Small is beautiful

Journalist Nic Paton talks to rural school leaders about how they are making a difference within the education system and the communities they serve.

“You know everyone: all the children, the parents, grandparents and staff. You’re in a beautiful setting. You’re at the heart of your community, and it is your vision that directly makes a difference to the children, without it being watered down. No, even with all the challenges, I wouldn’t go back to working in a bigger school.”

Yet, as Ruhaina, executive head teacher of The Carey Federation – a maintained federation encompassing Halwill and Ashwater Primary Schools in villages in west Devon – also alludes to, it is a vocation that these days brings significant challenges. Challenges around funding, workload, pay, recruitment, retention and inspection. Challenges, moreover, that sometimes are not fully recognised or understood by the government, Ofsted or even, arguably, the wider profession.

NAHT’s report Under pressure was published earlier this year. It outlined how, on the one hand, small schools play a ‘vital and irreplaceable’ role in both the education system and in maintaining rural communities, especially as other hubs – the post office, the pub, the corner shop, the bank, the library, GP practice and even the church – increasingly disappear.

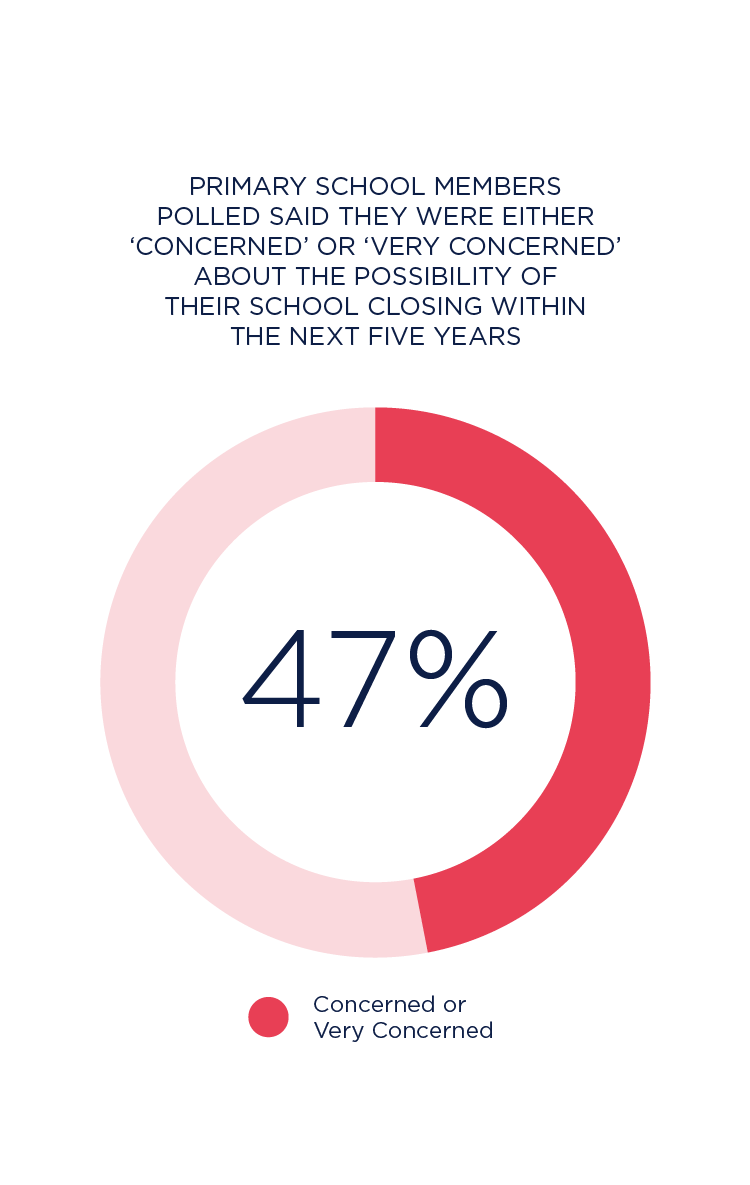

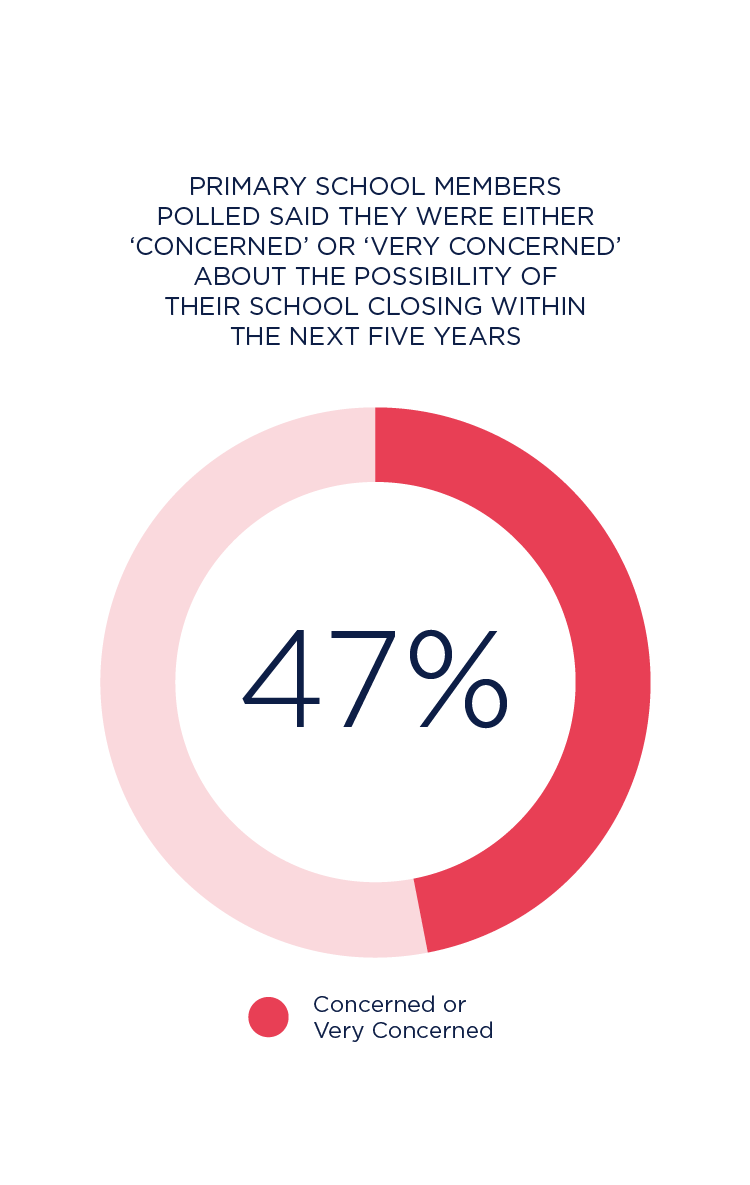

Yet, on the other hand, the financial situation in many such schools is now so precarious that nearly half (47%) of the small primary school members polled said they were either ‘concerned’ or ‘very concerned’ about the possibility of their school closing within the next five years, an increase of more than a tenth (12%) in just three years.

