safe and covid-19 secure. There’s the cost of supply, which is huge in some cases, and then there is lost income which – for many schools with significant lettings income from things such as halls, gyms, swimming pools, IT facilities or pitches – can amount to tens or even hundreds of thousands of pounds a year.”

To gauge the scale of the problem, NAHT surveyed 2,044 school leaders over a fortnight from the end of last September to find out what they felt were their most immediate cost pressures as a direct result of the pandemic. Its findings were stark.

During the first month of the autumn term, mean average additional exceptional costs as a direct result of covid-19 were £8,017, with a large number of schools reporting costs of more than £10,000, and a few in excess of £100,000.

Supply costs were bleeding schools of some £2,454 a month. On average, schools had, in that single month, also seen some £9,755 disappear in lost income. However, the figure was much higher than that for many. These were on top of the nearly £26,000 additional expenses or lost income incurred by schools from March to August last year, broken down as some £9,990 per school in extra costs and £15,915 in reduced revenue, NAHT calculated.

The survey also highlighted that while the Department for Education (DfE) has put in place an ‘exceptional costs’ reimbursement scheme, this has been narrow and limited in scope. For instance, not including extra expenditure required to make a school ‘covid-19 secure’. This is a concern that has been forcefully echoed by the Education Policy Institute.

Furthermore, all these additional financial pressures are eating into budgets (for 2020/21) that were set, agreed and planned before the crisis. Schools are, therefore, using money that should have been allocated for pupils’ education.

As NAHT’s report states: “School leaders are skilled at eking out budgets. But no school leader could have predicted or budgeted for the costs of a global pandemic. Most schools have insufficient fiscal headroom to manage and offset even relatively modest covid-19-related spending.

“The impact of covid-19 falls unevenly. Individual schools’ additional costs are dependent on a wide range of contextual factors, including, for example, deprivation. The nation’s children have already suffered because of the pandemic. Each school must now be fully supported in meeting the cost of covid-19.”

Then there is the mental and emotional pressure this all adds onto the shoulders of school leaders, which is on top of everything else that has come with navigating schools through perhaps the toughest crisis in a century.

RACHEL YOUNGER,

NAHT’S SCHOOL BUSINESS LEADERS’ SECTOR COUNCIL CHAIR

As Rachel Younger, business manager at St Nicholas Church of England Primary School in Blackpool and NAHT’s school business leaders’ sector council chair, highlights: “We all have extra pressure. Specifically for school business leaders, we have all the same things we have to do normally – invoices still need to be paid, monthly accounts still need to be reconciled, and contractors and service providers still need to be managed – but now with so much extra on top of that.”

“We’ve put in place extra cleaning hours during the day as well, and I know from talking to other [school business leaders] in Blackpool, they’ve done the same,” says Rachel.

This is an impact felt across the country, in the devolved nations as well as England.

LAURA DOEL,

NAHT CYMRU DIRECTOR

“We have a significant number of schools now going into a deficit budget through no fault of their own. They knew that they would be going into a deficit budget, but the mechanisms to manage that are unavailable to them. That has caused a lot of stress and anxiety for members,” says NAHT Cymru director Laura Doel.

Although the Welsh Government has set up the ‘local government single emergency hardship fund’, this is not something ring-fenced for education. Instead, it is a pot of money for local authorities to use across the piece, she points out.

“So, you have everybody bidding for money from the same fund. Local authorities have seen their income/revenue streams frozen – leisure centres, car parking charges, and so on – so they have been really stretched for money as well.

“As a local authority finance director, you’re not going to let schools dip into that when you are also dipping into it to keep everything else going. The reality is it is very difficult for schools to dip into that money,” she says.

HELENA MACORMAC,

NAHT(NI) DIRECTOR

“There has been some confusion, and concern, among members in Northern Ireland about what will and won’t be reimbursed; there is a lot of uncertainty,” says Helena Macormac, NAHT(NI) director.

“There is a significant number of schools in Northern Ireland that are already in the red. School leaders see that the pandemic will be an inevitable extra cost on top of everything else, and the fear is that they are going to be plunged even further into deficit as a result of this.

“There is so much day-to-day firefighting going on at the moment that some of the long-term issues around funding, which were there even before the pandemic, haven’t come to the fore yet. But, obviously, they will, and people are worried,” she adds.

