The hidden

cost of

leading our

schools

The hidden cost of leading our schools

The case for nationally funded mental health support

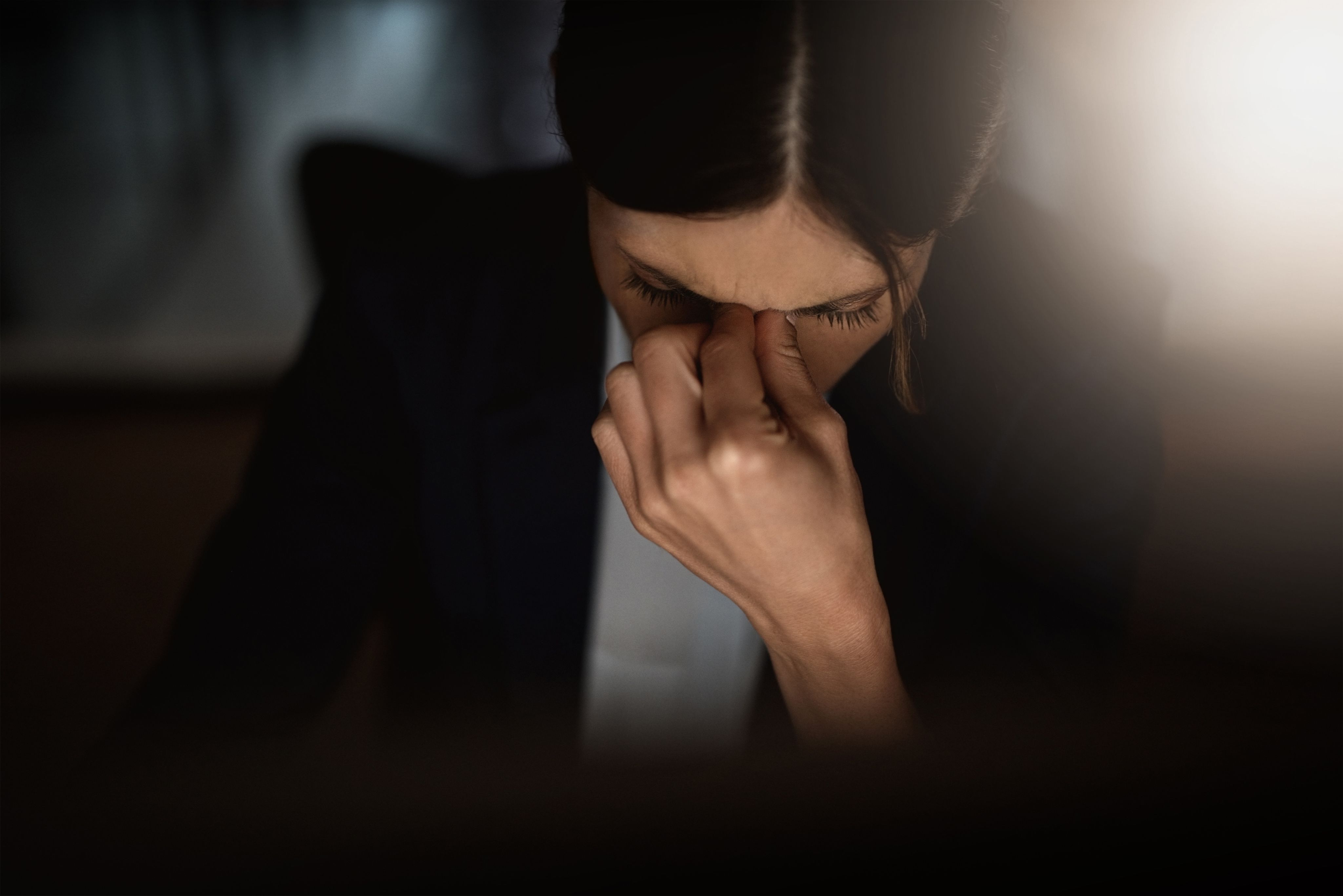

Back in the spring, NAHT research revealed that, shockingly, nearly two-thirds (65%) of school leaders felt their mental health had been harmed during the previous 12 months, with many simply quitting the profession as a result.

The poll of 1,500 senior school leaders also found nearly half (45%) had admitted to needing mental health support in the previous 12 months. Yet only a third (33%) had actually received any, with 5% saying it was unavailable at their school or trust and 7% not even knowing how to access help.

