How are your

health and well-being?

Leadership Focus journalist Nic Paton looks at how the pressures of leading through a pandemic have taken their toll.

Head teachers and school leaders are used to the argument that their role is more about the vocation than the money, and they don’t expect much in the way of plaudits from politicians (unlikely anyway from the current government) or even the public.

It’s true that you go above and beyond for the children, for the life-changing benefit and agency you can bring to young people’s futures, and for the positive mark your actions and decisions will leave on your local area. But that is not a reason to pay you poorly or for the government to neglect your well-being. It is not wrong for a school leader to expect, even demand, to be as well remunerated and treated like any other professional graduate occupation.

The pivotal role of schools and school leaders in shaping, supporting and serving their local communities has, of course, been highlighted like never before over the past two years of the covid-19 pandemic. But at what personal cost?

NAHT’s recent report, ‘Fixing the leadership crisis: time for change’, highlighted how a decade of erosion of pay and recognition and of unsustainable workload and high-stakes accountability – together with the intense pressures of leading through a pandemic – is all taking a terrible toll on head teachers’ and school leaders’ health and well-being.

The report also identified a growing need for mental health and well-being support across all school job roles. More than a quarter (27%) of school leaders said supporting staff members’ well-being was one of the top three greatest impacts on their workload over the last year.

The vast majority (91%) of assistant and deputy heads reported that the mental health support they provide to staff had increased or ‘greatly’ increased over the last three years. More than a third (35%) of middle leaders and 38% of assistant and deputy heads said they had identified a personal need for mental health or well-being support during the past year.