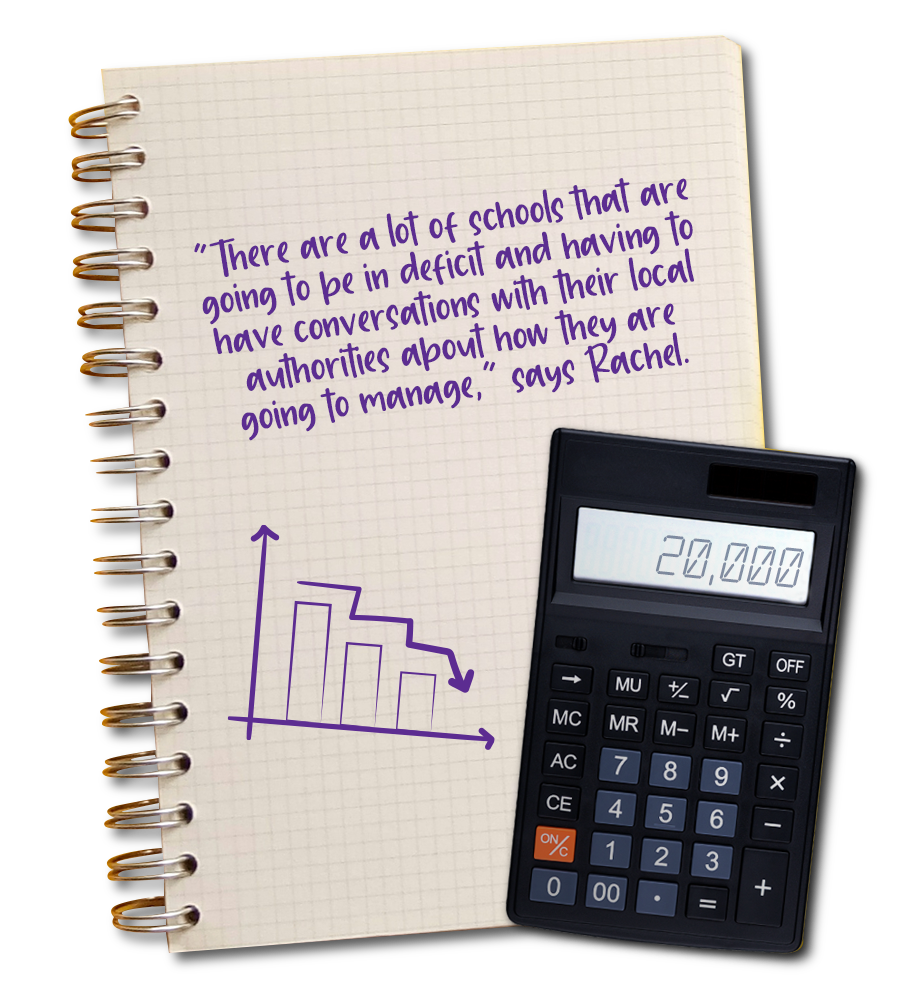

So, where does this all leave schools? Rachel, for one, highlights that spiralling deficits risk making the whole sector much more financially insecure going forward.

“There are a lot of schools that are going to be in deficit and having to have conversations with their local authorities about how they are going to manage. And academies are going to need to be having the same sorts of conversations. We need to do something now to try and stop things getting out of hand,” she says.

“I would also like an acknowledgement that, actually, schools can’t afford all the extra costs they have to pay. Some sort of extra financial top-up would be the best way forward, and not one that we have to wait for until the next financial settlement is agreed. We need it imminently,” Rachel adds.

“It is not schools trying to get more money; schools just want to get back what they have spent extra on to get through this pandemic. It is going to be a massive issue within a lot of schools’ budgets,” agrees Ian.

And Laura highlights an extra, yet equally important, concern within all this. “If a school is in a financial deficit, that is grounds, technically, for disciplinary action against the school leader; a school leader could be hauled over the coals, even if there would be a strong defence, given the circumstances.

“That is another additional headache and pressure on school leaders that they really don’t need right now,” she adds.

