‘The words you use to a child become their inner voice.’

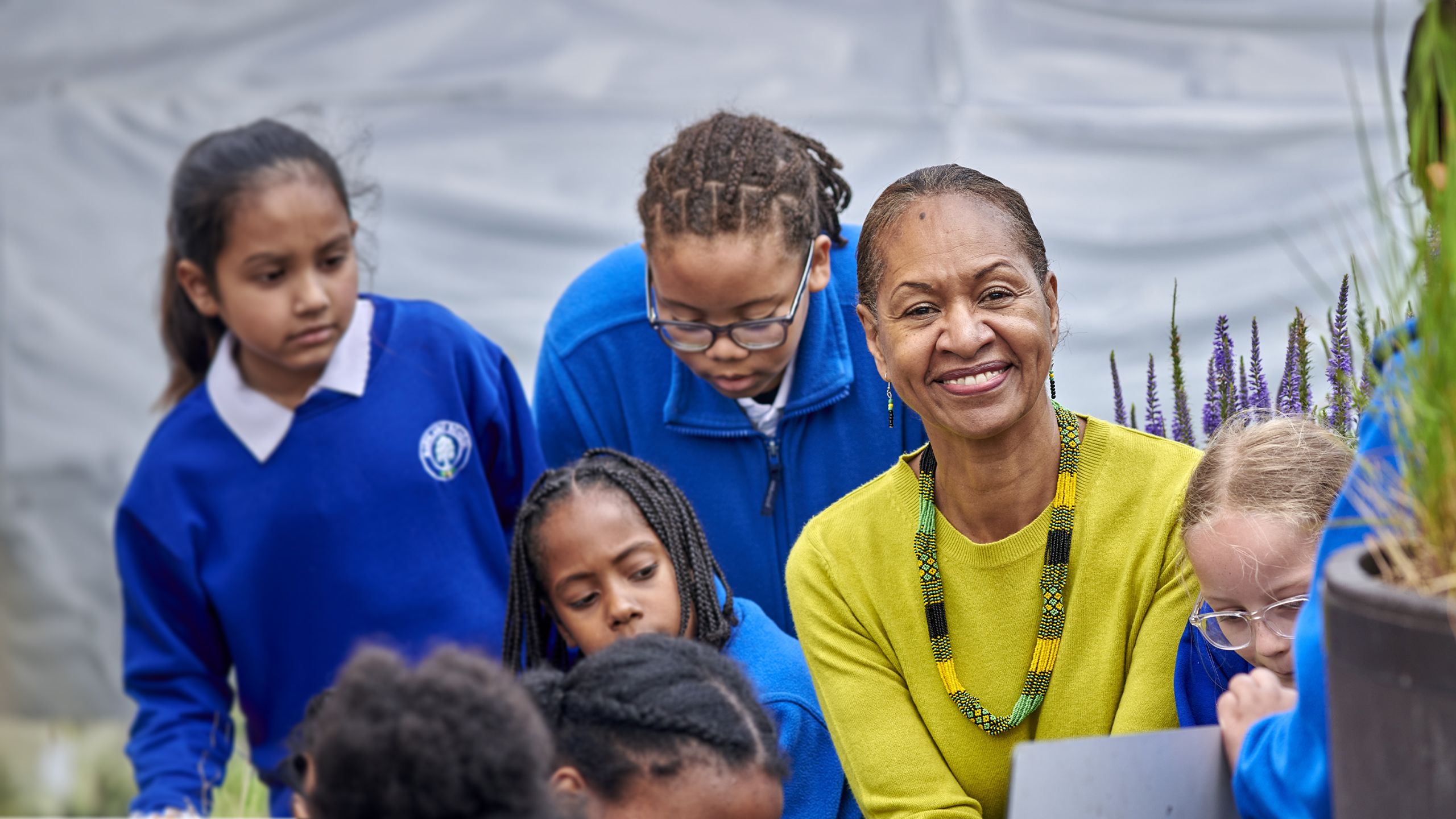

Journalist Nic Paton speaks to Lorna Jackson MBE, head teacher of Maryland Primary School in Stratford, about her pioneering work and approach to inclusion, equality and equity.