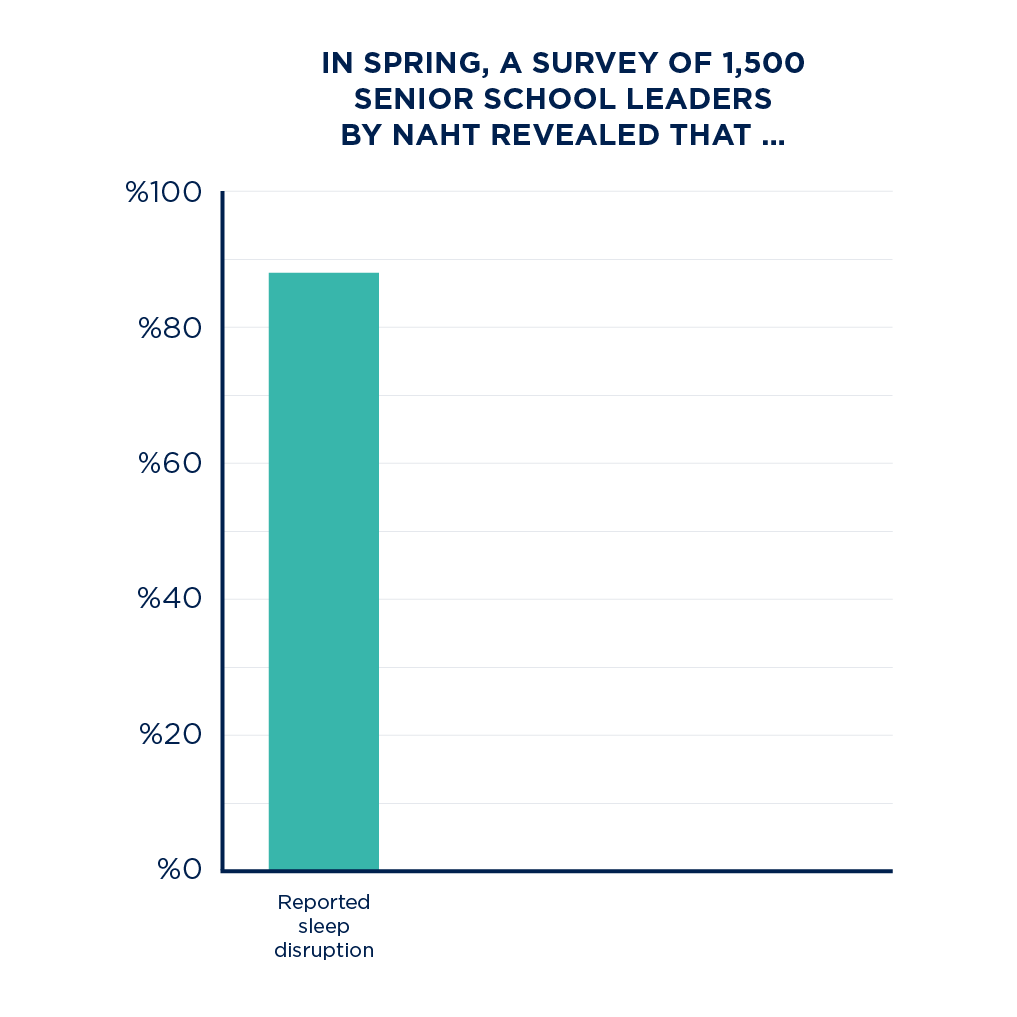

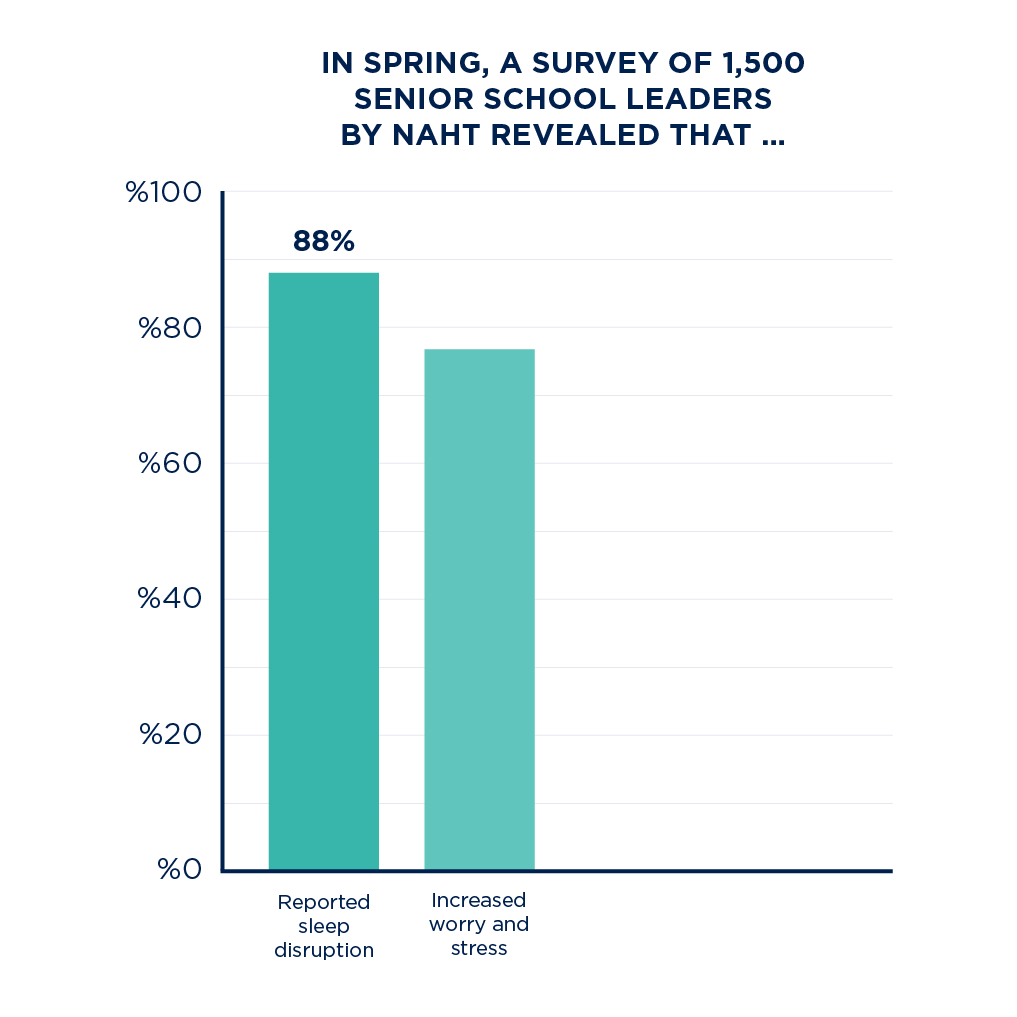

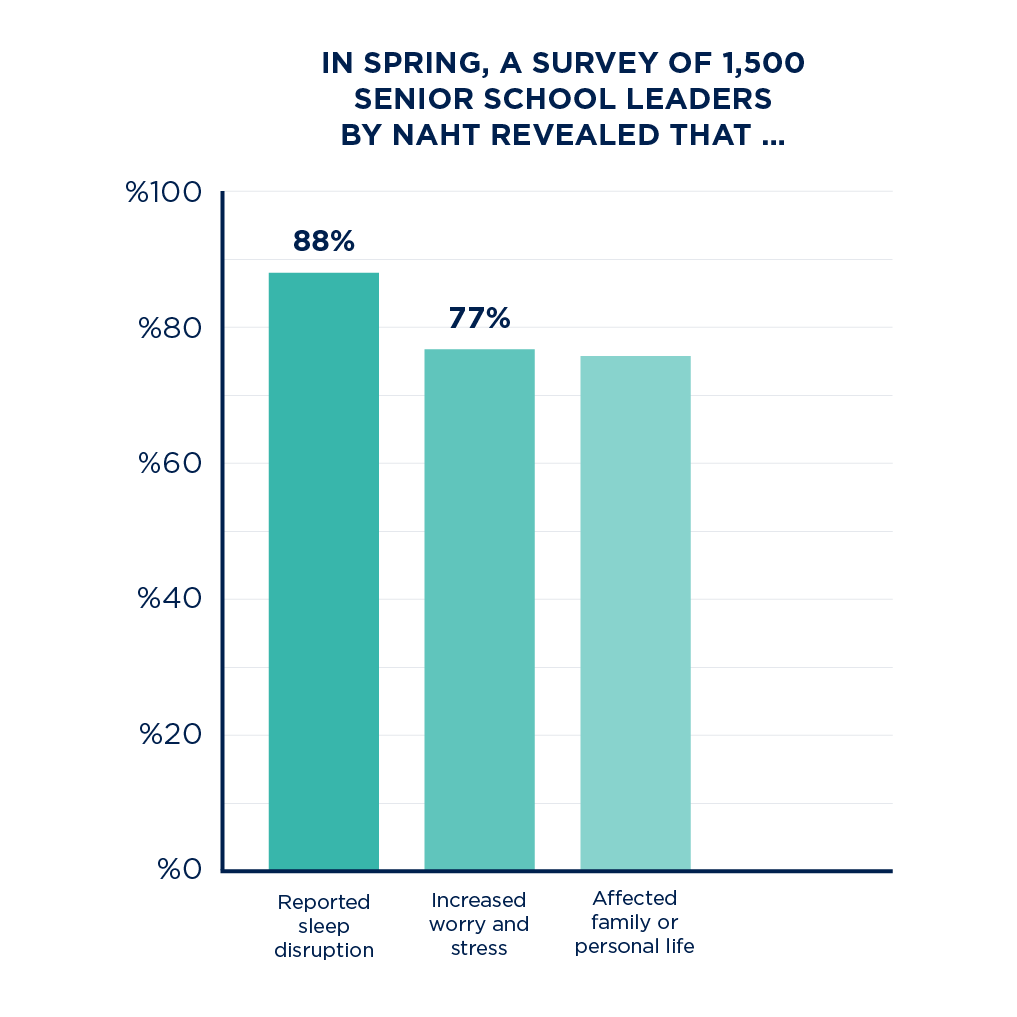

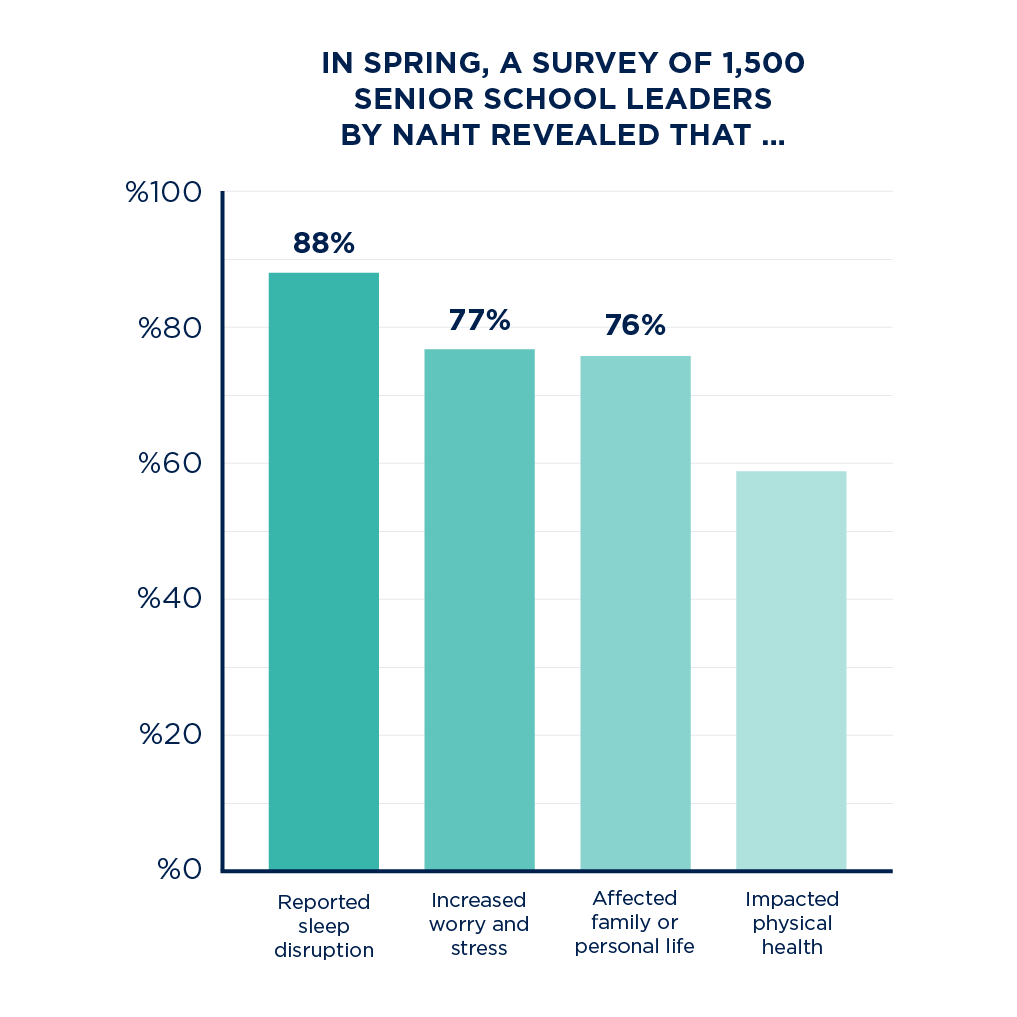

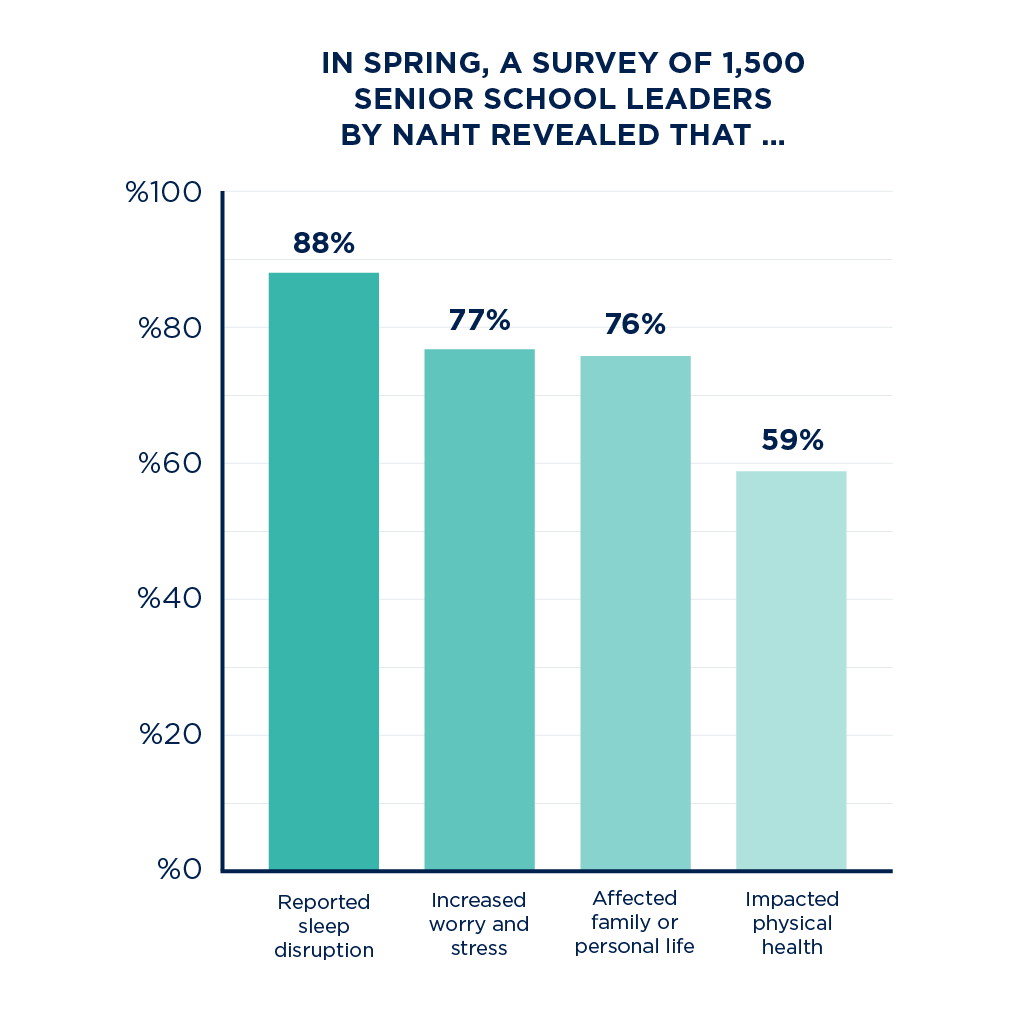

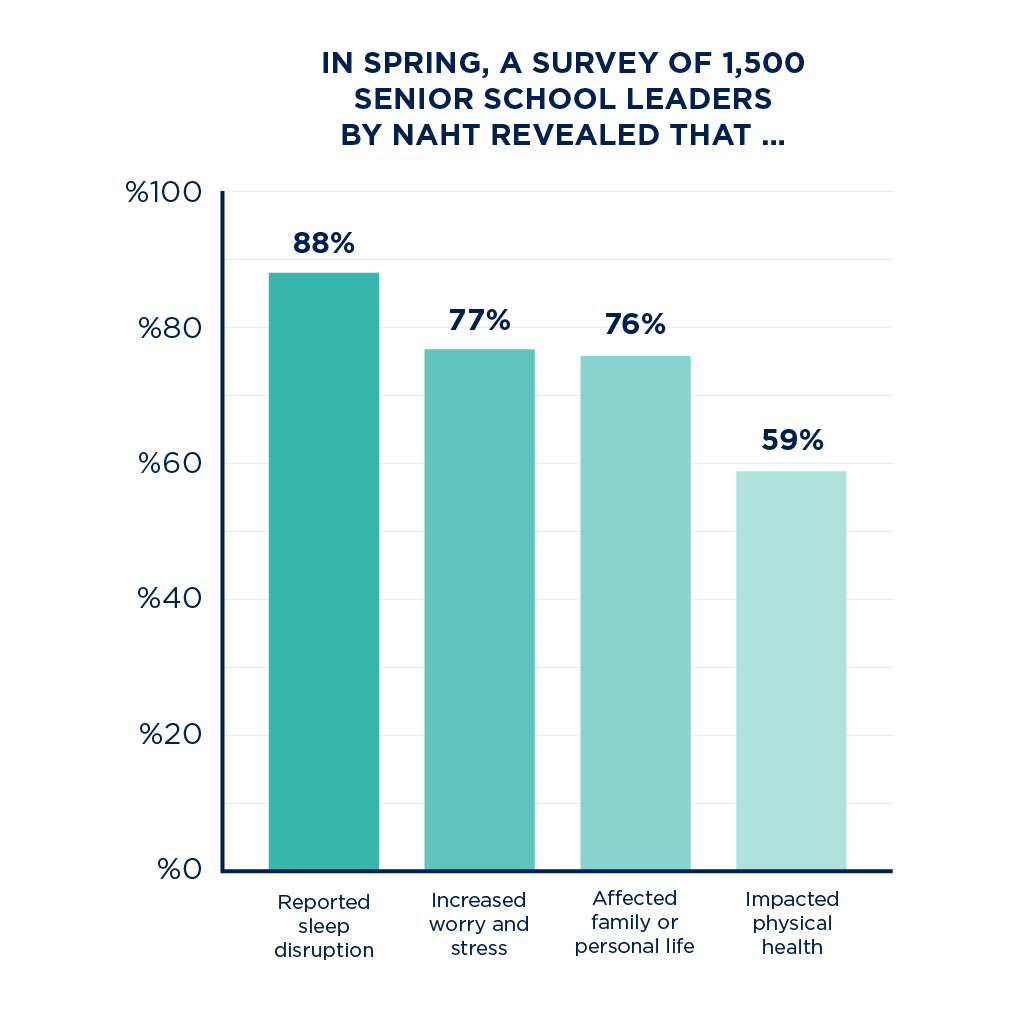

Nearly nine in 10 (88%) reported their role had affected their sleep, with 77% reporting increased worry and stress. More than three-quarters (76%) said it had negatively affected their family or personal life, and 59% said it negatively impacted their physical health.

This isn’t the first time NAHT has highlighted the heavy health toll that can come with being a modern-day school leader. In fact, if anything, the union’s ‘Crisis Point’ survey at the end of 2023 – with its broadly similar finding that 49% had needed mental and well-being support in the previous year, yet only 38% had been able to access it – suggests little has changed or improved in the past 18 months.

JAMES HAWKINS,

NAHT BRANCH PRESIDENT, BIRMINGHAM

This also illustrates why mental health and well-being support was such a talking point at May’s NAHT Annual Conference, with a motion from James Hawkins, NAHT’s Birmingham branch president and a member of NAHT’s Deputy and Assistant Heads’ Sector Council, calling for more funded well-being support – something currently available for only some roles, restricted to six one-hour online sessions and open to just 840 people each year – to be made available for all school leaders.