RACHEL YOUNGER,

NAHT’S SCHOOL BUSINESS LEADERS’ SECTOR COUNCIL CHAIR

As Rachel Younger, business manager at St Nicholas Church of England Primary School in Blackpool and NAHT’s school business leaders’ sector council chair, highlights: “We all have extra pressure. Specifically for school business leaders, we have all the same things we have to do normally – invoices still need to be paid, monthly accounts still need to be reconciled, and contractors and service providers still need to be managed – but now with so much extra on top of that.”

“We’ve put in place extra cleaning hours during the day as well, and I know from talking to other [school business leaders] in Blackpool, they’ve done the same,” says Rachel.

This is an impact felt across the country, in the devolved nations as well as England.

LAURA DOEL,

NAHT CYMRU DIRECTOR

“We have a significant number of schools now going into a deficit budget through no fault of their own. They knew that they would be going into a deficit budget, but the mechanisms to manage that are unavailable to them. That has caused a lot of stress and anxiety for members,” says NAHT Cymru director Laura Doel.

Although the Welsh Government has set up the ‘local government single emergency hardship fund’, this is not something ring-fenced for education. Instead, it is a pot of money for local authorities to use across the piece, she points out.

“So, you have everybody bidding for money from the same fund. Local authorities have seen their income/revenue streams frozen – leisure centres, car parking charges, and so on – so they have been really stretched for money as well.

“As a local authority finance director, you’re not going to let schools dip into that when you are also dipping into it to keep everything else going. The reality is it is very difficult for schools to dip into that money,” she says.

HELENA MACORMAC,

NAHT(NI) DIRECTOR

“There has been some confusion, and concern, among members in Northern Ireland about what will and won’t be reimbursed; there is a lot of uncertainty,” says Helena Macormac, NAHT(NI) director.

“There is a significant number of schools in Northern Ireland that are already in the red. School leaders see that the pandemic will be an inevitable extra cost on top of everything else, and the fear is that they are going to be plunged even further into deficit as a result of this.

“There is so much day-to-day firefighting going on at the moment that some of the long-term issues around funding, which were there even before the pandemic, haven’t come to the fore yet. But, obviously, they will, and people are worried,” she adds.

So, where does this all leave schools? Rachel, for one, highlights that spiralling deficits risk making the whole sector much more financially insecure going forward.

“There are a lot of schools that are going to be in deficit and having to have conversations with their local authorities about how they are going to manage. And academies are going to need to be having the same sorts of conversations. We need to do something now to try and stop things getting out of hand,” she says.

“I would also like an acknowledgement that, actually, schools can’t afford all the extra costs they have to pay. Some sort of extra financial top-up would be the best way forward, and not one that we have to wait for until the next financial settlement is agreed. We need it imminently,” Rachel adds.

“It is not schools trying to get more money; schools just want to get back what they have spent extra on to get through this pandemic. It is going to be a massive issue within a lot of schools’ budgets,” agrees Ian.

And Laura highlights an extra, yet equally important, concern within all this. “If a school is in a financial deficit, that is grounds, technically, for disciplinary action against the school leader; a school leader could be hauled over the coals, even if there would be a strong defence, given the circumstances.

“That is another additional headache and pressure on school leaders that they really don’t need right now,” she adds.

