Leadership Focus journalist Nic Paton looks at the corrosive impact the current pay situation is having on the profession.

This year, buried within NAHT’s evidence on pay to the independent School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB) are statistics that should ring alarm bells for all head teachers and school leaders concerned about the future, and future health, of school leadership.

The report, published and submitted to the STRB last month (March), has set out detailed arguments as to why, this year, things desperately need to change when it comes to head teachers’ and school leaders’ pay. Why, after years of stagnation and erosion, there needs to be a reset of – in effect, a new settlement around – school leaders’ pay. And we will come to what NAHT is calling for this year in more detail shortly.

The corrosive impact the current pay situation is having on the ground in terms of school leaders voting with their feet, deciding enough is enough and leaving the profession – so-called ‘wastage rates’ – is now alarming many in the profession.

This year, buried within NAHT’s evidence on pay to the independent School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB) are statistics that should ring alarm bells for all head teachers and school leaders concerned about the future, and future health, of school leadership.

The report, published and submitted to the STRB last month (March), has set out detailed arguments as to why, this year, things desperately need to change when it comes to head teachers’ and school leaders’ pay. Why, after years of stagnation and erosion, there needs to be a reset of – in effect, a new settlement around – school leaders’ pay. And we will come to what NAHT is calling for this year in more detail shortly.

The corrosive impact the current pay situation is having on the ground in terms of school leaders voting with their feet, deciding enough is enough and leaving the profession – so-called ‘wastage rates’ – is now alarming many in the profession.

NAHT secured evidence through a freedom of information request, which shows that wastage rates have increased in every school leadership category when comparing 2011/15 to 2015/20 data.

To give a flavour, the percentage of primary head teachers appointed to post in 2011 who then left within five years was 22%. But for those appointed in 2015, it was 25%. For secondary head teachers, it was 35% in 2011 and 37% in 2015.

These figures may seem relatively small in themselves, but as the evidence also suggests, they may simply be the calm before the storm of a much larger pandemic-related exodus.

As the report states: “It’s also worth noting that the impact of the pandemic interrupted the 2020 and 2021 recruitment rounds; evidence suggests that many experienced teachers and leaders have delayed career decisions, which may have artificially improved the five-year retention rate for the period 2015/20.”

These fears for the future were starkly laid out in NAHT’s recent report, ‘Fixing the leadership crisis: time for change’. The report, the result of a survey of more than 2,000 NAHT members, concluded that dissatisfaction is rising steeply within the profession, with fewer than a third (30%) of school leaders now saying they’d recommend school leadership as a career goal (a fall of 36% in a single year).

More than half of assistant and deputy head teachers (53%) now say they don’t aspire to headship, with more than a fifth (23%) remaining undecided. A lack of professional recognition and trust, unsustainable workload and high-stakes inspection were all driving attrition and undermining aspiration to lead (see more on the report's findings).

These figures may seem relatively small in themselves, but as the evidence also suggests, they may simply be the calm before the storm of a much larger pandemic-related exodus.

As the report states: “It’s also worth noting that the impact of the pandemic interrupted the 2020 and 2021 recruitment rounds; evidence suggests that many experienced teachers and leaders have delayed career decisions, which may have artificially improved the five-year retention rate for the period 2015/20.”

These fears for the future were starkly laid out in NAHT’s recent report, ‘Fixing the leadership crisis: time for change’. The report, the result of a survey of more than 2,000 NAHT members, concluded that dissatisfaction is rising steeply within the profession, with fewer than a third (30%) of school leaders now saying they’d recommend school leadership as a career goal (a fall of 36% in a single year).

More than half of assistant and deputy head teachers (53%) now say they don’t aspire to headship, with more than a fifth (23%) remaining undecided. A lack of professional recognition and trust, unsustainable workload and high-stakes inspection were all driving attrition and undermining aspiration to lead (see more on the report's findings).

These were fears that also ran through an NAHT virtual panel discussion held in February precisely to discuss ways we may be able to ‘fix’ school leaders’ pay.

STUART SMITH,

HEAD TEACHER AT ST MARY'S PRIMARY SCHOOL

As Stuart Smith – head teacher at St Mary’s Primary School, a two-form entry primary school in Birmingham, and one of the panellists – put it: “We could be looking at a quite significant exodus over the next two to three years of highly experienced head teachers, with fewer people coming up behind them because the financial incentives aren’t there. I’m very worried about the future and how pay fits into that.”

Superficially, of course, chancellor Rishi Sunak’s pledge in the autumn to end the schoolteachers’ pay freeze was notionally good news for the sector. However, it simply masks – indeed could exacerbate – longstanding problems around school leaders’ and head teachers’ pay.

First, against a backdrop of rising inflation and the burgeoning cost-of-living crisis, it remains moot whether teachers will receive anything close to a rise that can mitigate fast-growing prices, let alone restore teachers’ pay after years of stagnation.

