Journalist Nic Paton looks at the recent RAAC crisis and speaks to NAHT members, asking how such a large problem could’ve slipped through the cracks.

By rights, it should be affected head teachers, senior, middle and business leaders, teaching staff and facilities managers who have most reason to be making expletive-laden comments about how well they’ve been coping with the RAAC ‘crumbly concrete’ emergency since the autumn.

CHRIS KIRKHAM-KNOWLES,

NAHT YORKSHIRE NATIONAL EXECUTIVE

COMMITTEE REPRESENTATIVE

They would, of course, all probably be much too professional to do so. Yet, as NAHT Yorkshire National Executive Committee representative Chris Kirkham-Knowles makes clear, the way school teams have come together and responded in adversity to this crisis needs – quite rightly – to be celebrated.

“What I’d like to get across is the amazing job the team is doing in terms of going above and beyond. And within that, I’m very much just a small cog,” he tells Leadership Focus.

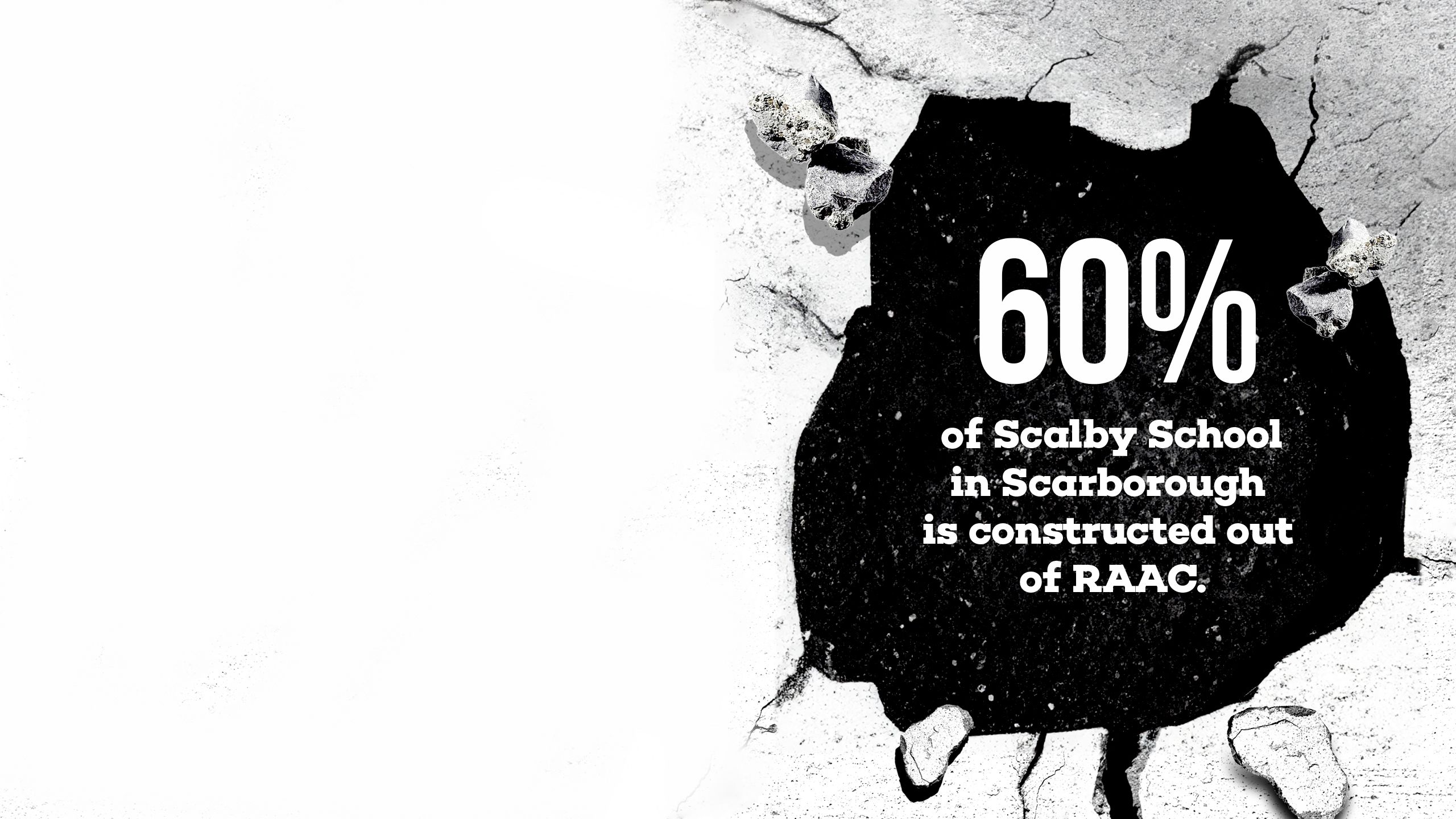

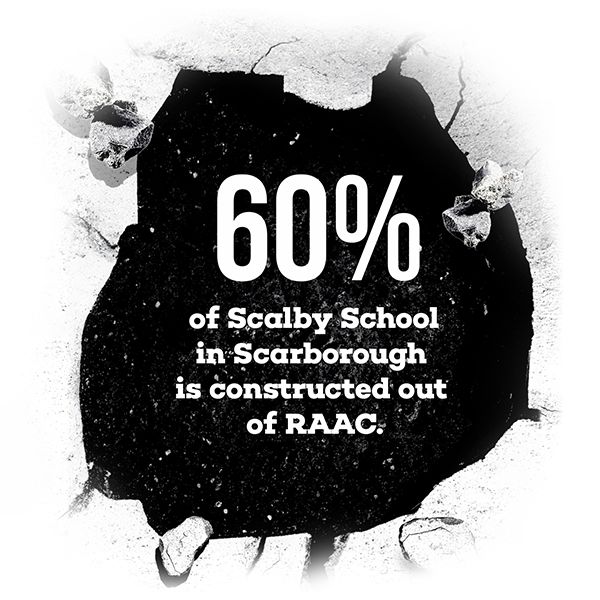

Chris is the primary executive leader at Coast and Vale Academy, a multi-academy trust based in Scarborough that manages seven schools spread across North Yorkshire. One of these, Scalby School, a secondary with 1,000 students also in Scarborough, discovered earlier this year that it was 60% constructed out of RAAC, or ‘reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete’ to give it its full name.

“The school has known since the Department for Education (DfE) started to identify that RAAC surveys were needed. We go right back to January or February when this first all became apparent,” he explains.

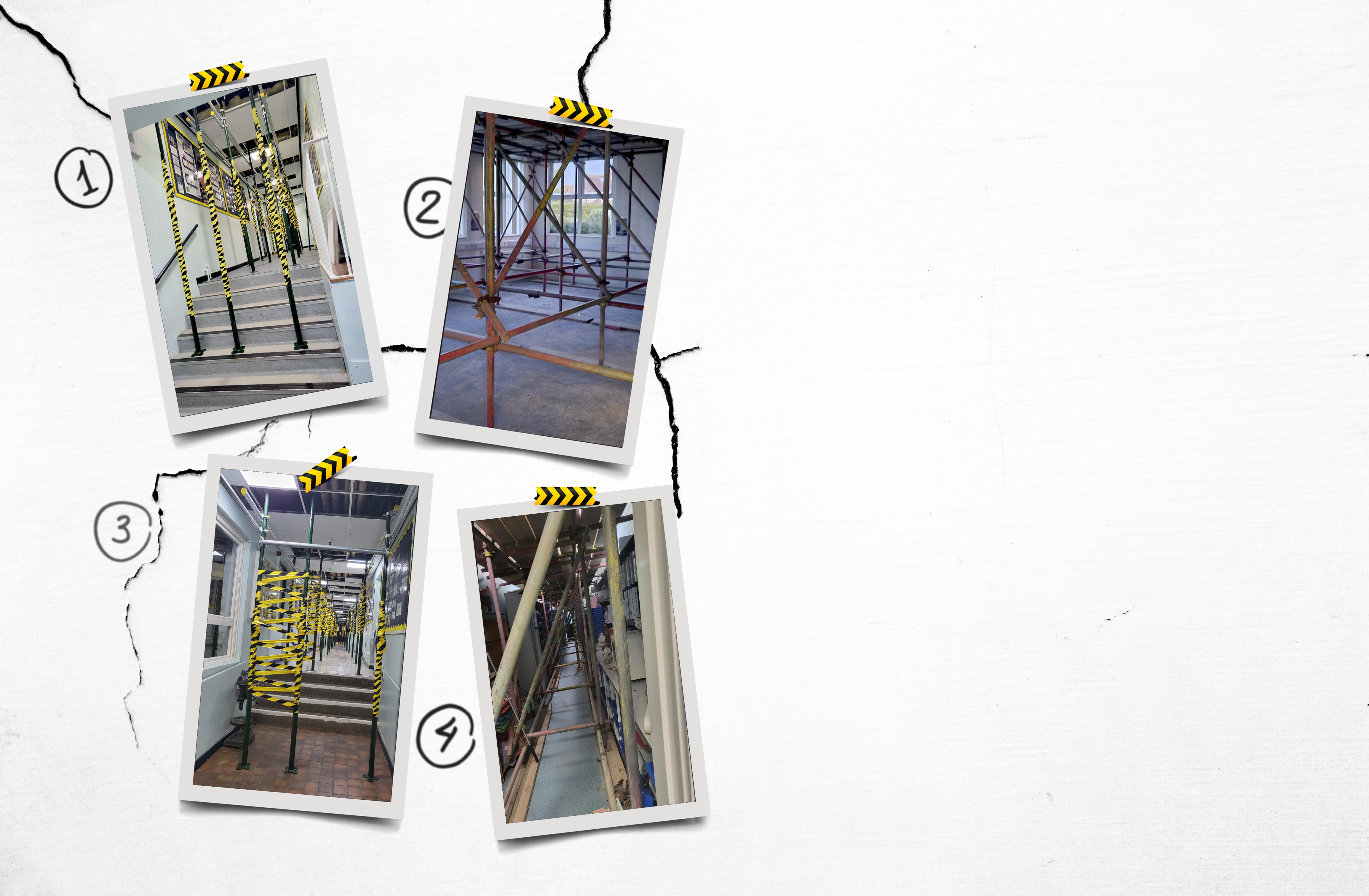

“We were actually already undertaking mitigating works in the school over the summer. Before school broke up, there were already some corridors and rooms with props in them, albeit a small number. But at that point, the school was still able to function,” he adds.