With more than 450 children representing 37 countries, 40 different languages and 44 dialects, it stands to reason that Maryland Primary School in Stratford, East London, will always be a diverse and multicultural hub for its community.

LORNA JACKSON MBE,

HEAD TEACHER, MARYLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL

The school, led by head teacher Lorna Jackson MBE, is much more than simply a cultural and community melting pot, however.

Lorna was recently awarded the freedom of the borough of Newham for her 45 years of teaching service; she is the longest-serving teacher and school leader in the authority. The school has been widely recognised and celebrated for its pioneering work and approach to inclusion, equality and equity.

In fact, Maryland supports and trains many school leaders, not just in the UK but around the world, working to instil its practical approach to embedding equality into the curriculum and ethos of the school.

ANASTASIA BOREHAM,

DEPUTY HEAD TEACHER, MARYLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL

Maryland’s deputy head teacher, Anastasia Boreham, points out, for example, that the school’s equality team recently carried out online training on embedding gender equality with four universities across China. Additionally, it hosts a large group of Japanese educators who visit Maryland annually. Research visits to Japan, Singapore, China, Bangladesh, Finland, Sweden and the Netherlands have shaped Maryland’s philosophy and pedagogy.

Closer to home, Maryland hosts school leaders from across the UK who are considering how to promote equality within their schools better. “Many head teachers ask, ‘How do we start to embed equality and equity?’” says Anastasia. “They say, ‘We just don’t think we can do what you do’. So, our answer is always: ‘OK, we’ll show you’.”

So, why is this school special? What does it do to make a difference? Crucially, how can this help other NAHT members answer the ‘how do we start?’ question?

The school’s pioneering approach grew out of two traumatic events: first, the experience of inequality during the covid-19 pandemic and, second, the impact of George Floyd’s murder in the USA.

Lorna explains: “During covid-19, there was a misconception that became an awful rumour, not just locally but nationally, that people of colour were more prone to the disease and even spreading the virus. The East Asian communities were also discriminated against for the same reason.”

Feeling the need to stand up for these communities, she wrote an advisory statement to local schools on how to tackle these rumours and areas of discrimination. After the murder of George Floyd, also in 2020, she was then asked by head teachers in the borough to advise on how best to tackle this traumatic event within schools and the spotlight it shone on inequality and racism.

“So, with two other head teacher colleagues, I created a project called Education4Change,” Lorna tells Leadership Focus. The project was designed to provide training and resources to challenge racism through conversation and curriculum. While this project continues, after two years, Maryland moved on to develop its own equality projects, with its work evolving to encompass all elements of inclusion, diversity and equity.

Research and curriculum tools now cover a wide range of areas of discrimination, such as that based on gender, religion, neurodiversity, body image (for example, hair, facial features, skin tone and conditions such as vitiligo), cerebral palsy, limb difference and other areas, with the school building a wide range of bespoke teaching resources along the way.

Lorna and the Maryland equality team have written research papers and training programmes, including what they believe is a unique racial literacy conversation kit. This is designed to facilitate challenging conversations about discrimination, which we will return to.

Extensive continuing professional development materials have also been created. These outline how to address and embed equality at every level of a school, for example, tackling bias, reviewing the school’s culture and ‘personality’ and addressing the impact of ‘labelling’.

The school has developed a strategic evaluation tool and curriculum audit to identify gaps in policies and procedures. This is designed to help school leaders identify actions and indicate areas of school development that might not otherwise have been considered. Equality and inclusion are embedded in the school’s approach to art, music and history – across the whole curriculum.

Newham Council asked the school to curate a public art exhibition for Black History Month. The exhibition, which runs from October to December each year, showcases the children’s work as installations around the school.

