Leadership Focus journalist Nic Paton speaks to school leaders about their experiences of returning to work post-lockdown.

“We had our first positive test on Monday in the year five class, two days into term.” For Tom Shrimpling, assistant head at Brooklands Primary School in Cheshire, the baptism of fire that was the start of the school year made all talk of schools navigating a post-pandemic ‘new normal’ this autumn feel anything but ordinary.

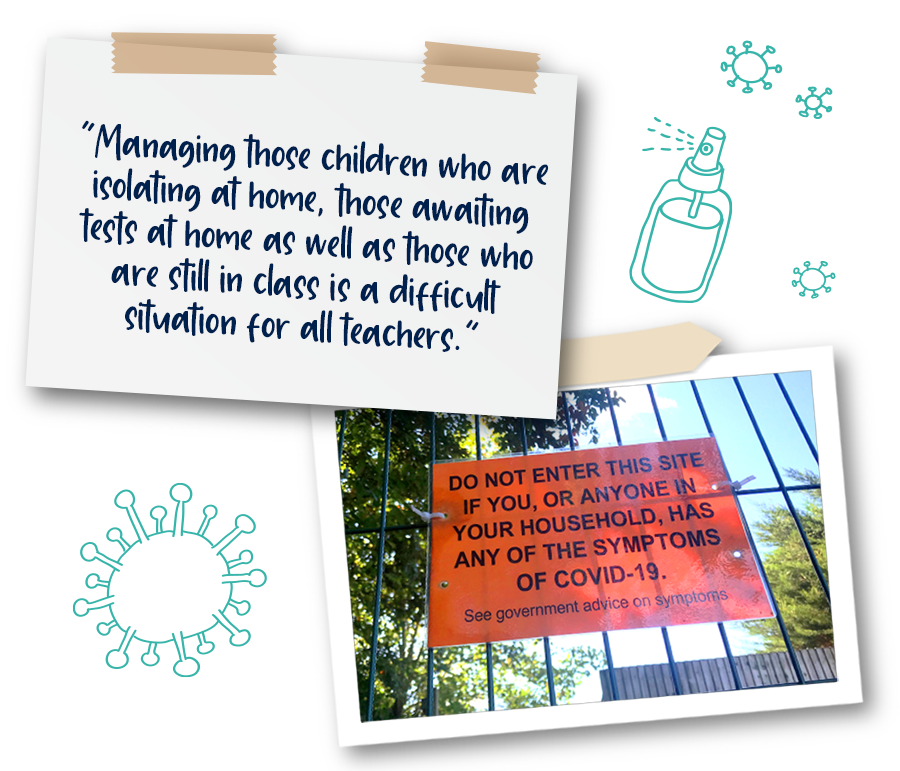

Moreover – with covid-19 cases accelerating fast across the UK during September, classes, ‘bubbles’, teachers and families having to isolate and even whole schools being forced to close within days of reopening – Tom’s experience, sadly, was not unusual. Leadership Focus spoke to Tom and other NAHT members about their initial experiences as schools came back in early September, and you can read their stories later in this article.

Of course, by this time in November, what is a fast-moving situation may already look very different from how it was even just a few weeks ago. Nevertheless, some common themes did emerge, which, in all likelihood, will remain relevant during the months ahead and potentially for this whole school year.

First, the children are great – resilient, adaptable and, by and large, keen to return to schooling and their friends (possibly even to their teachers) after being away for nigh-on seven months, even if a big catch-up job remains in terms of behaviour, learning and attainment.

Second, just as they did in March when the UK was plunged into lockdown (and as Leadership Focus highlighted over the summer), senior leadership, teaching staff and support teams have all risen to the myriad and complex return-to-school challenges with creativity and dedication.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

As NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman emphasises: “These are extraordinary times, and schools have done incredible things in how they’ve responded. Despite the narrative that has played out in some of the ill-informed media over the last few months, school leaders and teachers have been remarkable. They redesigned education to get all pupils back in from the start of September.

“Our message, therefore, is ‘you’ve done amazing things’. There has been no guide for this. We have all had to make this up as we go along. Every school has interpreted the systems of control they need to put in place according to their circumstances, and they have had to be creative. And that is just incredible.”

Yet, alongside this, there are real fears about whether the intensity of the post-pandemic school day is sustainable, especially for senior leaders and given that many head teachers also worked through most, if not all, of the summer. The risks of burnout and heads leaving the profession as a result of these unprecedented times and pressures that schools face are genuine concerns, agrees Paul.

“Members are tired, absolutely,” he says. “This narrative that ‘lazy’ teachers have been off for five months, firstly, just isn’t true. We have members who have not had a proper break since February. What break they would have had over the summer was short-lived rather than a proper recharge because they were preparing their schools for the return. With the government’s advice coming out so late and changing all the time, it meant they were working throughout the summer period. It was relentless.”

Third, with the government’s ‘test and trace’ system struggling, there are growing worries about how schools will maintain bubbles and staffing levels, especially if staff or families have to isolate at home because they cannot get tested. Equally, with restrictions intensifying and local lockdowns looming (if not, at least in September, the prospect of a return to a wholesale national lockdown), there are deep concerns about what a stop-start school year will mean for learning and attainment, especially for our most deprived and vulnerable children. And, looking forward, how in that context it will be remotely possible to have an equitable exam season come the summer.

Finally, and linked to the worries of attainment and progress, there is the whole question of the role and remit of Ofsted during these unprecedented times. Ofsted’s announcement in September that it intended to restart school inspections from the beginning of the new school year, ostensibly merely “to find out how they are managing the return to school” but also sending a letter home to parents, has caused significant disquiet among the profession.

“The inspectorate’s avowed intention of coming into schools to have a professional conversation to capture learnings and good practice and disseminate that across the system is one that we would support,” says Paul.

“But you’re not going to do that if you’re then publishing your view, or the inspectorate’s partial or one-sided view, of what has happened to that school.

“There is a very positive role that Ofsted can play – if it chooses to do so. And I don’t understand why it is not making that choice,” he adds.

LAURA DOEL, NAHT CYMRU DIRECTOR

The situation is also fluid in Wales, as NAHT Cymru director Laura Doel points out. “Wales has been fortunate, in that Estyn promised no inspections this academic year due to the roll-out of the new curriculum,” she explains.

“However, the Welsh Government has now commissioned Estyn to carry out a thematic report into how the local authorities and regional consortia are supporting schools during the pandemic. Despite the initial reassurance that this would not place additional pressure on schools, we have already seen that Estyn wants to meet school leaders and the senior leadership teams to discuss schools’ activities during the pandemic.

“The fact Estyn is not willing to give school leaders a list of the things it wants to discuss before a meeting is also making people more anxious. If this is genuinely about looking at support gaps, why is Estyn unwilling to share the questions beforehand, and why does it also want to survey school staff, parents and governors?

“It is unacceptable for the regulator to expect school leaders in effect to bite the hands that feed them in terms of highlighting the lack of support they are receiving from the local authorities and regional consortia. That creates an ‘us and them’ culture that we are trying to steer away from. We want to work in a more collaborative way to best support schools, their staff and their learners. We will continue to challenge the role and remit of Estyn during this time to ensure it fulfils its promise of an inspection-free year,” Laura adds.