RUNNING ON EMPTY

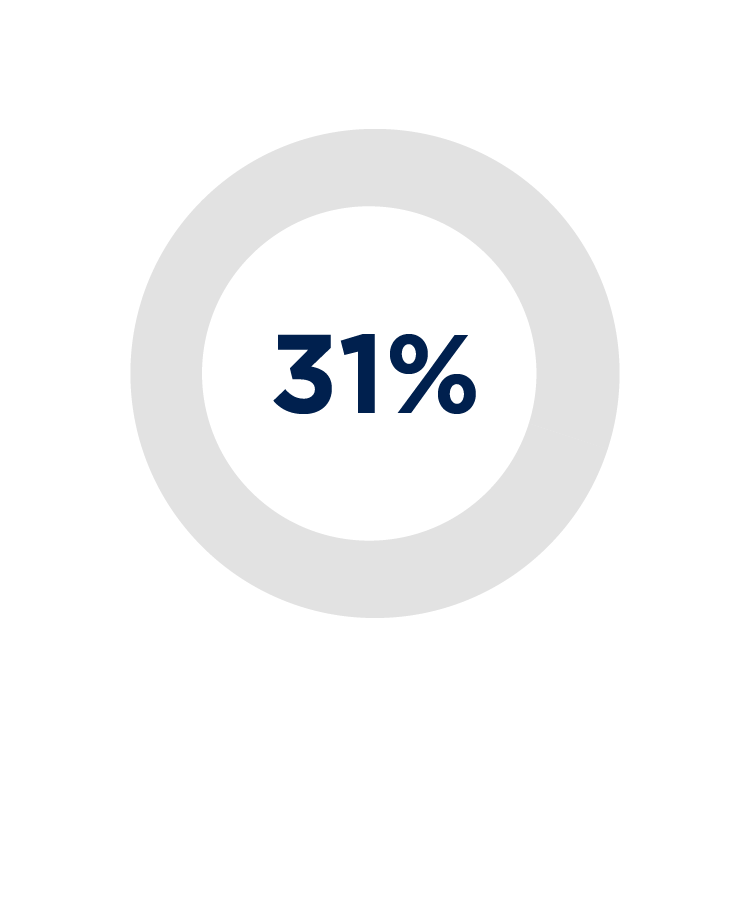

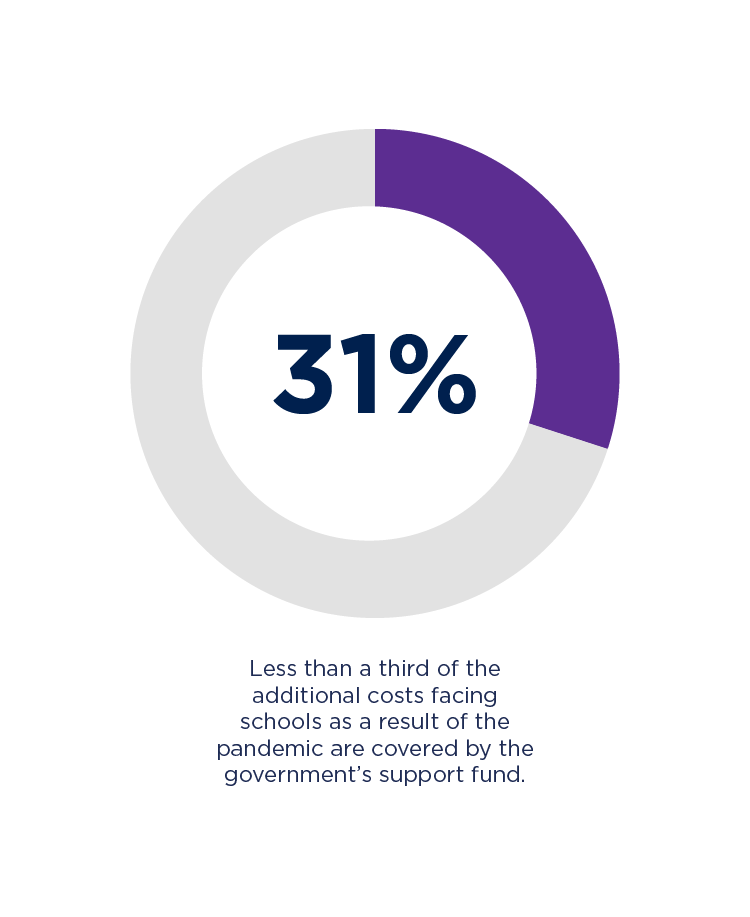

A hard-hitting analysis from the Education Policy Institute (EPI) has broadly echoed the findings of NAHT’s autumn survey when it comes to gauging the financial impact of covid-19 on schools. Its report, ‘Assessing covid-19 cost pressures on England’s schools’, published in December, concluded that less than a third (31%) of the additional costs facing schools as a result of the pandemic are covered by the government’s support fund.

The analysis, based on responses from more than 700 schools, covering March to November 2020, was supported by NAHT and ASCL.

Almost all schools reported extra expenditure on PPE and cleaning supplies. A large majority faced additional costs from signage, digital equipment and handwashing facilities.

Schools had also spent more on teaching staff, which was expected to increase further in the months ahead.

The average shortfall schools were facing amounted to £40 per pupil, and it could mean many schools will be forced to make savings elsewhere, it warned.