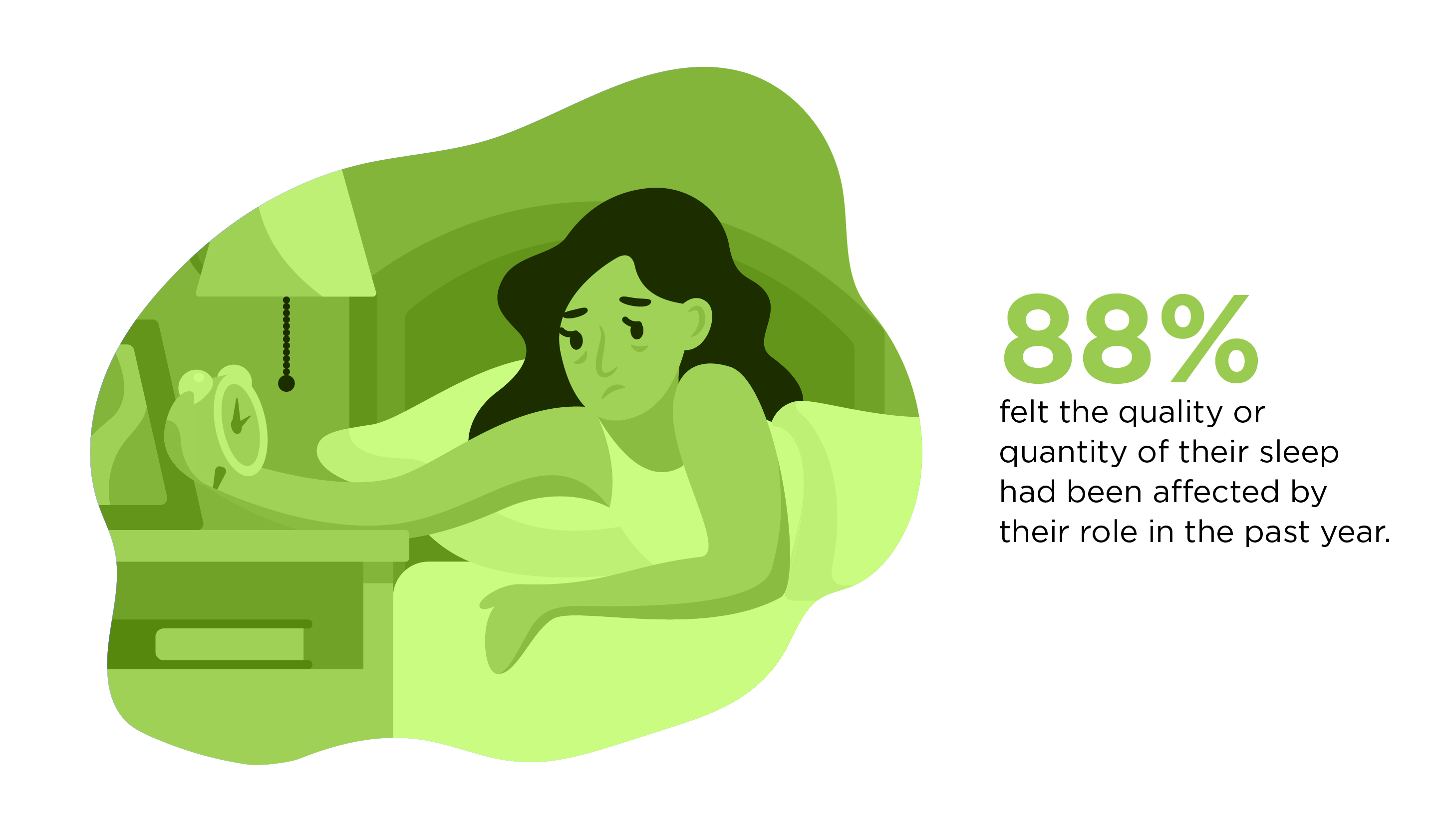

Almost all – nine in ten, or 88% – felt the quality or quantity of their sleep had been affected by their role in the past year, increasing from 83% in 2020. A total of 83% of respondents reported increased worry, fear or stress about their job, an increase of more than 15% over the last year. Almost six in ten (59%) said their role has had a negative impact on their physical health, compared with 46% in 2020.

These deeply concerning conclusions prompted NAHT to gather members together in February to gauge just how ‘sick’ school leadership is becoming and what, if anything, can be done about it.

The report also identified a growing need for mental health and well-being support across all school job roles. More than a quarter (27%) of school leaders said supporting staff members’ well-being was one of the top three greatest impacts on their workload over the last year.

The vast majority (91%) of assistant and deputy heads reported that the mental health support they provide to staff had increased or ‘greatly’ increased over the last three years. More than a third (35%) of middle leaders and 38% of assistant and deputy heads said they had identified a personal need for mental health or well-being support during the past year.

Almost all – nine in ten, or 88% – felt the quality or quantity of their sleep had been affected by their role in the past year, increasing from 83% in 2020. A total of 83% of respondents reported increased worry, fear or stress about their job, an increase of more than 15% over the last year. Almost six in ten (59%) said their role has had a negative impact on their physical health, compared with 46% in 2020.

These deeply concerning conclusions prompted NAHT to gather members together in February to gauge just how ‘sick’ school leadership is becoming and what, if anything, can be done about it.

IT DIDN'T TAKE LONG TO FIND OUT

Within minutes of the virtual event starting – in fact still during the opening ‘introductions’ – NAHT members were pouring out the mental and physical toll that the past two years of managing and leading during the pandemic had taken on them, in something almost akin to a cathartic ‘therapy session’.

Members talked about how Ofsted restarting inspections added to an already unsustainable situation; they spoke about the impact their roles had had on their mental and physical health, including feelings of burnout, guilt, desperation, anxiety and comfort eating.

Deeply worrying, every NAHT member in the discussion indicated they were either now actively looking at taking early retirement – as early as financially possible – or planning to leave the profession early.

The fear, therefore, is that members’ experience of the pandemic risks turning the ‘leaky pipeline’ of school leaders’ recruitment and retention identified by NAHT back in 2017 into a full-blown, gushing torrent of a leadership crisis in the not-too-distant future.