JULIE KELLY,

HEAD TEACHER, WEST MEON CHURCH

OF ENGLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL

“Yes, small schools are a particular beast and need a particular understanding. But they are in danger. If we’re not careful, they will start to disappear. In fact, they are starting to disappear,” warns Julie Kelly, head teacher of West Meon Church of England Primary School in Petersfield, Hampshire, and small schools lead on NAHT’s National Executive Committee.

“I am very worried about the future of small schools and their communities. In Hampshire, we’re having one a year start to close now, which we didn’t have before at all. Multi-academy trusts (MATs) might be one solution, but sometimes, small schools aren’t that attractive to MATs because of the budgets and the financing,” adds Julie, who is also head teacher liaison officer for the National Association of Small Schools.

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

“NAHT has been championing small schools for many, many years; it has been a long fight of ours,” emphasises NAHT assistant general secretary James Bowen.

“Because of the nature of our membership, we have a lot of members who work in small primary schools. So, it is very important that NAHT speaks up for them. Over the past few years, we have taken up several opportunities to bring small-school leaders to the Department for Education to speak directly to officials about how small school funding works.

“We’ve had opportunities to input into consultations. We’ve had some success in getting the government to improve the funding mechanisms for small and rural schools. Those changes have been small and incremental; nonetheless, NAHT should take pride in the fact that we’ve achieved those,” he adds.

What, then, precisely are these concerns, these particular challenges, that small schools face?

Yet, as Ruhaina, executive head teacher of The Carey Federation – a maintained federation encompassing Halwill and Ashwater Primary Schools in villages in west Devon – also alludes to, it is a vocation that these days brings significant challenges. Challenges around funding, workload, pay, recruitment, retention and inspection. Challenges, moreover, that sometimes are not fully recognised or understood by the government, Ofsted or even, arguably, the wider profession.

NAHT’s report Under pressure was published earlier this year. It outlined how, on the one hand, small schools play a ‘vital and irreplaceable’ role in both the education system and in maintaining rural communities, especially as other hubs – the post office, the pub, the corner shop, the bank, the library, GP practice and even the church – increasingly disappear.

Yet, on the other hand, the financial situation in many such schools is now so precarious that nearly half (47%) of the small primary school members polled said they were either ‘concerned’ or ‘very concerned’ about the possibility of their school closing within the next five years, an increase of more than a tenth (12%) in just three years.

JULIE KELLY,

HEAD TEACHER, WEST MEON CHURCH OF ENGLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL

“Yes, small schools are a particular beast and need a particular understanding. But they are in danger. If we’re not careful, they will start to disappear. In fact, they are starting to disappear,” warns Julie Kelly, head teacher of West Meon Church of England Primary School in Petersfield, Hampshire, and small schools lead on NAHT’s National Executive Committee.

“I am very worried about the future of small schools and their communities. In Hampshire, we’re having one a year start to close now, which we didn’t have before at all. Multi-academy trusts (MATs) might be one solution, but sometimes, small schools aren’t that attractive to MATs because of the budgets and the financing,” adds Julie, who is also head teacher liaison officer for the National Association of Small Schools.

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

“NAHT has been championing small schools for many, many years; it has been a long fight of ours,” emphasises NAHT assistant general secretary James Bowen.

“Because of the nature of our membership, we have a lot of members who work in small primary schools. So, it is very important that NAHT speaks up for them. Over the past few years, we have taken up several opportunities to bring small-school leaders to the Department for Education to speak directly to officials about how small school funding works.

“We’ve had opportunities to input into consultations. We’ve had some success in getting the government to improve the funding mechanisms for small and rural schools. Those changes have been small and incremental; nonetheless, NAHT should take pride in the fact that we’ve achieved those,” he adds.

What, then, precisely are these concerns, these particular challenges, that small schools face?

Taking funding first, as well as just not having enough money generally – something, of course, all schools face right now (not least when the government gets its sums wrong) – the issue for small schools is the fact that funding is (broadly) allocated based on the school roll.

NAHT helped to secure an improvement in how the ‘sparsity factor’ (which allocates additional money based on the number of pupils on roll and remoteness) is calculated – increasing the funding available and expanding the eligibility, resulting in 1,300 more schools receiving it. But the reality is that for a school with a small roll number, any fluctuation can have disproportionate consequences.

As James explains: “Our funding system in this country is still largely based around place numbers, around pupils, and that has a disproportionately negative impact on small schools. There are mechanisms that try to protect small schools – things like the lump sum. But fluctuations in numbers can really hamper small schools.

“For example, the ‘bulge’ in pupil numbers of a few years ago is now moving into secondary. We know this is affecting the primary sector more widely, but if you are a small school, that’s going to be much harder to absorb for obvious reasons.

“If you only have 40 children and you lose 10, you’ve suddenly lost a quarter of your roll. So, small schools will feel falling numbers on their roll particularly acutely. It could really be the difference between their budget being viable or not in the current context,” he points out.

RUHAINA ALFORD,

EXECUTIVE HEAD TEACHER, THE CAREY FEDERATION

“You can never be complacent because if one year you have a low birth rate, for example, it can have a real effect,” agrees Ruhaina Alford. In her case, Ashwater has 40 children, and Halwill has around 100.

“We’re very fortunate that although we were in deficit when I came, we now have balanced books with a carry forward. That’s partly through rationalising and looking at the spending, but it is also because we’ve been able to increase our pupil numbers,” she says.

“We are very rural, generally quite an agricultural catchment, particularly in Ashwater, though we do have a changing profile because post-pandemic, more people have moved in from the south-east – people who are working remotely or just want a new lifestyle,” she adds.

MAYLEEN ATIMA,

HEAD TEACHER, BEAUMONT COMMUNITY

PRIMARY SCHOOL IN HADLEIGH, IPSWICH

With just 88 children currently on the roll, which has fluctuated quite widely in recent years, future funding is something Mayleen Atima, head teacher of Beaumont Community Primary School in Hadleigh, Ipswich, is having to think about very carefully.

“We are about 60% service children and closely linked as a school to the Royal Air Force (RAF) Wattisham, so we have high mobility. The highest we’ve had on roll was 130 pupils the year after covid-19. We were around 100 for a number of years. However, the number at the moment is the lowest it has been, and this is largely because we’ve had a lot of families moving on,” she points out.

“Since covid-19, I think it has become worse for everyone. We’re all trying to achieve the same things. However, smaller schools are doing it with less, with fewer staff members and resources. So, you have to be really creative in a small school. I’m always looking for freebies and grants; I've become a master at writing grant applications!

“But the falling roll number means I have to think about our staffing. We have a census coming up next week and I’m very aware that, with 88 kids, it means next year our funding is going to be much lower.

“At the moment, we’re not at the point where we have to lose teachers because we’ve always operated on the assumption that we’re only going to have about 15 children in each cohort. But in reception at the moment, we just have eight children. In year six, it’s 10,” Mayleen adds ominously.

NAHT helped to secure an improvement in how the ‘sparsity factor’ (which allocates additional money based on the number of pupils on roll and remoteness) is calculated – increasing the funding available and expanding the eligibility, resulting in 1,300 more schools receiving it. But the reality is that for a school with a small roll number, any fluctuation can have disproportionate consequences.

As James explains: “Our funding system in this country is still largely based around place numbers, around pupils, and that has a disproportionately negative impact on small schools. There are mechanisms that try to protect small schools – things like the lump sum. But fluctuations in numbers can really hamper small schools.

