Working

hard for

better pay

Ian Hartwright, NAHT head of policy (professional), outlines that while this year’s 5.5% pay increase is a positive step, much more is needed to restore school leaders’ pay and make the profession competitive and sustainable.

IAN HARTWRIGHT,

NAHT HEAD OF POLICY (PROFESSIONAL)

This year’s pay award of 5.5%, while not restoring the pay school leaders have lost over the last 14 years, is still good news for the profession.

It is a step forward because it meets the three tests we set out in our evidence to the School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB). First, it is a pay rise that is higher than consumer price index (CPI) inflation; second, it is higher than wider earnings growth and wider pay settlements across the economy; and third, it includes, at last, some measure of pay restoration.

Since 2010, the real-term value of school leaders’ pay has been eroded by about a fifth (20%).

Assuming that inflation remains at around current levels, this pay award will likely deliver a 1-2% real-term improvement. Therefore, it is a start in correcting the decline we have seen over the past 14 years in the values of teachers’ and school leaders’ salaries.

I’m sure members are well aware that these are arguments we have been making to the STRB and government for some years. In fact, over the last three pay rounds, we’ve worked hard to create a joined-up narrative across our submissions that makes the strongest case possible. The STRB, I am pleased to say, has understood the evidence we have put before it; it has taken a more independent view of what pay should look like, which is positive.

For me, one of the most important things the STRB has understood is the need to address in a balanced way, as it has put it to us, ‘the structural deterioration in the pay of teachers relative to comparable professions and to improve levels of recruitment and retention’. It has been clear that restoring the overall value of teachers’ and school leaders’ pay is more important than trying to pick out or reward individual groups of professionals by phase, subject or location, which is a helpful way forward.

This year’s 5.5% award sits alongside the two immediately previous awards which, combined, come in at 17% overall in the last three years.

Although that doesn’t match the inflation we’ve had, especially since 2022, these awards are recognition that the STRB agrees our pay has been falling further and further behind and is trying to do something about it.

STRB’s

benchmarking

study

One discussion point that has been particularly helpful this year is that the STRB has carried out a benchmarking study, employing a group of analysts to compare the work of teachers and school leaders with professions with a similar level of responsibility and complexity of role.

STRB’s

benchmarking

study

One discussion point that has been particularly helpful this year is that the STRB has carried out a benchmarking study, employing a group of analysts to compare the work of teachers and school leaders with professions with a similar level of responsibility and complexity of role.

That work strongly shows how the competitiveness of pay in the teaching profession – which in many ways is the flip side of pay restoration – has declined alongside the real-term numbers that people see in their pay packets every month.