“We need an urgent focus on supporting the mental health and well-being of school leaders through professional supervision. Conference calls on the national executive to urge the new government, as part of its mission to improve retention, to fully fund an ongoing entitlement to professional supervision for school leaders.”

The case for nationally funded mental health support

Back in the spring, NAHT research revealed that, shockingly, nearly two-thirds (65%) of school leaders felt their mental health had been harmed during the previous 12 months, with many simply quitting the profession as a result.

The poll of 1,500 senior school leaders also found nearly half (45%) had admitted to needing mental health support in the previous 12 months. Yet only a third (33%) had actually received any, with 5% saying it was unavailable at their school or trust and 7% not even knowing how to access help.

Nearly nine in 10 (88%) reported their role had affected their sleep, with 77% reporting increased worry and stress. More than three-quarters (76%) said it had negatively affected their family or personal life, and 59% said it negatively impacted their physical health.

This isn’t the first time NAHT has highlighted the heavy health toll that can come with being a modern-day school leader. In fact, if anything, the union’s ‘Crisis Point’ survey at the end of 2023 – with its broadly similar finding that 49% had needed mental and well-being support in the previous year, yet only 38% had been able to access it – suggests little has changed or improved in the past 18 months.

JAMES HAWKINS,

NAHT BRANCH PRESIDENT, BIRMINGHAM

This also illustrates why mental health and well-being support was such a talking point at May’s NAHT Annual Conference, with a motion from James Hawkins, NAHT’s Birmingham branch president and a member of NAHT’s Deputy and Assistant Heads’ Sector Council, calling for more funded well-being support – something currently available for only some roles, restricted to six one-hour online sessions and open to just 840 people each year – to be made available for all school leaders.

“We need an urgent focus on supporting the mental health and well-being of school leaders through professional supervision. Conference calls on the national executive to urge the new government, as part of its mission to improve retention, to fully fund an ongoing entitlement to professional supervision for school leaders.”

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

“It is very well understood that the job of being a school leader can be incredibly emotionally demanding at times. It can create all sorts of challenges; you can find yourself dealing with all sorts of difficult situations, which can have an impact on your well-being,” agrees NAHT assistant general secretary James Bowen.

“We have seen some progress in recent years. As James Hawkins’s motion shows, the government has started funding programmes through charities like Education Support. But for us, it doesn’t go far enough.

“But it shouldn’t be something that only happens on a case-by-case basis. We’d like to see the government fully fund mental health support for all school leaders across the country. It is as simple as that,” James tells Leadership Focus.