In addition to increased costs, nine out of 10 schools had seen their incomes fall, with more affluent schools seeing the biggest reductions. These schools were also more likely to miss out on voluntary contributions or income derived from hiring out their facilities, the EPI said.

Despite these pressures, a quarter of primary schools and half of secondary schools reported making some savings, largely on utilities.

Worryingly, the report concluded that more than half (57%) of all schools were now using their reserves to meet covid-19-related costs. A similar proportion of schools (48% of primaries and 50% of secondaries) did not expect to have balanced their budget by the end of the year, which would represent an increase of around 10 percentage points on 2018/19.

You can download the full report here.

SALLY THOMSON IS THE SCHOOL BUSINESS MANAGER AT ST EDWARD’S CHURCH OF ENGLAND VA PRIMARY SCHOOL IN ROMFORD, ESSEX. THE THREE-FORM ENTRY SCHOOL HAS APPROXIMATELY 600 CHILDREN AS WELL AS A NURSERY. A COMBINATION OF LOSS OF LETTINGS INCOME, WRAPAROUND CARE AND EXTRA NURSERY HOURS MEANS ITS TOTAL LOSS OF REVENUE THIS YEAR WILL BE AROUND £78,500.

“We have, of course, had a lot of extra day-to-day costs for things, such as cleaning and extra supply cover for when staff have been isolating. We have been reimbursed for some of that, and we are expecting another payment this term. Our local authority, London Borough of Havering, has been quite supportive and has been refunding percentages of service level agreement costs, which has helped slightly.

“However, where we have been hit is through losses associated with self-generated income from lettings, our wraparound care and extra nursery hours. All these things have reduced significantly because of the pandemic.

“On extra nursery hours, parents are entitled to 15 hours’ free nursery care or can qualify for 30 hours’, with those who don’t qualify able to pay for the extra 15 hours’. However, because of covid-19 and parents working from home or perhaps not wanting to send their children in, we are losing a lot of that income. Whereas we’d normally expect this to be about £24,000, it’s been more in the region of £13,000.

“Our wraparound care facility is significantly down on numbers this year too because parents’ working patterns have changed and the school has been closed on and off. Based on 2019/20, we would have expected income of £100,000 this year, but we will probably only receive in the region of £25,000. We have partially offset this using the furlough scheme, but it will still be in the region of a £36,000 loss.

“We have also been hit by our loss of income from lettings. We have a swimming pool here, and we normally let that. It is a big source of income; we put a lot of that back into the costs of running the pool.

“When we started the last financial year, we put in a budget that was in deficit. We’ve been quite prudent and careful throughout the year with how we’ve spent money. We’ve set up an extra cost centre in our budget where we put in anything extra. But for the next financial year, we’re going to be starting the budget, probably, still without any lettings income.

“The amount of funding we receive only covers the bare necessities, and we are not an extravagant school, as our benchmarking shows. But we are not left with enough to improve the condition and appearance of the school. We have the most wonderful new head teacher, who has so many positive and forward-thinking ideas and plans for the school, but, now, not enough funding to carry them out.”

AVRIL STOCKLEY IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF THE WILLIAM HOGARTH SCHOOL IN CHISWICK, WEST LONDON, A ONE-FORM ENTRY PRIMARY SCHOOL WITH APPROXIMATELY 210 PUPILS. IN THE PAST YEAR, THE SCHOOL HAS GONE FROM HAVING A TIGHTLY BALANCED BUDGET TO BEING IN A DEFICIT POSITION AS A RESULT OF COVID-19 COSTS AND FACING THE STARK REALITY OF HAVING TO MAKE IMPOSSIBLY TOUGH DECISIONS.

“It has been absolutely devastating financially. Before covid-19, we had a whole-school restructure and were in a position where we could see some financial stability and security – a position that would give us a good platform to grow from and enable us to focus on some key areas of learning and curriculum enrichment. And then covid-19 happened.

“We did it safely: risk assessments were robust, and the staff felt confident. We also developed our remote learning package; right from day one of the first lockdown, we had learning on the website for children.