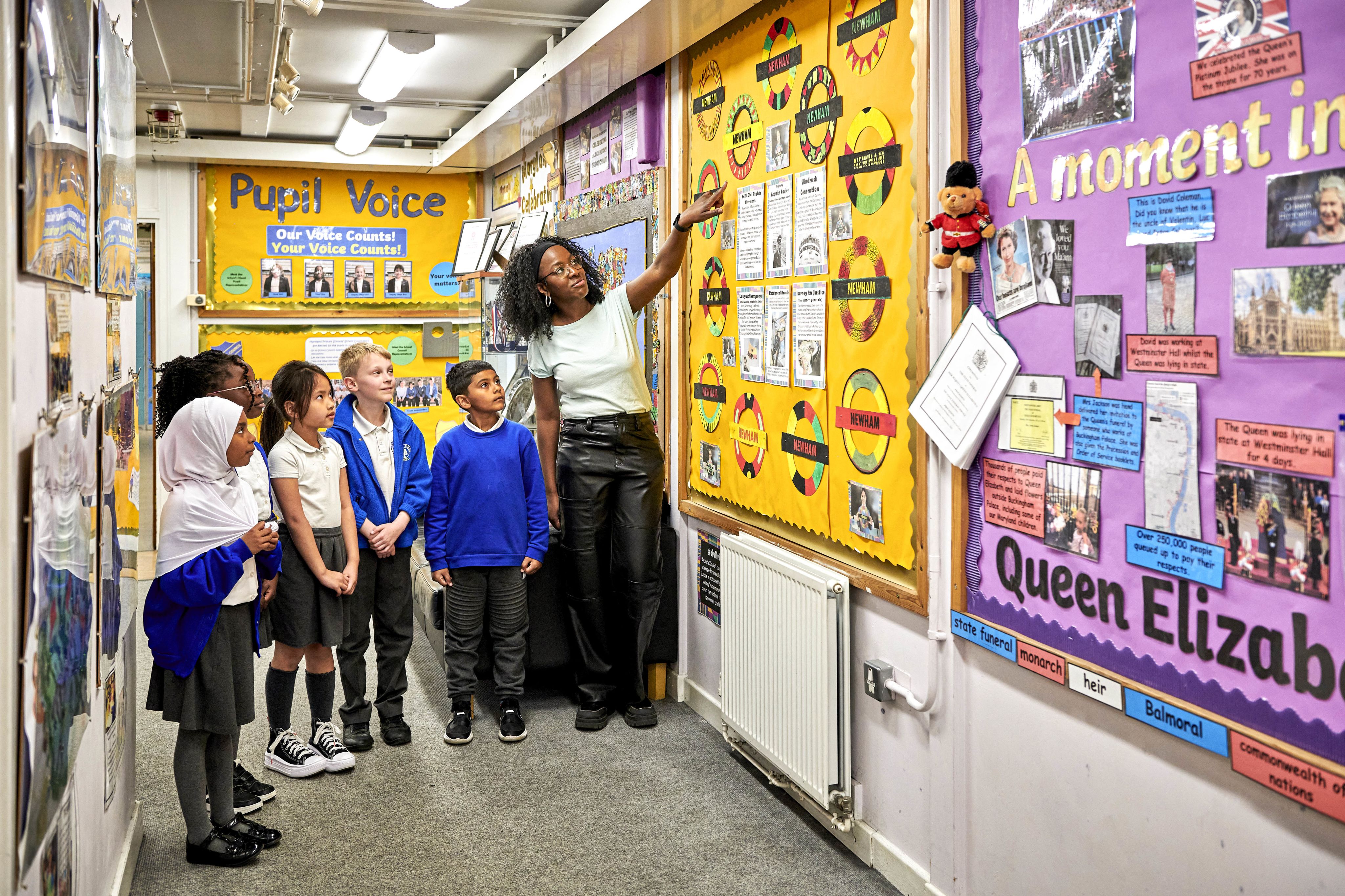

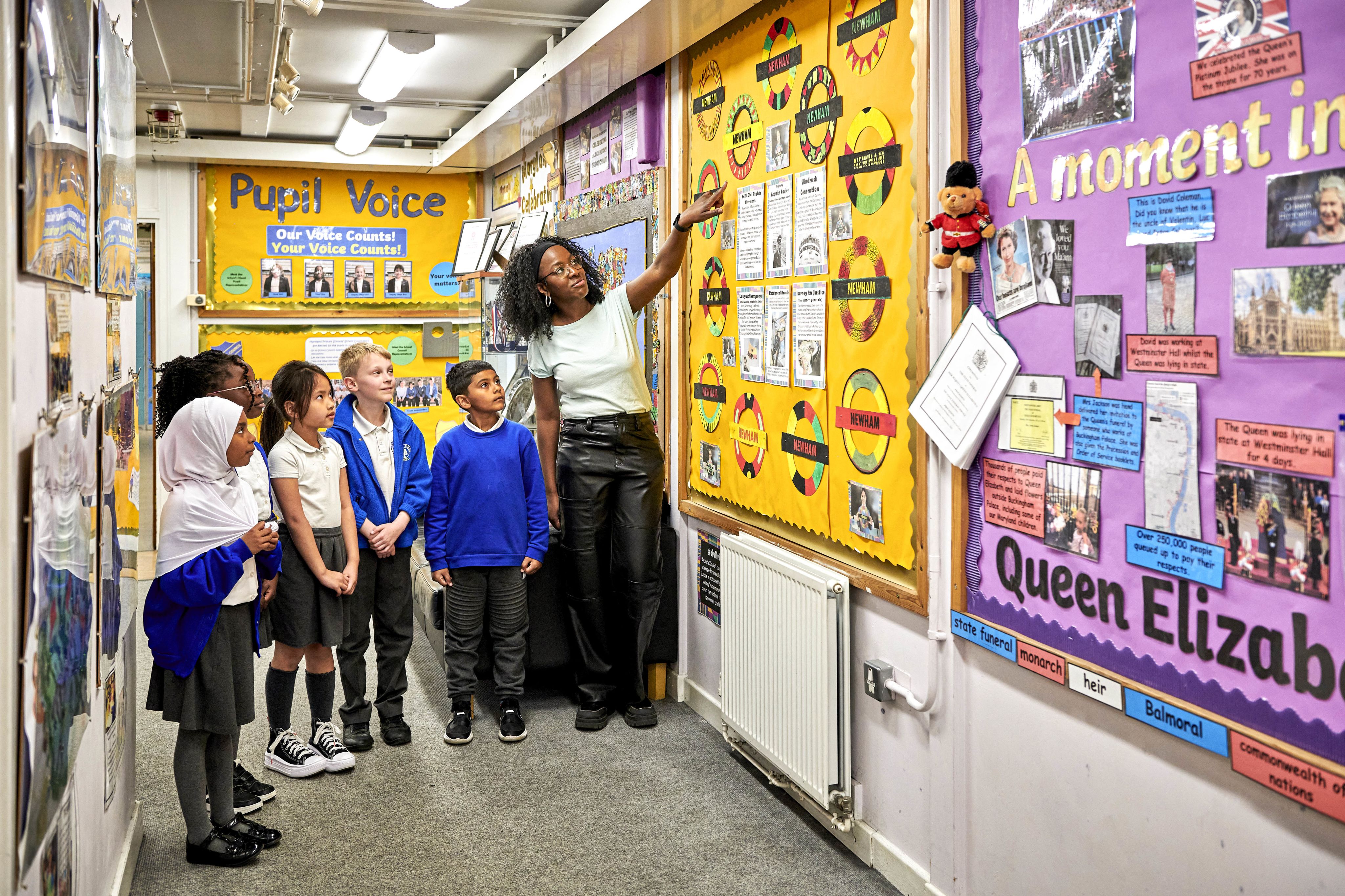

Lorna herself is of Jamaican heritage and part of the Windrush generation – in the late 1950s, both her parents were invited to work in the UK, her father as a train driver and her mother as a nurse. Her heritage and story are used as resources, with a timeline outside her office that follows her journey from a baby in Jamaica to a school leader receiving an MBE, through to attending the state funeral of Queen Elizabeth – and not forgetting becoming NAHT local president.