Tailored mental health and coaching support for school leaders

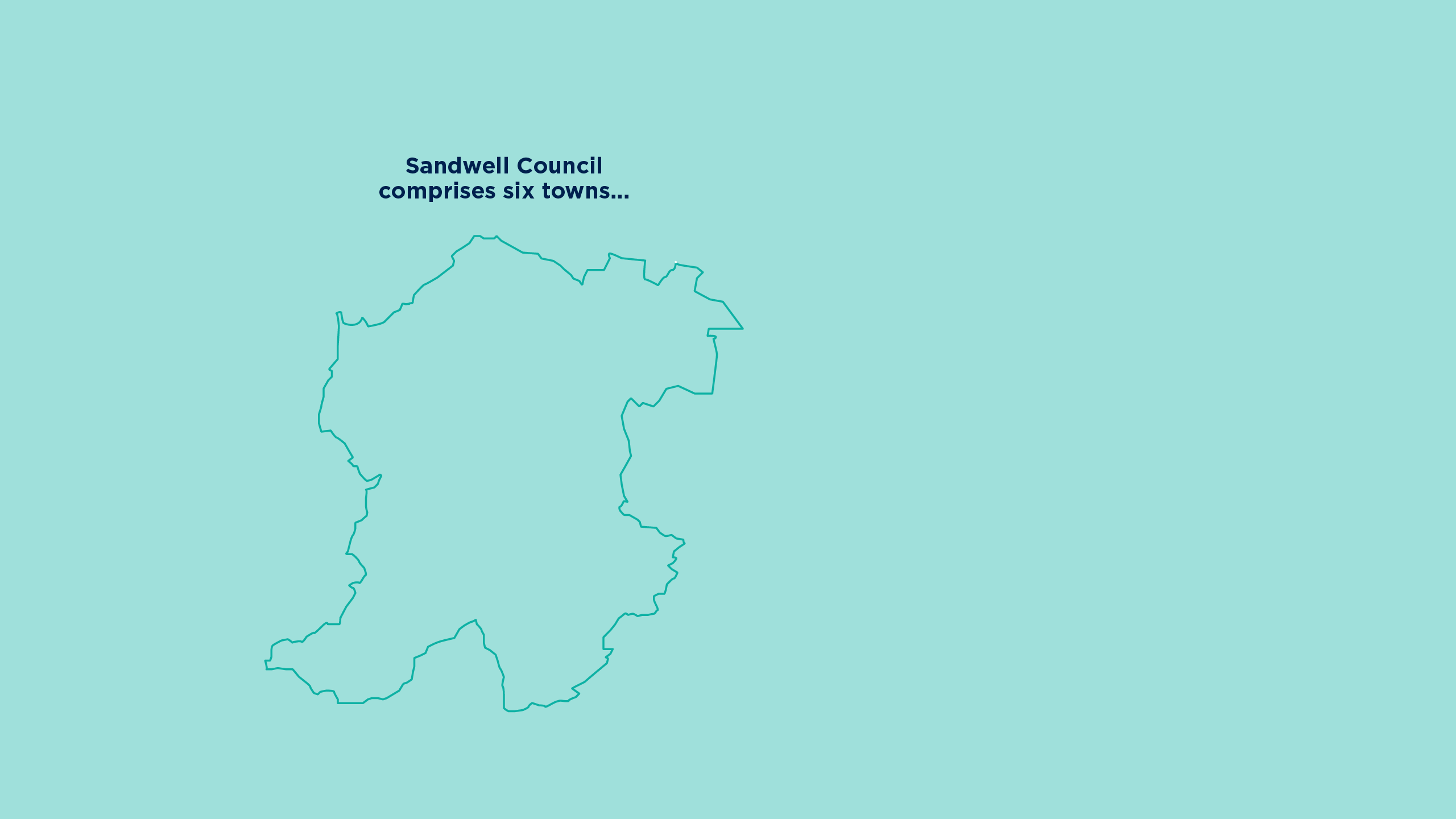

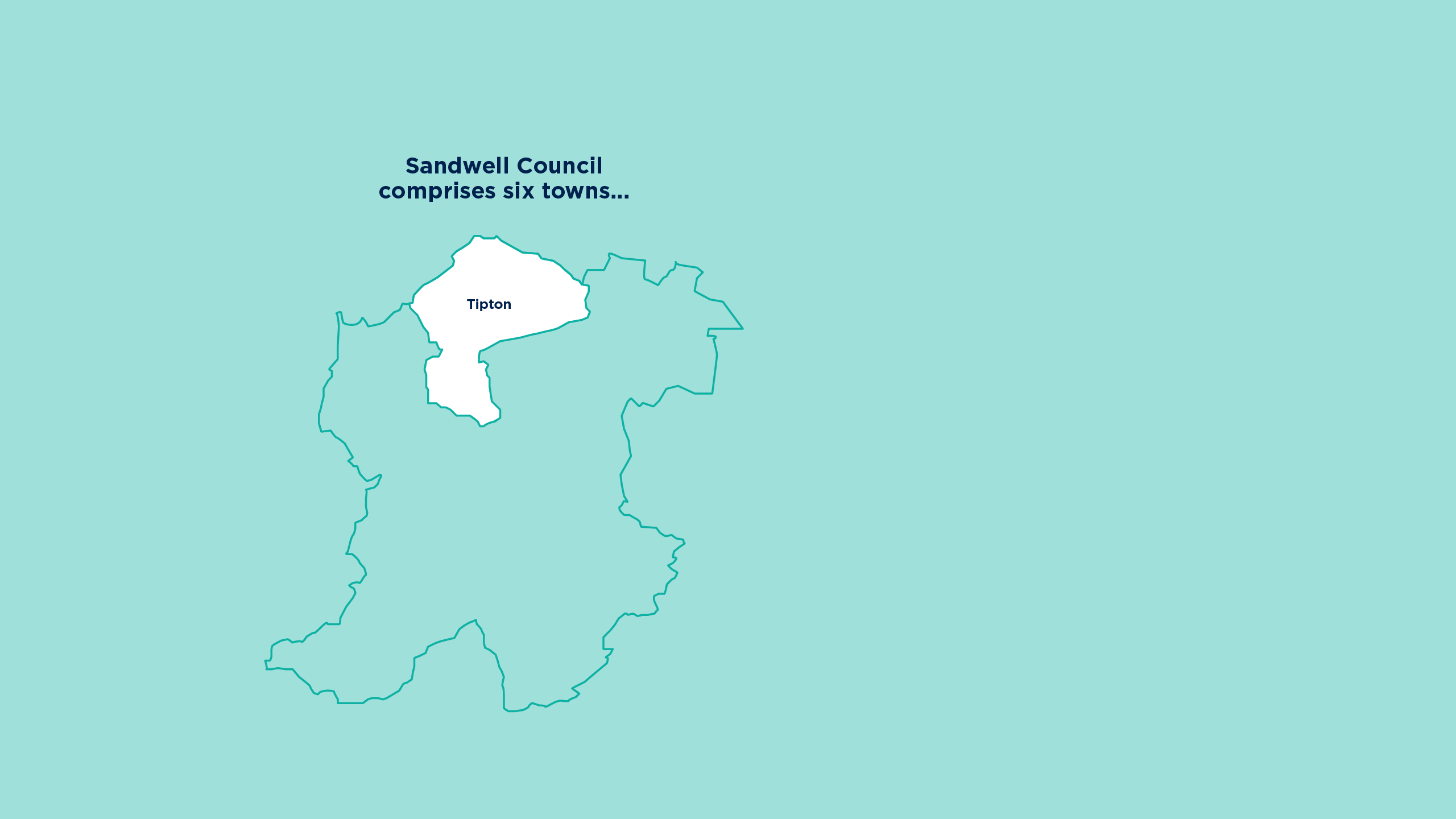

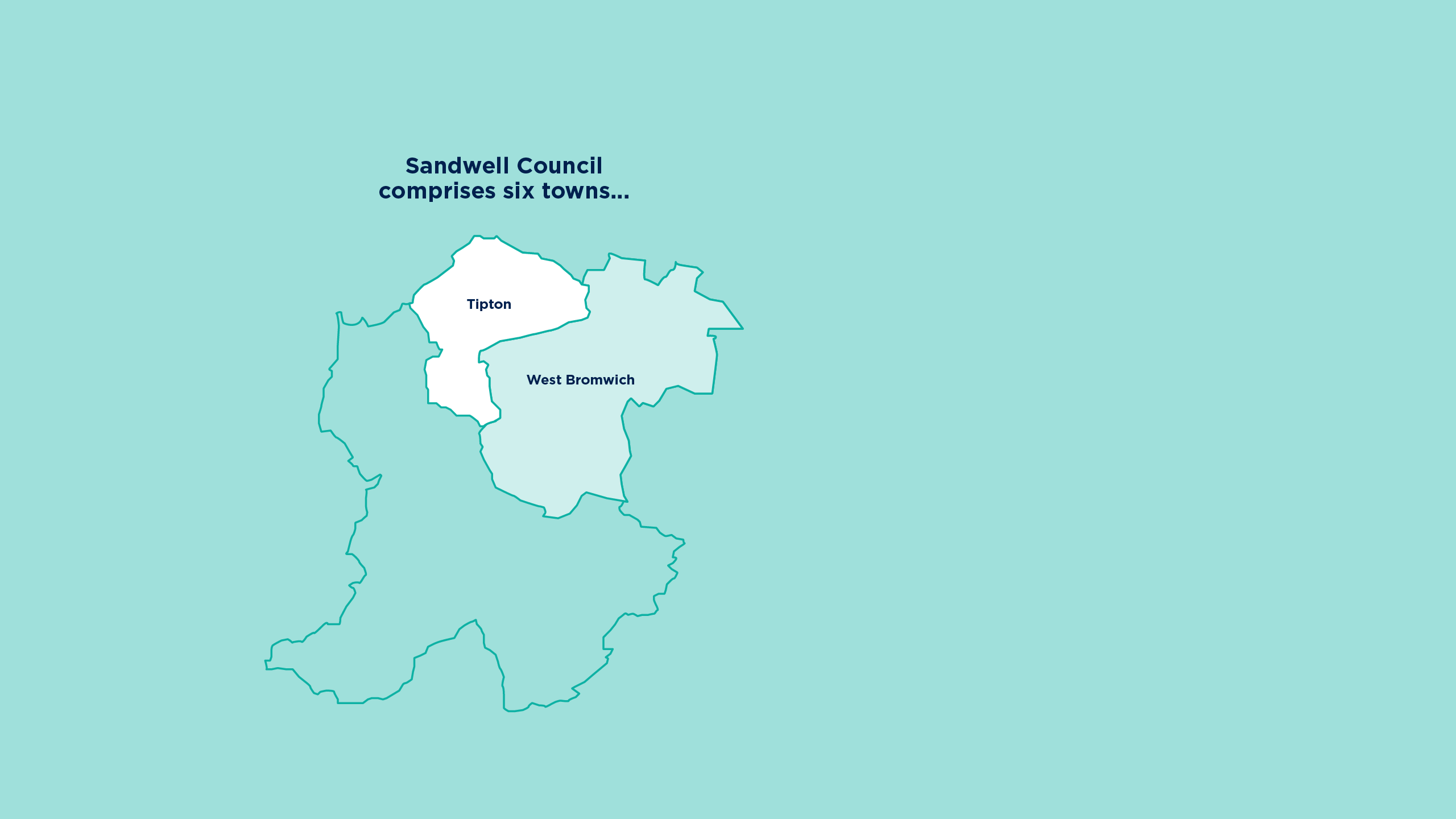

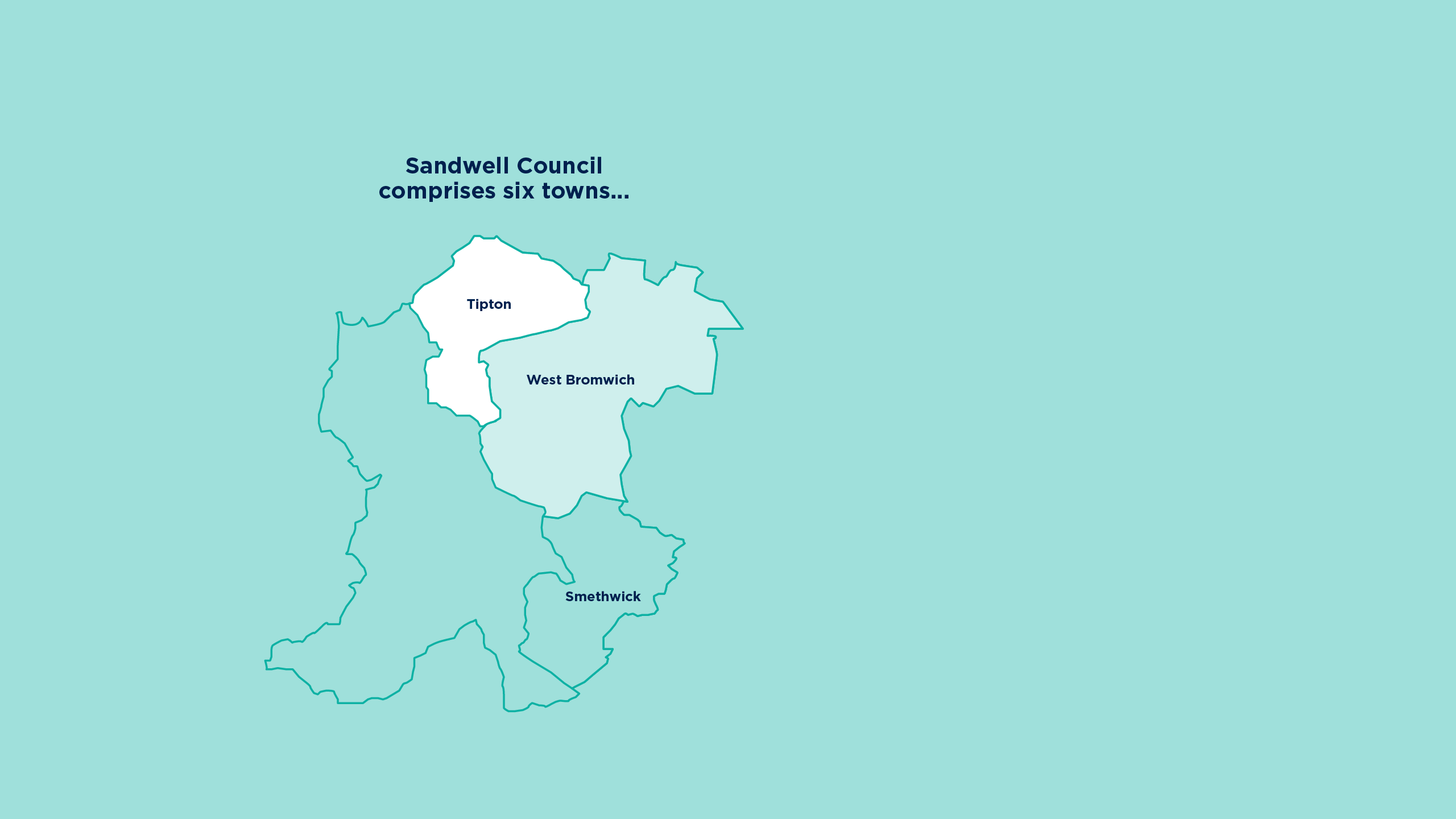

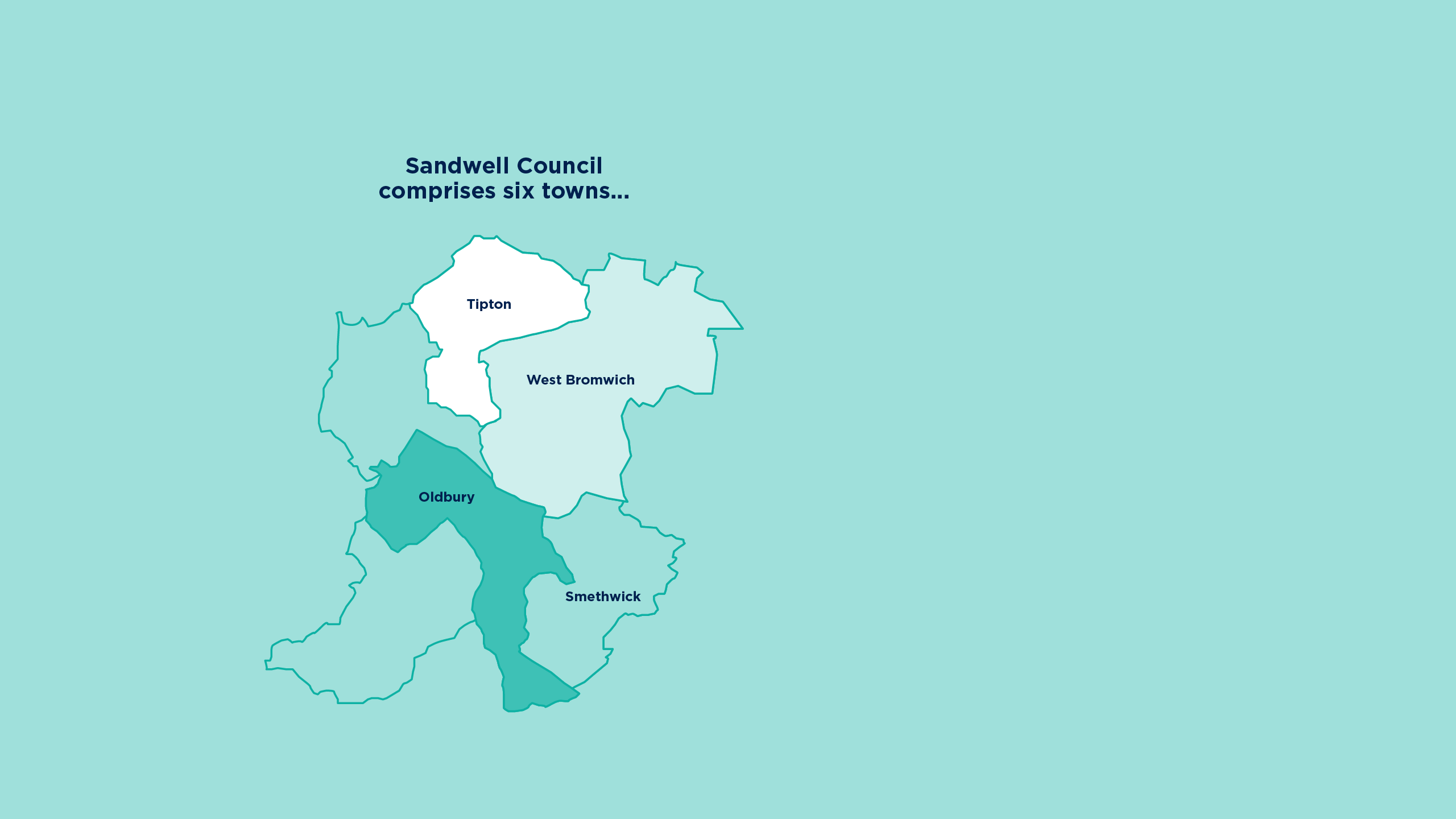

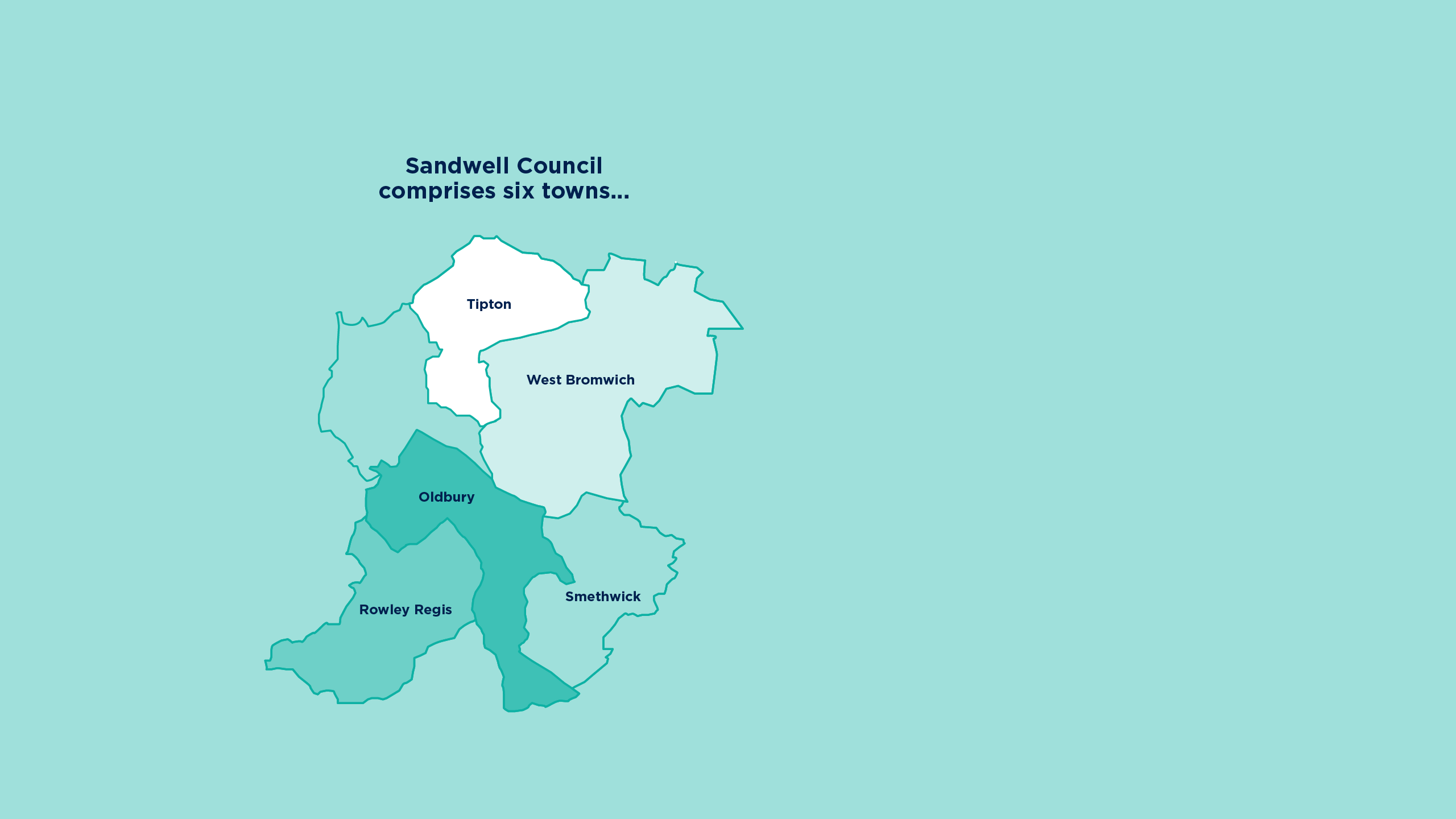

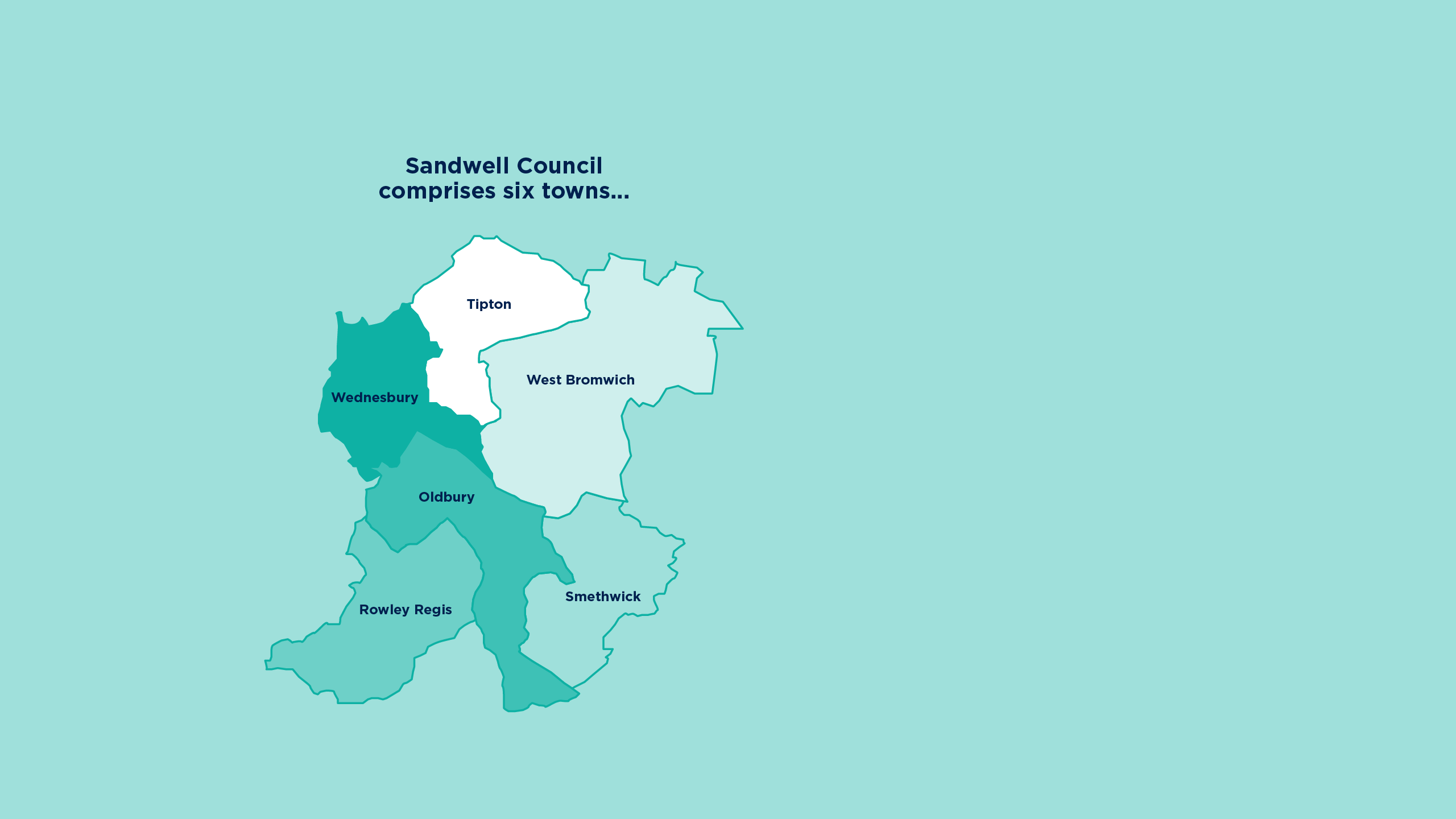

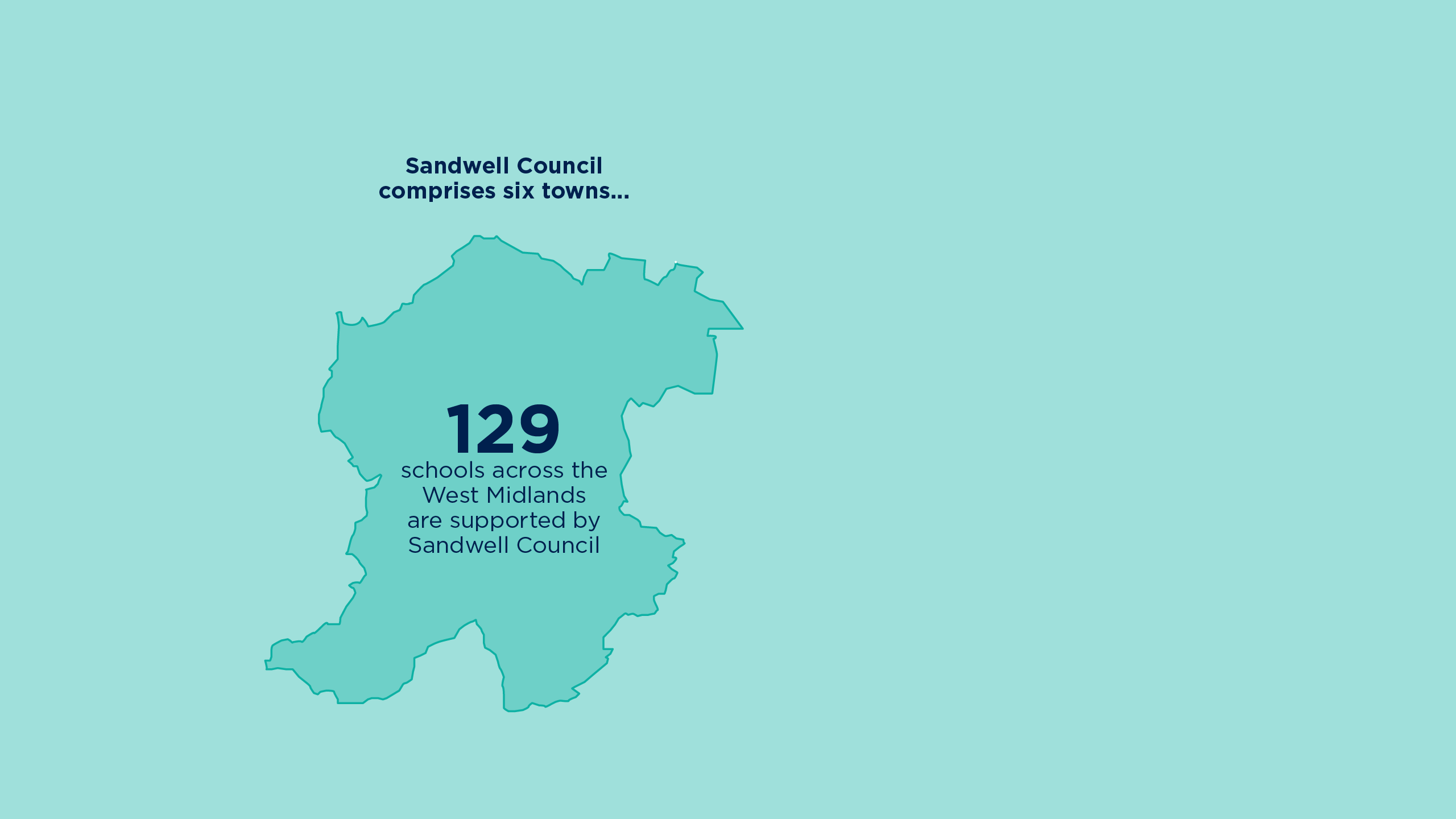

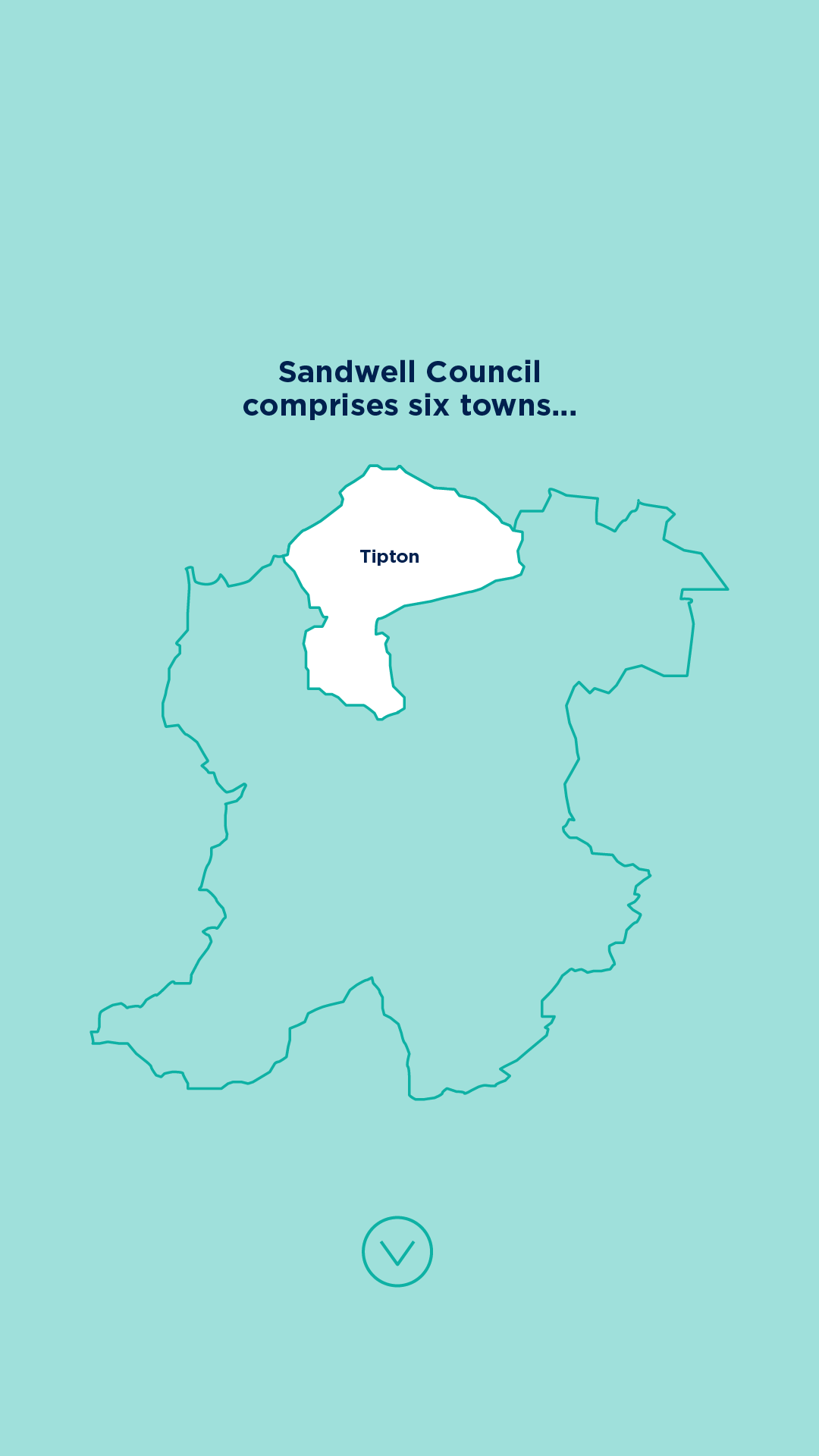

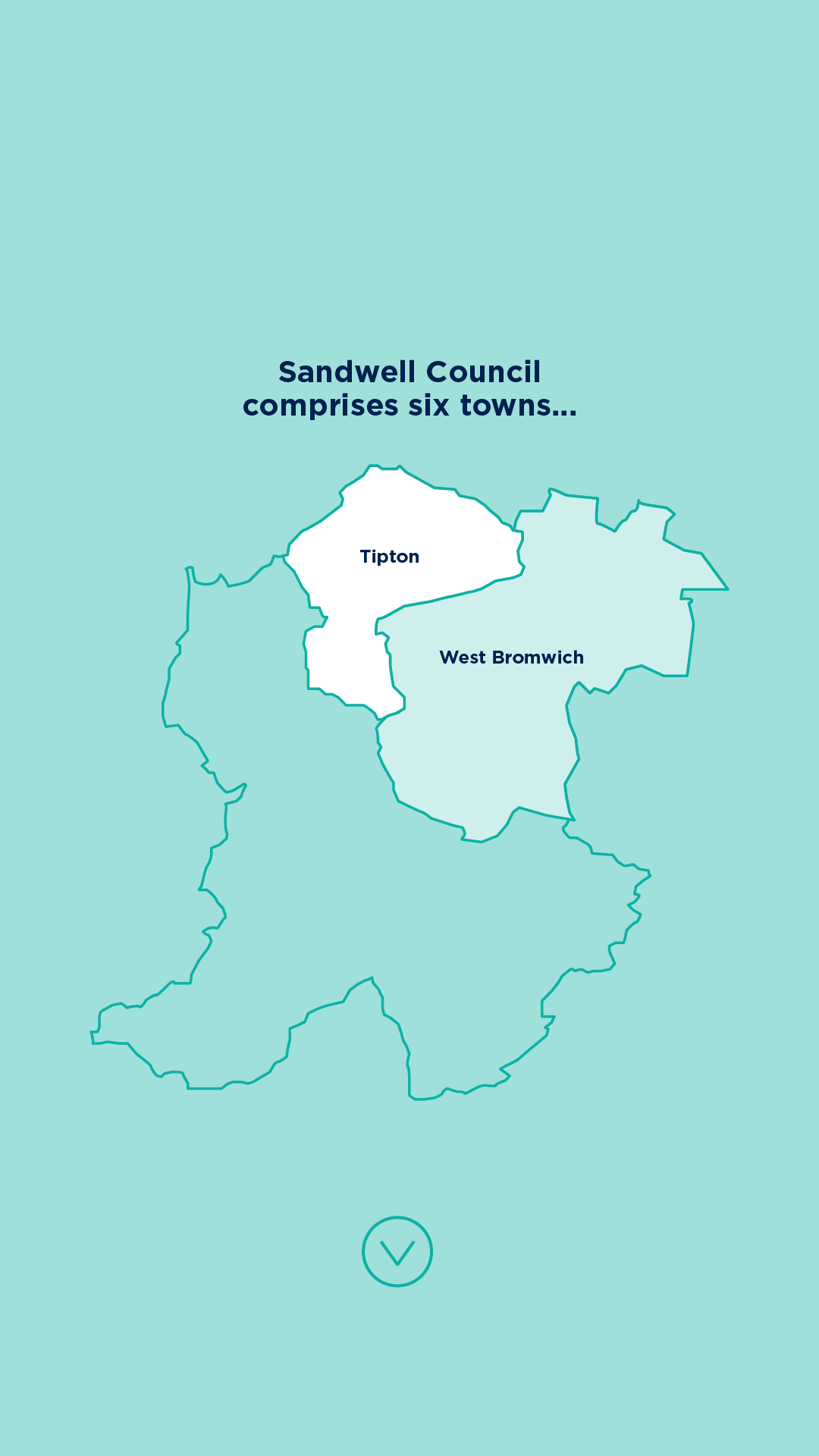

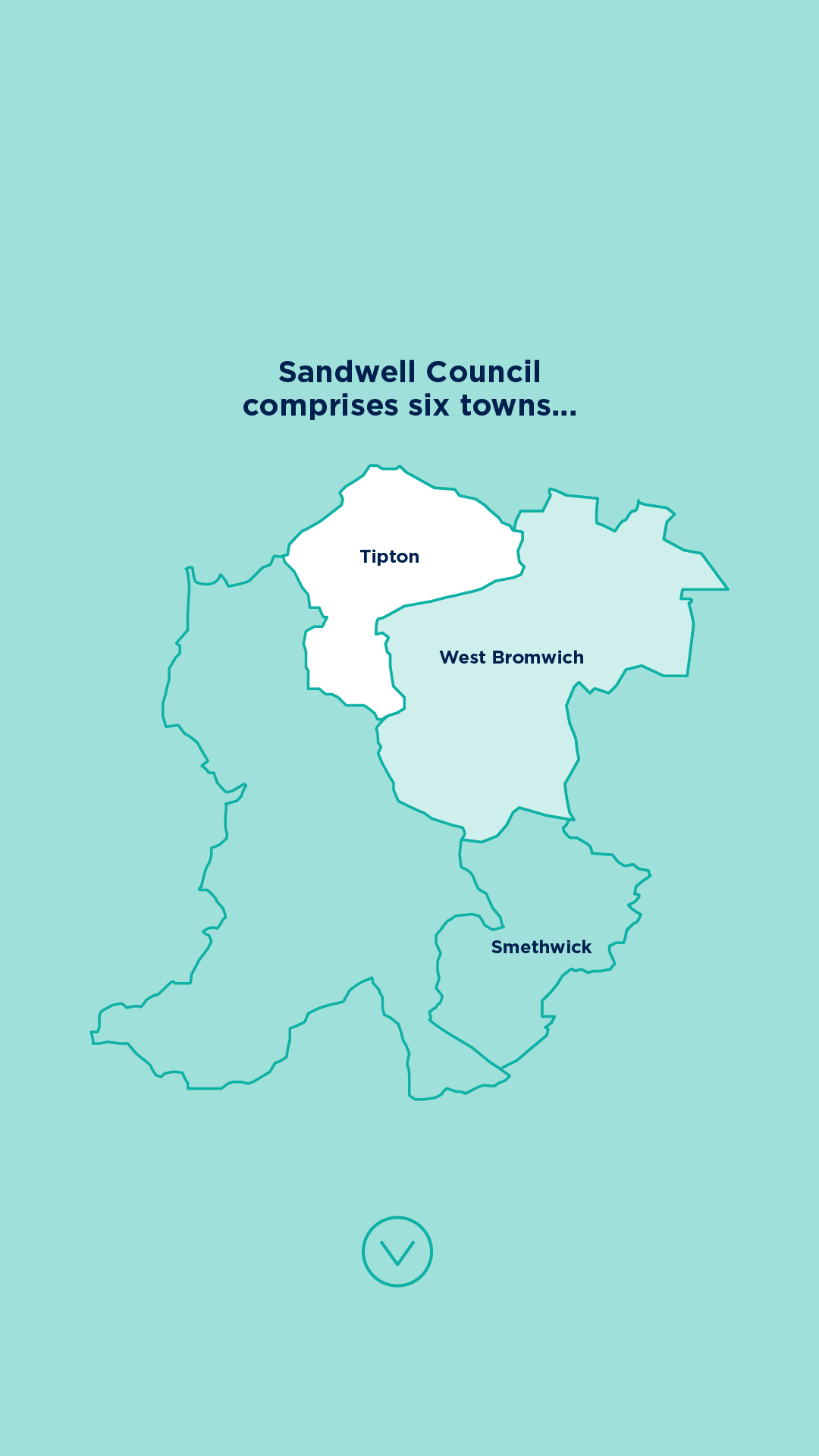

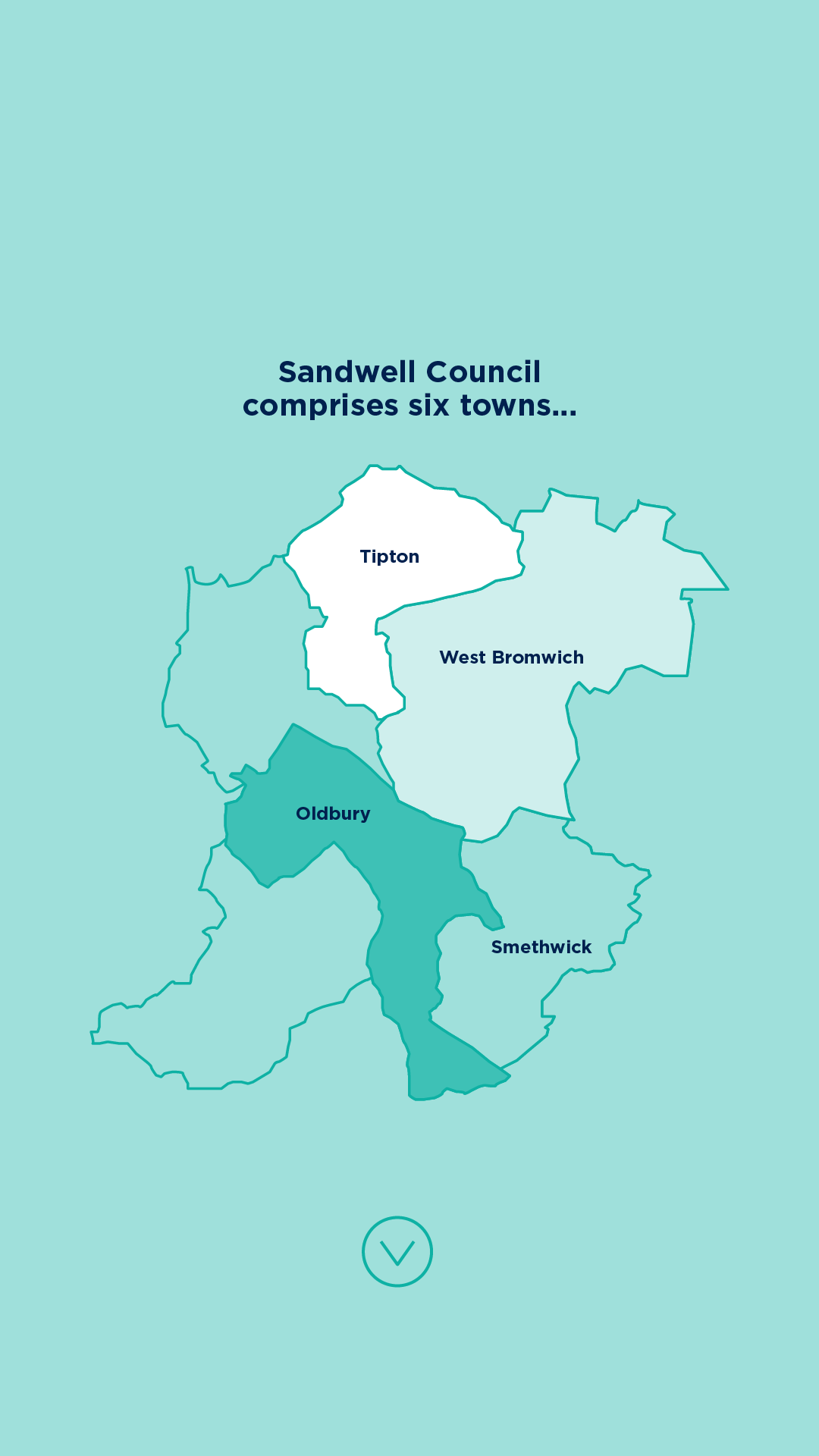

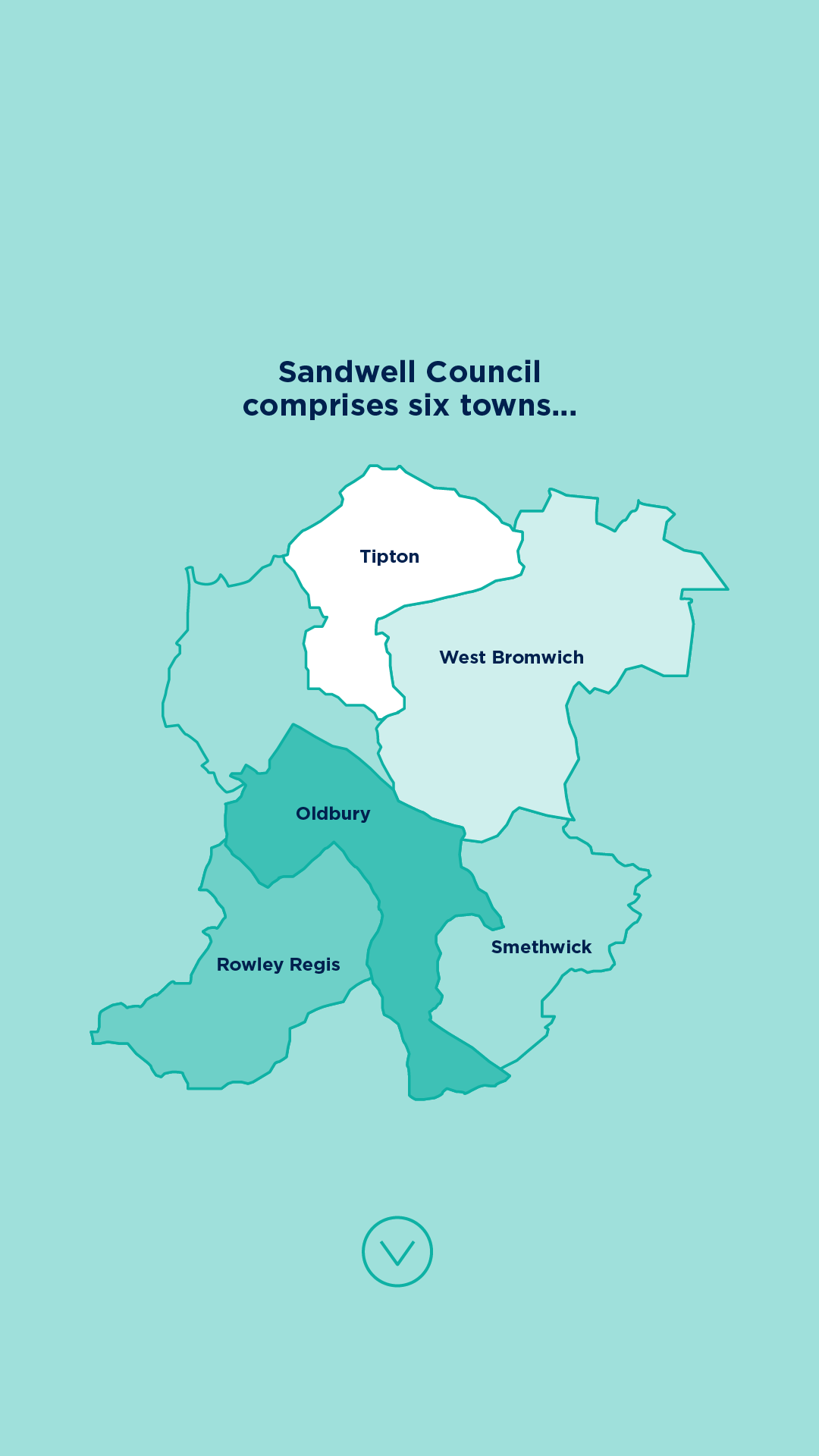

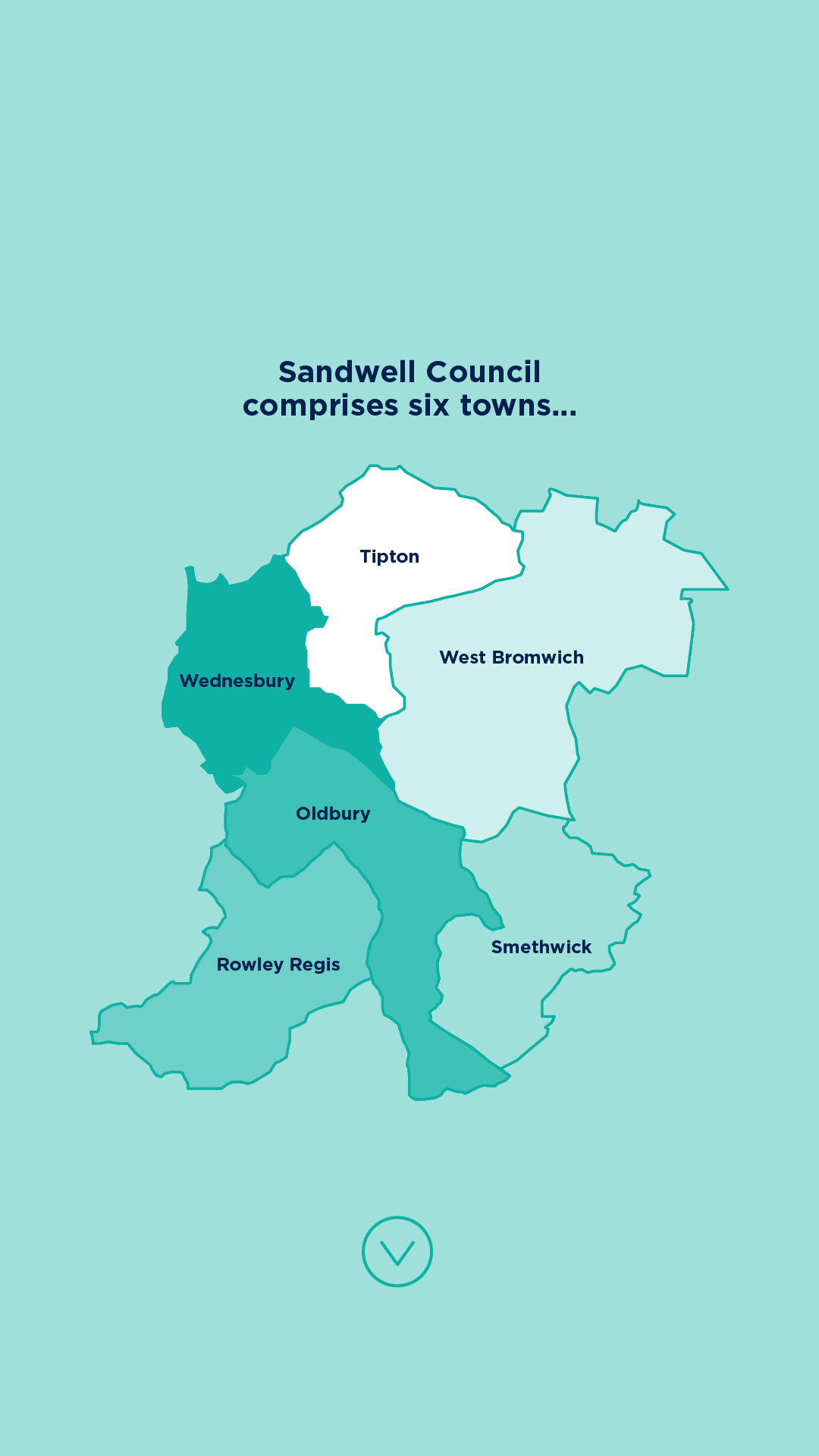

A recent initiative by Sandwell Council for its 129 schools across the West Midlands has illustrated very clearly what can be achieved, even if still only at a local level. However, arguably, it also illustrates what could be achieved nationally if the government was prepared to put serious money behind national provisions.

Working with provider HeadsUp4HTs and in a scheme funded by the Sandwell Council’s public health department and delivered in collaboration with colleagues in its children and education department, school leaders across the borough have been able to access a combination of one-to-one counselling, one-to-one coaching support and group peer support.

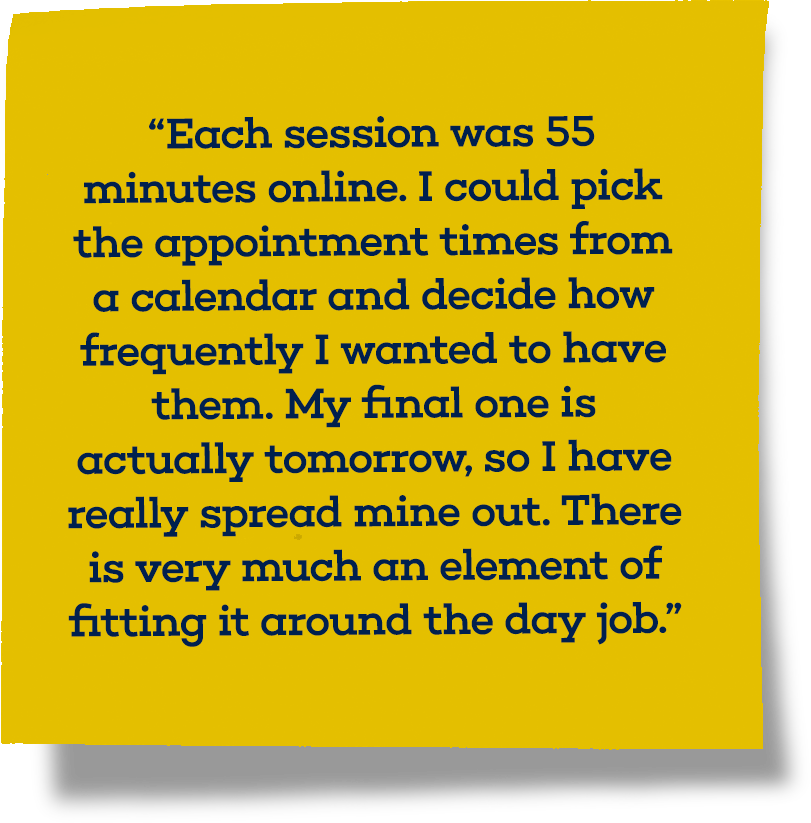

Under the initiative, school leaders have been able to choose from three pathways: either six online one-to-one counselling sessions, six online one-to-one coaching sessions, or two one-to-one coaching sessions that bookend four peer-coaching sessions. These latter sessions, also online, normally bring together some 15 school leaders from across the borough to discuss and reflect on shared issues or problems.