NAHT has made it very clear in its latest evidence on pay to the independent School Teachers’ Review Body (discussed in more detail elsewhere) that, alongside pay in members’ pockets, a deeper conversation is needed around how school leadership (and teaching more widely) can become a more sustainable and sustaining career.

As it has said: “The situation is not irretrievable, but the window in which to act is closing quickly. If the pandemic lifts, long-delayed career decisions are likely to come into play across all job roles. The evidence strongly demonstrates that morale and aspiration are at an all-time low. Truly terrible mental health and well-being indicators make teaching look a desperately unattractive profession to join.”

IAN HARTWRIGHT,

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISOR

For Ian Hartwright, NAHT senior policy advisor, the findings from the ‘Fixing the leadership crisis’ report should be ringing massive alarm bells in government.

“This is a blindingly important wake-up call for the government. A third of our assistant, deputy and middle leadership members have said they had a mental health or well-being need – and had identified that in the last year. There will be many more people, I suspect, who won’t have quite identified that for themselves.

“It is very doubled-edged. If a third of your workforce is telling you that their work is making them ill, the government really does need to sit up and take notice of that,” Ian tells Leadership Focus.

IT DIDN'T TAKE LONG TO FIND OUT

Within minutes of the virtual event starting – in fact still during the opening ‘introductions’ – NAHT members were pouring out the mental and physical toll that the past two years of managing and leading during the pandemic had taken on them, in something almost akin to a cathartic ‘therapy session’.

Members talked about how Ofsted restarting inspections added to an already unsustainable situation; they spoke about the impact their roles had had on their mental and physical health, including feelings of burnout, guilt, desperation, anxiety and comfort eating.

Deeply worrying, every NAHT member in the discussion indicated they were either now actively looking at taking early retirement – as early as financially possible – or planning to leave the profession early.

The fear, therefore, is that members’ experience of the pandemic risks turning the ‘leaky pipeline’ of school leaders’ recruitment and retention identified by NAHT back in 2017 into a full-blown, gushing torrent of a leadership crisis in the not-too-distant future.

NAHT has made it very clear in its latest evidence on pay to the independent School Teachers’ Review Body (discussed in more detail elsewhere) that, alongside pay in members’ pockets, a deeper conversation is needed around how school leadership (and teaching more widely) can become a more sustainable and sustaining career.

As it has said: “The situation is not irretrievable, but the window in which to act is closing quickly. If the pandemic lifts, long-delayed career decisions are likely to come into play across all job roles. The evidence strongly demonstrates that morale and aspiration are at an all-time low. Truly terrible mental health and well-being indicators make teaching look a desperately unattractive profession to join.”

IAN HARTWRIGHT,

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISOR

For Ian Hartwright, NAHT senior policy advisor, the findings from the ‘Fixing the leadership crisis’ report should be ringing massive alarm bells in government.

“This is a blindingly important wake-up call for the government. A third of our assistant, deputy and middle leadership members have said they had a mental health or well-being need – and had identified that in the last year. There will be many more people, I suspect, who won’t have quite identified that for themselves.

“It is very doubled-edged. If a third of your workforce is telling you that their work is making them ill, the government really does need to sit up and take notice of that,” Ian tells Leadership Focus.

WHAT, THEN, CAN BE DONE?

Clearly, making school leadership a more sustainable and viable long-term career (and, crucially, one that is not going to make you ill) is not something that can happen overnight.

As one head teacher on the panel pointed out, it was the spiralling burden of workload combined with the pressure of high-stakes accountability, with a lack of pay, recognition and respect, and with the scouring effects of the pandemic that were all coming together to create a toxic mix. For example, he and his wife (a teacher) had experienced 12 Ofsted inspections within their first 10 years of married life.

Even for those head teachers who have been resilient enough to survive decades at the top of the profession, the experience of the pandemic has tipped many of them over the edge.