By rights, it should be affected head teachers, senior, middle and business leaders, teaching staff and facilities managers who have most reason to be making expletive-laden comments about how well they’ve been coping with the RAAC ‘crumbly concrete’ emergency since the autumn.

CHRIS KIRKHAM-KNOWLES,

NAHT YORKSHIRE NATIONAL EXECUTIVE

COMMITTEE REPRESENTATIVE

They would, of course, all probably be much too professional to do so. Yet, as NAHT Yorkshire National Executive Committee representative Chris Kirkham-Knowles makes clear, the way school teams have come together and responded in adversity to this crisis needs – quite rightly – to be celebrated.

“What I’d like to get across is the amazing job the team is doing in terms of going above and beyond. And within that, I’m very much just a small cog,” he tells Leadership Focus.

Chris is the primary executive leader at Coast and Vale Academy, a multi-academy trust based in Scarborough that manages seven schools spread across North Yorkshire. One of these, Scalby School, a secondary with 1,000 students also in Scarborough, discovered earlier this year that it was 60% constructed out of RAAC, or ‘reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete’ to give it its full name.

“The school has known since the Department for Education (DfE) started to identify that RAAC surveys were needed. We go right back to January or February when this first all became apparent,” he explains.

“We were actually already undertaking mitigating works in the school over the summer. Before school broke up, there were already some corridors and rooms with props in them, albeit a small number. But at that point, the school was still able to function,” he adds.

Chris tells his school’s RAAC ‘journey’ more fully below – and it is, of course, far from complete and won’t be so for many years yet.

He is by no means the only head teacher – or NAHT member – to have faced what, for many, was a very rude wake-up call to the end of the summer holidays when on 31 August, just days before the return of children to schools, the DfE published its ‘new guidance for education settings’ on RAAC.

ANDY WALLS,

NAHT EDUCATIONAL ADVISER

What has most galled many working within education is there was, really, no need for things to be this last-minute. The DfE has long been aware that RAAC was something of a ticking timebomb for the school estate. Indeed, it had been trying to raise the alarm with the Treasury without success for some years, as NAHT educational adviser Andy Walls makes clear.

“The DfE has known about it for years,” he says. “It was highlighted on its risk register, its department’s flashing red light, a couple of years ago, precisely because of the ceiling collapse at a school in Gravesend in Kent in 2018 where, thankfully, because by chance it was on a Saturday, no one was injured.

“It was one of a long list of things needing attention on the school estate, including cladding and asbestos. But nothing much happened because there was no money to act on it; the DfE couldn’t get the money needed from the Treasury.

“There were three significant events over the summer where RAAC previously surveyed as being ‘non-critical’ failed. And so, the DfE suddenly realised that action needed to be taken. I’m glad the issue has been getting all this publicity without a major incident occurring,” Andy adds.

The other important point to emphasise here is that it is, again, thankfully, only a relatively small minority of schools (so far) that are directly affected.

Chris tells his school’s RAAC ‘journey’ more fully below – and it is, of course, far from complete and won’t be so for many years yet.

He is by no means the only head teacher – or NAHT member – to have faced what, for many, was a very rude wake-up call to the end of the summer holidays when on 31 August, just days before the return of children to schools, the DfE published its ‘new guidance for education settings’ on RAAC.

ANDY WALLS,

NAHT EDUCATIONAL ADVISER

What has most galled many working within education is there was, really, no need for things to be this last-minute. The DfE has long been aware that RAAC was something of a ticking timebomb for the school estate. Indeed, it had been trying to raise the alarm with the Treasury without success for some years, as NAHT educational adviser Andy Walls makes clear.

“The DfE has known about it for years,” he says. “It was highlighted on its risk register, its department’s flashing red light, a couple of years ago, precisely because of the ceiling collapse at a school in Gravesend in Kent in 2018 where, thankfully, because by chance it was on a Saturday, no one was injured.

“It was one of a long list of things needing attention on the school estate, including cladding and asbestos. But nothing much happened because there was no money to act on it; the DfE couldn’t get the money needed from the Treasury.

“There were three significant events over the summer where RAAC previously surveyed as being ‘non-critical’ failed. And so, the DfE suddenly realised that action needed to be taken. I’m glad the issue has been getting all this publicity without a major incident occurring,” Andy adds.

The other important point to emphasise here is that it is, again, thankfully, only a relatively small minority of schools (so far) that are directly affected.

According to the DfE, as of the last update on 16 October following surveys of several hundred schools, there are 217 schools and colleges where the presence of RAAC has been confirmed.

Of these, 202 settings still manage to provide face-to-face learning for all pupils and 12 have put hybrid arrangements in place. Some areas, though, such as Essex, have been particularly hard hit.

The corollary to this, of course, is teaching staff and school leaders in only a minority of schools have been directly affected, and only a minority of children have had their learning disrupted, while others have not. However, the fallout following the announcement (and the less-than-helpful comments from the secretary of state) has affected the entire sector.

The further important question still not fully clear is who pays a) for everything needed to put this all right and b) for all the extra costs (both day-to-day and in terms of extra capital spending) these schools are incurring through no fault of their own?