Since last autumn, some 109 school leaders – head teachers, deputy head teachers and assistant head teachers – have gone through the programme, with 40 having chosen one-to-one coaching, 22 the counselling and 47 the coaching with peer sessions.

JACKIE BEECH,

HEAD TEACHER AT ALL SAINTS CHURCH OF ENGLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL, WEST BROMWICH

“I did the one-to-one coaching model,” explains Jackie Beech, head teacher at All Saints Church of England Primary School in West Bromwich.

The exact nature of this coaching conversation will, of course, vary from person to person and school to school. You can focus on anything from operational or professional issues to simply talking something through to gain more of a mental handle on it.

“It is not just about pouring out how you feel,” Jackie emphasises, although it can become that, if you wish. “It is about being very purposeful and intentional – about trying to map out your day. For example, if I notice a week where my head feels overcrowded, hectic or panicked, I can ask myself, ‘Well, why was that? Why, for instance, did I choose to have all those parent meetings on the same morning? Why did I put myself in that headspace about that particular issue?’”

Tailored mental health and coaching support for school leaders

A recent initiative by Sandwell Council for its 129 schools across the West Midlands has illustrated very clearly what can be achieved, even if still only at a local level. However, arguably, it also illustrates what could be achieved nationally if the government was prepared to put serious money behind national provisions.

Working with provider HeadsUp4HTs and in a scheme funded by the Sandwell Council’s public health department and delivered in collaboration with colleagues in its children and education department, school leaders across the borough have been able to access a combination of one-to-one counselling, one-to-one coaching support and group peer support.