HELENA MACORMAC, NAHT(NI) DIRECTOR

For Northern Ireland, much as in England, members have had to manage as best they can with patchy, vague and often last-minute guidance, emphasises Helena Macormac, NAHT(NI) director.

“For example, we received the school restart document late in August, with no union involvement or consultation, and we had just four hours to review 75 pages. What came out wasn’t consulted on, and it was very contradictory. Multiple times it said ‘where possible’, so head teachers are, a lot of the time, left to make their own decisions,” she says.

“There is a huge disparity between the advice around health, education and public health here, which we are trying to deal with. We’re getting a lot of calls from members in terms of burnout and stress,” Helena adds.

NICK BROOK, NAHT DEPUTY GENERAL SECRETARY

Ultimately, as NAHT deputy general secretary Nick Brook emphasises, however much we may wish it were not the case, the times we’re in are most definitely not ‘normal’. It is, therefore, vital school leaders cut themselves a bit of slack and accept they can only do what they can do.

“We had our first positive test on Monday in the year five class, two days into term.” For Tom Shrimpling, assistant head at Brooklands Primary School in Cheshire, the baptism of fire that was the start of the school year made all talk of schools navigating a post-pandemic ‘new normal’ this autumn feel anything but ordinary.

Moreover – with covid-19 cases accelerating fast across the UK during September, classes, ‘bubbles’, teachers and families having to isolate and even whole schools being forced to close within days of reopening – Tom’s experience, sadly, was not unusual. Leadership Focus spoke to Tom and other NAHT members about their initial experiences as schools came back in early September, and you can read their stories later in this article.

Of course, by this time in November, what is a fast-moving situation may already look very different from how it was even just a few weeks ago. Nevertheless, some common themes did emerge, which, in all likelihood, will remain relevant during the months ahead and potentially for this whole school year.

First, the children are great – resilient, adaptable and, by and large, keen to return to schooling and their friends (possibly even to their teachers) after being away for nigh-on seven months, even if a big catch-up job remains in terms of behaviour, learning and attainment.

Second, just as they did in March when the UK was plunged into lockdown (and as Leadership Focus highlighted over the summer), senior leadership, teaching staff and support teams have all risen to the myriad and complex return-to-school challenges with creativity and dedication.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

As NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman emphasises: “These are extraordinary times, and schools have done incredible things in how they’ve responded. Despite the narrative that has played out in some of the ill-informed media over the last few months, school leaders and teachers have been remarkable. They redesigned education to get all pupils back in from the start of September.

“Our message, therefore, is ‘you’ve done amazing things’. There has been no guide for this. We have all had to make this up as we go along. Every school has interpreted the systems of control they need to put in place according to their circumstances, and they have had to be creative. And that is just incredible.”

Yet, alongside this, there are real fears about whether the intensity of the post-pandemic school day is sustainable, especially for senior leaders and given that many head teachers also worked through most, if not all, of the summer. The risks of burnout and heads leaving the profession as a result of these unprecedented times and pressures that schools face are genuine concerns, agrees Paul.

“Members are tired, absolutely,” he says. “This narrative that ‘lazy’ teachers have been off for five months, firstly, just isn’t true. We have members who have not had a proper break since February. What break they would have had over the summer was short-lived rather than a proper recharge because they were preparing their schools for the return. With the government’s advice coming out so late and changing all the time, it meant they were working throughout the summer period. It was relentless.”

Third, with the government’s ‘test and trace’ system struggling, there are growing worries about how schools will maintain bubbles and staffing levels, especially if staff or families have to isolate at home because they cannot get tested. Equally, with restrictions intensifying and local lockdowns looming (if not, at least in September, the prospect of a return to a wholesale national lockdown), there are deep concerns about what a stop-start school year will mean for learning and attainment, especially for our most deprived and vulnerable children. And, looking forward, how in that context it will be remotely possible to have an equitable exam season come the summer.

Finally, and linked to the worries of attainment and progress, there is the whole question of the role and remit of Ofsted during these unprecedented times. Ofsted’s announcement in September that it intended to restart school inspections from the beginning of the new school year, ostensibly merely “to find out how they are managing the return to school” but also sending a letter home to parents, has caused significant disquiet among the profession.

“The inspectorate’s avowed intention of coming into schools to have a professional conversation to capture learnings and good practice and disseminate that across the system is one that we would support,” says Paul.

“But you’re not going to do that if you’re then publishing your view, or the inspectorate’s partial or one-sided view, of what has happened to that school.

“There is a very positive role that Ofsted can play – if it chooses to do so. And I don’t understand why it is not making that choice,” he adds.

LAURA DOEL, NAHT CYMRU DIRECTOR

The situation is also fluid in Wales, as NAHT Cymru director Laura Doel points out. “Wales has been fortunate, in that Estyn promised no inspections this academic year due to the roll-out of the new curriculum,” she explains.

“However, the Welsh Government has now commissioned Estyn to carry out a thematic report into how the local authorities and regional consortia are supporting schools during the pandemic. Despite the initial reassurance that this would not place additional pressure on schools, we have already seen that Estyn wants to meet school leaders and the senior leadership teams to discuss schools’ activities during the pandemic.

“The fact Estyn is not willing to give school leaders a list of the things it wants to discuss before a meeting is also making people more anxious. If this is genuinely about looking at support gaps, why is Estyn unwilling to share the questions beforehand, and why does it also want to survey school staff, parents and governors?

“It is unacceptable for the regulator to expect school leaders in effect to bite the hands that feed them in terms of highlighting the lack of support they are receiving from the local authorities and regional consortia. That creates an ‘us and them’ culture that we are trying to steer away from. We want to work in a more collaborative way to best support schools, their staff and their learners. We will continue to challenge the role and remit of Estyn during this time to ensure it fulfils its promise of an inspection-free year,” Laura adds.

HELENA MACORMAC, NAHT(NI) DIRECTOR

For Northern Ireland, much as in England, members have had to manage as best they can with patchy, vague and often last-minute guidance, emphasises Helena Macormac, NAHT(NI) director.

“For example, we received the school restart document late in August, with no union involvement or consultation, and we had just four hours to review 75 pages. What came out wasn’t consulted on, and it was very contradictory. Multiple times it said ‘where possible’, so head teachers are, a lot of the time, left to make their own decisions,” she says.

“There is a huge disparity between the advice around health, education and public health here, which we are trying to deal with. We’re getting a lot of calls from members in terms of burnout and stress,” Helena adds.

NICK BROOK, NAHT DEPUTY GENERAL SECRETARY

Ultimately, as NAHT deputy general secretary Nick Brook emphasises, however much we may wish it were not the case, the times we’re in are most definitely not ‘normal’. It is, therefore, vital school leaders cut themselves a bit of slack and accept they can only do what they can do.

“This autumn term is probably going to be one of the most challenging any of us have ever experienced in our entire careers, I suspect.

“And yet, school leaders are doing it; the proof is there in the fact that schools successfully opened from September – so credit to you. We at NAHT want to be, and will be, there to support you in whatever decisions you have to make,” he adds.