One Essex head teacher, a head for nearly two decades, told how the exit to retirement now can’t come soon enough.

“I’ve met with the pensions adviser. I am past 50 years of age; I will be hitting 55 and then running. My husband is also a teacher. He is also planning to leave when I’m 55; his comment was: ‘I could go and work in Tesco and not have to bring work home in the evening.’ There is, I feel, going to be a huge leadership crisis,” she said.

A further factor – and worry – highlighted by the panel was the additional financial burden on already stretched school budgets of affording all the extra mental health and well-being support and assistance that, increasingly, was now needed.

One panellist pointed out that in her school, they fund a counsellor to come in once a fortnight for an afternoon, usually to do three hours at the cost of £50 an hour, with staff able to self-refer for support. Senior leaders had access to mental health training, and the school had paid for staff members to gain mental health first-aider qualifications.

“Mental health support is very useful, particularly for members of staff who we know have mental health needs or when staff are in crisis,” she explained. “But, looking at our budget, it may be something we need to reduce because we can’t afford to continue paying it. And the staff do know they are very lucky to receive that.

“Because of the volume of people who want to see the counsellor, they don’t get regular support. We book a session for the senior leadership team to do a supervision session, but that is only once a term. But if you are in crisis as a leader, you should not have to wait until the next term for time to book a slot with a counsellor to talk about the crisis you had six weeks ago,” she added.

A further panellist highlighted how, too often, community or NHS mental health services are inaccessible or unavailable, both for children and adults. Yet, buying occupational health support is an expensive option for many schools when budgets are tight.

“CAMHS (NHS Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services) is so broken in this area; if you have a suicidal child, it can take about two years to get them support. And it is the same for adult mental health support. It comes down to funding,” he said.

Another pointed to the fact there is still often a stigma around accessing mental health support – about feeling that, by asking for help, you are somehow ‘failing’ as a school leader.

“I think there is an educational aspect to this for school leaders as well. I think we need a level of support and supervision similar to, say, what a GP might expect or be offered – again, a very stressful occupation. Any professional occupational usually has expectations of supervision,” he said.

“The problem is we all manage large numbers of staff. We refer some to occupational health for mental health support. As school leaders and managers, we often utilise these services to support our staff, but this is something that should be built in to our profession so that it is an expectation of having supervision and support.

“If it was actually supervision as opposed to ‘mental health’, I think you would get a lot more buy-in by the professionals who are leaders in schools,” he added.

Ultimately, as another panellist expressed strongly, supporting head teachers’ and school leaders’ well-being needs comes back to three words: support, recognition and status.

As he put it, in a powerful call to the government: “Support us to do the job you want us to do by investing in us and giving us the tools to do the job. Recognise that we are doing our very, very best. And be public about it. Don’t imply it, and don’t be mealy-mouthed.

“Get behind us and say, ‘school leaders do an amazing job’ all the time; when parents question that, stand behind school leadership and say, ‘trust the leaders in your schools to solve your children’s problems for you’.”

WHAT, THEN, CAN BE DONE?

Clearly, making school leadership a more sustainable and viable long-term career (and, crucially, one that is not going to make you ill) is not something that can happen overnight.

As one head teacher on the panel pointed out, it was the spiralling burden of workload combined with the pressure of high-stakes accountability, with a lack of pay, recognition and respect, and with the scouring effects of the pandemic that were all coming together to create a toxic mix. For example, he and his wife (a teacher) had experienced 12 Ofsted inspections within their first 10 years of married life.

Even for those head teachers who have been resilient enough to survive decades at the top of the profession, the experience of the pandemic has tipped many of them over the edge.

One Essex head teacher, a head for nearly two decades, told how the exit to retirement now can’t come soon enough.