“For example, the ‘bulge’ in pupil numbers of a few years ago is now moving into secondary. We know this is affecting the primary sector more widely, but if you are a small school, that’s going to be much harder to absorb for obvious reasons.

“If you only have 40 children and you lose 10, you’ve suddenly lost a quarter of your roll. So, small schools will feel falling numbers on their roll particularly acutely. It could really be the difference between their budget being viable or not in the current context,” he points out.

RUHAINA ALFORD,

EXECUTIVE HEAD TEACHER, THE CAREY FEDERATION

“You can never be complacent because if one year you have a low birth rate, for example, it can have a real effect,” agrees Ruhaina Alford. In her case, Ashwater has 40 children, and Halwill has around 100.

“We’re very fortunate that although we were in deficit when I came, we now have balanced books with a carry forward. That’s partly through rationalising and looking at the spending, but it is also because we’ve been able to increase our pupil numbers,” she says.

“We are very rural, generally quite an agricultural catchment, particularly in Ashwater, though we do have a changing profile because post-pandemic, more people have moved in from the south-east – people who are working remotely or just want a new lifestyle,” she adds.

MAYLEEN ATIMA,

HEAD TEACHER, BEAUMONT COMMUNITY

PRIMARY SCHOOL IN HADLEIGH, IPSWICH

With just 88 children currently on the roll, which has fluctuated quite widely in recent years, future funding is something Mayleen Atima, head teacher of Beaumont Community Primary School in Hadleigh, Ipswich, is having to think about very carefully.

“We are about 60% service children and closely linked as a school to the Royal Air Force (RAF) Wattisham, so we have high mobility. The highest we’ve had on roll was 130 pupils the year after covid-19. We were around 100 for a number of years. However, the number at the moment is the lowest it has been, and this is largely because we’ve had a lot of families moving on,” she points out.

“Since covid-19, I think it has become worse for everyone. We’re all trying to achieve the same things. However, smaller schools are doing it with less, with fewer staff members and resources. So, you have to be really creative in a small school. I’m always looking for freebies and grants; I've become a master at writing grant applications!

“But the falling roll number means I have to think about our staffing. We have a census coming up next week and I’m very aware that, with 88 kids, it means next year our funding is going to be much lower.

“At the moment, we’re not at the point where we have to lose teachers because we’ve always operated on the assumption that we’re only going to have about 15 children in each cohort. But in reception at the moment, we just have eight children. In year six, it’s 10,” Mayleen adds ominously.

This can often be exacerbated by the rural nature of the environment, meaning public transport options may be limited if they exist at all.

“There is only a certain pool of people for you to draw on when you’re talking about small communities,” points out Ruhaina Alford. “Particularly here in Devon, we just don’t have the transport links. You might have two buses a day where you live or, in some places, no buses at all. For support staff roles in particular, which are so, so important, it can be really difficult.”

“We can’t get an extra lunchtime supervisor because we are so rural, and with the cost of living, are people going to be able to afford to pay the petrol to get here?” agrees Julie Kelly.

“The bus services have disappeared, and so they can’t get here for the hour to be a lunchtime supervisor. So, I’m doing that as well at the moment. Schools around us are having problems getting teaching assistants because, again, with the cost of living, they can get paid more working in a shop,” she adds.

Julie’s comment, ‘So, I’m doing that as well at the moment’, is telling and important here. Because, in a small school environment, struggles with funding and recruitment will – almost inevitably – be fed back onto the shoulders of the head teacher.

In many small schools, there won’t be a deputy head teacher, let alone a school business manager or even, sometimes, a facilities manager. Julie, for example, came rushing to her chat with Leadership Focus straight from lunchtime duty because of her school’s current inability to hire a lunchtime supervisor.

At West Meon Church of England, the school has 59 children split between three classes, approximately 20 in each. “I’m the lead on personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) education and PE. I have a very long-term supply teacher leading on art, and design and technology (DT),” Julie points out.

“Of the three class teachers, one of them is still being trained through the school-centred initial teacher training (SCITT) programme but is keeping an eye for us on maths and computing. My other one has just finished her early career teacher (ECT) training, and the third one is about to become an ECT. In an ideal world, they, of course, shouldn’t really be leading on subjects. But they’re having to because there isn’t really anyone else to do it,” she points out.

“I have duties during the day, and I’m on duty every morning – and I tend to be out there at the end of the day as well. I organise all the sports, games and intra-school sports, which might involve me loading up the car and taking the pupils and all their kit to the other school. I also take the children swimming in January and February.

“I drive the minibus, and that’s another thing that has come up recently. I’m old enough to drive it, but on the driving licence for younger people, you don’t necessarily have the qualification to drive a minibus.

“I lead a residential in year five, so leave my lead teacher in charge. But she and the other teacher are coming in the evenings because I can’t be there alone. And then, when year six goes on residential, I’m there every night because they can’t be there alone in the evening,” Julie adds.

“In my small school, I’m head teacher, I’m the maths lead, and I’m the education visits lead,” agrees Mayleen Atima. “My office manager has just left, so I’m now running the office; I’m also the relationships and sex education (RSE) and PE lead. I'm still trying to make sure those subjects are being taught properly and to a high standard while monitoring everything.

“We’ve recently been fortunate enough to be able to recruit a caretaker but, for a while, I was doing that too; I was locking and closing up. Once or twice, I’ve had to vacuum and help out the cleaning staff. It is not just about classrooms but also the facilities and pretty much everything else,” she adds.

This, in turn, generates a huge burden in terms of responsibility for head teachers, especially the feeling they can’t afford to be unwell, take time off or even carve out a healthy work-life balance.

“Head teachers like me, we thrive on it,” admits Julie. “But there are also days when you're just totally exhausted by the end of it. If I’m not in, if I’m unwell, then that is a problem. If it was just one day, they could probably get by, but if I were off too long, it would cause a problem.

“If I were off next week, for example, there would be no one to take my classes on Monday afternoon, and supply teachers are getting harder and harder to find. Someone would have to be a lunchtime supervisor. There would be no one to run the chess club. There’s a governors’ meeting in the evening. Then, as the week goes on, it would just get worse,” she points out. “In the last year, I was able to recruit a deputy,” highlights Mayleen. “I said to my governors that it was just becoming too much, just how thinly I was spreading myself.

“If I’m feeling slightly unwell, I think, ‘but who’s going to do X, Y or Z?’ So, I tend to drag myself in. This Friday, for example, I’ve decided that I’m finally going to have a day working from home. But who will answer the phones in the office?” she adds, very much echoing Julie Kelly.

Despite all this, and arguably to add insult to injury, pay levels for small-school head teachers tend to be lower than for their bigger-school counterparts, again because this is normally based on roll size, as James Bowen highlights. “Often small-school leaders will say there is a real unfairness around pay,” he says.

“Yet the job is still the job. They have all the Ofsted pressures, they have all the pressure around SATs, and they have all the pressure around parents and governors – it is all the same amount of work; in fact, they’re probably doing extra stuff because they might not have a deputy head teacher to fall back on. And yet they’re paid less because they have a smaller roll.”

“I’m earning less than I was as a deputy head teacher in London, even though that was an independent school,” agrees Ruhaina Alford. “The pay is lower because you’re at a lower end of the threshold on the pay scale.”