SARAH LEE IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF HOGARTH ACADEMY PRIMARY SCHOOL IN NOTTINGHAM, WHICH HAS 210 CHILDREN ON ITS ROLL.

“It has been manic, but in a good way. We were very well supported by our trust (L.E.A.D) at the end of June/July to get ready and prepare in terms of developing our recovery plan for what we would do for the first few days the children were in, and then moving forward. Our risk assessments were all done and approved too. So, when it came to the children coming through the door, it was very much ‘well, we have all the structures and systems ready; we just need the children now’.

“The children have come back in fantastically; they have been fabulous. They enjoy being back in school. When you talk to them, they are just happy to be back with their friends and in a routine. Our children have been remarkably resilient and confident about coming back into school, and they are even enjoying the staggered breaks and lunchtimes. We have everybody back. No one has chosen to home-educate, which was a concern given parental anxieties, and attendance I know will be a concern for colleagues moving forward. I’m sure the national average for attendance will drop this year.

“We’ve had the first few days of a recovery-style curriculum based heavily on personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) work; we’ve then assessed our children to see where our starting points are. Lo and behold, we are very much working at spring/summer one. For example, our year three pupils are really at summer year two level. We are providing a year three diet for them; they need those learning objectives, so we do a pre-assessment as to where they are, and then slowly filter the year two learning objectives out and build in the year three learning objectives over the week. Children are responding well to this.

“There have been high levels of anxiety among staff, particularly in those first few days, about making sure they could keep their distance. And then we had the changing guidance around facemasks and shields, even though that was for secondary schools. We decided to get ahead of the game and ordered our own face shields for staff. We have said to staff they are welcome to wear face shields or facemasks within the class if they wish. Our staffroom is a little small, and so some staff do wear a face shield when in there to make sure they can keep their distance.

“We’ve had staff who have gone for tests, and we have managed to cover that from within, though I know it is becoming a bigger ongoing issue. Thankfully, all tests were negative, and so the staff are now back in the school. As leaders, we must ensure we are making staff feel comfortable, protected and safe, and so we have been reviewing our risk assessment every week at the staff meeting.

“As professionals, we’re juggling and spinning so many plates on a normal week, and then you add the covid-19 plate and people’s anxiety into the mix. It’s a tiring and challenging time. As leaders, we are there with our ‘face’ on saying ‘it’s fine, stick to the risk assessment, do what we need to do to support ourselves and our children, and talk to me if you’re concerned’. And then you turn around, and a child sneezes or coughs on you!

“We’re good at logistics, systems and structures. But that little plate keeps spinning about covid-19 and testing and ‘how is everybody?’

“Then add in catch-up plans. This will cause burnout for some head teachers if they don’t take time for themselves too. I’m sure I’m not the first, nor will I be the last head teacher who has looked at their pension and asked themselves ‘hmm, can I retire yet?’.“I love my job, and I’m not ready to retire yet, but we have to acknowledge it’s challenging at the best of times. We are all in the same boat and need to support each other as leaders.

“Staff members are giving 100%, absolutely, and as the leader, you need to recognise that and be seen to acknowledge that. Looking around the room at a staff meeting, in the hall, when it is socially distanced, and thinking ‘you know what, you all look shattered – let’s get done what’s needed and then get home’.

“Yes, the children were tired at the start, but we are already beginning to see the green shoots. Looking in the books of year six pupils, in terms of productivity, they’re beginning to get through what they would normally get through in a 45-minute maths lesson. But if we then have a lockdown, we’ll lose that. As much as our teachers are highly committed and will ring families every day to check-in, there won’t be that relationship they have within the classroom and with their class teacher to apply themselves and work. The challenge would be keeping that pace and rigour through the lockdown for those children, particularly year six. Because we are still going to be held accountable for their progress and attainment: that’s our job! Pandemic or no pandemic.”

JANIS FRENCH IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF PRIORY WOODS SCHOOL IN MIDDLESBROUGH, A SPECIAL SCHOOL WITH 192 STUDENTS ON ITS ROLL.

“It has been frantic, absolutely frantic, but the children have been amazing; we’ve had very, very few cases of anxiety. They’ve just been desperate to get back, and they’ve been so thrilled to see each other after the best part of six months.

“Our ambition, obviously, is to stay open for the children. At the same time, we want to keep everyone safe. I think what may happen if we see cases spiralling, is that parental anxiety will go through the roof, and they might not send them in. It would also worry me, as it happened during lockdown, that children might physically suffer because they’re not getting access to the resources or therapies they would have in school. The risk is it will be very bitty if they’re in and out. This really won’t be great for their learning.

“I do think there is a real risk of burnout. The summer wasn’t a holiday this year, absolutely it wasn’t. We were open all through Easter and May half-term. I took the two bank holidays over Easter off, but apart from that, February half-term was the last time I had a holiday before the end of the school year. Over the summer, I made a point of putting an out-of-office on my emails, and I didn’t look at emails for a fortnight. After that, I looked after my grandchildren for a couple of days some weeks, but every other day was work.

“I’ve cried already, and I know it has been the same for other colleagues. What we’re doing is dealing with all the covid-19 stuff, but the usual day job hasn’t gone. My school’s development plan feels like it is on the back of an envelope; it is not complete, whereas normally that would be absolutely in place and ready to share with the governors at the start of term. This week, I said I was going to close my door and finish it – but I just have not had the time because of all the other things I have been asked to do.

“But our provision is different, and there are some limitations to our curriculum. This doesn’t mean we are not ambitious. I’d like to see the government recognise this. We have to accept this and that the outcomes at the end of the year may well also be different.”

TOM SHRIMPLING IS THE ASSISTANT HEAD TEACHER AT BROOKLANDS PRIMARY SCHOOL IN SALE, CHESHIRE, WHICH HAS 720 PUPILS ON ITS ROLL.

“One complication for us is that we are head teacher-less at the minute – our head teacher left in March for another job, which he got before the covid-19 crisis. In April, we got a new deputy head who is now our acting head. So, it has been quite a difficult time for her! It also means the four assistant heads have been given additional time out of class to put policies together.

“The children are coping fantastically well; it feels like they’ve never been away. Our kids have come back very enthusiastic for school and to see all their friends. There was some apprehension around covid-19. We can see in some of the pupils the impact of the time off in terms of emotional well-being. We have noticed a few things like sloppiness around handwriting, but generally, the kids have settled back in well. Personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) and well-being are very much at the heart of what we’re doing at the moment as part of our recovery curriculum.

“We had our first positive test on Monday in the year five class, two days into term. So, we sent the whole of year five home. I feel sorry for the year five team. One was a new teacher, so she had only been in the school for two days when suddenly we sent the pupils home.

“We had been planning, as the government asked, to have our home-learning policy up and running by the end of September. At the time when we sent the year five home, it was still a work in progress. So, that is something we’ve had to pull together very quickly over the last couple of days.

“We’ve had some difficult emails and conversations with year five parents who, obviously, weren’t expecting it two days after their children had just returned. It is about us providing the best home-learning environment that we can, but it is also about managing expectations from parents who, naturally, want their children at school. An important part of this is that we have worked alongside parents, received feedback from them and adapted our home-learning practices accordingly.