“There is a real need for the government to say what it is actually going to do and what that means, in practice, on the ground,” emphasises Andy Walls. “There have been a lot of fine words around ‘we’ll do everything it takes’ and ‘the safety of children is paramount’, but it is very light on ‘here is some new money’.

“There has been a massive under-investment in the capital estate since 2010. Building Schools for the Future under the last Labour government was a huge project, and the incoming coalition government just scrapped it. They have never really got funding back up to that level.

“It is basically like finally going to the dentist for a filling, but you haven’t been for 13 years, so of course, all your teeth are falling out. We at NAHT have been campaigning for a long time to get more capital funding into the school estate because it is quite simply falling apart at the seams,” Andy adds.

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

The need to get clarity for members about what’s happening and what’s going to happen has been an ongoing priority for NAHT as the crisis has unfolded, agrees NAHT assistant general secretary James Bowen.

“More than anything, we’ve been trying to collate and collect their questions and queries, get those into the DfE and then get answers for them as quickly as possible,” he emphasises. “Because, understandably, there’s a whole raft of questions that people have had. We have written a number of letters to the secretary of state to try to get answers. We’ve had numerous meetings with the DfE where we’ve been asking those questions and putting pressure on it.

“And we have had some achievements. At the beginning, for example, the DfE was saying it wouldn’t fund revenue costs, so things like if schools had extra costs for transport. We managed, with others, to persuade the DfE to change that so it would fund all reasonable revenue costs as well. That takes a bit of the financial pressure off for members worried about incurring additional costs. We are also now beginning to see the government honour its commitment to pay for the remedial works and things like temporary classrooms, which gives some reassurance, although we know we have to keep the pressure up.

“We will also continue to lobby the government to ensure that when long-term repairs are needed, they will all be funded centrally. Our advice team, too, has been going through all the questions that members have been asking to ensure the team is ready to answer all of those. We are also pressing the government to ensure that every school requiring a survey gets one without delay.

“We found that we needed to answer members’ questions on a one-to-one basis. The majority of our members are not directly affected by RAAC, thankfully. Those who are tend to have very specific questions. So, it has not been as simple as publishing a frequently asked questions document as we did for covid-19. We’ve found that each member has a unique situation, so the very best thing they can do is phone our advice line and speak to an advisor to get support,” James adds.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

Pressure on the government has also, of course, come from NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman. In September, for example, in an extensive blog to members, he outlined how NAHT had been pressing the government hard to clarify a range of issues around RAAC, particularly the actual extent of the problem.

“School staff are not structural engineers and have no expertise in this area. RAAC cannot readily be detected by just a visual inspection, and in some schools, it may be hard to access some of the spaces where it might be present,” he wrote.

“Where responsible bodies have indicated in responding to the DfE’s questionnaire that they are unsure if their schools have RAAC, the government must help organise further timely investigations using qualified experts.

“It appears that many schools are still awaiting structural surveys, meaning the number affected is likely to grow significantly. Schools seeking to minimise the wait by appointing their own surveyors may find that is easier said than done at a time when demand is so high.

“The DfE told the National Audit Office (NAO) in May that 8,600 of nearly 15,000 schools that might have RAAC had not been investigated at that point. Eight surveyors have been contracted by the government, and officials told the Education Select Committee last week that they are conducting 100 surveys a week. They reported two weeks ago that more than 600 schools had been surveyed.

“But the government has refused to say how many surveys are still to be completed or give a timeframe. At the time of writing, Ms Keegan [education secretary Gillian Keegan] has still not responded to questions from education unions to clarify this and update the NAO’s figures – or say how many schools are now suspected or deemed to be at risk of having RAAC.

“We have also had no response to our request for guidance on how school leaders should respond if they are unsure if their buildings are safe and who is responsible for decisions to evacuate or remove premises from use.

“Delays and lack of transparency are a concern for school leaders and, undoubtedly, for parents too. And the survey is just the first stage of a potentially disruptive process in which if the presence of RAAC is confirmed, temporary measures like installation of steel poles will be needed before more permanent repairs,” Paul added.

Of these, 202 settings still manage to provide face-to-face learning for all pupils and 12 have put hybrid arrangements in place. Some areas, though, such as Essex, have been particularly hard hit.

The corollary to this, of course, is teaching staff and school leaders in only a minority of schools have been directly affected, and only a minority of children have had their learning disrupted, while others have not. However, the fallout following the announcement (and the less-than-helpful comments from the secretary of state) has affected the entire sector.

The further important question still not fully clear is who pays a) for everything needed to put this all right and b) for all the extra costs (both day-to-day and in terms of extra capital spending) these schools are incurring through no fault of their own?

“There is a real need for the government to say what it is actually going to do and what that means, in practice, on the ground,” emphasises Andy Walls. “There have been a lot of fine words around ‘we’ll do everything it takes’ and ‘the safety of children is paramount’, but it is very light on ‘here is some new money’.

“There has been a massive under-investment in the capital estate since 2010. Building Schools for the Future under the last Labour government was a huge project, and the incoming coalition government just scrapped it. They have never really got funding back up to that level.

“It is basically like finally going to the dentist for a filling, but you haven’t been for 13 years, so of course, all your teeth are falling out. We at NAHT have been campaigning for a long time to get more capital funding into the school estate because it is quite simply falling apart at the seams,” Andy adds.