Under the initiative, school leaders have been able to choose from three pathways: either six online one-to-one counselling sessions, six online one-to-one coaching sessions, or two one-to-one coaching sessions that bookend four peer-coaching sessions. These latter sessions, also online, normally bring together some 15 school leaders from across the borough to discuss and reflect on shared issues or problems.

Since last autumn, some 109 school leaders – head teachers, deputy head teachers and assistant head teachers – have gone through the programme, with 40 having chosen one-to-one coaching, 22 the counselling and 47 the coaching with peer sessions.

JACKIE BEECH,

HEAD TEACHER AT ALL SAINTS CHURCH OF ENGLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL, WEST BROMWICH

“I did the one-to-one coaching model,” explains Jackie Beech, head teacher at All Saints Church of England Primary School in West Bromwich.

The exact nature of this coaching conversation will, of course, vary from person to person and school to school. You can focus on anything from operational or professional issues to simply talking something through to gain more of a mental handle on it.

“It is not just about pouring out how you feel,” Jackie emphasises, although it can become that, if you wish. “It is about being very purposeful and intentional – about trying to map out your day. For example, if I notice a week where my head feels overcrowded, hectic or panicked, I can ask myself, ‘Well, why was that? Why, for instance, did I choose to have all those parent meetings on the same morning? Why did I put myself in that headspace about that particular issue?’”

Building a collaborative, borough-wide support network