“We are now reviewing our bubble system as we speak – perhaps going from year bubbles back to singular class bubbles.

“But with a school as large as ours, trying to organise lunchtimes and break times with individual classes – and there are 21 classes across the school – is very difficult. We do appreciate that we had one covid-19 case in year five and it knocked 90 children out of the school.“Lots of us did not expect to be in this situation on day three! So, we’re now working towards a model where that only affects 30 children, not 90 – one that is more based around class bubbles. We’re finding this is working more successfully, and we will hopefully limit the number of children going home when a positive case occurs. But it is an ever-changing process.

“Potentially, there is a danger of burnout; things getting tougher and tougher in terms of the workload. If more bubbles start to go down, how is that going to look? The goalposts in terms of what is expected of us, what is expected from the home learning and the rhetoric in the government’s guidance are difficult things to manage.

“On top of that, managing those children who are isolating at home, those awaiting tests at home as well as those who are still in class is a difficult situation for all teachers. The expectation is that, whether the children are in or out of school, their education is the same. This is a very difficult balance to find when you’re teaching full time yet also attending to the needs of individual/groups of children who are self-isolating away from the class.

“In the current climate and with the parental engagement we have to deal with daily, if Ofsted were to turn up in the next couple of weeks, I don’t see how it would be helpful. I think schools need to be allowed to find their way. It’s a process of constant review; things are moving, things are changing, and schools are doing their best. I don’t see how Ofsted plays a role in what is currently happening.

“How NAHT has been challenging the government and Ofsted is really helpful for members. It is nice for us as members and senior leadership to feel there is a strong voice challenging some of the misconceptions. And for me, it is quite important that, as much as possible, the unions as a whole are relatively on the same page. The one thing this government would love to do is divide us as unions and create divisions.

“Ultimately, it is ‘how can we ensure we have the most children at school at any one time?’. If that’s your thought process as a senior leadership team, then everything else is just logistics. If we work towards the goal of trying to keep as many children in the school as possible and following the correct guidelines as outlined by Public Health England and the government, then I think that has to be a common goal.”

TOM SHRIMPLING IS THE ASSISTANT HEAD TEACHER AT BROOKLANDS PRIMARY SCHOOL IN SALE, CHESHIRE, WHICH HAS 720 PUPILS ON ITS ROLL.

“One complication for us is that we are head teacher-less at the minute – our head teacher left in March for another job, which he got before the covid-19 crisis. In April, we got a new deputy head who is now our acting head. So, it has been quite a difficult time for her! It also means the four assistant heads have been given additional time out of class to put policies together.

“The children are coping fantastically well; it feels like they’ve never been away. Our kids have come back very enthusiastic for school and to see all their friends. There was some apprehension around covid-19. We can see in some of the pupils the impact of the time off in terms of emotional well-being. We have noticed a few things like sloppiness around handwriting, but generally, the kids have settled back in well. Personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) and well-being are very much at the heart of what we’re doing at the moment as part of our recovery curriculum.

“We had our first positive test on Monday in the year five class, two days into term. So, we sent the whole of year five home. I feel sorry for the year five team. One was a new teacher, so she had only been in the school for two days when suddenly we sent the pupils home.

“We had been planning, as the government asked, to have our home-learning policy up and running by the end of September. At the time when we sent the year five home, it was still a work in progress. So, that is something we’ve had to pull together very quickly over the last couple of days.

“We’ve had some difficult emails and conversations with year five parents who, obviously, weren’t expecting it two days after their children had just returned. It is about us providing the best home-learning environment that we can, but it is also about managing expectations from parents who, naturally, want their children at school. An important part of this is that we have worked alongside parents, received feedback from them and adapted our home-learning practices accordingly.

"We are now reviewing our bubble system as we speak – perhaps going from year bubbles back to singular class bubbles.

"But with a school as large as ours, trying to organise lunchtimes and break times with individual classes – and there are 21 classes across the school – is very difficult. We do appreciate that we had one covid-19 case in year five and it knocked 90 children out of the school.“Lots of us did not expect to be in this situation on day three! So, we’re now working towards a model where that only affects 30 children, not 90 – one that is more based around class bubbles. We’re finding this is working more successfully, and we will hopefully limit the number of children going home when a positive case occurs. But it is an ever-changing process.

“Potentially, there is a danger of burnout; things getting tougher and tougher in terms of the workload. If more bubbles start to go down, how is that going to look? The goalposts in terms of what is expected of us, what is expected from the home learning and the rhetoric in the government’s guidance are difficult things to manage.

“On top of that, managing those children who are isolating at home, those awaiting tests at home as well as those who are still in class is a difficult situation for all teachers. The expectation is that, whether the children are in or out of school, their education is the same. This is a very difficult balance to find when you’re teaching full time yet also attending to the needs of individual/groups of children who are self-isolating away from the class.

“In the current climate and with the parental engagement we have to deal with daily, if Ofsted were to turn up in the next couple of weeks, I don’t see how it would be helpful. I think schools need to be allowed to find their way. It’s a process of constant review; things are moving, things are changing, and schools are doing their best. I don’t see how Ofsted plays a role in what is currently happening.

“How NAHT has been challenging the government and Ofsted is really helpful for members. It is nice for us as members and senior leadership to feel there is a strong voice challenging some of the misconceptions. And for me, it is quite important that, as much as possible, the unions as a whole are relatively on the same page. The one thing this government would love to do is divide us as unions and create divisions.

“Ultimately, it is ‘how can we ensure we have the most children at school at any one time?’. If that’s your thought process as a senior leadership team, then everything else is just logistics. If we work towards the goal of trying to keep as many children in the school as possible and following the correct guidelines as outlined by Public Health England and the government, then I think that has to be a common goal.”

ANTONY LOWE IS THE PHASE COORDINATOR AND CURRICULUM LEAD AT AN INNER-CITY PRIMARY SCHOOL IN BIRMINGHAM, WHICH HAS 442 PUPILS ON ITS ROLL.

“We have managed to get most of the children back, and they have been really, really positive. Our experience is that the children are adapting to the measures we are putting in place overall very well.

“Where the children are in terms of readiness to learn has been quite challenging. What I’ve found is routines and sustaining their learning over time, over a whole day, has been difficult for some pupils. Despite all we did over lockdown and the work many of our parents did with their children, some children might not have picked up a pencil or engaged in much school-set learning over that period. The regression with basic skills has been quite noticeable.

“If I’m honest, I think we’re already exhausted. Naturally, as a teacher, you think ‘right, it’s the September term’, and you have your aspirations of what that looks like. You inherit a year group that has had six weeks off, and you expect them to be in a certain place. This year, I am finding it quite daunting in terms of the amount of learning that has not necessarily been lost but forgotten. It needs to be over-learnt and rekindled.

“I have had many conversations with staff who have been saying ‘I’m trying to do this, and the children are just not ready’. There is naturally a level of staff members’ anxiety, but we have done what I think all teachers do – just roll up our sleeves and get on with it. We tend to put aside our worries and fears, and we just get on with it for the benefit of the children.