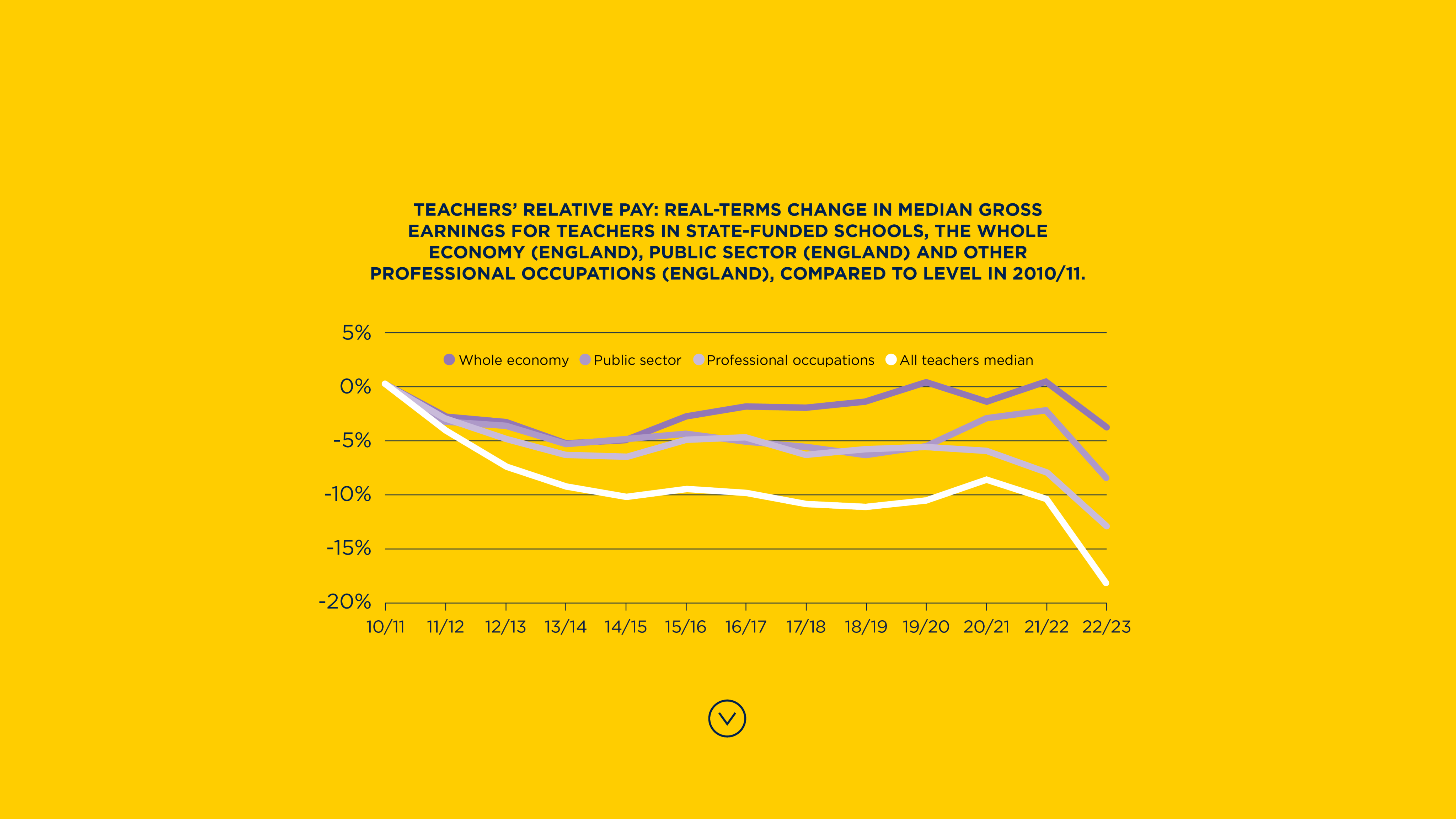

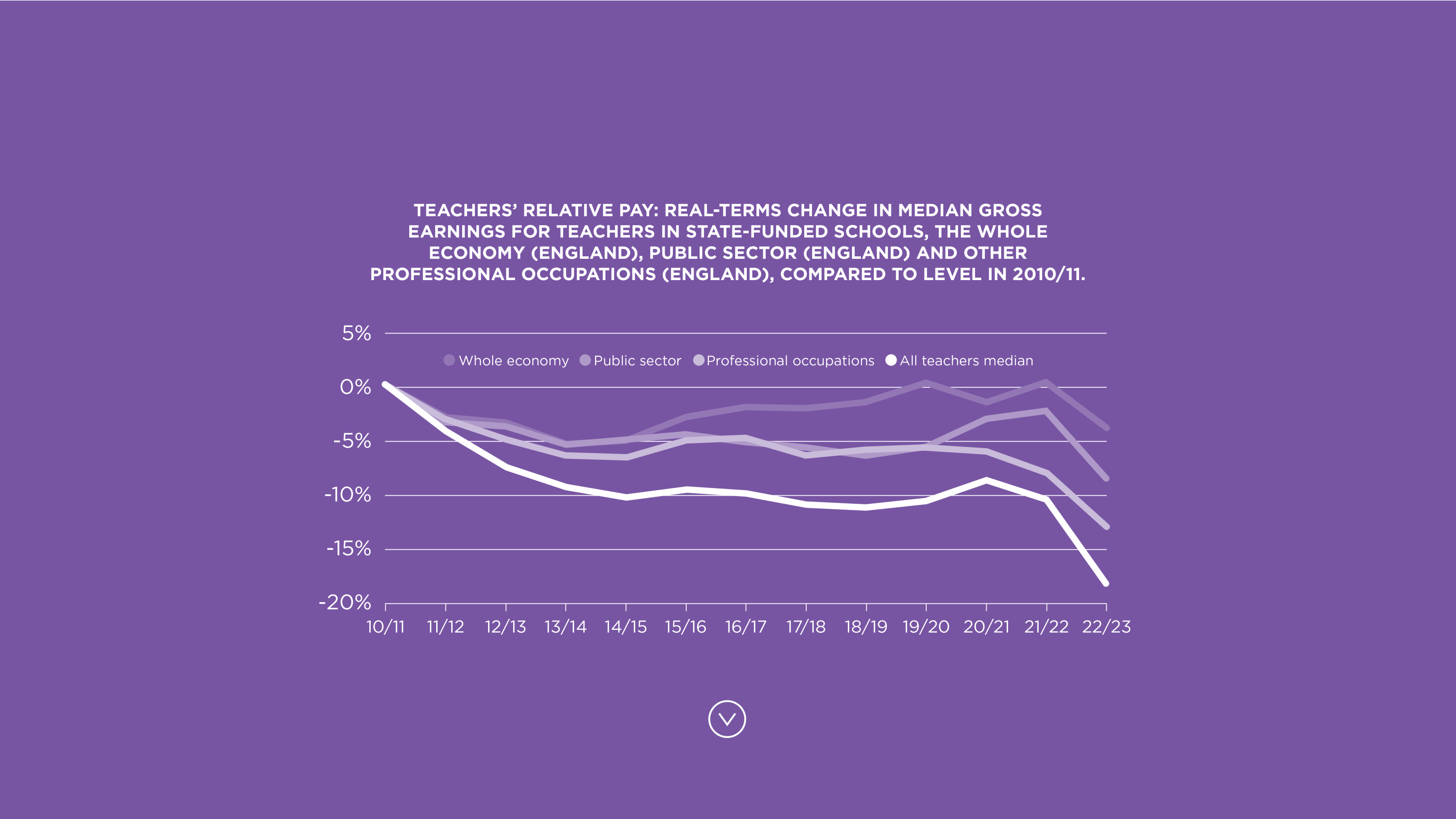

The graph below shows how pay for teaching professionals has declined against other pay in the wider economy. There are a range of different comparators, and teaching is right at the bottom. Essentially, while everyone has become poorer over the last 14 years, relatively speaking teachers have become poorer than other professionals. And school leaders even sit a bit below that.