“I’ve met with the pensions adviser. I am past 50 years of age; I will be hitting 55 and then running. My husband is also a teacher. He is also planning to leave when I’m 55; his comment was: ‘I could go and work in Tesco and not have to bring work home in the evening.’ There is, I feel, going to be a huge leadership crisis,” she said.

A further factor – and worry – highlighted by the panel was the additional financial burden on already stretched school budgets of affording all the extra mental health and well-being support and assistance that, increasingly, was now needed.

One panellist pointed out that in her school, they fund a counsellor to come in once a fortnight for an afternoon, usually to do three hours at the cost of £50 an hour, with staff able to self-refer for support. Senior leaders had access to mental health training, and the school had paid for staff members to gain mental health first-aider qualifications.

“Mental health support is very useful, particularly for members of staff who we know have mental health needs or when staff are in crisis,” she explained. “But, looking at our budget, it may be something we need to reduce because we can’t afford to continue paying it. And the staff do know they are very lucky to receive that.

“Because of the volume of people who want to see the counsellor, they don’t get regular support. We book a session for the senior leadership team to do a supervision session, but that is only once a term. But if you are in crisis as a leader, you should not have to wait until the next term for time to book a slot with a counsellor to talk about the crisis you had six weeks ago,” she added.

A further panellist highlighted how, too often, community or NHS mental health services are inaccessible or unavailable, both for children and adults. Yet, buying occupational health support is an expensive option for many schools when budgets are tight.

“CAMHS (NHS Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services) is so broken in this area; if you have a suicidal child, it can take about two years to get them support. And it is the same for adult mental health support. It comes down to funding,” he said.

Another pointed to the fact there is still often a stigma around accessing mental health support – about feeling that, by asking for help, you are somehow ‘failing’ as a school leader.

“I think there is an educational aspect to this for school leaders as well. I think we need a level of support and supervision similar to, say, what a GP might expect or be offered – again, a very stressful occupation. Any professional occupational usually has expectations of supervision,” he said.

“The problem is we all manage large numbers of staff. We refer some to occupational health for mental health support. As school leaders and managers, we often utilise these services to support our staff, but this is something that should be built in to our profession so that it is an expectation of having supervision and support.

“If it was actually supervision as opposed to ‘mental health’, I think you would get a lot more buy-in by the professionals who are leaders in schools,” he added.

Ultimately, as another panellist expressed strongly, supporting head teachers’ and school leaders’ well-being needs comes back to three words: support, recognition and status.

As he put it, in a powerful call to the government: “Support us to do the job you want us to do by investing in us and giving us the tools to do the job. Recognise that we are doing our very, very best. And be public about it. Don’t imply it, and don’t be mealy-mouthed.

“Get behind us and say, ‘school leaders do an amazing job’ all the time; when parents question that, stand behind school leadership and say, ‘trust the leaders in your schools to solve your children’s problems for you’.”

HOW NAHT WORKS TO SUPPORT YOUR HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

For members who feel they are struggling, whether mentally or physically, NAHT offers a range of well-being support resources, which you can access here: www.naht.org.uk/well-being

This support includes access to confidential counselling, expert advisors, financial well-being assistance and much, much more.

TIM BOWEN,

NAHT PRESIDENT

Furthermore, NAHT president Tim Bowen has made health and well-being a key priority for his year as president.

He has nominated Education Support, which has been supporting NAHT members for a number of years, as his charity for the year.

You can find out more about

Education Support and what it offers.

For members who feel they are struggling, whether mentally or physically, NAHT offers a range of well-being support resources, which you can access here: www.naht.org.uk/well-being

This support includes access to confidential counselling, expert advisors, financial well-being assistance and much, much more.

TIM BOWEN,

NAHT PRESIDENT

Furthermore, NAHT president Tim Bowen has made health and well-being a key priority for his year as president.

He has nominated Education Support, which has been supporting NAHT members for a number of years, as his charity for the year.

You can find out more about

Education Support and what it offers.