“I think the next few weeks and months are really going to be quite tricky. One of the things we have to do is think about those lockdown scenarios. If we had a local lockdown and that affected the school, we do have procedures in place, and quite a lot of our parents accessed work online during lockdown. But, equally, we had families that found online learning difficult to access. We are trying to work through the lessons learnt from lockdown and how we can improve the provision, particularly for those who are digitally excluded. But there is no easy fix for this.

“We all know learning happens when you have consistency over time; children like routines, and we can build on that. But if we have chop and change and if children are in and out of school, that will impact their learning significantly.

“We always have SATs early in the second week of May, when you still have seven or eight weeks of the term left. SATs determine nothing other than school data. So, if they must go ahead, push them back.

“The government should listen carefully to what we as a profession are finding. Maybe primary school teacher assessment is the way forward for this year rather than SATs? What I would most like to see is the government engaging with the profession; talking to us and listening to what we have to say about exams and assessment.

“The thought of Ofsted coming in this term is not helpful. We don’t need Ofsted to tell us what we should be doing. As professionals, we know what we need to do. It is just added pressure that we don’t need at this time.

“Throughout this, I think the messages that have come out from NAHT have been excellent. It has spoken clearly and challenged the government, but in a constructive way, which I think is important. I want to see NAHT continue to engage with the government – being that voice that brings lived experiences to the table. So, I hope NAHT keeps doing what it has been and can shape education policy in these difficult times.”

SUSAN CAMPBELL IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF THE LOYNE SPECIALIST SCHOOL IN LANCASTER, WHICH HAS 117 STUDENTS ON ITS ROLL.

“On the whole, young people have returned really well. We did think there might be some additional or new behaviours that we would need to support or there would be some trauma or mental health issues that had not been picked up through liaison with the family. But, overall, the return to full opening has gone very smoothly.

“One of the unforeseen consequences of the government’s guidance was the length of time it would take if any staff members or pupils required a covid-19 test. What we’re dealing with now, therefore, is staff members’ absences while they wait for a test. With the results taking up to five days to come back, we can struggle to cover their absence because of the bubble model. Staff feel terrible being at home and offer support, but there is only so much they can do remotely as the need is within the classroom!

“Because we’re in small class bubbles with no movement of staff between, this has a knock-on effect. We decided against having large social bubbles because that would necessitate several classes and staff self-isolating if we had a positive case. We opted for a class-based model, which reduces the number of pupils absent, but it could increase the frequency in which they are absent due to our inability to provide cover across school without breaking bubbles. So, I have spent three hours just this morning with my senior leadership team looking at what would be an intolerable level of staff members’ absence within each bubble and would cause it to collapse.

“If we do have to collapse bubbles or have school closures, the priority is going to be more around how we keep the children purposefully engaged in meaningful activities that address their education, health and care (EHC) plan outcomes while they are at home.

“The majority of our young people are not independent learners. So, for us, when we are looking at our blended learning, the questions are ‘how do we support our parents to work with their child at home effectively?’, ‘what would that look like?’ and ‘how can we bring those learning moments at school into the home?’. And, within that, ‘how can we give parents the reassurance that what they are doing is good?’. Some parents are very wary of their skills and do not feel very effective. But it is also getting that message across that they’re doing a good job.

“Leaders work hard to create strong ethos-driven teams. As a leader, I am confident, given all we are dealing with, that we can continue to provide an excellent holistic education for our young people. My governors have also provided me with a robust challenge and demonstrated an understanding of the complexities my senior leadership team is dealing with. This level of understanding has kept us sane.

“But, in such uncertain times, it is essential the message promoted by Ofsted is also one of ‘a critical friend’ – one that listens and supports without judgement. Misunderstanding the needs and dilemmas of the profession at such a critical time will lead to transactional operations, risking the very foundations on which we all build our schools.

“We are having to make decisions daily as to the safety of pupils and staff, contingency plans and mitigating risk.

“NAHT is supporting us in that really nuanced decision-making.“The media does not reflect the complexity of what schools are dealing with on a daily basis. NAHT, by comparison, is fabulous at synthesising the thoughts and concerns of its members. However, there is still much to be done to tackle the wider misrepresentations of schools and school leaders in the media, be that online or in print.”

SUSAN CAMPBELL IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF THE LOYNE SPECIALIST SCHOOL IN LANCASTER, WHICH HAS 117 STUDENTS ON ITS ROLL.

“On the whole, young people have returned really well. We did think there might be some additional or new behaviours that we would need to support or there would be some trauma or mental health issues that had not been picked up through liaison with the family. But, overall, the return to full opening has gone very smoothly.

“One of the unforeseen consequences of the government’s guidance was the length of time it would take if any staff members or pupils required a covid-19 test. What we’re dealing with now, therefore, is staff members’ absences while they wait for a test. With the results taking up to five days to come back, we can struggle to cover their absence because of the bubble model. Staff feel terrible being at home and offer support, but there is only so much they can do remotely as the need is within the classroom!

“Because we’re in small class bubbles with no movement of staff between, this has a knock-on effect. We decided against having large social bubbles because that would necessitate several classes and staff self-isolating if we had a positive case. We opted for a class-based model, which reduces the number of pupils absent, but it could increase the frequency in which they are absent due to our inability to provide cover across school without breaking bubbles. So, I have spent three hours just this morning with my senior leadership team looking at what would be an intolerable level of staff members’ absence within each bubble and would cause it to collapse.

“If we do have to collapse bubbles or have school closures, the priority is going to be more around how we keep the children purposefully engaged in meaningful activities that address their education, health and care (EHC) plan outcomes while they are at home.

“The majority of our young people are not independent learners. So, for us, when we are looking at our blended learning, the questions are ‘how do we support our parents to work with their child at home effectively?’, ‘what would that look like?’ and ‘how can we bring those learning moments at school into the home?’. And, within that, ‘how can we give parents the reassurance that what they are doing is good?’. Some parents are very wary of their skills and do not feel very effective. But it is also getting that message across that they’re doing a good job.

“Leaders work hard to create strong ethos-driven teams. As a leader, I am confident, given all we are dealing with, that we can continue to provide an excellent holistic education for our young people. My governors have also provided me with a robust challenge and demonstrated an understanding of the complexities my senior leadership team is dealing with. This level of understanding has kept us sane.

“But, in such uncertain times, it is essential the message promoted by Ofsted is also one of ‘a critical friend’ – one that listens and supports without judgement. Misunderstanding the needs and dilemmas of the profession at such a critical time will lead to transactional operations, risking the very foundations on which we all build our schools.

“We are having to make decisions daily as to the safety of pupils and staff, contingency plans and mitigating risk.

“NAHT is supporting us in that really nuanced decision-making.“The media does not reflect the complexity of what schools are dealing with on a daily basis. NAHT, by comparison, is fabulous at synthesising the thoughts and concerns of its members. However, there is still much to be done to tackle the wider misrepresentations of schools and school leaders in the media, be that online or in print.”

KAREN BOYNTON IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF HIGHCLIFFE ST MARK PRIMARY IN CHRISTCHURCH, DORSET, WHICH HAS 650 CHILDREN ON ITS ROLL.