What is also positive, I think, is that the STRB has understood the qualitative as well as quantitative arguments we have been making – the views and opinions members have taken the trouble to feed in through the panel discussions we have held and the surveys we have carried out.

That real voice of leaders is compelling, and I wish to take this opportunity to thank members who have taken part for giving their time and insight. Completing a survey may not feel much like trade union activism, but I can assure you that it provides critical data to underpin our case.

These arguments are particularly compelling, too, when we talk about leadership aspiration and unpick why people are becoming ever-more reluctant to step up into leadership roles. Worryingly, our data shows that currently, 61% of deputy and assistant head teachers – the highest percentage we have ever recorded – now say they don’t intend or want to become a head teacher.

There are three factors at work here. One is the implicit career risk of high-stakes accountability – in other words, the fear of the consequence of taking sole responsibility for a school and the risk that poses to your job if Ofsted comes along and gives you an unhelpful judgement.

Second is the punishing workload that comes with school leadership and, particularly, the impact that can have on health; increasingly, leaders see those two things as connected. Then, the third factor is pay. The pay differential is simply not enough to make it worth taking that risk of accountability and that risk to your health.

This is a particular issue we continue to find with leadership and headship roles in smaller schools. Particularly for a deputy head teacher working in a large primary school, your first step into headship may be through a move to a much smaller school, at least initially.

However, in that scenario, you take on all the responsibility, you probably take on more leadership jobs because there is less leadership distribution and delegation and, on top of that, you finish up with little in the way of extra money. Sometimes, in fact, you may even be on lower pay than you were before. There is a structural issue we strongly feel needs addressing, which I shall return to later in this article.

Roles and salaries vs responsibility and weight of role

A second useful piece of work the STRB carried out this year is that it evaluated the roles and salaries of school leaders against the responsibility and weight for that role and, again, compared that against broadly similar professions and roles.

Roles and salaries vs responsibility and weight of role

A second useful piece of work the STRB carried out this year is that it evaluated the roles and salaries of school leaders against the responsibility and weight for that role and, again, compared that against broadly similar professions and roles.