I’ve watched members age before my eyes over the pandemic. It was tough before, but the last two years have brought into sharp focus just the level of pressure that school leadership is under, writes NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

Members have abused their health – both mentally and physically – to keep the show on the road. You can see it in their faces. Even before they begin to describe the impact it’s had on their personal life or health, you can see people physically changing. I have heard harrowing stories of members who have had to visit the doctor for acute stress-related problems, but also of members who have put off seeing a doctor because of their dedication to the task.

We’re only just beginning to understand the depth of the toll this has had on members.

If the government doesn’t begin to listen to the profession about the impact the pandemic is having on the health and well-being of school leaders, combined with general workload and accountability pressures and the ongoing lack of recognition, we’re just going to fall further and further into crisis.

What is beginning to worry me is the number of members who are now asking for quotes for their pensions. A while ago, we surveyed members asking how many had thought of leaving the profession earlier than the normal retirement age. Nearly half, 47%, said they wanted to go after the pandemic.

To me, that says a couple of things. First, just the sheer professionalism of people who are beyond frustration – that they will not leave their school in the middle of a crisis.

We know that survey data of people’s intentions doesn’t always follow through to actions later. But we are experiencing a spike in calls, with members saying, ‘I want to retire, so please can you give me some advice?’. How that translates to how many we lose, we have yet to see.

But the signals are that people are truly beginning to prepare to go. The risk is we will lose a load of leadership and teaching experience, which weakens education.

I’ve watched members age before my eyes over the pandemic. It was tough before, but the last two years have brought into sharp focus just the level of pressure that school leadership is under, writes NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

Members have abused their health – both mentally and physically – to keep the show on the road. You can see it in their faces. Even before they begin to describe the impact it’s had on their personal life or health, you can see people physically changing. I have heard harrowing stories of members who have had to visit the doctor for acute stress-related problems, but also of members who have put off seeing a doctor because of their dedication to the task.

We’re only just beginning to understand the depth of the toll this has had on members.

If the government doesn’t begin to listen to the profession about the impact the pandemic is having on the health and well-being of school leaders, combined with general workload and accountability pressures and the ongoing lack of recognition, we’re just going to fall further and further into crisis.

What is beginning to worry me is the number of members who are now asking for quotes for their pensions. A while ago, we surveyed members asking how many had thought of leaving the profession earlier than the normal retirement age. Nearly half, 47%, said they wanted to go after the pandemic.

To me, that says a couple of things. First, just the sheer professionalism of people who are beyond frustration – that they will not leave their school in the middle of a crisis.

We know that survey data of people’s intentions doesn’t always follow through to actions later. But we are experiencing a spike in calls, with members saying, ‘I want to retire, so please can you give me some advice?’. How that translates to how many we lose, we have yet to see.

But the signals are that people are truly beginning to prepare to go. The risk is we will lose a load of leadership and teaching experience, which weakens education.

VIEW FROM THE NATIONS

THE VIEW FROM WALES

LAURA DOEL,

NAHT CYMRU DIRECTOR

On top of the general pressures of managing and leading through a pandemic, Welsh school leaders and head teachers face a number of extra pressure points, highlights NAHT Cymru director Laura Doel. First, there is the rollout of the new curriculum for Wales, which will be up and running from this September.

Second, new legislation has been put in place for additional learning needs (ALN) in Wales, meaning it has become a legal requirement for every school to have an ALN coordinator and carry out a review of pupils’ needs and offer support where necessary.

Third, as in England, there is the pressure of Estyn's inspection arrangements, compounded by a new inspection regime being introduced in pilot form from the spring. On top of all this, the Welsh Government is looking at reforming the school day and school year, potentially extending the school day and making changes to the school holidays. Read our policy update on page 41 of the print version of Leadership Focus for more on this.