“We’ve had children back in normally for a week now, and today was our first day back properly including foundation; last week, they were coming in for visits. So, we’ve now got the vast majority of our 650 children in – although we haven’t done pickups yet for foundation children!

“Mostly, it’s gone well. The children have been great. Perhaps 90% to 95% have come back really settled, and they have adjusted quickly.

“I have been warning staff there is a danger that, if we’re not careful, this might be a bit of a honeymoon period.“I don’t want us to assume they’re all fine and then jump into learning. In fact, I think one of the reasons they’re fine is because we haven’t jumped straight into learning; we’ve been taking things very carefully.

“There are lots of new routines, and the staff have been doing positive activities, lots of well-being and getting-to-know-you activities; a lot of reconnection with their class, team-building activities and outdoor learning. What we’ve put in place seems to be working well.

“We had some issues with anxiety among the staff back in June. We decided to bring all the staff back then, bar those who were shielding, because we had a third of the school in. At the time, that was challenging, particularly for those who hadn’t been in at all since March. But the staff have adapted to all the different ways of working brilliantly.

“We’ve used NAHT’s guidance, which has been brilliant, local guidance and just any information we could get, and we stuck to it. I think that gave staff the confidence they could come in safely to school. We were on a rota system, two days on and two days off. We also worked out a maximum number of hours a week they were to work. I think that has helped and kept staff fit, healthy and well. There was also a sense of fairness that everybody was having the same contact time with children and support at home.

“One thing we found very early on was it is much more tiring being in school now than before covid-19. You have to concentrate so much more on ‘oh, when did I last wash my hands?’, ‘oh, I’ve just touched something; I’ve got to go and wash my hands’, or ‘I’ve got to keep my 2m distance’. So, mentally, it is really draining.

“My husband makes me pace myself! My governors are also brilliant – they’ve protected and looked after me, and my senior leadership team (SLT) members have shared the load, too, so it has been a real group effort. During lockdown, while my SLT did the two days on, two days off rota, I took the decision not to. I came in every day, but I went home in between. I would come in for two or three hours to make sure everything was sorted. Then in the evenings, my husband and I did food parcel deliveries. But I still got home at a reasonable time.

“The thing is – say you have a case or something happens – yes, my SLT members are brilliant and I can trust them with decisions, but they would want to run them past me. If I’m not there, that is another thing they’ve got to think about. I’ve tried wherever possible – well, I was made – to have at least one day off at the weekend.

“Now we’re back, I’m going to try and have at least one afternoon every other week working from home. That’s the theory at least! We’re all going home earlier; we have told everybody that no one is to be in school after 5pm, at the very latest. We’re doing small staff meetings or Zoom meetings. And I’m trying to stick to just working one day of the weekend where I can.

“Local lockdowns and closures are going to be disruptive. We’re already experiencing – and I know we’re not the only school – issues with staff, or their families, not being able to get tests. At the moment, I can still staff things, but I can see a point where I may run out of supply cover and cover. If it’s taking a good six days to get a test result back, then it’s going to be tricky.

“My concern is more that we may have lots of children at home who don’t need to be at home, who can’t get tests. It is frustrating if we get to the point where – and at the moment it’s not, but I can see it happening – parents start blaming the schools. We have learning set up for the children, on our websites, and it’s all ready to go. We’re moving to an online learning platform, which the staff have all had training on. Now, we have to share that with parents and how it’s going to work. We’re also hoping to use that for normal homework.

“I think NAHT has been brilliant throughout. I’ve been impressed – the emails from Paul Whiteman have been amazing. I hope he is managing to take a break or two too. He needs to be looked after, as well as him looking after all of us!

“It’s been really supportive, really reassuring. Just in terms of saying to heads ‘you know your school, and you know what you’re doing; keep going and stick to your guns’ – that is powerful because you do self-doubt sometimes. I think the fact NAHT is pushing for the right things from the government is also great.”

KAREN BOYNTON IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF HIGHCLIFFE ST MARK PRIMARY IN CHRISTCHURCH, DORSET, WHICH HAS 650 CHILDREN ON ITS ROLL.

“We’ve had children back in normally for a week now, and today was our first day back properly including foundation; last week, they were coming in for visits. So, we’ve now got the vast majority of our 650 children in – although we haven’t done pickups yet for foundation children!

“Mostly, it’s gone well. The children have been great. Perhaps 90% to 95% have come back really settled, and they have adjusted quickly.

“I have been warning staff there is a danger that, if we’re not careful, this might be a bit of a honeymoon period.“I don’t want us to assume they’re all fine and then jump into learning. In fact, I think one of the reasons they’re fine is because we haven’t jumped straight into learning; we’ve been taking things very carefully.

“There are lots of new routines, and the staff have been doing positive activities, lots of well-being and getting-to-know-you activities; a lot of reconnection with their class, team-building activities and outdoor learning. What we’ve put in place seems to be working well.

“We had some issues with anxiety among the staff back in June. We decided to bring all the staff back then, bar those who were shielding, because we had a third of the school in. At the time, that was challenging, particularly for those who hadn’t been in at all since March. But the staff have adapted to all the different ways of working brilliantly.

“We’ve used NAHT’s guidance, which has been brilliant, local guidance and just any information we could get, and we stuck to it. I think that gave staff the confidence they could come in safely to school. We were on a rota system, two days on and two days off. We also worked out a maximum number of hours a week they were to work. I think that has helped and kept staff fit, healthy and well. There was also a sense of fairness that everybody was having the same contact time with children and support at home.

“One thing we found very early on was it is much more tiring being in school now than before covid-19. You have to concentrate so much more on ‘oh, when did I last wash my hands?’, ‘oh, I’ve just touched something; I’ve got to go and wash my hands’, or ‘I’ve got to keep my 2m distance’. So, mentally, it is really draining.

“My husband makes me pace myself! My governors are also brilliant – they’ve protected and looked after me, and my senior leadership team (SLT) members have shared the load, too, so it has been a real group effort. During lockdown, while my SLT did the two days on, two days off rota, I took the decision not to. I came in every day, but I went home in between. I would come in for two or three hours to make sure everything was sorted. Then in the evenings, my husband and I did food parcel deliveries. But I still got home at a reasonable time.

“The thing is – say you have a case or something happens – yes, my SLT members are brilliant and I can trust them with decisions, but they would want to run them past me. If I’m not there, that is another thing they’ve got to think about. I’ve tried wherever possible – well, I was made – to have at least one day off at the weekend.

“Now we’re back, I’m going to try and have at least one afternoon every other week working from home. That’s the theory at least! We’re all going home earlier; we have told everybody that no one is to be in school after 5pm, at the very latest. We’re doing small staff meetings or Zoom meetings. And I’m trying to stick to just working one day of the weekend where I can.

“Local lockdowns and closures are going to be disruptive. We’re already experiencing – and I know we’re not the only school – issues with staff, or their families, not being able to get tests. At the moment, I can still staff things, but I can see a point where I may run out of supply cover and cover. If it’s taking a good six days to get a test result back, then it’s going to be tricky.