Second, this is even more the case for school leaders and head teachers, who have seen their pay fall in real terms over the past decade. Indeed, this year’s evidence makes the point that, since 2010, the salary of a school leader in percentage terms has declined by 15% against consumer prices index (CPI) inflation and a massive 27% against retail prices index (RPI) inflation.

IAN HARTWRIGHT,

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISOR

To restore school leaders’ pay while at the same time meeting the government’s ambition of lifting newly qualified teachers’ (NQTs’) starting salaries to £30,000 by (probably) 2024 will require a succession of inflation-busting pay rises for those further up the scale, as NAHT senior policy advisor Ian Hartwright makes clear to Leadership Focus.

“In practice, this will mean an 8% salary rise this year and a further 8% the next, and fully funded to ensure this extra money is not eked out of already stretched school budgets. I accept we run the risk of being pilloried in the likes of the Daily Mail by asking for 16% across two years. But this is what’s needed to even get you back to salaries of 2010 levels. Asking for less just seems to be an unsustainable thing to do,” he says.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

In realpolitik terms, the likelihood of this sort of financial largesse being waved through the Treasury is unlikely. However, the consequences of not significantly loosening the purse strings could be severe, as NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman emphasises.

“The only way to position it, to talk to the government about it, is that first of all, the government should be absolutely ashamed of its record on pay in the education sector. The government can’t blame it on anybody else; it has had its hands on this for over a decade now,” he says.

“Everybody has warned the government that this is coming. The STRB has told the government too, and it has ignored the STRB and ignored some of the recommendations that have come from it.

“What we’re saying is that the government has to make a significant step now so that it can begin to put the brakes on the retention and recruitment crisis. Then it needs to work with us to build a proposition over the next few years that takes us back to a more solid footing for pay and reward in education.

“We know the issue of pay can’t be repaired overnight, but let’s have at least a big step in the right direction – one that gives a strong signal of intent – which we can then build on over the next two to three years,” Paul adds.

STUART SMITH,

HEAD TEACHER AT ST MARY'S PRIMARY SCHOOL

As Stuart Smith – head teacher at St Mary’s Primary School, a two-form entry primary school in Birmingham, and one of the panellists – put it: “We could be looking at a quite significant exodus over the next two to three years of highly experienced head teachers, with fewer people coming up behind them because the financial incentives aren’t there. I’m very worried about the future and how pay fits into that.”

Superficially, of course, chancellor Rishi Sunak’s pledge in the autumn to end the schoolteachers’ pay freeze was notionally good news for the sector. However, it simply masks – indeed could exacerbate – longstanding problems around school leaders’ and head teachers’ pay.

First, against a backdrop of rising inflation and the burgeoning cost-of-living crisis, it remains moot whether teachers will receive anything close to a rise that can mitigate fast-growing prices, let alone restore teachers’ pay after years of stagnation.

Second, this is even more the case for school leaders and head teachers, who have seen their pay fall in real terms over the past decade. Indeed, this year’s evidence makes the point that, since 2010, the salary of a school leader in percentage terms has declined by 15% against consumer prices index (CPI) inflation and a massive 27% against retail prices index (RPI) inflation.

IAN HARTWRIGHT,

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISOR

To restore school leaders’ pay while at the same time meeting the government’s ambition of lifting newly qualified teachers’ (NQTs’) starting salaries to £30,000 by (probably) 2024 will require a succession of inflation-busting pay rises for those further up the scale, as NAHT senior policy advisor Ian Hartwright makes clear to Leadership Focus.

“In practice, this will mean an 8% salary rise this year and a further 8% the next, and fully funded to ensure this extra money is not eked out of already stretched school budgets. I accept we run the risk of being pilloried in the likes of the Daily Mail by asking for 16% across two years. But this is what’s needed to even get you back to salaries of 2010 levels. Asking for less just seems to be an unsustainable thing to do,” he says.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

In realpolitik terms, the likelihood of this sort of financial largesse being waved through the Treasury is unlikely. However, the consequences of not significantly loosening the purse strings could be severe, as NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman emphasises.

“The only way to position it, to talk to the government about it, is that first of all, the government should be absolutely ashamed of its record on pay in the education sector. The government can’t blame it on anybody else; it has had its hands on this for over a decade now,” he says.

“Everybody has warned the government that this is coming. The STRB has told the government too, and it has ignored the STRB and ignored some of the recommendations that have come from it.

“What we’re saying is that the government has to make a significant step now so that it can begin to put the brakes on the retention and recruitment crisis. Then it needs to work with us to build a proposition over the next few years that takes us back to a more solid footing for pay and reward in education.

“We know the issue of pay can’t be repaired overnight, but let’s have at least a big step in the right direction – one that gives a strong signal of intent – which we can then build on over the next two to three years,” Paul adds.