“We have a mantra displayed in every class and around the school as a reminder that ‘The words you use to a child become their inner voice’ to demonstrate the impact of language. Interestingly, parents tell us children are teaching them about equality at home!” she explains.

Another of Maryland’s mantras is ‘I’m proud to be me’. Lorna emphasises that this is displayed around the school as a visible reminder of the important message that we are all unique and should be proud to be so. “This empowers children to strengthen their self-confidence, courage and resilience, particularly when faced with the challenges of the modern age,” she says.

Lorna explains: “During covid-19, there was a misconception that became an awful rumour, not just locally but nationally, that people of colour were more prone to the disease and even spreading the virus. The East Asian communities were also discriminated against for the same reason.”

Feeling the need to stand up for these communities, she wrote an advisory statement to local schools on how to tackle these rumours and areas of discrimination. After the murder of George Floyd, also in 2020, she was then asked by head teachers in the borough to advise on how best to tackle this traumatic event within schools and the spotlight it shone on inequality and racism.

“So, with two other head teacher colleagues, I created a project called Education4Change,” Lorna tells Leadership Focus. The project was designed to provide training and resources to challenge racism through conversation and curriculum. While this project continues, after two years, Maryland moved on to develop its own equality projects, with its work evolving to encompass all elements of inclusion, diversity and equity.

Research and curriculum tools now cover a wide range of areas of discrimination, such as that based on gender, religion, neurodiversity, body image (for example, hair, facial features, skin tone and conditions such as vitiligo), cerebral palsy, limb difference and other areas, with the school building a wide range of bespoke teaching resources along the way.

Lorna and the Maryland equality team have written research papers and training programmes, including what they believe is a unique racial literacy conversation kit. This is designed to facilitate challenging conversations about discrimination, which we will return to.

Extensive continuing professional development materials have also been created. These outline how to address and embed equality at every level of a school, for example, tackling bias, reviewing the school’s culture and ‘personality’ and addressing the impact of ‘labelling’.

The school has developed a strategic evaluation tool and curriculum audit to identify gaps in policies and procedures. This is designed to help school leaders identify actions and indicate areas of school development that might not otherwise have been considered. Equality and inclusion are embedded in the school’s approach to art, music and history – across the whole curriculum.

Newham Council asked the school to curate a public art exhibition for Black History Month. The exhibition, which runs from October to December each year, showcases the children’s work as installations around the school.

Lorna herself is of Jamaican heritage and part of the Windrush generation – in the late 1950s, both her parents were invited to work in the UK, her father as a train driver and her mother as a nurse. Her heritage and story are used as resources, with a timeline outside her office that follows her journey from a baby in Jamaica to a school leader receiving an MBE, through to attending the state funeral of Queen Elizabeth – and not forgetting becoming NAHT local president.

“We have a mantra displayed in every class and around the school as a reminder that ‘The words you use to a child become their inner voice’ to demonstrate the impact of language. Interestingly, parents tell us children are teaching them about equality at home!” she explains.

Another of Maryland’s mantras is ‘I’m proud to be me’. Lorna emphasises that this is displayed around the school as a visible reminder of the important message that we are all unique and should be proud to be so. “This empowers children to strengthen their self-confidence, courage and resilience, particularly when faced with the challenges of the modern age,” she says.

SABRINA CHARLERY,

EQUALITY LEAD TEACHER, MARYLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL

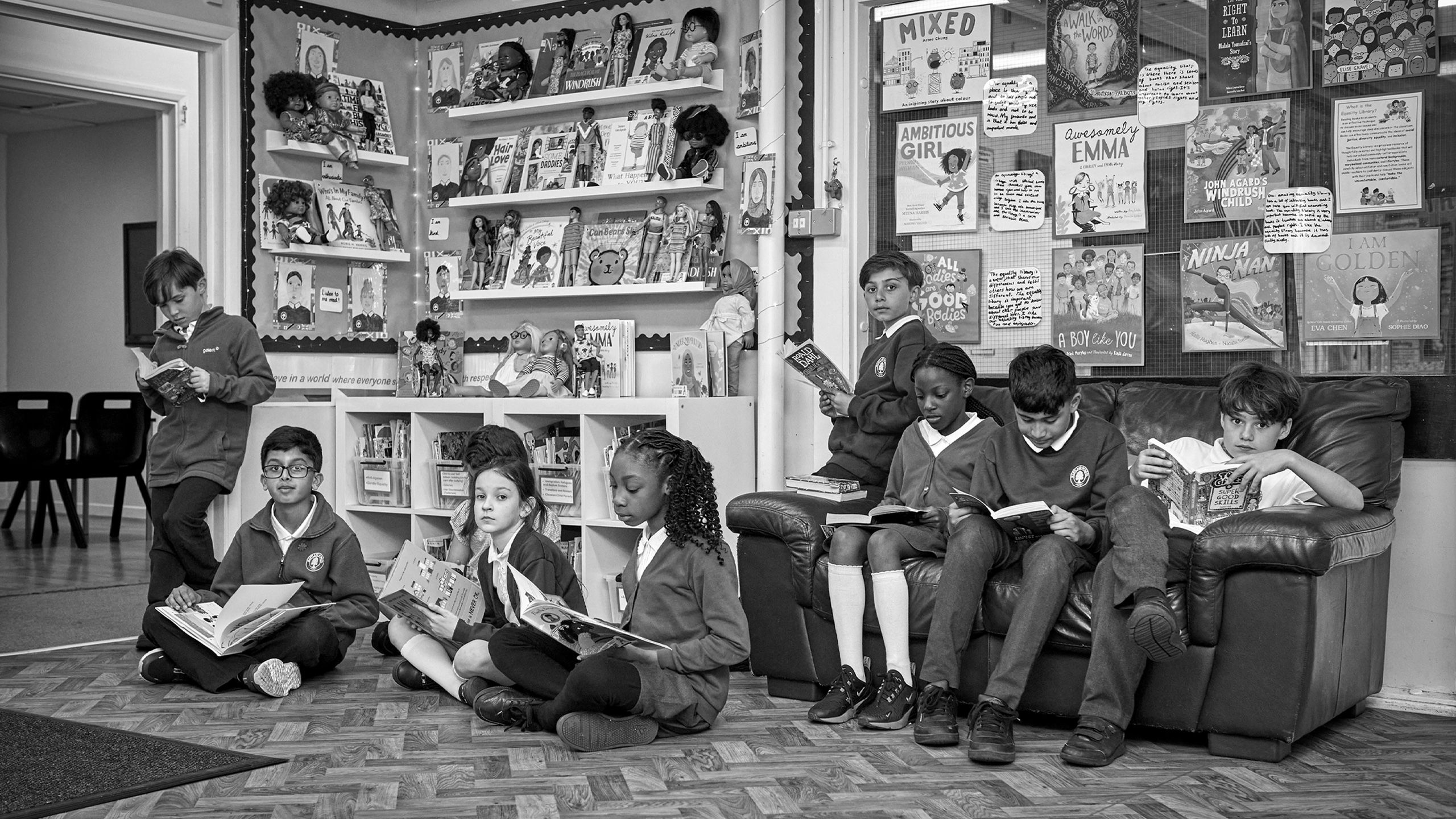

The school has a designated equality lead teacher, Sabrina Charlery. As part of her role, she leads on researching and writing teacher guidance for the school’s dedicated equality library. The equality library is another unique resource within the school. It comprises books with powerful messages to equip teachers with the tools and language to have, as Lorna puts it, “courageous, confident and sensitive conversations” around equality.

In addition to books, the library is supplemented with dolls that represent ‘uniqueness’. These are designed to work as an engaging way to support teachers in having conversations with children about representation.

SABRINA CHARLERY,

EQUALITY LEAD TEACHER, MARYLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL

The school has a designated equality lead teacher, Sabrina Charlery. As part of her role, she leads on researching and writing teacher guidance for the school’s dedicated equality library. The equality library is another unique resource within the school. It comprises books with powerful messages to equip teachers with the tools and language to have, as Lorna puts it, “courageous, confident and sensitive conversations” around equality.