“You have to love it to do it; it is not a job you do for the money,” adds Mayleen Atima. “You have to have a passion for seeing your children achieve and have these great experiences. And you can have a huge role in their lives. You can have a real impact if you create the right school environment.”

This can often be exacerbated by the rural nature of the environment, meaning public transport options may be limited if they exist at all.

“There is only a certain pool of people for you to draw on when you’re talking about small communities,” points out Ruhaina Alford. “Particularly here in Devon, we just don’t have the transport links. You might have two buses a day where you live or, in some places, no buses at all. For support staff roles in particular, which are so, so important, it can be really difficult.”

“We can’t get an extra lunchtime supervisor because we are so rural, and with the cost of living, are people going to be able to afford to pay the petrol to get here?” agrees Julie Kelly.

“The bus services have disappeared, and so they can’t get here for the hour to be a lunchtime supervisor. So, I’m doing that as well at the moment. Schools around us are having problems getting teaching assistants because, again, with the cost of living, they can get paid more working in a shop,” she adds.

Julie’s comment, ‘So, I’m doing that as well at the moment’, is telling and important here. Because, in a small school environment, struggles with funding and recruitment will – almost inevitably – be fed back onto the shoulders of the head teacher.

In many small schools, there won’t be a deputy head teacher, let alone a school business manager or even, sometimes, a facilities manager. Julie, for example, came rushing to her chat with Leadership Focus straight from lunchtime duty because of her school’s current inability to hire a lunchtime supervisor.

At West Meon Church of England, the school has 59 children split between three classes, approximately 20 in each. “I’m the lead on personal, social, health and economic (PSHE) education and PE. I have a very long-term supply teacher leading on art, and design and technology (DT),” Julie points out.

“Of the three class teachers, one of them is still being trained through the school-centred initial teacher training (SCITT) programme but is keeping an eye for us on maths and computing. My other one has just finished her early career teacher (ECT) training, and the third one is about to become an ECT. In an ideal world, they, of course, shouldn’t really be leading on subjects. But they’re having to because there isn’t really anyone else to do it,” she points out.

“I have duties during the day, and I’m on duty every morning – and I tend to be out there at the end of the day as well. I organise all the sports, games and intra-school sports, which might involve me loading up the car and taking the pupils and all their kit to the other school. I also take the children swimming in January and February.

“I drive the minibus, and that’s another thing that has come up recently. I’m old enough to drive it, but on the driving licence for younger people, you don’t necessarily have the qualification to drive a minibus.

“I lead a residential in year five, so leave my lead teacher in charge. But she and the other teacher are coming in the evenings because I can’t be there alone. And then, when year six goes on residential, I’m there every night because they can’t be there alone in the evening,” Julie adds.

“In my small school, I’m head teacher, I’m the maths lead, and I’m the education visits lead,” agrees Mayleen Atima. “My office manager has just left, so I’m now running the office; I’m also the relationships and sex education (RSE) and PE lead. I'm still trying to make sure those subjects are being taught properly and to a high standard while monitoring everything.

“We’ve recently been fortunate enough to be able to recruit a caretaker but, for a while, I was doing that too; I was locking and closing up. Once or twice, I’ve had to vacuum and help out the cleaning staff. It is not just about classrooms but also the facilities and pretty much everything else,” she adds.

This, in turn, generates a huge burden in terms of responsibility for head teachers, especially the feeling they can’t afford to be unwell, take time off or even carve out a healthy work-life balance.

“Head teachers like me, we thrive on it,” admits Julie. “But there are also days when you're just totally exhausted by the end of it. If I’m not in, if I’m unwell, then that is a problem. If it was just one day, they could probably get by, but if I were off too long, it would cause a problem.

“If I were off next week, for example, there would be no one to take my classes on Monday afternoon, and supply teachers are getting harder and harder to find. Someone would have to be a lunchtime supervisor. There would be no one to run the chess club. There’s a governors’ meeting in the evening. Then, as the week goes on, it would just get worse,” she points out. “In the last year, I was able to recruit a deputy,” highlights Mayleen. “I said to my governors that it was just becoming too much, just how thinly I was spreading myself.

“If I’m feeling slightly unwell, I think, ‘but who’s going to do X, Y or Z?’ So, I tend to drag myself in. This Friday, for example, I’ve decided that I’m finally going to have a day working from home. But who will answer the phones in the office?” she adds, very much echoing Julie Kelly.

Despite all this, and arguably to add insult to injury, pay levels for small-school head teachers tend to be lower than for their bigger-school counterparts, again because this is normally based on roll size, as James Bowen highlights. “Often small-school leaders will say there is a real unfairness around pay,” he says.

“Yet the job is still the job. They have all the Ofsted pressures, they have all the pressure around SATs, and they have all the pressure around parents and governors – it is all the same amount of work; in fact, they’re probably doing extra stuff because they might not have a deputy head teacher to fall back on. And yet they’re paid less because they have a smaller roll.”

“I’m earning less than I was as a deputy head teacher in London, even though that was an independent school,” agrees Ruhaina Alford. “The pay is lower because you’re at a lower end of the threshold on the pay scale.”

“You have to love it to do it; it is not a job you do for the money,” adds Mayleen Atima. “You have to have a passion for seeing your children achieve and have these great experiences. And you can have a huge role in their lives. You can have a real impact if you create the right school environment.”

INSPECTION

As James Bowen highlights, small-school head teachers will rightly face the same inspection and accountability rigours as their bigger-school counterparts. The problem, he adds, is that Ofsted’s inspection framework hasn’t historically been well suited to recognise or accommodate the ways small schools operate – the fact, very simply, that they are so small.

“The current Ofsted framework was largely designed through a secondary school lens,” he explains. “That can be challenging for primary schools, but even more acutely challenging for small primary schools. For example, the handbook almost expects you to have subject specialists with departments. That just isn’t the case in a primary school; in a very small primary school, you can have the thing where the teacher is the subject leader for six subjects,” James adds.

“If you only have four teachers and the same subjects to lead, you contrast this with an inspector going into a secondary school, and they say, ‘I’d like to interview the geography lead and do a deep dive into their curriculum’. That geography lead may have a number of teachers in their department and is a geography specialist with a geography degree.

“You, however, go to a small school and say, ‘I'd like to speak to the geography lead’, and the geography lead will also be the history, science, music and modern foreign languages lead. So, it is trying to juggle all of those.

“These are widely different contexts that the inspector is walking into. Ofsted has started to recognise this, and NAHT has been pushing at this hard. But that chasm between large secondary schools and small rural primary schools is so huge, just making that single framework work for those small schools is really difficult,” James adds.

‘Pushing at this hard’ in this context has meant that NAHT has been working with Ofsted on a working group to review and potentially rethink at least parts of the inspection framework for small schools. So far, things have been positive, with NAHT and Ofsted holding a series of monthly meetings, points out Julie Kelly, who is a member of the working group.

“I am very heartened by the meetings I’ve had so far with Ofsted. We’re having monthly meetings until the January training period for its inspectors. Ofsted is really, really looking at this closely now to make sure its inspectors understand before they go into small schools,” she tells Leadership Focus.

“Part of that is a big, big focus on the curriculum because there are so few teachers in small schools yet so many areas of the curriculum to cover. Part of this learning process is them all going into small schools to look at how they operate and get feedback, just going in, learning and doing research. And then to come back and talk to us,” she adds.