“My concern is more that we may have lots of children at home who don’t need to be at home, who can’t get tests. It is frustrating if we get to the point where – and at the moment it’s not, but I can see it happening – parents start blaming the schools. We have learning set up for the children, on our websites, and it’s all ready to go. We’re moving to an online learning platform, which the staff have all had training on. Now, we have to share that with parents and how it’s going to work. We’re also hoping to use that for normal homework.

“I think NAHT has been brilliant throughout. I’ve been impressed – the emails from Paul Whiteman have been amazing. I hope he is managing to take a break or two too. He needs to be looked after, as well as him looking after all of us!

“It’s been really supportive, really reassuring. Just in terms of saying to heads ‘you know your school, and you know what you’re doing; keep going and stick to your guns’ – that is powerful because you do self-doubt sometimes. I think the fact NAHT is pushing for the right things from the government is also great.”

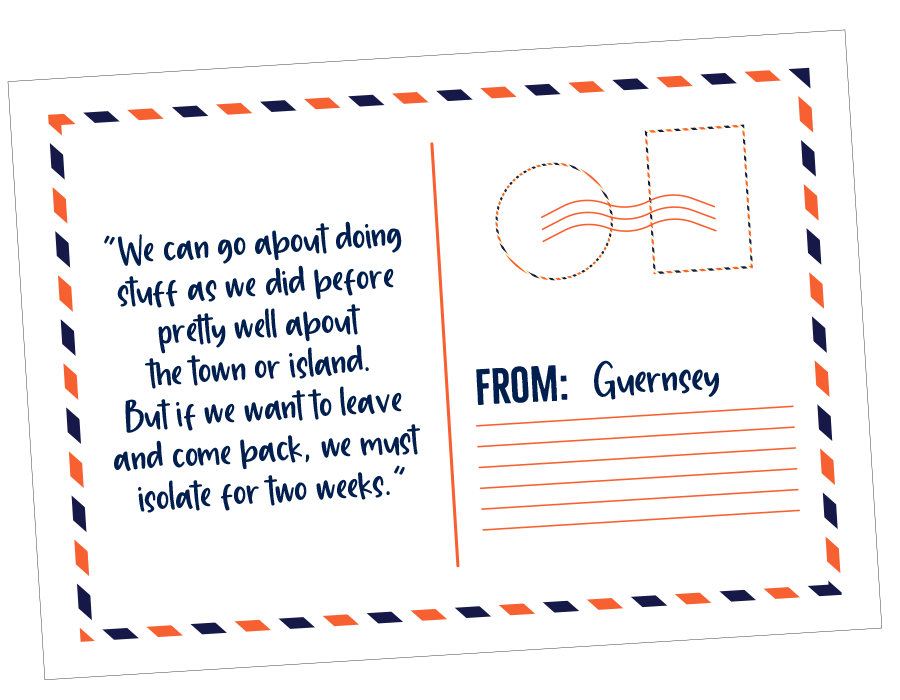

TIM WALTERS IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF VAUVERT PRIMARY SCHOOL IN ST PETER PORT, GUERNSEY, WHICH HAS 340 CHILDREN ON ITS ROLL PLUS SEVEN WHO COME OVER FROM HERM ISLAND.

“Guernsey is slightly different to the UK in that we’ve been pretty much covid-19-free for about 120 days now and so, within that, we’ve been able to move from bubbles initially in June to no bubbles now.

“Life feels fairly back to normal. But it is a bit of a gilded cage. No masks and no social distancing required; we can go about doing stuff as we did before pretty well about the town or island. But if we want to leave and come back, we must isolate for two weeks. So, it is a lovely place to be stuck, but it does mean we can’t go anywhere really.

“We’re still on a heightened level of concern, however. If children do come in and present any symptoms, we need to quarantine them in a sick room, and then they get sent home. And generally, parents have been very supportive of that. So, yes, we’re in a different position to the UK, but we’re still having to be very careful regarding hygiene and cleaning regimes, which have then had an implication on curriculum delivery, timetables and so on.

“We were very conscious of anxiety issues from the beginning. We were conscious children might feel very anxious, particularly when coming back to school; being quite anxious about whether they should go and say hello to their friends or hold hands with their friends. We’ve also seen an increase in anxiety from children related to not being able to see grandparents or relatives in the UK or further afield because of the self-isolation restrictions.

“In terms of staff, there were similar early anxieties about being in the classroom with a large number of children. For example, ‘what happens if one of them has covid-19?’. Equally, staff who might have underlying health issues. So, we did a lot of work early on to identify those who might have health issues, who might also be anxious or worried about being back in the classroom with the children. We did a lot of work to ensure either that we could manage those anxieties for them or, if it was about health issues, rearrange timetables, rotas and systems to allow them to look after themselves.

“We have the routines around bubbles. We have processes in place for if we needed to send home classes or year groups, if we were stuck for staff or if we needed to rearrange the school so it could still function with reduced numbers of staff or pupils. We have prepped for a lot of the various scenarios that may happen; the only issue is we’re never sure whether we will have covered every scenario.

“I do think there is a danger of people working themselves into the ground. We found, last term, when we came back into bubbles in June and then back to almost normal, staff were exhausted.

“Even though we’ve got minimal extra restrictions on us here, staff are really, really tired. So, I have looked to reduce considerably what we might be trying to cover in the year.“My school’s development plan last year didn’t happen, but that’s understandable. What we put into it this term – I don’t write a long plan anyway, and it has about three or four priorities every year – we’ve tailored so that if we do feel it is in any way overloading staff, we can ease back on it without detracting from the work.

“We do a lot of work with the staff on mental health and well-being, and within that, we are limiting things like meetings to a minimum. We’re doing work to limit what our expectations are of the staff so that they can focus on the pupils. It is hard to do that when you’re being pushed and pulled by external agencies, local authorities or the government to work on this area of the curriculum or develop schemes for this, that or the other. I see us, heads, being quite a gatekeeper within all that.

“I think there is also an element within this that we look after everyone else, but who looks after us? Particularly coming back now after having had the bubbles and all the process of the lockdown from March. The effect on head teachers was profound, and I’m not sure we’ve cracked how best to look after our head teachers.

“For myself, and for my SLT as well, I am going to look at the ‘must’, ‘should’ and ‘could’ lists of what we need to do. We are focusing on working on the important things that we should be doing anyway. Teachers are great at saying ‘yes, I’ll do that’ or ‘yes, I’ll help with that’.

“Guernsey just signed up to Ofsted. Up until this year, we used to have inspections from other teams. I’d, however, like to see that transition deferred to allow schools to get back into what they should be doing so that we can focus on supporting the children and dealing with the after-effects of the lockdown – children’s anxiety and well-being and staff members’ mental health and well-being. Unless Ofsted can be supportive and understanding of the school’s context, it could be the thing that tips a lot of schools over the edge.

“NAHT has done a brilliant job of lobbying and working with the government to help our cause. I also think lockdown, for a lot of parents, has made them realise just what job schools do and what brilliant work teachers do, which is an opportunity for the profession.