In addition to books, the library is supplemented with dolls that represent ‘uniqueness’. These are designed to work as an engaging way to support teachers in having conversations with children about representation.

For example, there are dolls with limb differences, vitiligo, varying skin tones, albinism, alopecia, different hair textures, hearing aids, glasses, cultural styles and so on. There are dolls, too, to represent children of mixed heritage, a significant population of the school.

Anastasia gives the example of a 10-year-old boy who picked up and began playing with a doll representing mixed heritage, saying: “At last, a doll that looks just like me”. “It was very powerful,” she adds.

“Assemblies are an effective tool for teaching a simple message around equality,” Anastasia adds. “Every Monday, we have a whole-school assembly where Lorna or I will set out a message or a theme of the week.

“This will then be shared with the staff, giving teachers the opportunity to discuss the message in class with their children. Each assembly is linked to a book, visitor, song or short video, so the delivery is always exciting, enriching and lively.”

“We write guidance for assemblies and slide presentations for all ages, with topics ranging from fairness to justice but always linked to something topical and relevant to the children, such as football,” agrees Lorna.

“We were looking for an assembly on sun safety that talked about the science of melanin and its role in protecting the skin from the sun. We could not find an assembly out there that mentioned melanin as a protection, so we designed one, and then we were asked to share it with primary schools in the borough for Sun Safety Week.

“Every year, on 22 June, we celebrate Windrush Day. Learning about the Windrush generation’s contribution to Britain is part of our history and should be taught regardless of a school’s demography. We designed the Caribbean menu used by most Newham schools to acknowledge the day,” Lorna adds.

For example, there are dolls with limb differences, vitiligo, varying skin tones, albinism, alopecia, different hair textures, hearing aids, glasses, cultural styles and so on. There are dolls, too, to represent children of mixed heritage, a significant population of the school.

Anastasia gives the example of a 10-year-old boy who picked up and began playing with a doll representing mixed heritage, saying: “At last, a doll that looks just like me”. “It was very powerful,” she adds.

“Assemblies are an effective tool for teaching a simple message around equality,” Anastasia adds. “Every Monday, we have a whole-school assembly where Lorna or I will set out a message or a theme of the week.

“This will then be shared with the staff, giving teachers the opportunity to discuss the message in class with their children. Each assembly is linked to a book, visitor, song or short video, so the delivery is always exciting, enriching and lively.”

“We write guidance for assemblies and slide presentations for all ages, with topics ranging from fairness to justice but always linked to something topical and relevant to the children, such as football,” agrees Lorna.

“We were looking for an assembly on sun safety that talked about the science of melanin and its role in protecting the skin from the sun. We could not find an assembly out there that mentioned melanin as a protection, so we designed one, and then we were asked to share it with primary schools in the borough for Sun Safety Week.

“Every year, on 22 June, we celebrate Windrush Day. Learning about the Windrush generation’s contribution to Britain is part of our history and should be taught regardless of a school’s demography. We designed the Caribbean menu used by most Newham schools to acknowledge the day,” Lorna adds.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

Leadership Focus visited Maryland in May, following visits by NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman and NAHT senior equalities officer Natalie Arnett. There is a strong sense of calm and nurturing, with children able to access an award-winning outdoor environment (including ‘Cluckingham Palace’, which houses the school’s beloved hens, a ‘Nature’s Garden’ with a polytunnel that grows exotic produce and even a manufactured beach area emulating the famous ‘Negril Beach’ in the Caribbean).

“It is a fabulous place; it knocks your socks off when you go there,” NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman recalls of his own visit. “The whole team is absolutely wedded to the school’s ambition, objectives and ethos; you can feel it in everything they do.

“NAHT members ‘get’ this stuff; they deal with it every week, every day. Their pursuit of inclusion for the young people in their care is relentless. But what is very important is we also wrap this into the wider, bigger issues we face as a union,” he adds.