Alongside this, NAHT is making a firm case for school business leaders to get a better deal. The evidence has called for ‘a thorough review’ of the leadership pay structure for school business leaders, adding: “NAHT believes that the pay and conditions of school business leaders should be aligned with a revised leadership pay range.”

A complementary NAHT report, ‘School business leadership in crisis? Making school business leadership sustainable’, in January echoed the concerns of the ‘Fixing the leadership crisis’ report. It found the number of school business leaders who would recommend school leadership had fallen by 10% between 2020 and 2021, from 48% to 43%.

HILARY GOLDSMITH,

SCHOOL BUSINESS LEADER AT THE JUDD SCHOOL

According to Hilary Goldsmith, school business leader with The Judd School in Tonbridge, Kent and a member of NAHT’s school business leaders’ sector council, the pressures and pinch-points faced by school business leaders are similar, and similarly corrosive, to those experienced by head teachers and other school leaders.

“From the school business leaders’ (SBLs’) side, we need to have an alignment with leadership salaries. This is, first, to attract and, second, to retain school business leaders as part of the senior leadership team. The media and the Department for Education’s communications are all about ‘schools’ and ‘teachers’; they don’t often talk about school leadership. So, school leadership as a ‘thing’, as a concept, has become very blurry,” she told NAHT’s February virtual panel.

As with other school leaders, pay progression was also an issue for SBLs, Hilary pointed out. “The responsibilities that come with school leadership have grown so hugely over the last few years. The gap between an administrator and finance manager, stepping into a truly strategic role and the responsibilities that come with that, is massive but with very little additional recognition,” Hilary added.

STUART SMITH,

HEAD TEACHER AT ST MARY'S PRIMARY SCHOOL

The erosion and stagnation of school leaders’ pay is not just fuelling an exodus at the top; it is becoming a key factor in deterring middle or senior leaders from stepping up to headship or more senior roles, as the ‘Fixing the leadership crisis’ report made clear. Essentially, the intense accountability and workload pressures that come with headship are becoming increasingly unattractive when combined with the fact there is so little extra reward to compensate.

As Stuart Smith, again, highlighted in our panel discussion: “It’s the recruitment of future leaders that, I think, is critical for the sector. When I talk to younger colleagues, I see and hear people who had – and I’m going to use the past tense – aspirations to become head teachers in the future.

“We have potential leaders of the future looking at the sheer range of responsibilities that head teachers have, the accountability that goes with that and the lack of financial incentives. And they don’t see any reason, at this moment in time, to take that final step,” he added.

CLAIRE EVANS,

HEAD TEACHER AT ETON VALLEY PRIMARY SCHOOL

The need for a reformed national pay structure (with mandatory minimum pay points) and pay portability is critical because the narrowing of pay differentials is an important factor in this reluctance to move up. The aspiration for NQTs to have a starting salary of £30,000 simply serves to add insult to the lack of financial progression for people moving into more senior roles.

The impact of a lack of a proper pay continuum or progression was brought into sharp focus in the discussion by Claire Evans, who took on the head teacher role at Eaton Valley Primary School, a two-form entry school in West Bromwich, last September.

“I went from a deputy head in a larger school in Birmingham to Eaton Valley,” she said. “When I was looking for a headship position, it was hard to find something equal to what I was being paid as a deputy. A lot of the two-form entry headships I was looking at would have meant a drop in salary,” she said.

“When I was offered the job here and the grade was lower than what I was on as a deputy, I asked whether they would just match it, and that felt uncomfortable. That leap from deputy to head teacher sometimes is negligible in terms of the pay – none of us does it for the pay, but it would be nice to be rewarded for it,” Claire added.

CHRIS KIRKHAM-KNOWLES,

PRIMARY EXECUTIVE LEADER AT COAST AND VALE LEARNING TRUST

The need for greater codification and definition of executive leadership roles, especially against the backdrop of the academisation and federalisation of the school system, was highlighted by Chris Kirkham-Knowles, the primary executive leader at Coast and Vale Learning Trust in North Yorkshire and chair of NAHT’s professional committee.

“I think heads or senior leaders in small schools face a specific challenge around their pay and remuneration, particularly with the trend towards federation and working across a number of schools. The STPCD isn’t clear about how those people should be remunerated,” he told the panel discussion.

For example, as the head teacher of a small school, you may have a relatively low number of pupils, yet still as much – if not more – responsibility as a head of a larger school, he pointed out. The rollout of multi-academy trusts (MATs), perhaps spread across a number of very different small schools and/or across a wide geographical or rural area (such as, in his area, North Yorkshire), simply amplified the problem.