“So, I’d like to see NAHT continuing that work to lobby governments, officials, agencies and so on, so that they understand the pressures schools are under and look at the ways heads and senior leaders in schools are supported.”

LEANNE TODD IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF ROSEBROOK PRIMARY SCHOOL IN STOCKTON-ON-TEES, WHICH HAS 450 CHILDREN ON ITS ROLL.

“I came across to Rosebrook as head teacher-designate in April to job-share with the previous head teacher, and I have been flying solo now for three weeks. What with coming over in the middle of a pandemic and working on the covid-19 plan and risk assessments ever since – this job is not what I was expecting!

“For the majority of people, the school has felt normal; a happy place. The children have been very happy to come back. Our attendance has been really good – we were at 97% attendance on our first day back. That has dipped somewhat as we have had some pupils with symptoms who have had to self-isolate. And then there are the normal autumn common colds as well.

“We’re remaining quite cautious, following the guidance, of course. That said, if people haven’t got one of the three covid-19 symptoms, then we’re still encouraging parents to send their children to school, even if they’ve got a cold.

“Before we came back in the summer, I was taking a lot of calls from very anxious parents, particularly the week before we came back. We had some parents who were point-blank refusing to send their children back because they said we couldn’t guarantee their safety. I had to talk them through our risk assessments and everything we had in place. On one occasion, I invited a family in to see for themselves the additional safety measures we had implemented.

“The staff have been absolutely brilliant. Now, as the weeks are passing, the likelihood of the closure of a bubble, even full closure or lockdown is quite imminent. A lot of the local schools around us have been affected. So, we are having to prepare our home-learning offer, which is probably what is causing the most stress and anxiety now.

“But we have some who have children and other dependants at home, and their concern, understandably, is how they are going to manage to provide a good education for the pupils at home when they have their own responsibilities. We have to talk through all these scenarios and offer flexible solutions to meet the government’s expectations of a robust home-learning offer.

“As we saw during lockdown, we didn’t have 100% take-up of home learning. So, it is trying to hold parents to account if their children aren’t engaging. But there is also a massive expectation for parents to be able to support their children at home. We have to be very careful with what we say we are going to set for children.

“We have talked about making sure the learning is differentiated so that children can access it at their level; we have talked about the importance of teachers’ explanations and modelling. If they don’t deliver a live lesson, then do one that is pre-recorded with video clips or PowerPoints with voiceovers. Over the next week or two, we will be training the children on how to access their home learning while they are still at school.

“But the other problem, of course, is that not every home has the right technology. Not every home has a laptop or iPad, or even access to the internet. It was very difficult before the summer when we used the website for home learning, but we do now have a learning platform where we can set work and have a facility that children can use to send work back to their teacher to look at and give feedback. We have been busy reimagining the school’s laptops ready to be sent home if a bubble must isolate.

“As well as the pressures of covid-19, there are still the usual school pressures. For example, we’re advertising for a deputy head, which we hope to appoint in the next few weeks. But it does mean me and the assistant head have already felt quite stretched.

“When we put our risk assessments in place, with lots of new and different procedures, we were the ones who wanted to go out on the yard and be around the school to make sure they were working – staggered starts, lunchtimes and so on. So, we are involved in all those times. We’re monitoring the playground, and we’re monitoring movement around the school.

“It does mean the other tasks that you might normally be involved in at this time of the year are just piling up on your desk, while you are – 90% of the time – dealing with issues relating to health and safety, staffing problems, risk assessments and covid-19. So, yes, there is a danger of burnout.

“We’ve just decided to scrub some things out of the diary that were putting extra pressures on us. We’ve said ‘right, what are our top five priorities for the next two weeks?’, and as long as we get those things done and sorted, then the rest of the things can wait. We had staff meetings planned for the term ahead; the focus for them has changed already to home learning and contingency planning. No two days are the same, and even though it’s fast and furious, I’m enjoying every minute.”

RANJNA SHIYANI IS THE HEAD TEACHER OF ASHLEY COLLEGE, A SPECIALIST MEDICAL NEEDS PUPIL REFERRAL UNIT IN BRENT, LONDON, WITH A CAPACITY FOR 20 CHILDREN AT THE CENTRE, HOME TUITION ACROSS THE BOROUGH AS WELL PROVIDING LEARNING TO A FIVE-BED MEDICAL SECURE UNIT.

“I love the job I do. Like for most head teachers, covid-19 meant even more hours of work. Before the pandemic, I would usually be in school until 7pm or 8pm, but on a Friday, I would try to leave at 4.30pm. During the summer term, we delivered well-being, yoga, tutor time, assemblies and staff meetings remotely on a Friday, which enabled teachers to work from home and prepare their online resources.

“But I had several remote meetings each Friday; there was also an immense amount of updates and new information coming to me from the government, local authority, unions, local school clusters, etc.

“Head teachers felt a constant fear that they might drop something. The pressure to safeguard and ensure the health and safety of staff and students – that was very stressful. I was not turning my computer off until after 8pm every Friday.

“Online teaching and learning meant a lot of work initially; our teachers had to learn quickly. Early in the summer term, my team started with a rota of two days a week, and we quickly went to four days a week. We didn’t shut.

“Although we did not have any key worker children, we consider all our children as vulnerable. Initially, students and families’ anxieties were high. But as we continued supporting our community with well-being sessions, phone calls, daily contact, etc., they felt more assured, and engagement with learning improved. Because our numbers are small, we are fortunate, in that we have enough space to distance ourselves and put robust systems in place.

“We’re lucky in the sense that we’re small, so we’ve been able to implement our online curriculum fully to run in line with our centre-based curriculum, and we have added new ways of learning. Now we can do remote learning much more effectively, we’ve put languages on, which we didn’t have the resources to do before. We have sourced teachers from outside of London; they deliver lessons remotely via webcam and set work on Google Classroom, while the student is in our centre with a teaching assistant who supports them.

“So, we’ve expanded our offer, and this week I have got Japanese, French and Portuguese being taught.“If we get into a situation of local lockdowns again, the difficulties we’d have would be around sustaining the work we have done with students and families on resilience and well-being, as the majority of our students are referred to us because of mental health and anxiety. And, also, the worry of the qualifications our students achieve – although we are interim provision, we do aim to get our year 11s as many GCSEs as possible so that they have the pathway to further education or employment. I am hoping they do make exams later next summer.

“I’ve just met with my support staff, some of whom have primary-age children. Because their children’s schools are doing staggered starts, they’re having difficulty dropping off and picking up their children. I have to think about our school day timings; it is complex, but this problem is even bigger for mainstream schools.

“Alongside this, if certain bubbles in primary schools have to shut down and I have staff with children in those bubbles who have to isolate for 14 days, that becomes very hard and complex for me to manage. We do equip our staff who may have to self-isolate so that they can teach and work remotely.

“We have set up procedures where a student having to isolate can join the lessons in the centre via webcam, and we upload all the work onto Google Classroom; this enables continuity of learning, and students still feel part of their group. Where a teacher may have to isolate, they deliver webcam lessons from home while students are supported by teaching assistants in the school. We have strategies, but we are very dependent on the efficiency and availability of broadband and online learning platforms, which makes it all very complex.”