“So, we are at a very stressful point in Wales,” says Laura. “Even before the pandemic, we were concerned about the curriculum rollout. It involves such a significant change in terms of what's expected of practice and pedagogy, and it requires a cultural shift too. Practitioners grew up in the national curriculum – went to school with the national curriculum and have only ever taught the national curriculum – and now the rule book is being ripped up.

“People will have the freedom to develop a curriculum that suits their setting and learners, so on the one hand (and positively), it does allow for innovation; it is something that has really driven enthusiasm among practitioners in Wales. However, on the other, it’s not easy to do. The support and training offered to members have also been a mixed picture,” Laura adds.

“I think it is fair to say our members are feeling the pressure. That’s not to say they don’t continue to step up every day they walk into school and lead their teams with a smile on their face – because they do very much. But behind that, in the privacy of their offices, I know from my conversations with members, there is a real concern along the lines of ‘how much longer can we keep going?’, ‘how can we continue to work at this level?’ and about what is coming round the corner.

“With every month that goes by, there seems to be something else. Rather than things easing, additional pressures seem to be coming to the fore, which is really having an effect.

“We’re already struggling with recruitment and retention in Wales as much as in England. There are challenges in Wales, especially in border local authority areas. For example, you can see a border drain issue if terms and conditions or pay is favourable in a neighbouring school in an English local authority.

“We have people who are very early on in a leadership career saying, ‘no, this is not for me’. Or people who have come into middle leadership saying, ‘no way’ to additional responsibility,” Laura adds.

THE VIEW FROM NORTHERN IRELAND

GRAHAM GAULT,

NAHT(NI) INTERIM DIRECTOR

Much as in England, in Northern Ireland, the combination of workload, the pandemic, accountability pressures and a general lack of recognition and remuneration is creating real fear of a looming retirement and retention crisis, says NAHT Northern Ireland interim director Graham Gault.

“We ran a retirement seminar for members a few weeks ago, and I was shocked that more than 10% of our total membership turned up. That really surprised me; it frightened me. Some people will have just been there for information, of course, but we might need a big recruitment drive in the years to come,” he warns.

Graham is himself chair of a working party reviewing school leaders’ workload. While this has yet to report, he suggests the evidence gathered so far is seriously worrying.

“The issue of pay came up within the evidence sessions, from principals from all sectors,” Graham points out. “It wasn’t that the principals wanted more money. There were two factors that I could identify. The first was a feeling of a complete lack of respect and value; it is just so damaging to morale – the feeling that you don’t count.

“School leaders’ pay is not bad when you compare it with the public sector. But whenever you sit down and look at what they do – in Northern Ireland, there is a completely open-ended contractual situation. That means everything and anything can end up falling to the principal every time,” he says.

“The second factor that members raised, again and again, is that in Northern Ireland, principals and vice-principals, people in leadership roles, don’t have access to any other form of remuneration or recompense for additional responsibilities.

“So, for example, if you’re a teacher and take on the role of special needs coordinator, you will get one or two teaching allowances for that. What we’ve seen over the past decade is school leaders increasingly taking on these really big roles, first, to save finances for the school and, second, because quite often, teachers just don’t want to do them. But whenever a principal or vice-principal takes on this role, there is no recompense for them; they aren’t entitled to any additional allowances.

“People are just at the end of their tether. Incoming calls to the office about health concerns are up. Incoming calls to the office about retirement and looking at options for leaving the profession are up. Even just anecdotally, there is such a sense of desolation out there; it is really awful,” Graham adds.

THE VIEW FROM WALES

LAURA DOEL,

NAHT CYMRU DIRECTOR

On top of the general pressures of managing and leading through a pandemic, Welsh school leaders and head teachers face a number of extra pressure points, highlights NAHT Cymru director Laura Doel. First, there is the rollout of the new curriculum for Wales, which will be up and running from this September.

Second, new legislation has been put in place for additional learning needs (ALN) in Wales, meaning it has become a legal requirement for every school to have an ALN coordinator and carry out a review of pupils’ needs and offer support where necessary.