“It is a very specialised job when it comes to meeting the needs of communities that can differ from one Dale to the next, despite their schools being on each other’s doorsteps. I think there is a particular challenge there in terms of getting it right for school leaders and making sure that people see those roles as attractive ones,” Chris said.

“The clarity of progression is another challenge. The STPCD and the terms and conditions haven’t kept pace with the changes that academisation, federation and other structures have introduced. My job, for example, is one of them. My job isn’t covered by any national negotiation; it has almost been invented as a pay scale. I have no idea where I’d go next if I were looking for career progression. There has been no move towards clarifying any sort of progression,” Chris continued.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

Clearly, there is a compelling argument – and appetite – for change within the profession. But is the government prepared to listen and what happens next, especially if it’s not?

Of course, whether the government is prepared to listen is a question that only the government ultimately can answer. Paul Whiteman, however, emphasises that it is beholden on NAHT and the other teaching unions to at least try to get ministers to hear.

“Our first step has to be reasoned argument with the government. The government has allowed it to get like this; it has to step up now. We have to try to persuade the government that this will be a popular thing to do. Yes, we will get our detractors – but saving education when you, the government, have placed education, correctly, in the centre of the country’s recovery involves making sure you look after those leading it,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“We also have to persuade the STRB to have the confidence of its mission and to stand up and say what’s in front of its face. Don’t, for example, be guided by the government to say, ‘within the bounds of affordability’. Simply state (based on the evidence it receives) what the pay rate should be.

“I think, within this, we need to be having quite an in-depth conversation with the STRB and the government about pay system reform within education. It is a frightening prospect for some, I recognise; the idea of having a conversation around national pay scales, local pay systems, pay freedoms and all the rest of it,” Paul continues.

As to the second ‘what happens next?’ question, there are two strands: the technical, practical process and then a wider, more existential conversation.

The technical, practical process is straightforward enough. The report has now gone to the STRB. There follows a period to submit supplementary evidence. After which, NAHT will give oral evidence to the STRB, which then submits its recommendations to the secretary of state, who is the decision-maker.

Once again, the timeframe is running seriously behind this year, so the deadlines are extremely tight. Theoretically, an announcement on pay should be made before September, but this is likely to run late again – perhaps even into December, says Ian Hartwright.

As to the second strand – what NAHT and the profession can or should do in response to an intransigent or simply belligerent government – that is, naturally, more challenging. Are we hurtling, irrevocably, towards a fracturing of relations and, even, the prospect of industrial action if things don’t improve or if the warnings of the profession are not heeded?

“For me, as the system has become corrupted – not, I emphasise, corrupt – because of the different pressures on it and how it has been tweaked over the last 15-20 years, we now have to rebuild it to create a system that is fit for purpose today. That includes national pay scales, central pay setting and limited freedoms. But it gives us a system that we know is fair, we know is adequate in terms of its rewards and is justifiable to the public,” emphasises Paul Whiteman.

“I don’t sense, at the moment, that pay is first on the list of things our members would take to the streets over. School leaders, we all know, are not in it just for their own financial reward. They are truly dedicated to delivering for their children; they care deeply. We’re seeing that the motivation to leave the profession and do something else is accelerating, rather than the desire to disrupt the profession.”

However, in what is potentially something of a warning shot across to the bows that ministers would be wise to heed, Paul adds: “I’m not sure at what point that will switch. However, if things don’t change, I’m confident it will.

“I can’t predict when that will be, but the calls - the calls to do something, the calls for industrial action - are growing louder each time I am in front of members and talking about pay. It’s not loud enough yet to make me think it’s time to agitate, time to organise, but it is catching my attention.”

HILARY GOLDSMITH,

SCHOOL BUSINESS LEADER AT THE JUDD SCHOOL

According to Hilary Goldsmith, school business leader with The Judd School in Tonbridge, Kent and a member of NAHT’s school business leaders’ sector council, the pressures and pinch-points faced by school business leaders are similar, and similarly corrosive, to those experienced by head teachers and other school leaders.

“From the school business leaders’ (SBLs’) side, we need to have an alignment with leadership salaries. This is, first, to attract and, second, to retain school business leaders as part of the senior leadership team. The media and the Department for Education’s communications are all about ‘schools’ and ‘teachers’; they don’t often talk about school leadership. So, school leadership as a ‘thing’, as a concept, has become very blurry,” she told NAHT’s February virtual panel.

As with other school leaders, pay progression was also an issue for SBLs, Hilary pointed out. “The responsibilities that come with school leadership have grown so hugely over the last few years. The gap between an administrator and finance manager, stepping into a truly strategic role and the responsibilities that come with that, is massive but with very little additional recognition,” Hilary added.