“In a tiny school, during an inspection, everyone is seen multiple times,” agrees Ruhaina Alford. “In a large school, you might not be seen at all. Although we had a one-day short inspection, it was still two inspectors inspecting two classes.

“So, you go from the inspector having a conversation with a group of children, those children going straight back into class, and then the same children being observed. But to be fair, the inspectors very much took that on board, and they were very good,” she adds.

INSPECTION

As James Bowen highlights, small-school head teachers will rightly face the same inspection and accountability rigours as their bigger-school counterparts. The problem, he adds, is that Ofsted’s inspection framework hasn’t historically been well suited to recognise or accommodate the ways small schools operate – the fact, very simply, that they are so small.

“The current Ofsted framework was largely designed through a secondary school lens,” he explains. “That can be challenging for primary schools, but even more acutely challenging for small primary schools. For example, the handbook almost expects you to have subject specialists with departments. That just isn’t the case in a primary school; in a very small primary school, you can have the thing where the teacher is the subject leader for six subjects,” James adds.

“If you only have four teachers and the same subjects to lead, you contrast this with an inspector going into a secondary school, and they say, ‘I’d like to interview the geography lead and do a deep dive into their curriculum’. That geography lead may have a number of teachers in their department and is a geography specialist with a geography degree.

“You, however, go to a small school and say, ‘I'd like to speak to the geography lead’, and the geography lead will also be the history, science, music and modern foreign languages lead. So, it is trying to juggle all of those.

“These are widely different contexts that the inspector is walking into. Ofsted has started to recognise this, and NAHT has been pushing at this hard. But that chasm between large secondary schools and small rural primary schools is so huge, just making that single framework work for those small schools is really difficult,” James adds.

‘Pushing at this hard’ in this context has meant that NAHT has been working with Ofsted on a working group to review and potentially rethink at least parts of the inspection framework for small schools. So far, things have been positive, with NAHT and Ofsted holding a series of monthly meetings, points out Julie Kelly, who is a member of the working group.

“I am very heartened by the meetings I’ve had so far with Ofsted. We’re having monthly meetings until the January training period for its inspectors. Ofsted is really, really looking at this closely now to make sure its inspectors understand before they go into small schools,” she tells Leadership Focus.

“Part of that is a big, big focus on the curriculum because there are so few teachers in small schools yet so many areas of the curriculum to cover. Part of this learning process is them all going into small schools to look at how they operate and get feedback, just going in, learning and doing research. And then to come back and talk to us,” she adds.

“In a tiny school, during an inspection, everyone is seen multiple times,” agrees Ruhaina Alford. “In a large school, you might not be seen at all. Although we had a one-day short inspection, it was still two inspectors inspecting two classes.

“So, you go from the inspector having a conversation with a group of children, those children going straight back into class, and then the same children being observed. But to be fair, the inspectors very much took that on board, and they were very good,” she adds.

HEART OF THE COMMUNITY

So far, we’ve focused almost solely on the challenges and difficulties small-school head teachers face. But, if Ruhaina Alford’s comments at the beginning show us anything, there can also be huge rewards to leading a small rural school (just maybe not financial ones).

“It is hard to overstate just how important some small and rural schools have become for their communities,” emphasises James Bowen. “In some communities, they really are the last public service standing. It is through the school that many of these communities are held together. People come together for the summer fair, the school fete and the meeting by the school gates; they really are the hub of these communities.

“If these schools disappear, it means children being bussed miles and miles away from their local communities. Every parent I’ve spoken to, what do they want for their children? They want a local school they can walk or get to easily; they don’t want their children bussed miles and miles away. If we start looking at school amalgamations, you can lose that. Children are being taken out of their communities and educated elsewhere, and that's not good for those communities either,” James adds.

“Having visited many small schools, there is something very unique and special about them. You go to a school with only 40 or 50 children, there is a family-like feel. That nurturing feeling is so important for some children, particularly those with additional needs. Some families will actively seek out a smaller school precisely for that. Some children get lost or overwhelmed in a bigger environment.

“One of the things that strikes me about school leaders who work in small schools is that they become passionate advocates for them. Every school leader I have ever known who’s worked in a small school becomes a huge advocate for them. They see the power that small schools can bring, and they see the difference they make. Probably more so than leaders who work in other schools,” James adds.

“I love the whole ethos of small schools, the family ethos, and the fact you know all the children and all the parents,” agrees Julie Kelly. “We are very integral to the village. It is one of those villages that used to have two pubs; it now only has one. There used to be a village shop; volunteers now run that. What else is here? If you don't have a school, families won’t move to the area. You just get older and older people in the village. You are the centre of the community.

“Lots of people say they walk into the school and they can feel it straight away, they can feel the friendliness. Of course, everyone is going to say that about their school. But I’ve been a deputy head teacher in a school of 600, and you can't get to know every child. I’m not saying those children aren’t known by their teachers, but as a head teacher, I know everybody’s name, and I say good morning to them and use their names every morning. It is a close-knit community, and we are a strong part of it,” she adds.

CLOSENESS TO NATURE

The beautiful rural Devon setting of Ashwater and Halwill schools is something that Ruhaina Alford very much celebrates. “I feel it also makes a huge difference to behaviour and well-being. As part of the children’s learning, we embrace Wild Tribe outdoor learning; we link it into the curriculum.

“So, for example, if the children are learning about World War Two and rationing, we take them outside to learn about growing foods. Every child at Halwill will get a term of Wild Tribe within the year, and at Ashwater, they get half a year. They get it all the way from nursery up to year six.

“There is a really strong sense of community within and outside the school. All the children know each other, and you get a strong sense of the older children nurturing the younger. They look out for them, and the younger children learn from the older ones, which is also a real positive for behaviour,” Ruhaina adds.

“In the mixed-age classes, you never need to worry about the older children being pulled back; it is the opposite. The older children actually raise the bar for the younger children. So, if you have a child who needs a little bit more support, you can give that. With the parents and staff, too, because we all know each other, they feel comfortable approaching me if they have any concerns,” says Ruhaina.

HEART OF THE COMMUNITY

So far, we’ve focused almost solely on the challenges and difficulties small-school head teachers face. But, if Ruhaina Alford’s comments at the beginning show us anything, there can also be huge rewards to leading a small rural school (just maybe not financial ones).

“It is hard to overstate just how important some small and rural schools have become for their communities,” emphasises James Bowen. “In some communities, they really are the last public service standing. It is through the school that many of these communities are held together. People come together for the summer fair, the school fete and the meeting by the school gates; they really are the hub of these communities.

“If these schools disappear, it means children being bussed miles and miles away from their local communities. Every parent I’ve spoken to, what do they want for their children? They want a local school they can walk or get to easily; they don’t want their children bussed miles and miles away. If we start looking at school amalgamations, you can lose that. Children are being taken out of their communities and educated elsewhere, and that's not good for those communities either,” James adds.

“Having visited many small schools, there is something very unique and special about them. You go to a school with only 40 or 50 children, there is a family-like feel. That nurturing feeling is so important for some children, particularly those with additional needs. Some families will actively seek out a smaller school precisely for that. Some children get lost or overwhelmed in a bigger environment.