The impetus for putting this support in place came from the recognition – as James Bowen’s comments above also illustrate – that being a school leader can often be, and indeed is, immensely emotionally and mentally challenging.

JULIE ANDREWS,

SANDWELL COUNCIL

As Julie Andrews, assistant director at Sandwell Council, puts it: “Being a head teacher, as we all know, is a highly pressured job; being a head teacher can often feel lonely because there can be many things that they have nobody to talk to about.

“It [this initiative] came from that space, really. We felt that if we were to do anything, it needed to be across the borough, in its entirety – not just offered to a few head teachers and school leaders, but all or nothing.

“The next step was to set up a head teacher working party. This was a representative group from our seven learning communities across Sandwell, ensuring everyone was represented. We started with a conversation about the pressures people face and what they felt would be useful to them.

“We were clear: if it was going to be meaningful moving forward, we needed to be led by head teachers; it had to be for them. So, the project was collaborative from start to finish,” Julie adds.

CLAIRE TATE,

SANDWELL COUNCIL

A further element of the planning process involved identifying what support was already available in the community, what free resources existed, and what support the council could already provide without the need to access extra provision, explains Claire Tate, Sandwell Council interim commissioning manager for statutory services for children.

“There was a slight backwards and forwards just to get it right. We needed to understand what was needed. For example, clinical supervision, coaching and counselling can all mean very different things to different people. Was it counselling people needed? Or peer support? Or coaching? What was already being accessed or working? We worked to break that down,” she adds.