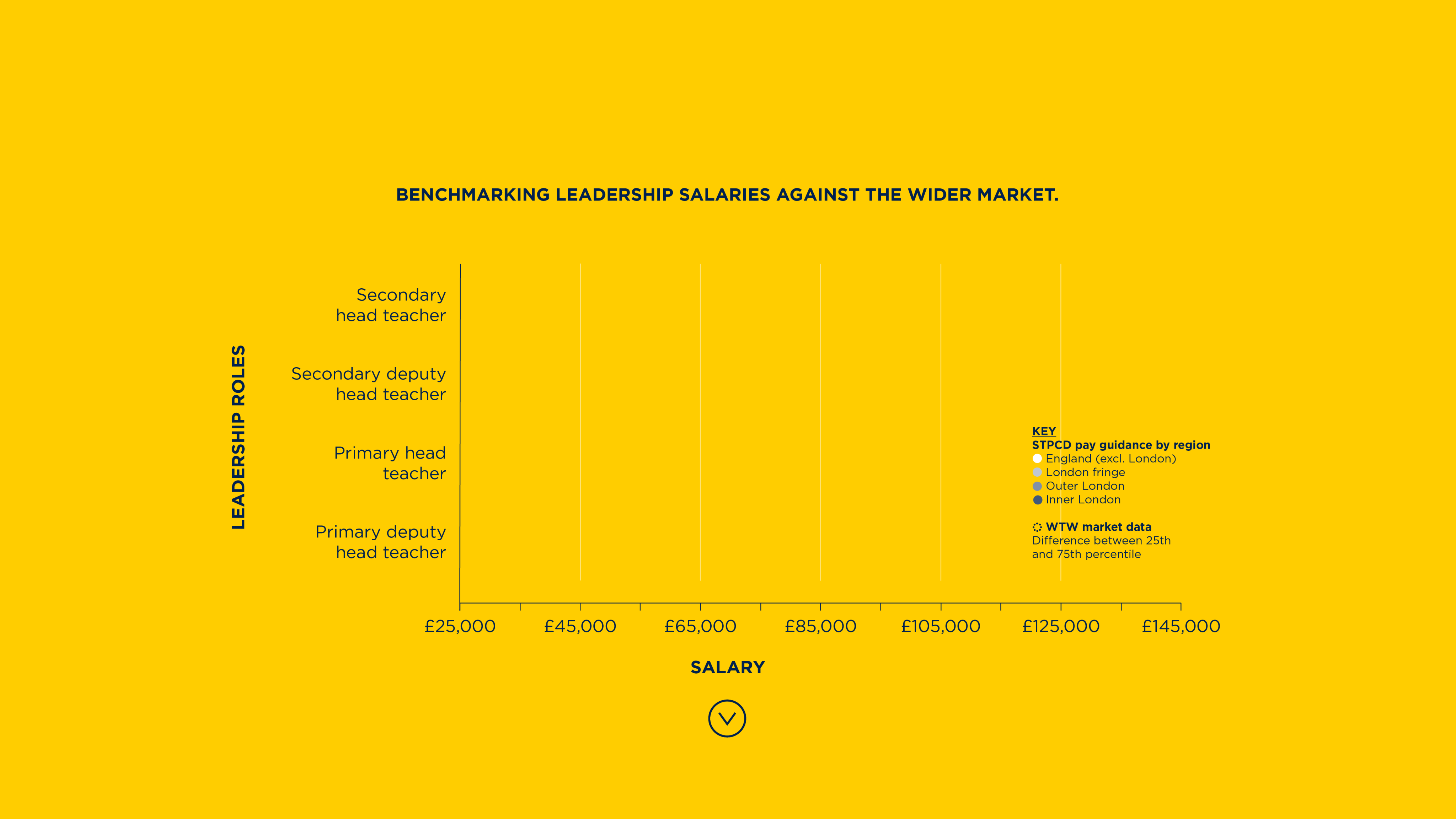

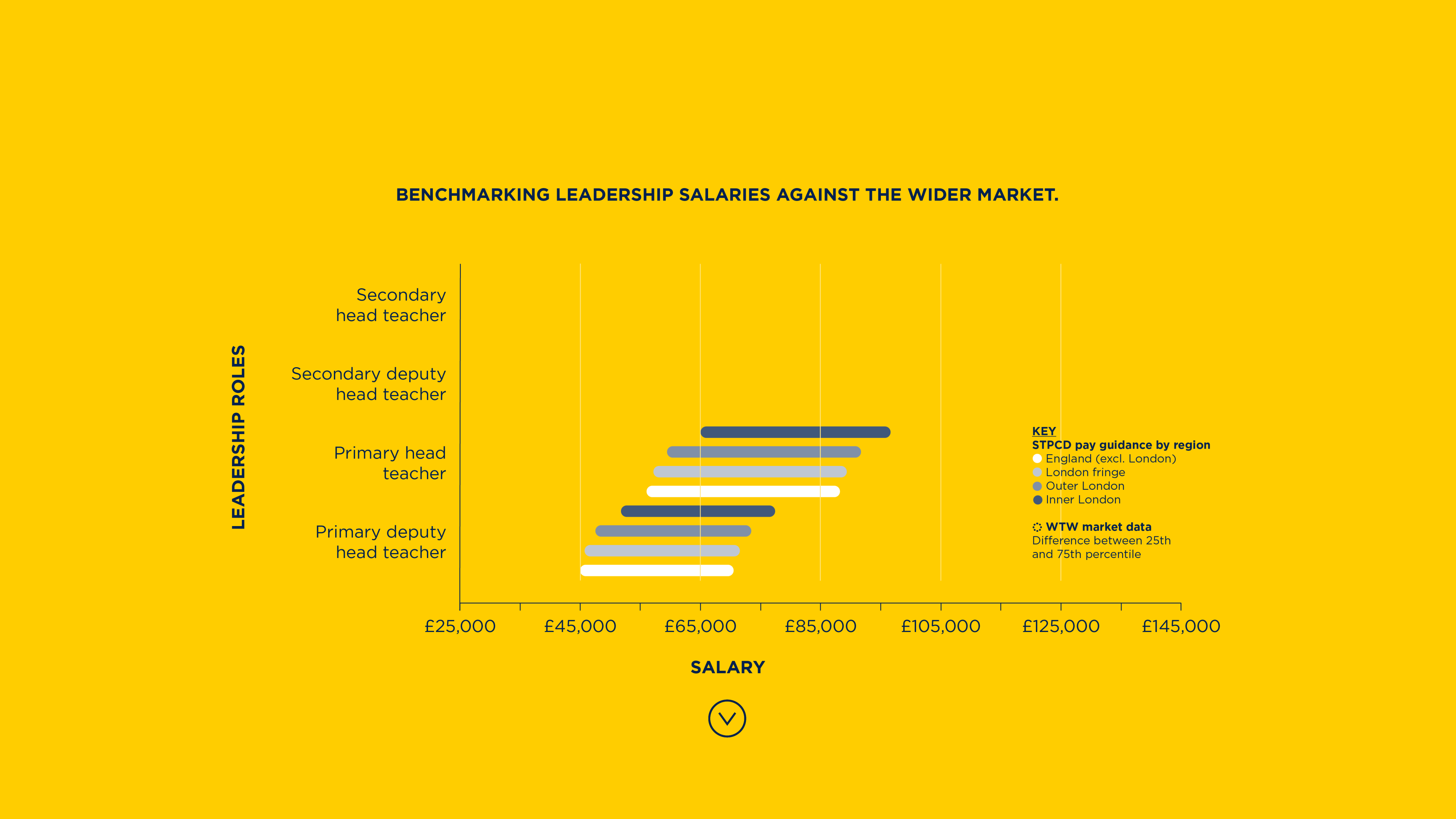

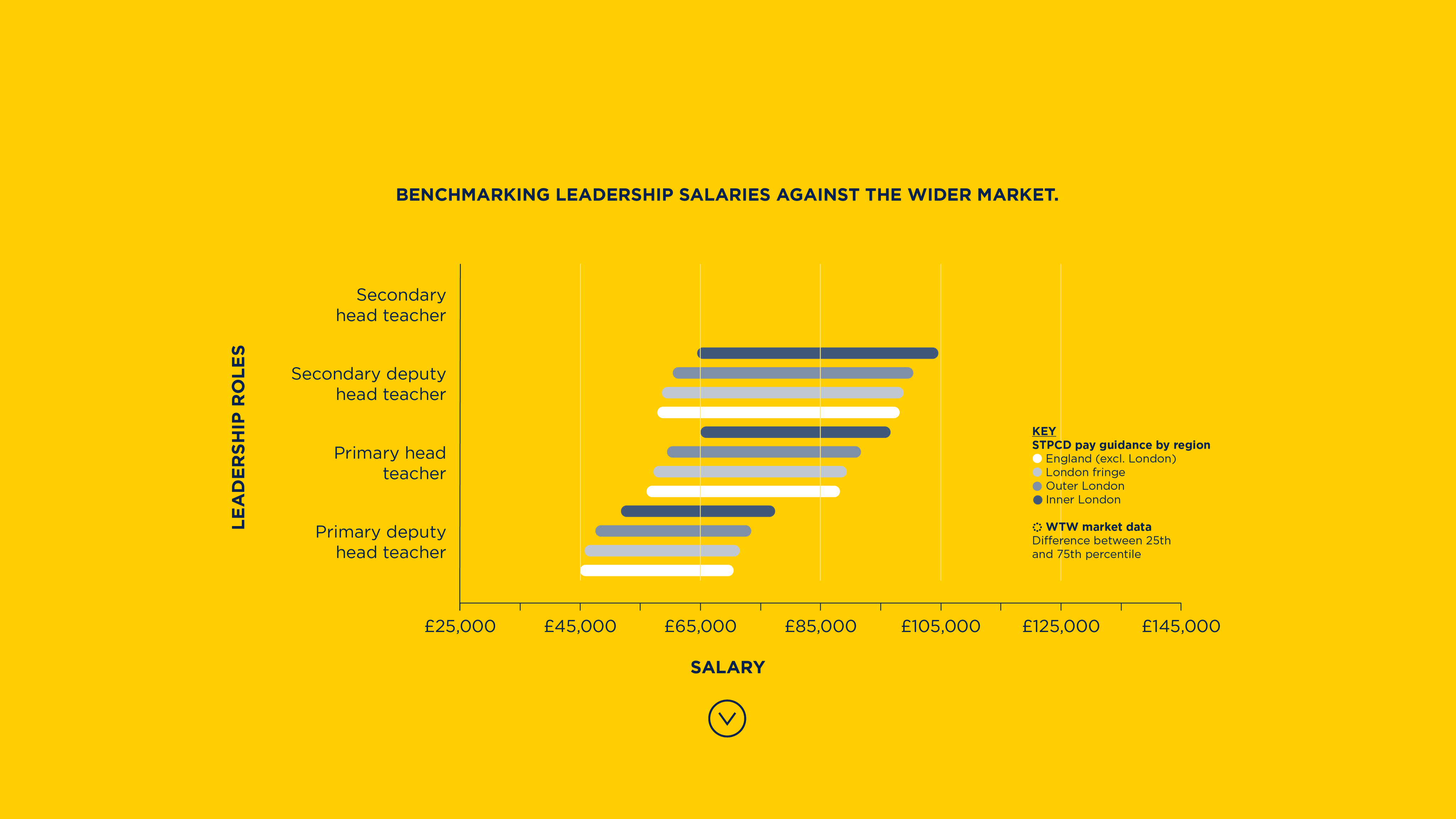

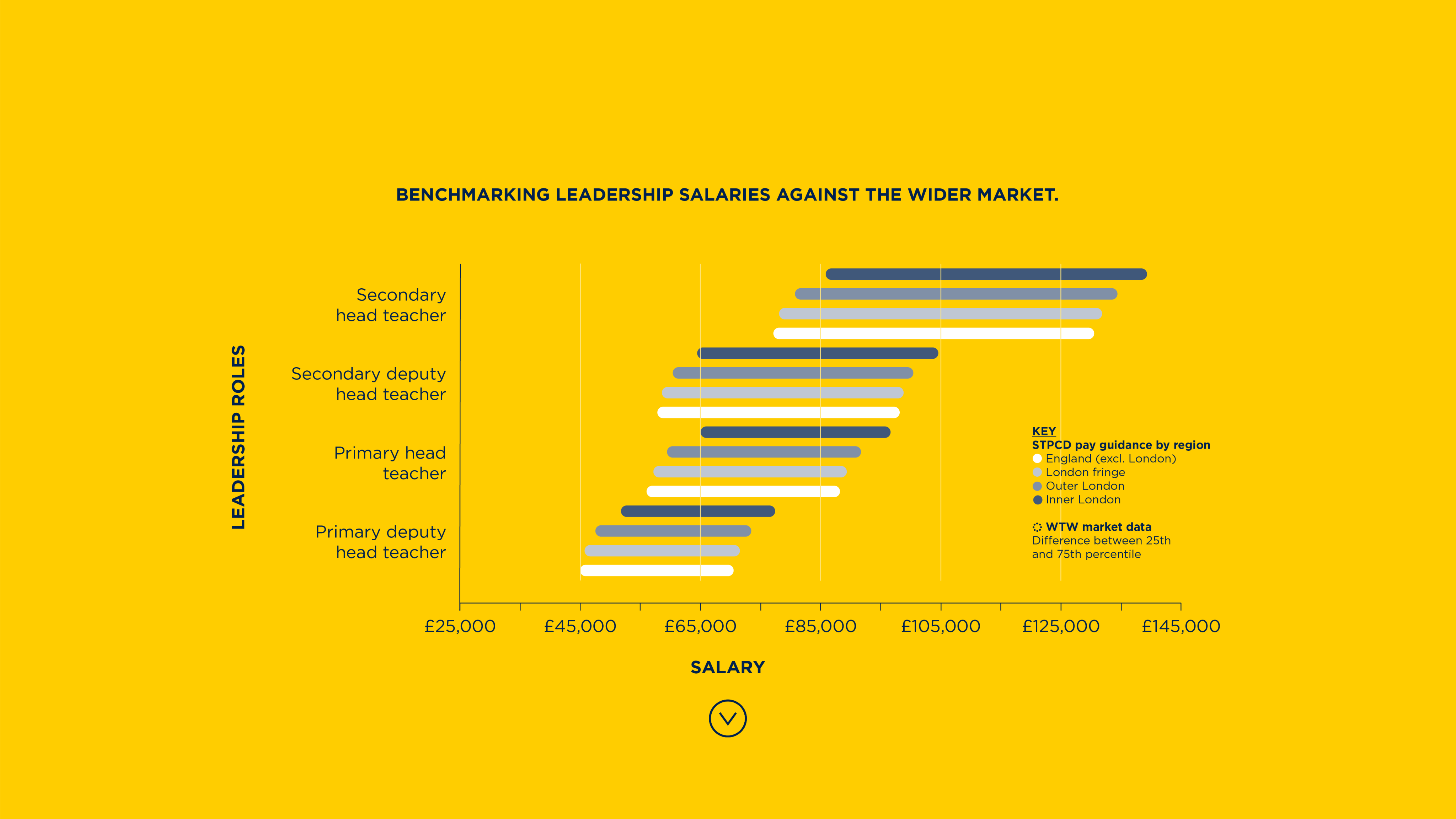

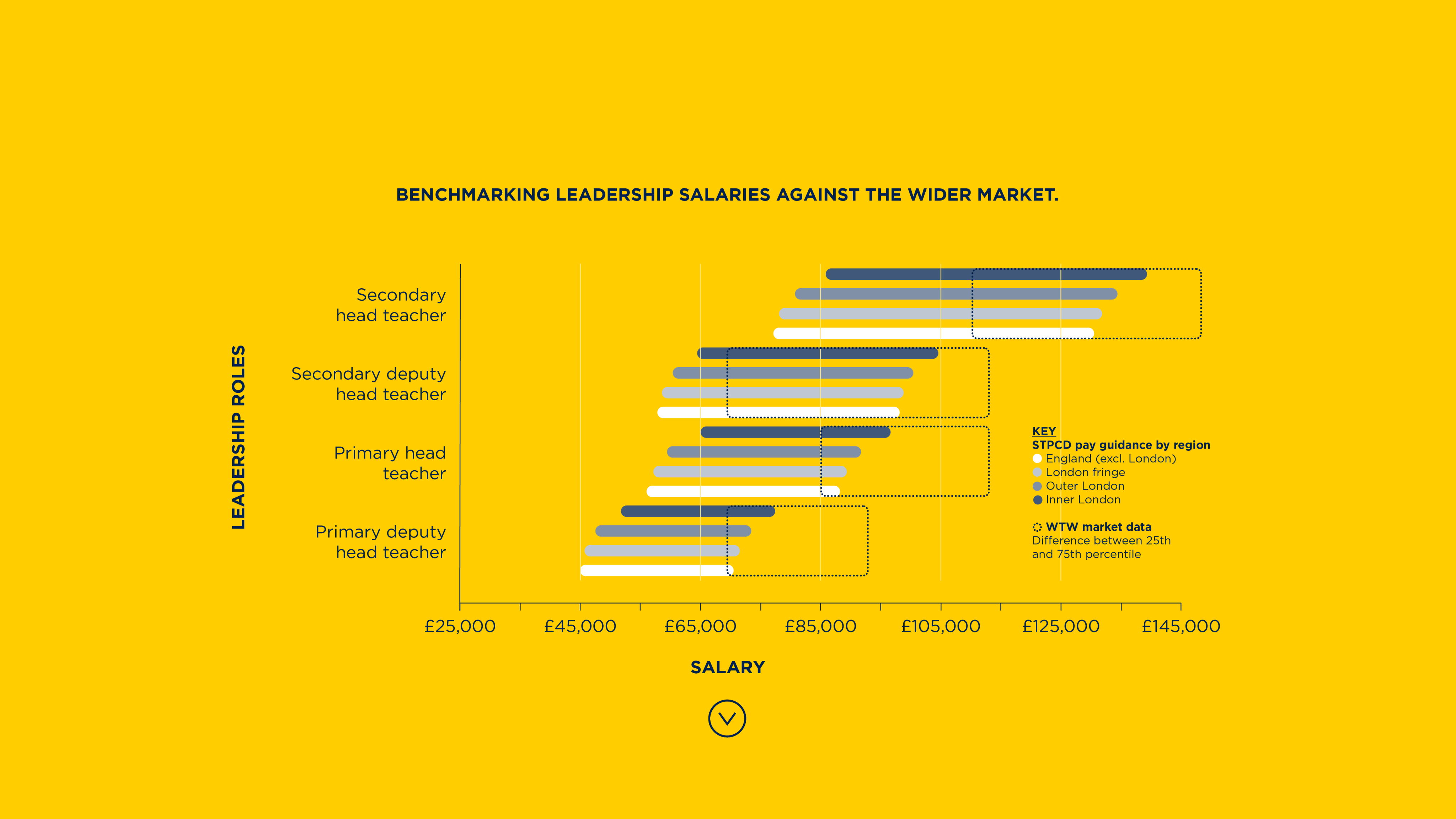

As shown in the diagram below, it’s complex, so let me explain. The four coloured horizontal bars show the salary range for head teachers and deputy head teachers in secondary and primary schools outside London and within the three London salary zones. The boxes show a range of salaries for roles outside teaching identified as broadly comparable in size and scope at various career stages.

What this graphic shows, therefore, is that primary roles – especially the primary deputy head teacher role – barely align with what they should or would be in a comparable role outside of education; they barely even make it to the start line, in fact. Essentially, if you are doing a job of similar size, scope and complexity in another sector, you will be paid more – sometimes much more – than you would get in a primary school. The differential is less at the secondary level but is still clearly there.