“Why do we do this?” questions Anastasia. “We see equality as a safeguarding issue because discrimination has a significant impact on a child’s life chances, self-esteem and safety.

NATASHA ST ROSE,

ASSISTANT HEAD TEACHER, MARYLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL

“One of our assistant head teachers, Natasha St Rose, wrote a guidance document on adultification, which was shared with all the safeguarding leads in the borough and the NSPCC. Equality is so vast because it has to be interwoven into everything you do; it cannot just be an add-on. We have not waited for government policy or guidance; we know that it is imperative we equip our children with the tools to challenge inequality and discrimination,” Anastasia adds.

BIANCA JAMES,

TEACHING AND LEARNING LEADER, MARYLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL

Teaching and learning leader Bianca James continues: “Although we have found the best way to embed equality messages is through books, these must, of course, be carefully vetted and agreed on as good teaching tools before being placed in our equality library.

“We started, as Lorna has said, by looking at race but, since then, we have evolved our approach to look at both seen and unseen issues that may not be spoken about but impact our children’s lives – for example, child poverty; this is something a lot of our children have experienced, particularly since lockdown, so we explore this sensitively by using the book ‘The Invisible’ by Tom Percival,” she points out.

The role of consistent and focused leadership is, of course, essential in driving forward this agenda, as Lorna emphasises.

“I have a shared vision that I present every year to the whole staff. I call it my ‘state of the nation’ address,” she explains.

“The creation of the equality team, including governors, is imperative because you can’t just stand alone and wave a flag. In a way, the whole staff is the equality team because we all demonstrate an agreed philosophy and convey the same message.

“We also teach children about their uniqueness. We make sure the children understand that their uniqueness and diversity are powerful rather than just inclusion. Inclusion is important for belonging and that sense of security. However, celebrating our uniqueness (difference) is just as important. Now the children feel confident in whoever they are,” Lorna adds.

The school encourages visits from what Lorna calls ‘real models’ as opposed to ‘role models’. These have included inspirational meetings with Sir Lenny Henry, astronaut Tim Peake, authors Patrice Lawrence and Pippa Goodhart and illustrator Dapo Adeola, among others.

Language, too, is vitally important, bringing us back to the racial literacy conversation kit. As Lorna explains: “For example, we speak about ‘heritage’ more than ‘race’, ‘uniqueness’ alongside ‘difference’ and ‘skin tone’ preferably to ‘skin colour’, although I do refer to ‘people of colour'. I also use ‘enslaved people’ rather than ‘slaves’.”

The racial literacy conversation kit, used as a key staff training tool, is based on a survey with several local schools and community advisors to explore a shared understanding of certain terms. It is colour-coded, with red, amber and green sections. ‘Red’ words are those deemed offensive in the UK, for example, describing people as ‘coloured’ or ‘half-caste’. ‘Amber’ words can depend on the context. For example, Lorna points out that ‘West Indian’ is more acceptable when referring to the cricket team or group of islands, but ‘Caribbean’ is preferred when describing people. Examples of ‘green’ words would include ‘British Caribbean’, ‘mixed race’ or someone of ‘mixed heritage’. There is also a very lengthy, helpful glossary of equality terms.

Finally, what of the ‘how to start?’ question, as highlighted by Anastasia at the beginning of this article? And what should NAHT members be taking away from Maryland’s approach and experience?

“Your starting point is your equality statement,” emphasises Anastasia. “That is the legal framework you work within and the demographics of your school. The statement must be published on your website and updated at least every four years. Here, we review it every time we carry out a school census, approximately every three months.

“Beyond that, we make it everyone’s business. Equality is included in our parent newsletters and weekly staff bulletins; it is a standing item on governing board meetings. We include it on our school’s admission form so that every family signs a commitment to equality. Our equality link governor holds us to account,” she adds.

“Our school motto is ‘Maryland School: Where our children’s future matters most’,” adds Lorna. “And this vision is to do with our children’s future. But you have to be prepared that it will be a journey; you can’t do it overnight. And my final mantra is ‘Those who say it can’t be done should not disturb the person doing it’.”