“But the thing that has really pulled the rug out from underneath us has been school meals. During the first lockdown, we kept our kitchen open to provide hot meals for the children of key workers and vulnerable children. We also thought we would be helping the local covid-19 effort by allowing our kitchen to be used to provide meals for neighbouring schools in Hillingdon, Slough, Hounslow and Hammersmith.

“It turns out this was a huge mistake, and it has contributed massively to the deficit we now face. It has been awful for us financially. My monthly charge to Chartwells – which, remember, is part of the massively profitable Compass group – is £7,800. That’s nothing to do with the food, but simply to service its finance costs, management charges and staff costs. So, by the end of the first lockdown, my bill was more than £30,000. If I had closed my kitchen, like some schools near us did, I could have saved money.

“We’ve been allowed to claim £25,000 under the government’s reimbursement scheme. But, between ensuring social distancing is robust, increasing cleaning schedules and making sure teachers have the technology they need to deliver effective remote learning, we are looking at costs in the region of £45,000 – that’s significantly more than we can claim.

“In the first wave, our claim was £19,000, and we only recovered £9,000 – that was without even claiming for all of the school meal invoices or the invoice from Chartwells. During the most recent lockdown, we decided we could no longer afford to support the local community or wider London as we had before, so we have taken the upsetting decision to close our kitchen for the period of lockdown. But even with our kitchen now closed, catering costs are still going to cost the school £4,500 a month.

“I’m looking at the budget and thinking about the fact that I have a deficit to carry forward now that I didn’t have before.

“Does this mean I need to consider the possibility of making school staff redundant so that the school’s budget can be used to prop up a catering company – an external commercial enterprise at that? I’m going to have to do something about it; I can’t just ignore it. And that seems to me really wrong because how does that put children first, especially when they have already missed out on so much?”

SARAH COX IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF BROOK INFANT SCHOOL AND NURSERY IN CRAWLEY, WEST SUSSEX. THE TWO-FORM ENTRY SCHOOL HAS 170 CHILDREN, AND THE 54-PLACE NURSERY IS PRIVATELY RUN, SO IT GENERATES AN INCOME. THE SCHOOL ALSO PROVIDES WRAPAROUND CARE.

“We have, of course, had a financial impact from covid-19. You could see it coming, and we have had to plan for it. It was clear we were going to have to get into the realms of PPE, hand sanitiser and so on, which will continue to be the case for many months.

“But I do feel the government stepped up. In that first, initial lockdown when we, of course, didn’t know it was coming, its scheme of putting in your expenses and pretty much meeting them has, for us, worked. It has met what we put in.

“For exceptional expenses, the reimbursement scheme had a separate section where you could put in for additional things, and it either said yes or no, which I think is fair. For example, we got a portable cabin on-site because we had to strip back the classrooms, and we did not have enough room to store the stuff coming out.

“My business manager looked at the budget before we submitted it to the local authority in May, and we tweaked it in light of covid-19 suddenly appearing in March. So, now, our bottom line is actually realistic. We do have increased costs and loss of earnings on the one hand, but there are, actually, some decreased costs too. For example, we’ve made some savings in areas such as staff cover that had been predicted but wasn’t already booked (we did obviously honour all booked cover) – we’ve been able to cover it in different ways going forward.

“We’ve adapted our budget to fit. Where we’ve struggled – for example, where wraparound care hasn’t happened or where, as we did during the first lockdown, we offered it for free to key workers – we simply spoke to the staff and have been able to redirect them. For example, one of our cleaners couldn’t carry on; it was linked to covid-19, but they decided to resign. We decided not to take on another cleaner at that point. Instead, we spoke to the team, and the staff were more than happy to be redirected. Similarly, with one of our wraparound care staff members, instead of using the furlough scheme (which we felt was really for those who could not survive without it), we redirected them into a teaching assistant role. So, it has been just about using money in a different way.

“We have tried, where we can, to carry on with our long-term development plan too, and some of this has actually been accelerated by covid-19. For example, we have moved to voice-over-internet phone calling. By making that upgrade – yes, there was an outlay – there will now be savings going forward. We’ve been able to carry out some outdoor developments too because we’ve had fewer children in school.

“We knew we needed to update our IT systems, and we went over to Microsoft just before this all happened, but, again, covid-19 has helped us to embed that change. So, it is not necessarily that covid-19 has enabled things, but we have not allowed covid-19 to stop us from doing things. We’ve really tried to be proactive, and I think it has saved us from bleeding money.