STUART SMITH,

HEAD TEACHER AT ST MARY'S PRIMARY SCHOOL

The erosion and stagnation of school leaders’ pay is not just fuelling an exodus at the top; it is becoming a key factor in deterring middle or senior leaders from stepping up to headship or more senior roles, as the ‘Fixing the leadership crisis’ report made clear. Essentially, the intense accountability and workload pressures that come with headship are becoming increasingly unattractive when combined with the fact there is so little extra reward to compensate.

As Stuart Smith, again, highlighted in our panel discussion: “It’s the recruitment of future leaders that, I think, is critical for the sector. When I talk to younger colleagues, I see and hear people who had – and I’m going to use the past tense – aspirations to become head teachers in the future.

“We have potential leaders of the future looking at the sheer range of responsibilities that head teachers have, the accountability that goes with that and the lack of financial incentives. And they don’t see any reason, at this moment in time, to take that final step,” he added.

CLAIRE EVANS,

HEAD TEACHER AT ETON VALLEY PRIMARY SCHOOL

The need for a reformed national pay structure (with mandatory minimum pay points) and pay portability is critical because the narrowing of pay differentials is an important factor in this reluctance to move up. The aspiration for NQTs to have a starting salary of £30,000 simply serves to add insult to the lack of financial progression for people moving into more senior roles.

The impact of a lack of a proper pay continuum or progression was brought into sharp focus in the discussion by Claire Evans, who took on the head teacher role at Eaton Valley Primary School, a two-form entry school in West Bromwich, last September.

“I went from a deputy head in a larger school in Birmingham to Eaton Valley,” she said. “When I was looking for a headship position, it was hard to find something equal to what I was being paid as a deputy. A lot of the two-form entry headships I was looking at would have meant a drop in salary,” she said.

“When I was offered the job here and the grade was lower than what I was on as a deputy, I asked whether they would just match it, and that felt uncomfortable. That leap from deputy to head teacher sometimes is negligible in terms of the pay – none of us does it for the pay, but it would be nice to be rewarded for it,” Claire added.

CHRIS KIRKHAM-KNOWLES,

PRIMARY EXECUTIVE LEADER AT COAST AND VALE LEARNING TRUST

The need for greater codification and definition of executive leadership roles, especially against the backdrop of the academisation and federalisation of the school system, was highlighted by Chris Kirkham-Knowles, the primary executive leader at Coast and Vale Learning Trust in North Yorkshire and chair of NAHT’s professional committee.

“I think heads or senior leaders in small schools face a specific challenge around their pay and remuneration, particularly with the trend towards federation and working across a number of schools. The STPCD isn’t clear about how those people should be remunerated,” he told the panel discussion.

For example, as the head teacher of a small school, you may have a relatively low number of pupils, yet still as much – if not more – responsibility as a head of a larger school, he pointed out. The rollout of multi-academy trusts (MATs), perhaps spread across a number of very different small schools and/or across a wide geographical or rural area (such as, in his area, North Yorkshire), simply amplified the problem.

“It is a very specialised job when it comes to meeting the needs of communities that can differ from one Dale to the next, despite their schools being on each other’s doorsteps. I think there is a particular challenge there in terms of getting it right for school leaders and making sure that people see those roles as attractive ones,” Chris said.

“The clarity of progression is another challenge. The STPCD and the terms and conditions haven’t kept pace with the changes that academisation, federation and other structures have introduced. My job, for example, is one of them. My job isn’t covered by any national negotiation; it has almost been invented as a pay scale. I have no idea where I’d go next if I were looking for career progression. There has been no move towards clarifying any sort of progression,” Chris continued.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

Clearly, there is a compelling argument – and appetite – for change within the profession. But is the government prepared to listen and what happens next, especially if it’s not?

Of course, whether the government is prepared to listen is a question that only the government ultimately can answer. Paul Whiteman, however, emphasises that it is beholden on NAHT and the other teaching unions to at least try to get ministers to hear.

“Our first step has to be reasoned argument with the government. The government has allowed it to get like this; it has to step up now. We have to try to persuade the government that this will be a popular thing to do. Yes, we will get our detractors – but saving education when you, the government, have placed education, correctly, in the centre of the country’s recovery involves making sure you look after those leading it,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“We also have to persuade the STRB to have the confidence of its mission and to stand up and say what’s in front of its face. Don’t, for example, be guided by the government to say, ‘within the bounds of affordability’. Simply state (based on the evidence it receives) what the pay rate should be.

“I think, within this, we need to be having quite an in-depth conversation with the STRB and the government about pay system reform within education. It is a frightening prospect for some, I recognise; the idea of having a conversation around national pay scales, local pay systems, pay freedoms and all the rest of it,” Paul continues.

As to the second ‘what happens next?’ question, there are two strands: the technical, practical process and then a wider, more existential conversation.

The technical, practical process is straightforward enough. The report has now gone to the STRB. There follows a period to submit supplementary evidence. After which, NAHT will give oral evidence to the STRB, which then submits its recommendations to the secretary of state, who is the decision-maker.