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

The need to get clarity for members about what’s happening and what’s going to happen has been an ongoing priority for NAHT as the crisis has unfolded, agrees NAHT assistant general secretary James Bowen.

“More than anything, we’ve been trying to collate and collect their questions and queries, get those into the DfE and then get answers for them as quickly as possible,” he emphasises. “Because, understandably, there’s a whole raft of questions that people have had. We have written a number of letters to the secretary of state to try to get answers. We’ve had numerous meetings with the DfE where we’ve been asking those questions and putting pressure on it.

“And we have had some achievements. At the beginning, for example, the DfE was saying it wouldn’t fund revenue costs, so things like if schools had extra costs for transport. We managed, with others, to persuade the DfE to change that so it would fund all reasonable revenue costs as well. That takes a bit of the financial pressure off for members worried about incurring additional costs. We are also now beginning to see the government honour its commitment to pay for the remedial works and things like temporary classrooms, which gives some reassurance, although we know we have to keep the pressure up.

“We will also continue to lobby the government to ensure that when long-term repairs are needed, they will all be funded centrally. Our advice team, too, has been going through all the questions that members have been asking to ensure the team is ready to answer all of those. We are also pressing the government to ensure that every school requiring a survey gets one without delay.

“We found that we needed to answer members’ questions on a one-to-one basis. The majority of our members are not directly affected by RAAC, thankfully. Those who are tend to have very specific questions. So, it has not been as simple as publishing a frequently asked questions document as we did for covid-19. We’ve found that each member has a unique situation, so the very best thing they can do is phone our advice line and speak to an advisor to get support,” James adds.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

Pressure on the government has also, of course, come from NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman. In September, for example, in an extensive blog to members, he outlined how NAHT had been pressing the government hard to clarify a range of issues around RAAC, particularly the actual extent of the problem.

“School staff are not structural engineers and have no expertise in this area. RAAC cannot readily be detected by just a visual inspection, and in some schools, it may be hard to access some of the spaces where it might be present,” he wrote.

“Where responsible bodies have indicated in responding to the DfE’s questionnaire that they are unsure if their schools have RAAC, the government must help organise further timely investigations using qualified experts.

“It appears that many schools are still awaiting structural surveys, meaning the number affected is likely to grow significantly. Schools seeking to minimise the wait by appointing their own surveyors may find that is easier said than done at a time when demand is so high.

“The DfE told the National Audit Office (NAO) in May that 8,600 of nearly 15,000 schools that might have RAAC had not been investigated at that point. Eight surveyors have been contracted by the government, and officials told the Education Select Committee last week that they are conducting 100 surveys a week. They reported two weeks ago that more than 600 schools had been surveyed.

“But the government has refused to say how many surveys are still to be completed or give a timeframe. At the time of writing, Ms Keegan [education secretary Gillian Keegan] has still not responded to questions from education unions to clarify this and update the NAO’s figures – or say how many schools are now suspected or deemed to be at risk of having RAAC.

“We have also had no response to our request for guidance on how school leaders should respond if they are unsure if their buildings are safe and who is responsible for decisions to evacuate or remove premises from use.

“Delays and lack of transparency are a concern for school leaders and, undoubtedly, for parents too. And the survey is just the first stage of a potentially disruptive process in which if the presence of RAAC is confirmed, temporary measures like installation of steel poles will be needed before more permanent repairs,” Paul added.

A further way NAHT has been holding ministers’ and officials’ feet to the fire is through direct members’ feedback. As James Bowen points out by way of example, soon after the crisis broke, NAHT cross-referenced the list of schools published by the DfE with its membership database. Members in affected schools were then personally emailed to ask if they needed help and signposted on how best to do so.

A snapshot survey was also carried out with affected members to gauge their experience, whether they were getting the support they needed from the DfE and what else they felt they needed.

“I was able to go to the DfE and say, ‘This is what our members are telling us, this is what else they need, and these are where their concerns lie’,” says James. “A lot of them, for example, were saying, ‘We don't know when we're going to get the temporary buildings, and we’re having problems getting hold of them’.

“We were able to go straight to the DfE and tell them members were not getting these buildings and ask what the timeline for sorting that out was. So, a lot of our role has simply been keeping the pressure up on the department,” he adds.

For Paul Whiteman, who spoke to Leadership Focus minutes after listening to prime minister Rishi Sunak’s address to the Conservative Party Conference in Manchester (dominated by the future of the HS2 high-speed rail line), RAAC is just another symbol of the Conservatives’ mismanagement and short-termism around investment decisions, especially capital infrastructure spending.

“Sunak announced in that speech that education will be the investment area for their economic strategy going forward. But on the RAAC issue, we have seen that coming for years and years and years, and yet the imposed austerity has meant that it has become a crisis – a crisis that has had to be managed,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“For the government suddenly to suggest that it is the only government that has thought education is an investment in the country’s future and that somehow it’s going to come riding over the hill to rescue it now sticks in the throat a bit. We’ve been arguing for at least the last 13 years that this Conservative government hasn’t invested. And yet, the point at which it begins to invest is only when schools are visibly crumbling, and it can no longer hide the effects of austerity from the eyes of parents and carers.