“One of the things that strikes me about school leaders who work in small schools is that they become passionate advocates for them. Every school leader I have ever known who’s worked in a small school becomes a huge advocate for them. They see the power that small schools can bring, and they see the difference they make. Probably more so than leaders who work in other schools,” James adds.

“I love the whole ethos of small schools, the family ethos, and the fact you know all the children and all the parents,” agrees Julie Kelly. “We are very integral to the village. It is one of those villages that used to have two pubs; it now only has one. There used to be a village shop; volunteers now run that. What else is here? If you don't have a school, families won’t move to the area. You just get older and older people in the village. You are the centre of the community.

“Lots of people say they walk into the school and they can feel it straight away, they can feel the friendliness. Of course, everyone is going to say that about their school. But I’ve been a deputy head teacher in a school of 600, and you can't get to know every child. I’m not saying those children aren’t known by their teachers, but as a head teacher, I know everybody’s name, and I say good morning to them and use their names every morning. It is a close-knit community, and we are a strong part of it,” she adds.

CLOSENESS TO NATURE

The beautiful rural Devon setting of Ashwater and Halwill schools is something that Ruhaina Alford very much celebrates. “I feel it also makes a huge difference to behaviour and well-being. As part of the children’s learning, we embrace Wild Tribe outdoor learning; we link it into the curriculum.

“So, for example, if the children are learning about World War Two and rationing, we take them outside to learn about growing foods. Every child at Halwill will get a term of Wild Tribe within the year, and at Ashwater, they get half a year. They get it all the way from nursery up to year six.

“There is a really strong sense of community within and outside the school. All the children know each other, and you get a strong sense of the older children nurturing the younger. They look out for them, and the younger children learn from the older ones, which is also a real positive for behaviour,” Ruhaina adds.

“In the mixed-age classes, you never need to worry about the older children being pulled back; it is the opposite. The older children actually raise the bar for the younger children. So, if you have a child who needs a little bit more support, you can give that. With the parents and staff, too, because we all know each other, they feel comfortable approaching me if they have any concerns,” says Ruhaina.

LOOKING FOR ANSWERS

While the great things about small rural schools clearly don’t need fixing – and, if anything, maybe there are some lessons for others, even in bigger schools, to take away and learn from – when it comes to the challenges, what are the solutions here? And what needs to be NAHT’s role within this?

“At a very simple and basic level, I think it is about getting either this government or any future governments to commit to small and rural schools fully and not move to a policy of amalgamation and closure unless it is utterly unavoidable,” emphasises James Bowen. “So, it’s about having a very visible, a very public, commitment to small and rural schools.

“When you speak to local MPs, they absolutely see the power of small schools. Often, it is the local MPs lobbying the hardest on behalf of small schools. But then you get to departmental or national level, and suddenly they’re far less warm towards them because they see them as being less cost-effective for some reason.

“I’d also like to see two other things. One, I want the next government to review the funding mechanism and the funding formula to make sure small schools are getting a fair proportion of the overall funding.

“Two, I think we have to review the Ofsted framework properly. The working group is a good start, but the current handbook simply does not work for small primary schools. We have to look again, particularly at this idea of deep dives with curriculum experts in small schools. That is just not working,” James adds.

“For me, it is about NAHT acknowledging that we – small schools – are here, acknowledging that we mustn’t let them disappear as the nurseries have,” emphasises Julie Kelly.

“I would like our members to recognise more that we really care about small schools, to know that there are small-school head teachers on NAHT’s National Executive Committee and that NAHT is working to push solutions around things like funding and workload in small schools. Finally, I feel we need to be doing more to nurture the leaders coming up so that there are people to replace all of us who are retiring,” Julie adds.

Through its advice line, NAHT does provide small and rural school head teachers with much-needed support and guidance, emphasises adviser Joanne Richardson, who herself ran a small school. Key concerns that come up frequently include the ongoing lack of resources, funding, recruitment, admission numbers and space availability, she points out.

“Members know they are held accountable by their local authority (or trust if they are in a MAT) and that no account is given to the fact their time is so constrained and they have so many other responsibilities. We talk issues through with them and try to find a way forward,” she says.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

“Small schools are so key to their local communities,” emphasises NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman in conclusion. “They might be small, but they are the heart of their local community, which is so, so important.

“Part of our job at NAHT is ensuring the government doesn’t forget that. Particularly in those schools facing falling roll numbers and other difficulties, we need to emphasise that they should be looked after and cared for as much as any of the bigger schools that may surround them in bigger conurbations.

“Within that, of course, small rural schools very much need to be celebrated, too. We need, absolutely, to celebrate the flexibility of the staff and their ability – including the head teacher – to be able to do everything and go that extra mile. Small rural schools are constantly a feature in our discussion and policy formation, and long may that continue,” Paul adds.

LOOKING FOR ANSWERS

While the great things about small rural schools clearly don’t need fixing – and, if anything, maybe there are some lessons for others, even in bigger schools, to take away and learn from – when it comes to the challenges, what are the solutions here? And what needs to be NAHT’s role within this?

“At a very simple and basic level, I think it is about getting either this government or any future governments to commit to small and rural schools fully and not move to a policy of amalgamation and closure unless it is utterly unavoidable,” emphasises James Bowen. “So, it’s about having a very visible, a very public, commitment to small and rural schools.

“When you speak to local MPs, they absolutely see the power of small schools. Often, it is the local MPs lobbying the hardest on behalf of small schools. But then you get to departmental or national level, and suddenly they’re far less warm towards them because they see them as being less cost-effective for some reason.

“I’d also like to see two other things. One, I want the next government to review the funding mechanism and the funding formula to make sure small schools are getting a fair proportion of the overall funding.

“Two, I think we have to review the Ofsted framework properly. The working group is a good start, but the current handbook simply does not work for small primary schools. We have to look again, particularly at this idea of deep dives with curriculum experts in small schools. That is just not working,” James adds.

“For me, it is about NAHT acknowledging that we – small schools – are here, acknowledging that we mustn’t let them disappear as the nurseries have,” emphasises Julie Kelly.

“I would like our members to recognise more that we really care about small schools, to know that there are small-school head teachers on NAHT’s National Executive Committee and that NAHT is working to push solutions around things like funding and workload in small schools. Finally, I feel we need to be doing more to nurture the leaders coming up so that there are people to replace all of us who are retiring,” Julie adds.

Through its advice line, NAHT does provide small and rural school head teachers with much-needed support and guidance, emphasises adviser Joanne Richardson, who herself ran a small school. Key concerns that come up frequently include the ongoing lack of resources, funding, recruitment, admission numbers and space availability, she points out.

“Members know they are held accountable by their local authority (or trust if they are in a MAT) and that no account is given to the fact their time is so constrained and they have so many other responsibilities. We talk issues through with them and try to find a way forward,” she says.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

“Small schools are so key to their local communities,” emphasises NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman in conclusion. “They might be small, but they are the heart of their local community, which is so, so important.

“Part of our job at NAHT is ensuring the government doesn’t forget that. Particularly in those schools facing falling roll numbers and other difficulties, we need to emphasise that they should be looked after and cared for as much as any of the bigger schools that may surround them in bigger conurbations.

“Within that, of course, small rural schools very much need to be celebrated, too. We need, absolutely, to celebrate the flexibility of the staff and their ability – including the head teacher – to be able to do everything and go that extra mile. Small rural schools are constantly a feature in our discussion and policy formation, and long may that continue,” Paul adds.