Once again, the timeframe is running seriously behind this year, so the deadlines are extremely tight. Theoretically, an announcement on pay should be made before September, but this is likely to run late again – perhaps even into December, says Ian Hartwright.

As to the second strand – what NAHT and the profession can or should do in response to an intransigent or simply belligerent government – that is, naturally, more challenging. Are we hurtling, irrevocably, towards a fracturing of relations and, even, the prospect of industrial action if things don’t improve or if the warnings of the profession are not heeded?

“For me, as the system has become corrupted – not, I emphasise, corrupt – because of the different pressures on it and how it has been tweaked over the last 15-20 years, we now have to rebuild it to create a system that is fit for purpose today. That includes national pay scales, central pay setting and limited freedoms. But it gives us a system that we know is fair, we know is adequate in terms of its rewards and is justifiable to the public,” emphasises Paul Whiteman.

“I don’t sense, at the moment, that pay is first on the list of things our members would take to the streets over. School leaders, we all know, are not in it just for their own financial reward. They are truly dedicated to delivering for their children; they care deeply. We’re seeing that the motivation to leave the profession and do something else is accelerating, rather than the desire to disrupt the profession.”

However, in what is potentially something of a warning shot across to the bows that ministers would be wise to heed, Paul adds: “I’m not sure at what point that will switch. However, if things don’t change, I’m confident it will.

“I can’t predict when that will be, but the calls - the calls to do something, the calls for industrial action - are growing louder each time I am in front of members and talking about pay. It’s not loud enough yet to make me think it’s time to agitate, time to organise, but it is catching my attention.”

VIEW FROM THE NATIONS

LAURA DOEL,

NAHT CYMRU DIRECTOR

NAHT Cymru is submitting a response to the Independent Welsh Pay Review Body (IWPRB) and has been surveying its members on pay and well-being, highlights NAHT Cymru director Laura Doel.

“And we are still seeing the differentials between leadership pay and the main pay scale being narrowed, which is a real concern when it comes to progression. When you combine it with workload pressures and significant leadership responsibility, you have people saying, ‘I’m better off staying where I am’.

“We are calling for a significant pay rise. We are also in conversations with the Welsh Government to set a three-year or longer fully-funded pay deal, rather than year-on-year pay settlements where the budgetary pressure is also pushed back on to schools by local authorities,” Laura adds.

With it now a legal requirement for schools to have an additional learning needs coordinator (ALNCo) in place, there are ongoing issues around remuneration and the fact there is no defined pay structure for this role.

“We are calling for a pay scale for ALNCos that recognises their role and responsibility. We are looking, too, at remuneration for school leaders responsible for more than one school,” Laura highlights.

“We have a growing trend of federations of schools, and we don’t have a mechanism by which to pay them. Pay for school leaders responsible for more than one school is still calculated on pupil numbers. But this may not reflect the responsibility of, say, managing a federation of small, rural, community schools.

“You might have just 120 pupils between three schools, for example, but you are managing three lots of teams, three sites and all of the management responsibility that goes with that. A school leader down the road might have 200 pupils in just one school, and they’re getting paid more. So, we are pushing for the Welsh Government to look at that. It has been included as a point of discussion for the IWPRB, and we have been gathering evidence,” Laura adds.

GRAHAM GAULT,

NAHT(NI) INTERIM DIRECTOR

In Northern Ireland, after unions jointly put in a claim for 6%, school leaders and head teachers have now been offered an increase of 2.49% over two years.

“It is even worse than just the headline figure because the way the employers have decided to make this increase is by adjusting the leadership pay scale,” highlights NAHT Northern Ireland interim director Graham Gault.

“So, for each band that our members might be on, they have taken off the bottom one and put another point on the top. That means while the band as a whole may have an increase of 2.49% – it is, of course, nowhere near even the current rate of inflation – the only person who can benefit from that in the short term is the member who is on the upper end of that scale because they now have a new point to go to.

“The pay offer is an insult to our members. It is a very poor offer,” Graham adds.

The dissatisfaction has been such that a ballot was held during February on whether to accept the offer, with NAHT members in Northern Ireland voting to reject it. Indeed, all five trade unions in the collective bargaining group, known as the Northern Ireland Teachers’ Council (NITC), have now formally rejected the offer. Given the current wider political paralysis in Northern Ireland, how this is all going to be resolved remains uncertain.

“The other complication within all this is, with the collapse of the Northern Ireland Executive, the difficulty now of getting back to the negotiating table,” Graham highlights.

VIEW FROM THE NATIONS

LAURA DOEL,

NAHT CYMRU DIRECTOR

NAHT Cymru is submitting a response to the Independent Welsh Pay Review Body (IWPRB) and has been surveying its members on pay and well-being, highlights NAHT Cymru director Laura Doel.