Third, as in England, there is the pressure of Estyn's inspection arrangements, compounded by a new inspection regime being introduced in pilot form from the spring. On top of all this, the Welsh Government is looking at reforming the school day and school year, potentially extending the school day and making changes to the school holidays. Read our policy update on page 41 of the print version of Leadership Focus for more on this.

“So, we are at a very stressful point in Wales,” says Laura. “Even before the pandemic, we were concerned about the curriculum rollout. It involves such a significant change in terms of what's expected of practice and pedagogy, and it requires a cultural shift too. Practitioners grew up in the national curriculum – went to school with the national curriculum and have only ever taught the national curriculum – and now the rule book is being ripped up.

“People will have the freedom to develop a curriculum that suits their setting and learners, so on the one hand (and positively), it does allow for innovation; it is something that has really driven enthusiasm among practitioners in Wales. However, on the other, it’s not easy to do. The support and training offered to members have also been a mixed picture,” Laura adds.

“I think it is fair to say our members are feeling the pressure. That’s not to say they don’t continue to step up every day they walk into school and lead their teams with a smile on their face – because they do very much. But behind that, in the privacy of their offices, I know from my conversations with members, there is a real concern along the lines of ‘how much longer can we keep going?’, ‘how can we continue to work at this level?’ and about what is coming round the corner.

“With every month that goes by, there seems to be something else. Rather than things easing, additional pressures seem to be coming to the fore, which is really having an effect.

“We’re already struggling with recruitment and retention in Wales as much as in England. There are challenges in Wales, especially in border local authority areas. For example, you can see a border drain issue if terms and conditions or pay is favourable in a neighbouring school in an English local authority.

“We have people who are very early on in a leadership career saying, ‘no, this is not for me’. Or people who have come into middle leadership saying, ‘no way’ to additional responsibility,” Laura adds.

THE VIEW FROM NORTHERN IRELAND

GRAHAM GAULT,

NAHT(NI) INTERIM DIRECTOR

Much as in England, in Northern Ireland, the combination of workload, the pandemic, accountability pressures and a general lack of recognition and remuneration is creating real fear of a looming retirement and retention crisis, says NAHT Northern Ireland interim director Graham Gault.

“We ran a retirement seminar for members a few weeks ago, and I was shocked that more than 10% of our total membership turned up. That really surprised me; it frightened me. Some people will have just been there for information, of course, but we might need a big recruitment drive in the years to come,” he warns.

Graham is himself chair of a working party reviewing school leaders’ workload. While this has yet to report, he suggests the evidence gathered so far is seriously worrying.

“The issue of pay came up within the evidence sessions, from principals from all sectors,” Graham points out. “It wasn’t that the principals wanted more money. There were two factors that I could identify. The first was a feeling of a complete lack of respect and value; it is just so damaging to morale – the feeling that you don’t count.

“School leaders’ pay is not bad when you compare it with the public sector. But whenever you sit down and look at what they do – in Northern Ireland, there is a completely open-ended contractual situation. That means everything and anything can end up falling to the principal every time,” he says.

“The second factor that members raised, again and again, is that in Northern Ireland, principals and vice-principals, people in leadership roles, don’t have access to any other form of remuneration or recompense for additional responsibilities.

“So, for example, if you’re a teacher and take on the role of special needs coordinator, you will get one or two teaching allowances for that. What we’ve seen over the past decade is school leaders increasingly taking on these really big roles, first, to save finances for the school and, second, because quite often, teachers just don’t want to do them. But whenever a principal or vice-principal takes on this role, there is no recompense for them; they aren’t entitled to any additional allowances.

“People are just at the end of their tether. Incoming calls to the office about health concerns are up. Incoming calls to the office about retirement and looking at options for leaving the profession are up. Even just anecdotally, there is such a sense of desolation out there; it is really awful,” Graham adds.