‘I WOULDN’T WANT TO DO

THIS FOR ANYWHERE ELSE’

SARAH MCDOWELL, PRINCIPAL OF ST PATRICK'S PRIMARY SCHOOL LEGAMADDY, NEAR DOWNPATRICK IN NORTHERN IRELAND

Apart from a year of teaching in Australia immediately after leaving university, principal Sarah McDowell has devoted her 23-year career to St Patrick’s Primary School Legamaddy in Northern Ireland. “I know the parents, grandparents, childminders and aunties – everyone!” she laughs.

The school, near the town of Downpatrick, has 164 pupils, eight teachers and 16 classroom assistants and is very much at the heart of a tight-knit rural community. “Our classroom staff, the majority of them, too, are from the community here,” Sarah tells Leadership Focus.

“So, they also have an amazing, vested interest in the school and the children. Our community links are fabulous; we're very well-respected. Any events we run in the school – our Christmas plays, Halloween trails and children’s assemblies, for example – are always well attended. The community comes out in droves to support us, which is just fabulous.

“We have very close links with our parish because we are a Catholic school. The parishioners love to see the children coming into the church. And we, in turn, have a parish group that comes into the school. We also have a reading-together programme, inviting parents and grandparents to come in to read with the kids. We are very community-based and always try to involve the community in everything we do.

“We have one pub and a chapel but no post office; we are a really rural community. It is a very beautiful area, and farms surround us. The children can watch the seasons change, the lambing, the cows in the fields and the tractors going past; the children tell us when the silage needs cutting and the different things that need to happen throughout the seasons. We have some stables out here, and the horses go past daily, which the children love,” Sarah adds.

“As the head teacher of a small school, you take on the role, but it is an umbrella of roles. It is very much a vocation. Every day, I come to school and have a list of things to do in my diary. But I might not even get to open my diary during the day. It could be blocked toilets, somebody’s sick, a branch has fallen off the tree, or the swing has broken.

“You definitely have to have the personality to be able to let things go. I've learnt over the years that you have to sometimes just draw the line, stop thinking about it and move on. There’s always so much you could do.

“Today, for example, we had someone coming in doing some electrical wiring, so I was there setting up safety zones. There are always a million things to do and so many staff to manage. Managing people effectively is really hard; just having the time to chat with them properly. Everybody has something going on every single day, and you want to touch base with people for their mental health.

“At times, it can be a lonely role as well. There is a risk that you try to carry the whole workload because you don’t want to ask people for help. I have got much better at delegating over the years! But everything does stop with me. So, you have to be careful not to divide yourself too much.

“But I wouldn’t want to do this for anywhere else. We have generation after generation coming through; my three children have been through this school, too. The kids that I’m teaching now, I’ve taught many of their parents. It is so lovely to see them coming back in. They know how we teach them; they know how all the children will be welcomed and nurtured. So, we have great relationships,” Sarah concludes.

SMALL SCHOOLS UNDER PRESSURE

According to NAHT’s report ‘Under pressure: the financial squeeze on small schools in England’, nearly half (47%) of the respondents were concerned about their small school’s possible closure.

For the report, published in January this year, NAHT surveyed 360 members in small primary schools. Worryingly, the 47% figure represented an increase of more than a tenth (12%) in just three years since NAHT had last asked the question.

Three-quarters (75%) of the members polled reported that a lack of funding was a factor contributing to the possibility of closure. More than eight in 10 (82%) identified low or fluctuating pupil numbers as a contributory factor to possible closure, underlining the impact of cyclical demographic changes as the pupil ‘bulge’ moves to the secondary phase.

More than two-thirds (68%) of participants reported that their school’s financial position had worsened or significantly worsened since the 2019 study, with schools facing ‘a perfect storm’ of financial pressures. This included the government's failure to provide sufficient funding for special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) provision, the impact of rapidly rising energy bills and unfunded pay awards.

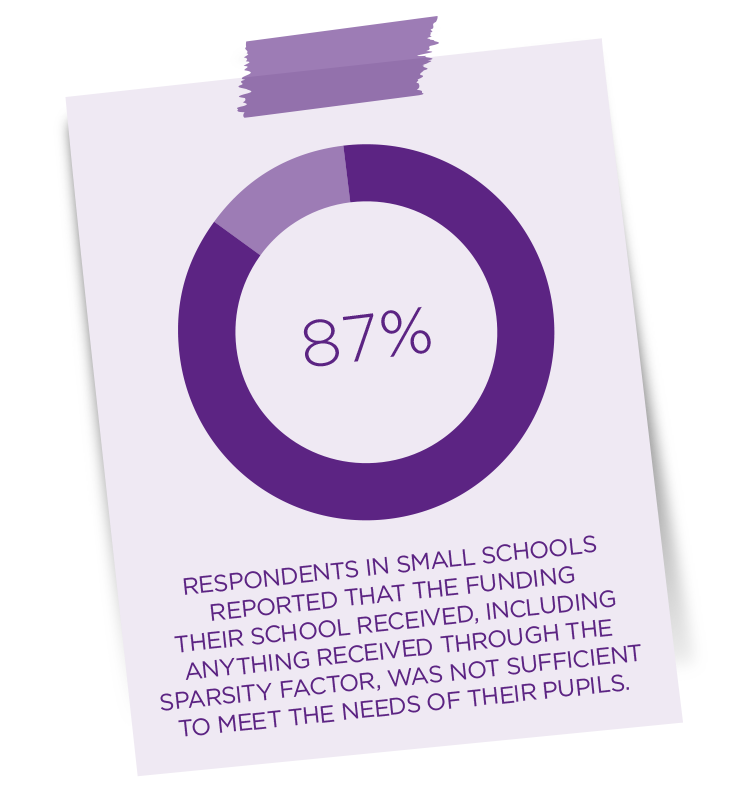

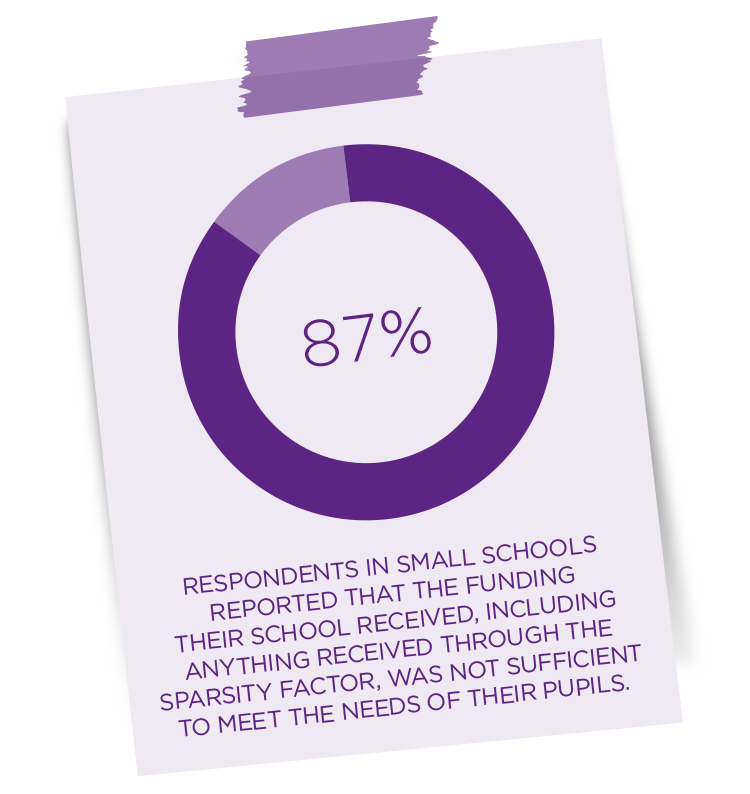

Almost nine in 10 (87%) respondents in small schools reported that the funding their school received, including anything received through the sparsity factor, was not sufficient to meet the needs of their pupils.