“And we are still seeing the differentials between leadership pay and the main pay scale being narrowed, which is a real concern when it comes to progression. When you combine it with workload pressures and significant leadership responsibility, you have people saying, ‘I’m better off staying where I am’.

“We are calling for a significant pay rise. We are also in conversations with the Welsh Government to set a three-year or longer fully-funded pay deal, rather than year-on-year pay settlements where the budgetary pressure is also pushed back on to schools by local authorities,” Laura adds.

With it now a legal requirement for schools to have an additional learning needs coordinator (ALNCo) in place, there are ongoing issues around remuneration and the fact there is no defined pay structure for this role.

“We are calling for a pay scale for ALNCos that recognises their role and responsibility. We are looking, too, at remuneration for school leaders responsible for more than one school,” Laura highlights.

“We have a growing trend of federations of schools, and we don’t have a mechanism by which to pay them. Pay for school leaders responsible for more than one school is still calculated on pupil numbers. But this may not reflect the responsibility of, say, managing a federation of small, rural, community schools.

“You might have just 120 pupils between three schools, for example, but you are managing three lots of teams, three sites and all of the management responsibility that goes with that. A school leader down the road might have 200 pupils in just one school, and they’re getting paid more. So, we are pushing for the Welsh Government to look at that. It has been included as a point of discussion for the IWPRB, and we have been gathering evidence,” Laura adds.

GRAHAM GAULT,

NAHT(NI) INTERIM DIRECTOR

In Northern Ireland, after unions jointly put in a claim for 6%, school leaders and head teachers have now been offered an increase of 2.49% over two years.

“It is even worse than just the headline figure because the way the employers have decided to make this increase is by adjusting the leadership pay scale,” highlights NAHT Northern Ireland interim director Graham Gault.

“So, for each band that our members might be on, they have taken off the bottom one and put another point on the top. That means while the band as a whole may have an increase of 2.49% – it is, of course, nowhere near even the current rate of inflation – the only person who can benefit from that in the short term is the member who is on the upper end of that scale because they now have a new point to go to.

“The pay offer is an insult to our members. It is a very poor offer,” Graham adds.

The dissatisfaction has been such that a ballot was held during February on whether to accept the offer, with NAHT members in Northern Ireland voting to reject it. Indeed, all five trade unions in the collective bargaining group, known as the Northern Ireland Teachers’ Council (NITC), have now formally rejected the offer. Given the current wider political paralysis in Northern Ireland, how this is all going to be resolved remains uncertain.

“The other complication within all this is, with the collapse of the Northern Ireland Executive, the difficulty now of getting back to the negotiating table,” Graham highlights.