“Having said that, I do recognise everyone is in a different situation. I’m in a school that didn’t start with a deficit budget and brings in an income. Another school might have been in deficit, and therefore this period would have been horrendous; I equally know of some schools that are sitting on a £50,000 bottom line they weren’t expecting to have. I do feel we also need to say there is some positive from this; I think that would help everybody’s mental health.”

THOMAS BREWER IS THE HEAD TEACHER AT BATHAMPTON PRIMARY SCHOOL IN BATH, WHICH HAS NEARLY 200 PUPILS.

“The covid-19 pandemic has had a detrimental effect on our school’s budget for the following reasons:

- Cleaning – we have had to purchase significant additional cleaning materials. Some of these materials we have been able to reclaim. However, to date, we have spent an additional £1,929 on cleaning

- Staff laptops/equipment – our school had just purchased new desktop computers for the classrooms. When we knew school was closing, I purchased laptops for teachers so that we could begin to deliver online learning. This was a necessity, but it wasn’t in our budget, so it’s an additional cost

- Wraparound care income – we had a healthy wraparound care club making a good profit for the school. We’ve been grateful that we have been able to furlough those four staff members each time, but our income is down for both 2019/20 and 2020/21 significantly.

“There was an expectation that schools should 'honour' any financial commitments made to supply teachers who may have been used had it not been for the pandemic. We honoured this because, morally, it was the right thing to do for all our supply teachers who would not be able to claim furlough.

“We’ve made a loss on catering to support our catering company through the loss of meals too.

“We’re really grateful for all the money we’ve been able to reclaim, such as some cleaning materials, additional electricity, gas and sewerage, PPE and additional signage.

“However, the true cost of covid-19 for us means we are worse off in 2019/20 by £7,545 and by a projected worst-case scenario of £57,000 in 2020/21.”

MARY* IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF A NURSERY SCHOOL IN HERTFORDSHIRE THAT HAS AROUND 246 CHILDREN.

“We’ve lost nearly £250,000 through a combination of lost income from wraparound care, the cost of additional cleaning and PPE, and the cost of additional laptops for staff. And we’ve not been allowed to claim back a single penny of our covid-19 costs.

“Originally, we thought we were fine to put in a claim. ‘Absolutely, you’re a school’, we were told. But then it was ‘sorry, actually, no you don’t qualify’. People in our local authority have been talking to people at the Department for Education. Some are going ‘yes’, and others are saying ‘absolutely not’.

“I have 60 staff on permanent school contracts, and now it’s like ‘can we manage without some of them?’. We’re looking at redundancies, which we’ve never had to do before. But then, at the same time, we have no funding in the pot to enable us to pay for redundancies either.

“Another complication is that even if we start that organisational change straight away, by the time we’ve gone through all the processes and consultations, it’s not going to be happening before this coming September. Then, once September comes in, even if it is all agreed, the staff will be on full protected pay for nine months and half-the-difference protected pay for a further nine months.

“So, we’ll be two-and-a-half years down the line before the school really gets to see any benefit from making those changes. And by then, of course, hopefully, everyone will have had the vaccines, and we’ll be going ‘hang on a minute. We need these hours back’.”

*name has been anonymised

SIMON* IS A SCHOOL BUSINESS LEADER FOR A LARGE SECONDARY SCHOOL IN LONDON WITH APPROXIMATELY 2,000 PUPILS.

“For us, our loss of income from lettings for the autumn and spring terms is looking likely to be in the region of £45,000. On top of that, additional day cleaners to clean our cafeteria between breaks and dinner times and our classrooms where bubbles have to switch over has cost around £2,500 a month from September to December. This will, of course, continue as and when our students return. It’s not a massive cost, but we now have to post out exercise books and workbooks, all of which adds up.

“On top of this, we’ve had the cost of plastic screens, covid-19 flow testing, additional PPE and additional cleaning. Our external caterers are now talking about invoicing us about £2,000 a week for the free school meal costs they would be taking, which means we will be paying for free school meals twice until the government refunds us for the voucher scheme.

“Our cash flow is under enough strain as it is without that, and we don’t have a surplus to fall on.”

*name has been anonymised.