In response, more than two-thirds (67%) of senior leaders in small schools who responded to the survey had increased their teaching commitment. More than half (56%) had reduced the number or hours of their teaching assistants. More than a third (37%) had reduced non-educational support and services for children.

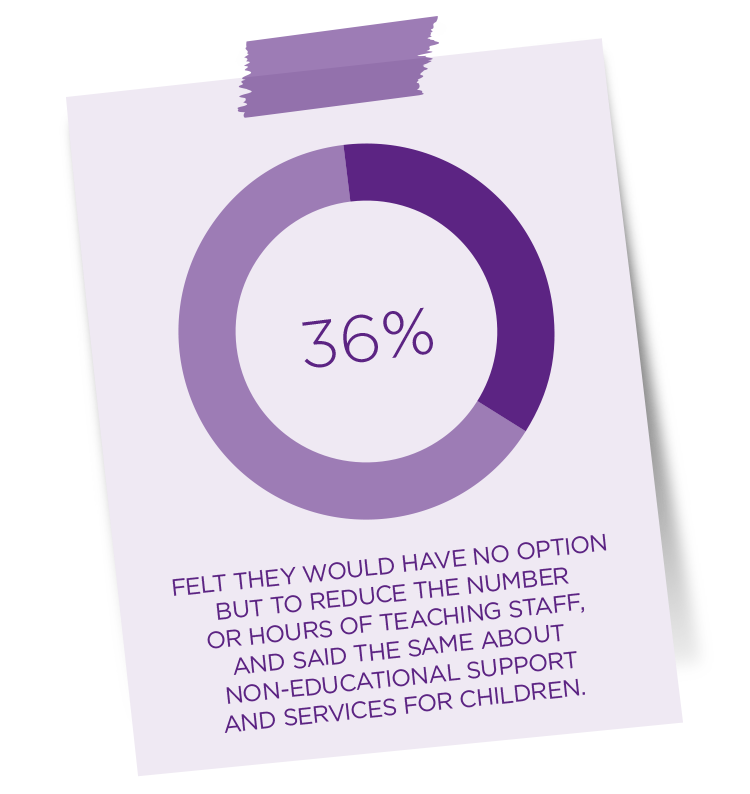

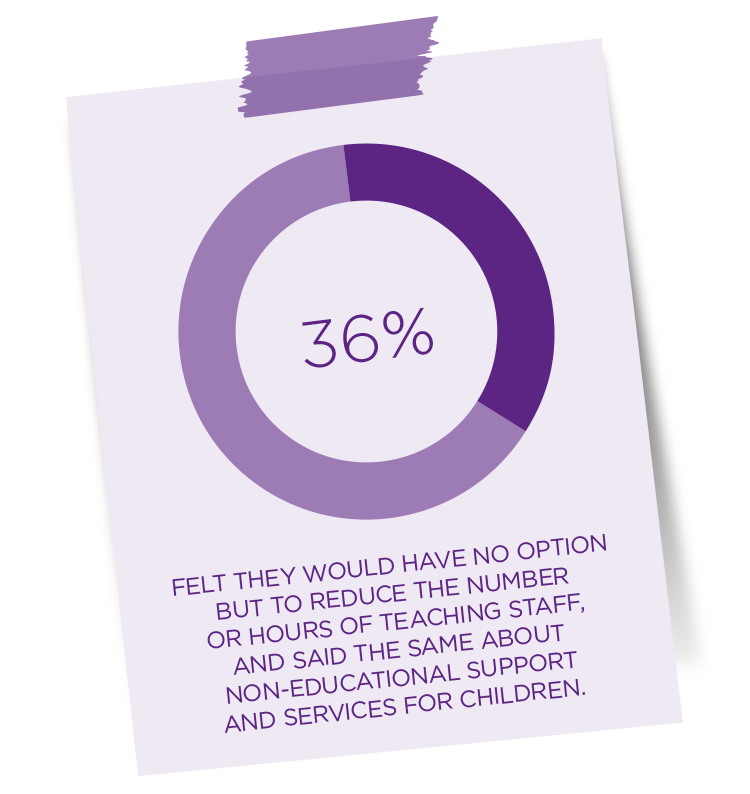

Equally, almost half (47%) said that in the future, they would have to reduce the number or hours of teaching assistants. More than a third (36%) felt they would have no option but to reduce the number or hours of teaching staff, and more than a third (36%) said the same about non-educational support and services for children.

A number also raised concerns about the cost of maintaining increasingly dilapidated school buildings. More than four in 10 (41%) who were concerned about the possibility of closure of their school reported that the upkeep of their school’s estate and buildings was a contributory factor.

More than half (53%) had reduced their maintenance budget over the past three years, and more than a third (37%) anticipated reducing expenditure on maintenance over the next three years.

SMALL SCHOOLS UNDER PRESSURE

According to NAHT’s report ‘Under pressure: the financial squeeze on small schools in England’, nearly half (47%) of the respondents were concerned about their small school’s possible closure.

For the report, published in January this year, NAHT surveyed 360 members in small primary schools. Worryingly, the 47% figure represented an increase of more than a tenth (12%) in just three years since NAHT had last asked the question.

Three-quarters (75%) of the members polled reported that a lack of funding was a factor contributing to the possibility of closure. More than eight in 10 (82%) identified low or fluctuating pupil numbers as a contributory factor to possible closure, underlining the impact of cyclical demographic changes as the pupil ‘bulge’ moves to the secondary phase.

More than two-thirds (68%) of participants reported that their school’s financial position had worsened or significantly worsened since the 2019 study, with schools facing ‘a perfect storm’ of financial pressures. This included the government's failure to provide sufficient funding for special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) provision, the impact of rapidly rising energy bills and unfunded pay awards.

Almost nine in 10 (87%) respondents in small schools reported that the funding their school received, including anything received through the sparsity factor, was not sufficient to meet the needs of their pupils.

In response, more than two-thirds (67%) of senior leaders in small schools who responded to the survey had increased their teaching commitment. More than half (56%) had reduced the number or hours of their teaching assistants. More than a third (37%) had reduced non-educational support and services for children.

Equally, almost half (47%) said that in the future, they would have to reduce the number or hours of teaching assistants. More than a third (36%) felt they would have no option but to reduce the number or hours of teaching staff, and more than a third (36%) said the same about non-educational support and services for children.

A number also raised concerns about the cost of maintaining increasingly dilapidated school buildings. More than four in 10 (41%) who were concerned about the possibility of closure of their school reported that the upkeep of their school’s estate and buildings was a contributory factor.

More than half (53%) had reduced their maintenance budget over the past three years, and more than a third (37%) anticipated reducing expenditure on maintenance over the next three years.