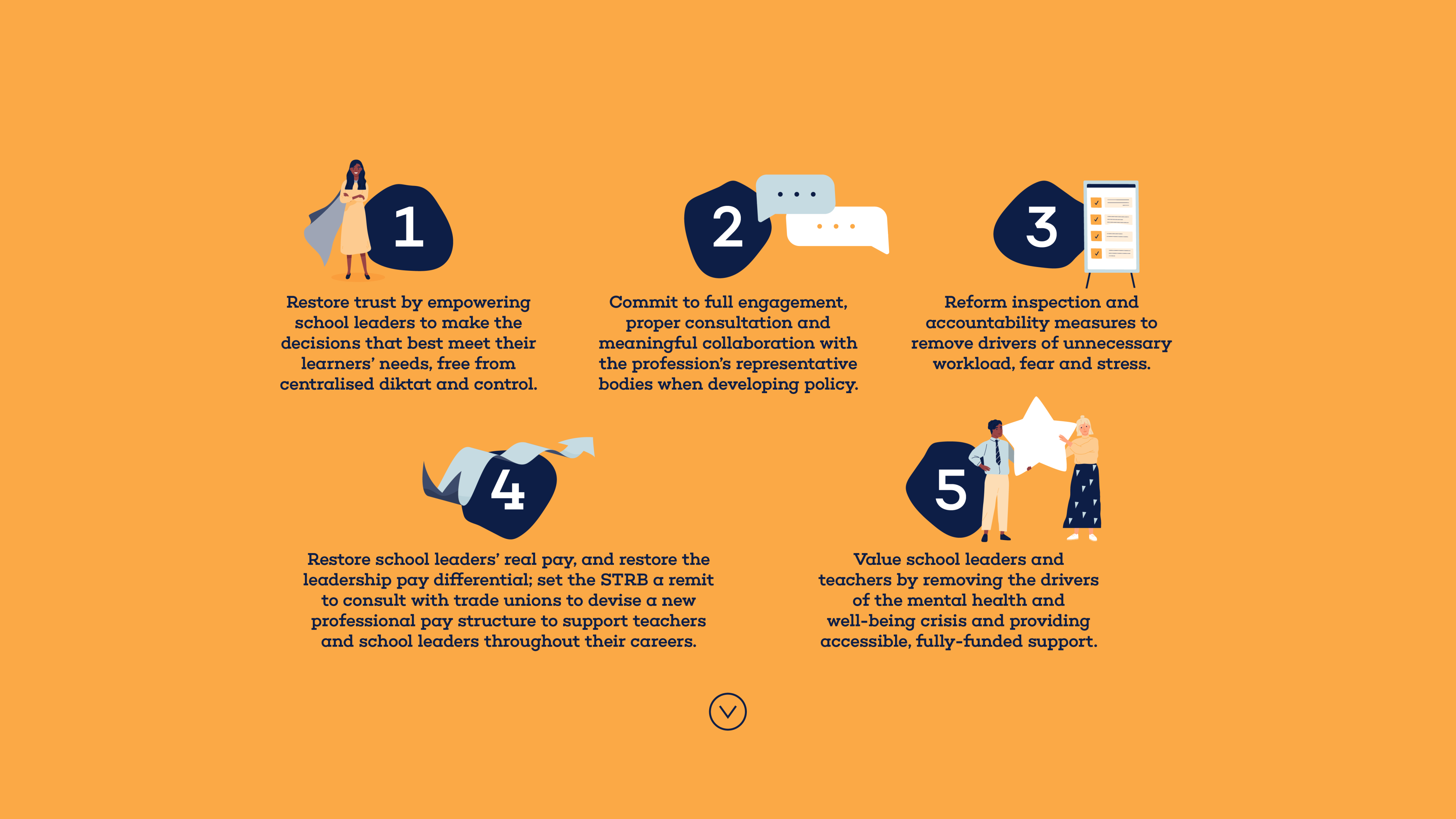

WHAT NAHT HAS SAID

In the ‘Fixing the leadership crisis’ report, NAHT made it very clear change is needed to resolve the growing recruitment and retention crisis and for school leadership to become a sustainable career.

Indeed, the report has argued that it is ‘essential’ school leaders feel able, eager and willing to commit to decades-long careers.

The report concluded the following:

The report argued that ‘urgent and coordinated action’ was now required to ensure a sufficient pipeline of school leaders for the future.

It made five key recommendations to the government.

The grim picture for school leaders and head teachers was mimicked in NAHT’s other report, ‘School business leadership in crisis? Making school business leadership sustainable’.

This report concluded that the number of school business leaders who would recommend school leadership fell by 10% between 2020 and 2021, from 48% to 43%.

As for other school leaders, the pressures on school business leaders were driving worrying mental health and well-being outcomes, with 70% reporting increased worry, fear or stress about their job, an increase of 30% in the last year alone.

Three quarters (75%) of respondents disagreed that their salary fairly reflects the roles and responsibilities they undertake. Equally worrying, almost a fifth (19%) of respondents said they planned to leave within the next year.

As with the ‘Fixing the leadership crisis’ report, ‘urgent and coordinated action’ was required to ensure the sufficient supply of school business leaders for now and in the future, NAHT argued. It urged the government to develop ‘a comprehensive and holistic strategy’ to support the pipeline of school business leaders.

This strategy needed to:

• Include initiatives to tackle the workload of school business leaders, integrated with those offered for the leadership profession as a whole

• Resolve the issues around the disparity in pay many school business leaders face by ensuring that school business leaders performing a leadership level role are able to be paid at an equivalent level to other comparable leadership roles

• To support this, NAHT is calling for a thorough review of the leadership pay structure, which should include aligning the pay of school business leaders alongside a revised STPCD

• Raise the professional status of school business leaders within the sector and schools. This should include working with the sector to develop materials and guidance on how schools can embed and maximise the impact of school business leaders in their staffing structure

• Provide greater support to help mitigate some of the systemic barriers to flexible working opportunities for all roles, including school business leaders

• Remove the drivers of the mental health and well-being crisis, and provide accessible, fully-funded support for school business leaders.

This strategy needed to:

• Include initiatives to tackle the workload of school business leaders, integrated with those offered for the leadership profession as a whole

• Resolve the issues around the disparity in pay many school business leaders face by ensuring that school business leaders performing a leadership level role are able to be paid at an equivalent level to other comparable leadership roles

• To support this, NAHT is calling for a thorough review of the leadership pay structure, which should include aligning the pay of school business leaders alongside a revised STPCD

• Raise the professional status of school business leaders within the sector and schools. This should include working with the sector to develop materials and guidance on how schools can embed and maximise the impact of school business leaders in their staffing structure

• Provide greater support to help mitigate some of the systemic barriers to flexible working opportunities for all roles, including school business leaders

• Remove the drivers of the mental health and well-being crisis, and provide accessible, fully-funded support for school business leaders.