“We know from the DfE’s figures that it needs to rebuild about 200 schools a year to keep children in decent accommodation. We know that 700,000 children at the moment are taught in sub-standard accommodation. Yet the Treasury is only prepared to fund 50 buildings a year. So, the first thing the government has to do is step up to get to at least that 200 schools a year figure; otherwise, it will take 440 years to deal with the estate.

“If the government is really committed to this then, actually, we need to see an education budget where we can not only do the capital spends but also have the investment in education that we need over at least a decade and see that coming in a clear-sighted way. Let’s hope it’s not all just a smokescreen, and we end up disappointed in a few weeks’ time when we learn it was just a headline and nothing more,” Paul adds.

Either way, what schools affected by this crisis most need is a stable (and certainly not crumbling) foundation to build from for the future.

A further way NAHT has been holding ministers’ and officials’ feet to the fire is through direct members’ feedback. As James Bowen points out by way of example, soon after the crisis broke, NAHT cross-referenced the list of schools published by the DfE with its membership database. Members in affected schools were then personally emailed to ask if they needed help and signposted on how best to do so.

A snapshot survey was also carried out with affected members to gauge their experience, whether they were getting the support they needed from the DfE and what else they felt they needed.

“I was able to go to the DfE and say, ‘This is what our members are telling us, this is what else they need, and these are where their concerns lie’,” says James. “A lot of them, for example, were saying, ‘We don't know when we're going to get the temporary buildings, and we’re having problems getting hold of them’.

“We were able to go straight to the DfE and tell them members were not getting these buildings and ask what the timeline for sorting that out was. So, a lot of our role has simply been keeping the pressure up on the department,” he adds.

For Paul Whiteman, who spoke to Leadership Focus minutes after listening to prime minister Rishi Sunak’s address to the Conservative Party Conference in Manchester (dominated by the future of the HS2 high-speed rail line), RAAC is just another symbol of the Conservatives’ mismanagement and short-termism around investment decisions, especially capital infrastructure spending.

“Sunak announced in that speech that education will be the investment area for their economic strategy going forward. But on the RAAC issue, we have seen that coming for years and years and years, and yet the imposed austerity has meant that it has become a crisis – a crisis that has had to be managed,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“For the government suddenly to suggest that it is the only government that has thought education is an investment in the country’s future and that somehow it’s going to come riding over the hill to rescue it now sticks in the throat a bit. We’ve been arguing for at least the last 13 years that this Conservative government hasn’t invested. And yet, the point at which it begins to invest is only when schools are visibly crumbling, and it can no longer hide the effects of austerity from the eyes of parents and carers.

“We know from the DfE’s figures that it needs to rebuild about 200 schools a year to keep children in decent accommodation. We know that 700,000 children at the moment are taught in sub-standard accommodation. Yet the Treasury is only prepared to fund 50 buildings a year. So, the first thing the government has to do is step up to get to at least that 200 schools a year figure; otherwise, it will take 440 years to deal with the estate.

“If the government is really committed to this then, actually, we need to see an education budget where we can not only do the capital spends but also have the investment in education that we need over at least a decade and see that coming in a clear-sighted way. Let’s hope it’s not all just a smokescreen, and we end up disappointed in a few weeks’ time when we learn it was just a headline and nothing more,” Paul adds.

Either way, what schools affected by this crisis most need is a stable (and certainly not crumbling) foundation to build from for the future.

‘SCALBY SCHOOL ISN’T JUST ABOUT THE BRICKS AND MORTAR; WE’LL COME THROUGH THIS’

For Chris Kirkham-Knowles, dealing with the fallout (literally in some cases) from RAAC has become a full-time priority, even if – as he emphasises – he is just one part of a much wider team effort.

“My job is normally just two days a week part-time as the director of primary improvement. However, for the first month of the school year, I worked full-time within the leadership team at Scalby School to add capacity and to support the development of a school within a school for 210 year seven students," he tells Leadership Focus.

From, as we’ve already heard, a situation where there were just a number of rooms and areas that had to be propped up as a precaution, things escalated rapidly over the holiday period as the scale of the problem – and emergency – became clearer.

“Obviously, the 60% isn’t all in one area,” Chris explains. “So, you are in a situation where it is not as easy as just drawing a line and saying, ‘that part of the school can’t be used’. The school was built in the late 1940s/1950s, and it has had various additions over the years as it’s grown.

“Some of those additions have also got RAAC in them. But some of them haven’t. Yet, even if they haven’t, a number of them are infilled between bits with RAAC. Or they are external bits that you can’t get to without going through an RAAC-infested area, as it were.

“I had the privilege of the facilities manager showing me around because I wanted to see what this concrete actually looked like. She took me to the music room, which had technically been signed off as a ‘safe environment’ during two surveys. Part of the ceiling had been opened up to have a look, and they had determined that the RAAC visible in the roofing structure was safe.

“During the summer, when the risk level rose, they took the ceiling out and found that the RAAC panels actually ran the whole length of the room. They weren’t the shorter versions they had thought. And over the length of one of the panels, it had dropped by at least an inch-and-a-half in the middle.

“That illustrates the real difficulty of all this. To all intents and purposes, if you just took a part of the ceiling out, you could easily have said that the room was safe to be in – looking at just one small panel would not have given you an indication of the safety of the room. I’m absolutely no expert, but I certainly would not have wandered underneath that panel. From the safety of the doorway, it was quite clear to me it was not somewhere you wanted to go into,” Chris adds.