The years of pay stagnation show us that, as a society, we have increasingly come to undervalue the work that school leaders do, especially primary school leaders. We consistently underappreciate how complex and difficult those roles are and how responsible and weighty they are.

So, to return to my opening line that this year’s 5.5% rise is ‘good news’ for the profession: it is, but it needs to be just the start.

We very much hope it will be just the first of more positive moves in the coming pay rounds. We need to persuade the STRB that, over the course of this parliament, we should see genuine pay restoration that recoups the real-term value of leaders’ salaries.

How likely is the STRB to recommend this, given the wider challenging fiscal situation this government faces? In the past, we have been very critical of the STRB for not exercising its independence to make recommendations beyond the government’s pay freeze or cap.

However, positively, what we have seen in the last three years – so even before the change of the government – is the STRB asserting its independence much more strongly, going beyond the boundaries the government has set for it. It seems to me that the STRB is keen to make its own, more independent decisions now.

In many respects, that’s only as it should be. The purpose of a pay review body is to take the ‘heat and light’ out of the industrial process and reduce the complexity of the bargaining needed in a scenario, as there is with teaching, where there are many different employers.

What this graphic shows, therefore, is that primary roles – especially the primary deputy head teacher role – barely align with what they should or would be in a comparable role outside of education; they barely even make it to the start line, in fact. Essentially, if you are doing a job of similar size, scope and complexity in another sector, you will be paid more – sometimes much more – than you would get in a primary school. The differential is less at the secondary level but is still clearly there.

The years of pay stagnation show us that, as a society, we have increasingly come to undervalue the work that school leaders do, especially primary school leaders. We consistently underappreciate how complex and difficult those roles are and how responsible and weighty they are.

So, to return to my opening line that this year’s 5.5% rise is ‘good news’ for the profession: it is, but it needs to be just the start.

We very much hope it will be just the first of more positive moves in the coming pay rounds. We need to persuade the STRB that, over the course of this parliament, we should see genuine pay restoration that recoups the real-term value of leaders’ salaries.

How likely is the STRB to recommend this, given the wider challenging fiscal situation this government faces? In the past, we have been very critical of the STRB for not exercising its independence to make recommendations beyond the government’s pay freeze or cap.

However, positively, what we have seen in the last three years – so even before the change of the government – is the STRB asserting its independence much more strongly, going beyond the boundaries the government has set for it. It seems to me that the STRB is keen to make its own, more independent decisions now.

In many respects, that’s only as it should be. The purpose of a pay review body is to take the ‘heat and light’ out of the industrial process and reduce the complexity of the bargaining needed in a scenario, as there is with teaching, where there are many different employers.

Setting out a timetable for the pay process

The STRB has also stated that it wants the government to set out a clear timetable for the pay process and to stick to it so that pay decisions are made in a timely manner.