Building a collaborative, borough-wide support network

The impetus for putting this support in place came from the recognition – as James Bowen’s comments above also illustrate – that being a school leader can often be, and indeed is, immensely emotionally and mentally challenging.

JULIE ANDREWS,

SANDWELL COUNCIL

As Julie Andrews, assistant director at Sandwell Council, puts it: “Being a head teacher, as we all know, is a highly pressured job; being a head teacher can often feel lonely because there can be many things that they have nobody to talk to about.

“It [this initiative] came from that space, really. We felt that if we were to do anything, it needed to be across the borough, in its entirety – not just offered to a few head teachers and school leaders, but all or nothing.

“The next step was to set up a head teacher working party. This was a representative group from our seven learning communities across Sandwell, ensuring everyone was represented. We started with a conversation about the pressures people face and what they felt would be useful to them.

“We were clear: if it was going to be meaningful moving forward, we needed to be led by head teachers; it had to be for them. So, the project was collaborative from start to finish,” Julie adds.

CLAIRE TATE,

SANDWELL COUNCIL

A further element of the planning process involved identifying what support was already available in the community, what free resources existed, and what support the council could already provide without the need to access extra provision, explains Claire Tate, Sandwell Council interim commissioning manager for statutory services for children.

“There was a slight backwards and forwards just to get it right. We needed to understand what was needed. For example, clinical supervision, coaching and counselling can all mean very different things to different people. Was it counselling people needed? Or peer support? Or coaching? What was already being accessed or working? We worked to break that down,” she adds.

The pressures of leadership and the need for peer support

“Being a head teacher is a great job; it has always been great, and I love my job,” agrees Jackie Beech. “But it is a pressurised job, and as social norms have changed, so too have the expectations placed on those in this role.

“These days, we are very public-facing and accessible – to our staff, children, parents and families. When we compare the role to, say, a GP, they can have online consultations or phone calls, and people can and do wait. Sometimes, in a school, the demands can just become more and more. So, a head teacher has to manage both the expectations of others and their own workload.

“We were finding that more and more people were leaving the profession or leaving sooner than they anticipated. I am an experienced head teacher, but I found – and I still find – that new head teachers to the profession often hit the ground running very quickly, and it can be quite overwhelming.

“There has been significant engagement with this initiative. It has been about creating a wellness space – a space where people have ‘permission’ to put themselves first. Because if we feel well as leaders, we can lead well. That, for me, is the key,” she adds.

CLAIRE EVANS,

HEAD TEACHER AT EATON VALLEY PRIMARY SCHOOL, WEST BROMWICH

“We all do the job because we love it,” agrees Claire Evans, head teacher at Eaton Valley Primary School in West Bromwich, NAHT Sandwell branch president and NAHT national executive member.

“We have lots of links with other learning communities, but you are still isolated as a head teacher. For example, I have a school that is less than a mile down the road from me, yet I don’t know what’s going on there. I might have an issue and be sitting there thinking, “Is it just me? Am I the only one facing this?” You can fall into the trap of thinking it’s a ‘you’ problem and a ‘you’ issue. The peer support groups have enabled us to talk to each other and go, ‘Oh, I felt like that last week, too’,” she adds.

KATE HICKMAN,

SANDWELL COUNCIL

“Most of those accessing counselling did so because they were experiencing more acute mental distress and well-being issues that needed resolving. The coaching, in turn, helped the head teachers to develop the skills they needed to improve their environment or whatever they chose to focus on,” explains Kate Hickman of Sandwell Council’s public health team and manager of the council’s vulnerable groups programme.

The pressures of leadership and the need for peer support

“Being a head teacher is a great job; it has always been great, and I love my job,” agrees Jackie Beech. “But it is a pressurised job, and as social norms have changed, so too have the expectations placed on those in this role.

“These days, we are very public-facing and accessible – to our staff, children, parents and families. When we compare the role to, say, a GP, they can have online consultations or phone calls, and people can and do wait. Sometimes, in a school, the demands can just become more and more. So, a head teacher has to manage both the expectations of others and their own workload.

“We were finding that more and more people were leaving the profession or leaving sooner than they anticipated. I am an experienced head teacher, but I found – and I still find – that new head teachers to the profession often hit the ground running very quickly, and it can be quite overwhelming.

“There has been significant engagement with this initiative. It has been about creating a wellness space – a space where people have ‘permission’ to put themselves first. Because if we feel well as leaders, we can lead well. That, for me, is the key,” she adds.

CLAIRE EVANS,

HEAD TEACHER AT EATON VALLEY PRIMARY SCHOOL, WEST BROMWICH

“We all do the job because we love it,” agrees Claire Evans, head teacher at Eaton Valley Primary School in West Bromwich, NAHT Sandwell branch president and NAHT national executive member.

“We have lots of links with other learning communities, but you are still isolated as a head teacher. For example, I have a school that is less than a mile down the road from me, yet I don’t know what’s going on there. I might have an issue and be sitting there thinking, “Is it just me? Am I the only one facing this?” You can fall into the trap of thinking it’s a ‘you’ problem and a ‘you’ issue. The peer support groups have enabled us to talk to each other and go, ‘Oh, I felt like that last week, too’,” she adds.

KATE HICKMAN,

SANDWELL COUNCIL

“Most of those accessing counselling did so because they were experiencing more acute mental distress and well-being issues that needed resolving. The coaching, in turn, helped the head teachers to develop the skills they needed to improve their environment or whatever they chose to focus on,” explains Kate Hickman of Sandwell Council’s public health team and manager of the council’s vulnerable groups programme.

Building a lasting legacy of support for school leaders

Importantly, too, even though the formal programme is now coming to an end, the peer support sessions, in particular, will be able to continue, facilitated by the head teachers themselves. “The idea is that the skills learnt in those peer sessions mean that head teachers can facilitate those moving forward. So, there is no reliance on needing that funding. There is that legacy in place, that legacy of support,” Kate adds.

In Claire Evans’s case, for example, the peer group now meets every first Thursday of the month. “They always start with a check-in; we go around the room and ask people to identify how they’re feeling, and you’re not allowed just to say ‘fine’!” she explains.

“Then we pose a question, for example: ‘What brings you joy?’ We’ll have time to be quiet and allow people to think about it, and then we will talk about that. It is a different question each week, which is up to the facilitator to choose,” she adds.

DR ANNA BLENNERHASSETT,

SANDWELL COUNCIL

“It has been part of a culture shift,” emphasises Dr Anna Blennerhassett, consultant in public health at Sandwell Council and co-chair of its children and young people’s emotional health and well-being work stream.

“For us in public health, it has been part of taking a whole-school approach to preventing mental ill health and promoting good health. It is not distinct from what we’re seeing with children and young people in Sandwell as well – their social, emotional and mental health needs have also risen over the last five to 10 years, in line with the national trends.

What’s more, given that the initiative only cost approximately £70,000 and, as we have seen, intends to embed a long-term health and well-being legacy and culture shift, it has already been, arguably, great value for money.

All of which leads us back to that wider conversation about whether or how the government could be encouraged to support a wider national rollout of or investment in this type of support.

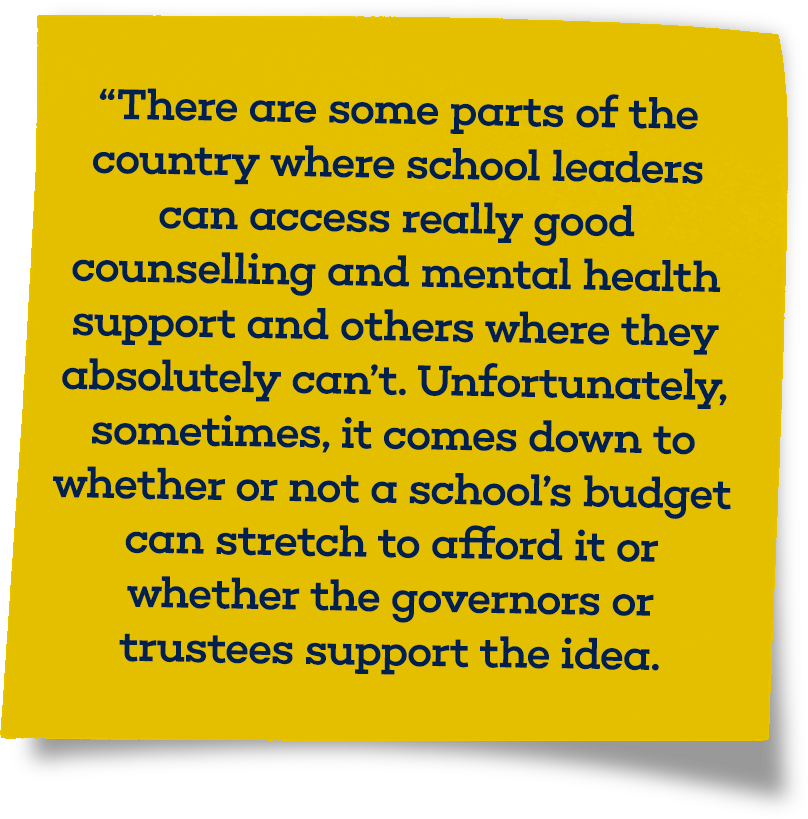

The challenge, as Claire Evans identifies, is that the success of local schemes such as the one in Sandwell may simply encourage the Department for Education (DfE) to throw the ball back into the local authority’s court – or, worse, leave it up to individual schools to fund.

“We don’t want the DfE to think all schools should fund this themselves. This is about investing in the workforce, which is what Sandwell has done. But it is what the DfE needs to do,” she emphasises.

“It should be an entitlement coming into the profession, part of the professional package of being a school leader,” agrees James Bowen. “We are very clear that all school leaders should be able to access this type of support. We know that it’s not only head teachers who experience the emotional demands of school leadership, hence why we want to see this sort of support made more widely available.

“Yes, we recognise there will be a cost to it. But you can argue that if it retains school leaders in the profession for longer and means they will be more effective at their job, then it will more than pay for itself,” he says, concluding with a thought that very much echoes the sentiments of All Saints’ Jackie Beech. “A healthy and well leader is more likely to be an effective leader.”

Building a lasting legacy of support for school leaders

Importantly, too, even though the formal programme is now coming to an end, the peer support sessions, in particular, will be able to continue, facilitated by the head teachers themselves. “The idea is that the skills learnt in those peer sessions mean that head teachers can facilitate those moving forward. So, there is no reliance on needing that funding. There is that legacy in place, that legacy of support,” Kate adds.

In Claire Evans’s case, for example, the peer group now meets every first Thursday of the month. “They always start with a check-in; we go around the room and ask people to identify how they’re feeling, and you’re not allowed just to say ‘fine’!” she explains.

“Then we pose a question, for example: ‘What brings you joy?’ We’ll have time to be quiet and allow people to think about it, and then we will talk about that. It is a different question each week, which is up to the facilitator to choose,” she adds.

DR ANNA BLENNERHASSETT,

SANDWELL COUNCIL

“It has been part of a culture shift,” emphasises Dr Anna Blennerhassett, consultant in public health at Sandwell Council and co-chair of its children and young people’s emotional health and well-being work stream.

“For us in public health, it has been part of taking a whole-school approach to preventing mental ill health and promoting good health. It is not distinct from what we’re seeing with children and young people in Sandwell as well – their social, emotional and mental health needs have also risen over the last five to 10 years, in line with the national trends.

What’s more, given that the initiative only cost approximately £70,000 and, as we have seen, intends to embed a long-term health and well-being legacy and culture shift, it has already been, arguably, great value for money.

All of which leads us back to that wider conversation about whether or how the government could be encouraged to support a wider national rollout of or investment in this type of support.

The challenge, as Claire Evans identifies, is that the success of local schemes such as the one in Sandwell may simply encourage the Department for Education (DfE) to throw the ball back into the local authority’s court – or, worse, leave it up to individual schools to fund.

“We don’t want the DfE to think all schools should fund this themselves. This is about investing in the workforce, which is what Sandwell has done. But it is what the DfE needs to do,” she emphasises.

“It should be an entitlement coming into the profession, part of the professional package of being a school leader,” agrees James Bowen. “We are very clear that all school leaders should be able to access this type of support. We know that it’s not only head teachers who experience the emotional demands of school leadership, hence why we want to see this sort of support made more widely available.

“Yes, we recognise there will be a cost to it. But you can argue that if it retains school leaders in the profession for longer and means they will be more effective at their job, then it will more than pay for itself,” he says, concluding with a thought that very much echoes the sentiments of All Saints’ Jackie Beech. “A healthy and well leader is more likely to be an effective leader.”