While safety had to be the immediate priority, the next was what to do – and what even was going to be possible – in terms of maintaining the learning for the children when they came back in September. For the medium term, the plan is to create a two-storey prefabricated ‘village’ on the school’s tennis courts to house the children. But this won’t be ready until the spring term at the earliest.

“At one time, it looked like everyone would need to wear hard hats and steel toe-capped boots just to get their pens, pencils and rulers out so they could go and teach somewhere else,” Chris points out.

“That happily didn’t happen. But, early on, we were worried we would only be able to offer something physically on site to year 11 students. And then we were looking at a remote learning offer for everybody else, using the lessons from covid-19.

“One of the advantages of being in a trust, however, is that we have other school sites. One, Scarborough UTC (University Technical College), said it had some extra capacity, seven classrooms that we’ve been able to repurpose for year seven students, so they at least get induction into secondary school life that isn’t a remote learning offer,” Chris explains, adding that years eight to 10 are now coming onto the site on a rota basis.

Yet even this temporary solution is not without its challenges or complications. “Our year seven students are effectively on a school visit for every day of their school life at the moment and will be for a considerable period until the ‘village’ goes up during the spring,” Chris says.

“They have to come to the secondary school initially because the UTC is on the other side of town. They are then put on three double-decker buses accompanied, of course, by staff. They go to the UTC, have their lessons, and when they leave at the end of the day, they come back to the secondary school. That means they have a truncated day, but at least they’re in a safe school environment,” he adds.

There is an added financial cost to all this – the ‘village’, the buses and even small things, such as ensuring adequate cutlery for this influx of much younger children (the UTC is for 14 to 18-year-olds). Chris’ extra hours, too, are an additional cost, and much more besides. Then there are the surveys and remedial works before we even get to talking about the cost of ‘fixing’ the problem, which will probably require the construction of a whole new school site.

“One quote alone for the scaffolding to go into the school, just for the year’s rental, for rooms that will never be used again and probably be demolished in time, came to the tune of £178,000. And that was just one of the quotes,” Chris points out.

As James Bowen alluded to earlier, Chris points out that the DfE has published a memorandum of understanding that has stated ‘reasonable’ costs accrued as a result of what is needed should be approved and covered. However, what this actually means in practice is still being debated, with invaluable specialist support coming from NAHT, not least from Andy Walls and assistant general secretary and solicitor Paula Porter.

“Having that sort of network behind you, in terms of that specialist support, in a situation this unknown, has been vital. Being able to pick up the phone and say, ‘Is there any chance of someone looking at this?’ to make sure we’re on the right lines has been hugely beneficial,” Chris points out.

Chris, however, is also scrupulous to point out that, for all the DfE’s faults and the criticisms it has incurred over this crisis, the DfE’s caseworker assigned to his school (one of around 80 across England) has been extremely helpful and useful.

"He has been second to none. So, we do need to celebrate what the DfE is doing in terms of providing on-the-ground support. The work that has been done since the end of August through to now has been fully supported by the DfE’s caseworker.

"We’ve also had visits from our local MP, the regional DfE director, education minister Baroness Barran and the regional schools commissioner, plus a number of other people," Chris emphasises.

This brings us back, in conclusion, to Scalby’s team, whom Chris cannot praise highly enough.

“In many respects, this is worse than the experience of covid-19 because, rather than all schools being affected, this is in isolation; it is in pockets. So, it is a very different beast. Parents can feel as if they are getting a really unfair deal. Keeping the parents on board has been hugely challenging, but brilliantly and really effectively done by the head teacher, Chris Robertson,” he emphasises.

“I also recall the first staff briefing when everyone came back in the autumn. One hundred and fifty staff members crammed into one room, and I was fortunate to be at the back listening in. Everyone was worried, and everyone had lots of questions. But I remember very clearly one teacher came up to Chris Robertson afterwards and said, ‘Scalby School isn’t just about the bricks and mortar; it’s about the students and the staff, and we’ll come through this’.

“What Chris Robertson has done subsequently is, very effectively, take that line and use it everywhere he has gone. There hasn’t been a point in time when the absolute focus of the leadership team in the school has been on anything other than providing as high a quality of education as the students can benefit from,” Chris adds.

‘SCALBY SCHOOL ISN’T JUST ABOUT THE BRICKS AND MORTAR; WE’LL COME THROUGH THIS’

For Chris Kirkham-Knowles, dealing with the fallout (literally in some cases) from RAAC has become a full-time priority, even if – as he emphasises – he is just one part of a much wider team effort.

“My job is normally just two days a week part-time as the director of primary improvement. However, for the first month of the school year, I worked full-time within the leadership team at Scalby School to add capacity and to support the development of a school within a school for 210 year seven students," he tells Leadership Focus.

From, as we’ve already heard, a situation where there were just a number of rooms and areas that had to be propped up as a precaution, things escalated rapidly over the holiday period as the scale of the problem – and emergency – became clearer.

“Obviously, the 60% isn’t all in one area,” Chris explains. “So, you are in a situation where it is not as easy as just drawing a line and saying, ‘that part of the school can’t be used’. The school was built in the late 1940s/1950s, and it has had various additions over the years as it’s grown.