Setting out a timetable for the pay process

The STRB has also stated that it wants the government to set out a clear timetable for the pay process and to stick to it so that pay decisions are made in a timely manner.

Promisingly, new ministers seem equally keen to achieve this. The government has failed to submit its evidence on time for the last eight years. So, having a proper timetable that everyone adheres to would be a real step forward.

As usual, this year’s pay remit will cover a single year. We are, however, pressing for a move to a multi-year pay remit, covering perhaps two to three years, with two or three pay uplifts already set out.

This would have several advantages, although you would need to build in some kind of safety mechanism in case inflation rises sharply. You would have a bit more surety around finance. Of course, the uplifts would need to be fully funded – otherwise, they would be unaffordable. Schools would then be able to budget for two to three years and better manage their staff costs. There wouldn’t be any of that messing around late in the summer or even in September trying to reset the budget.

It is really important that the government does not think it has ‘done the job’ just because it has accepted a recommendation of an above-inflation uplift this year. We will apply the same tests we used this year to next year’s settlement. So, to recap, it will need to be above CPI inflation and above pay rises in the wider economy, and a measure of pay restoration will need to be delivered.

To restore the eroded pay of teachers and school leaders by the end of this parliament would require real-term rises of about 4% to 5% each year.

That, we do appreciate, is quite a big ask, given the wider fiscal situation. However, we strongly believe the ambition should at least be to return teachers’ pay to where it was pre-2010. That would restore our pay competitiveness and make teaching look and feel a much better place.

Making teaching more attractive and sustainable as a career and profession

Beyond that – and yes, again, I appreciate this is ambitious – we would really like to see a joined-up package of pay- and non-pay-related measures designed to make teaching more attractive and sustainable as a career and a profession.

Making teaching more attractive and sustainable as a career and profession

Beyond that – and yes, again, I appreciate this is ambitious – we would really like to see a joined-up package of pay- and non-pay-related measures designed to make teaching more attractive and sustainable as a career and a profession.

A multi-year remit would provide the time and space to review and redesign the pay structure across the profession. That needs to be done concurrently for teachers and school leaders; you can’t separate the two. This must also specifically address the situation facing school leaders of small schools, as I highlighted earlier.

We urgently need to reconsider the factors that define leadership pay, codify the various executive leadership roles with a revised school teachers’ pay and conditions document (STPCD) and align school business leadership roles with the leadership pay range. We need a national pay structure with mandatory minimum pay points applied across all state-funded schools. So, every teacher at a particular level of experience will know the minimum they should be paid.

There should also be pay portability to improve teachers’ and school leaders’ mobility across the system. So, if you are an M5 teacher and want to move schools somewhere, then you should be paid M5 (again as a minimum) for doing that; you shouldn’t have to have a pay negotiation around that. That, we believe, would create a much more level playing field across the whole structure.

Work is needed to deliver better career pathways to make teaching and school leadership more attractive career options, alongside strategies to support teachers and school leaders into their later careers so that we retain experience within the profession.

Alongside that, we need to build a compelling career proposition for teaching, and this is perhaps where there is scope for innovative thinking. There needs to be thinking around finding new flexibilities for teachers at all career stages and creative solutions that do not necessarily involve pay directly.

It could be things such as funded travel cards for teachers working in London. Or a fixed number of well-being days that can be taken within term time. Or the option of taking a sabbatical after a period of service. Or the restoration of relocation allowances. Or better promotion of pension benefits. Or phased or full student loan redemption; for example, the incentive of having your student loan paid off after completing 10 years of service.

That loan conversation, coupled with workload reduction strategies, could be a game changer for retention. It would immediately increase professionals’ disposable incomes, which would then feed through into boosting the wider economy: housing, consumer spending, and so on.

Maintaining the momentum

To conclude, I think we’re at a really interesting inflexion point. We have made real progress with the STRB on teachers’ and school leaders’ pay, but that momentum now needs to continue.

Maintaining the momentum

To conclude, I think we’re at a really interesting inflexion point. We have made real progress with the STRB on teachers’ and school leaders’ pay, but that momentum now needs to continue.

We’re hopeful that the STRB taking a more independent approach, along with a new government in power that is keen to work in social partnership – rather than at loggerheads – with representative trade unions, could bring about real change.

As I have outlined, some of these changes are structural, and some may require creative thinking and solutions. Not all will necessarily involve money needing to be thrown at them.

It is early days, but I am hopeful that we will be able to establish different, more open and more constructive conversations with the government and officials over the coming months.

Ultimately, I hope a 5.5% uplift is just the start of a process of much more profound, positive change.

Update: NAHT’s campaign and evidence submission

The challenge of restoring the value and competitiveness of leaders’ pay remains a key campaign area for NAHT. Just before Christmas, NAHT submitted evidence to the STRB in the first part of this year’s pay round.

You may have seen that the government’s evidence suggests the STRB should recommend an unfunded uplift of 2.8%. By contrast, NAHT’s evidence makes a powerful case that the STRB should recommend an annual uplift for each year of this parliament that is higher than average pay settlements across the wider economy and higher than the consumer price index (CPI) inflation rate, plus an additional 3.3% to 3.5%.