“Some of those additions have also got RAAC in them. But some of them haven’t. Yet, even if they haven’t, a number of them are infilled between bits with RAAC. Or they are external bits that you can’t get to without going through an RAAC-infested area, as it were.

“I had the privilege of the facilities manager showing me around because I wanted to see what this concrete actually looked like. She took me to the music room, which had technically been signed off as a ‘safe environment’ during two surveys. Part of the ceiling had been opened up to have a look, and they had determined that the RAAC visible in the roofing structure was safe.

“During the summer, when the risk level rose, they took the ceiling out and found that the RAAC panels actually ran the whole length of the room. They weren’t the shorter versions they had thought. And over the length of one of the panels, it had dropped by at least an inch-and-a-half in the middle.

“That illustrates the real difficulty of all this. To all intents and purposes, if you just took a part of the ceiling out, you could easily have said that the room was safe to be in – looking at just one small panel would not have given you an indication of the safety of the room. I’m absolutely no expert, but I certainly would not have wandered underneath that panel. From the safety of the doorway, it was quite clear to me it was not somewhere you wanted to go into,” Chris adds.

While safety had to be the immediate priority, the next was what to do – and what even was going to be possible – in terms of maintaining the learning for the children when they came back in September. For the medium term, the plan is to create a two-storey prefabricated ‘village’ on the school’s tennis courts to house the children. But this won’t be ready until the spring term at the earliest.

“At one time, it looked like everyone would need to wear hard hats and steel toe-capped boots just to get their pens, pencils and rulers out so they could go and teach somewhere else,” Chris points out.

“That happily didn’t happen. But, early on, we were worried we would only be able to offer something physically on site to year 11 students. And then we were looking at a remote learning offer for everybody else, using the lessons from covid-19.

“One of the advantages of being in a trust, however, is that we have other school sites. One, Scarborough UTC (University Technical College), said it had some extra capacity, seven classrooms that we’ve been able to repurpose for year seven students, so they at least get induction into secondary school life that isn’t a remote learning offer,” Chris explains, adding that years eight to 10 are now coming onto the site on a rota basis.

Yet even this temporary solution is not without its challenges or complications. “Our year seven students are effectively on a school visit for every day of their school life at the moment and will be for a considerable period until the ‘village’ goes up during the spring,” Chris says.

“They have to come to the secondary school initially because the UTC is on the other side of town. They are then put on three double-decker buses accompanied, of course, by staff. They go to the UTC, have their lessons, and when they leave at the end of the day, they come back to the secondary school. That means they have a truncated day, but at least they’re in a safe school environment,” he adds.

There is an added financial cost to all this – the ‘village’, the buses and even small things, such as ensuring adequate cutlery for this influx of much younger children (the UTC is for 14 to 18-year-olds). Chris’ extra hours, too, are an additional cost, and much more besides. Then there are the surveys and remedial works before we even get to talking about the cost of ‘fixing’ the problem, which will probably require the construction of a whole new school site.

“One quote alone for the scaffolding to go into the school, just for the year’s rental, for rooms that will never be used again and probably be demolished in time, came to the tune of £178,000. And that was just one of the quotes,” Chris points out.

As James Bowen alluded to earlier, Chris points out that the DfE has published a memorandum of understanding that has stated ‘reasonable’ costs accrued as a result of what is needed should be approved and covered. However, what this actually means in practice is still being debated, with invaluable specialist support coming from NAHT, not least from Andy Walls and assistant general secretary and solicitor Paula Porter.

“Having that sort of network behind you, in terms of that specialist support, in a situation this unknown, has been vital. Being able to pick up the phone and say, ‘Is there any chance of someone looking at this?’ to make sure we’re on the right lines has been hugely beneficial,” Chris points out.

Chris, however, is also scrupulous to point out that, for all the DfE’s faults and the criticisms it has incurred over this crisis, the DfE’s caseworker assigned to his school (one of around 80 across England) has been extremely helpful and useful.

"He has been second to none. So, we do need to celebrate what the DfE is doing in terms of providing on-the-ground support. The work that has been done since the end of August through to now has been fully supported by the DfE’s caseworker.

"We’ve also had visits from our local MP, the regional DfE director, education minister Baroness Barran and the regional schools commissioner, plus a number of other people," Chris emphasises.

This brings us back, in conclusion, to Scalby’s team, whom Chris cannot praise highly enough.

“In many respects, this is worse than the experience of covid-19 because, rather than all schools being affected, this is in isolation; it is in pockets. So, it is a very different beast. Parents can feel as if they are getting a really unfair deal. Keeping the parents on board has been hugely challenging, but brilliantly and really effectively done by the head teacher, Chris Robertson,” he emphasises.

“I also recall the first staff briefing when everyone came back in the autumn. One hundred and fifty staff members crammed into one room, and I was fortunate to be at the back listening in. Everyone was worried, and everyone had lots of questions. But I remember very clearly one teacher came up to Chris Robertson afterwards and said, ‘Scalby School isn’t just about the bricks and mortar; it’s about the students and the staff, and we’ll come through this’.

“What Chris Robertson has done subsequently is, very effectively, take that line and use it everywhere he has gone. There hasn’t been a point in time when the absolute focus of the leadership team in the school has been on anything other than providing as high a quality of education as the students can benefit from,” Chris adds.