Leadership Focus journalist Nic Paton chats to the new NAHT president about his role, expectations for the next 12 months and what makes him tick.

PAUL GOSLING

NAHT PRESIDENT

“I believe NAHT is rooted in compassion, humanity and solidarity. Compassion for those living in poverty by actively campaigning to end child poverty … Humanity in understanding that being a parent or carer is not an easy job … And standing in solidarity with our colleagues as we campaign for better pay for those working in education and better funding for schools and academies.”

This is what new NAHT president Paul Gosling said to Annual Conference in April. In the process he encapsulated not just NAHT’s core priority campaign themes as we head into the autumn but also what the key narratives of his presidency will be over the next 12 months.

“I think we need to translate the anger many of us feel about how the profession has been treated over the past few years – in fact, the past decade – into energy, and then that energy into action; do something about it,” Paul tells Leadership Focus.

PAUL GOSLING

NAHT PRESIDENT

“I believe NAHT is rooted in compassion, humanity and solidarity. Compassion for those living in poverty by actively campaigning to end child poverty … Humanity in understanding that being a parent or carer is not an easy job … And standing in solidarity with our colleagues as we campaign for better pay for those working in education and better funding for schools and academies.”

This is what new NAHT president Paul Gosling said to Annual Conference in April. In the process he encapsulated not just NAHT’s core priority campaign themes as we head into the autumn but also what the key narratives of his presidency will be over the next 12 months.

“I think we need to translate the anger many of us feel about how the profession has been treated over the past few years – in fact, the past decade – into energy, and then that energy into action; do something about it,” Paul tells Leadership Focus.

“Don’t sit on your hands; get out there. If you get involved in NAHT at branch or regional level, it can give you an outlet. At least you will feel like you are doing something when things aren’t quite right, that you have some sort of voice,” he adds.

A native of east London, Paul began his teaching career in Canning Town in the London Borough of Newham before relocating to Devon in 2001, where he is currently head teacher at Exeter Road Community Primary School in Exmouth. The school is part of The Avocet Learning Trust, a cooperative trust of three local primary schools.

An NAHT member throughout his leadership career, from 2010 he was NAHT branch secretary for Devon, Torbay and Plymouth and part of the NAHT south-west executive. He became a national executive member in 2016, representing the south-west region, and then, last year, national vice-president before stepping up to president at conference in April.

“Don’t sit on your hands; get out there. If you get involved in NAHT at branch or regional level, it can give you an outlet. At least you will feel like you are doing something when things aren’t quite right, that you have some sort of voice,” he adds.

A native of east London, Paul began his teaching career in Canning Town in the London Borough of Newham before relocating to Devon in 2001, where he is currently head teacher at Exeter Road Community Primary School in Exmouth. The school is part of The Avocet Learning Trust, a cooperative trust of three local primary schools.

An NAHT member throughout his leadership career, from 2010 he was NAHT branch secretary for Devon, Torbay and Plymouth and part of the NAHT south-west executive. He became a national executive member in 2016, representing the south-west region, and then, last year, national vice-president before stepping up to president at conference in April.

So, that’s the basics, but what makes Paul tick?

“We all need to stand together – to put across the message that this government simply isn’t thinking about the vast majority of people in this country,” he emphasises.

“My priority this year is to raise the level of activism; to turn people’s frustrations into positive energy, particularly directed towards our five priority campaigns – restoring pay in education, fixing school funding, ending child poverty, investing in pupil and family services and ending forced academisation. I want people to be getting up off their knees and talking about these things that are so important,” he adds.

“During the pandemic, some terrible messaging came out from Ofsted and the Department for Education. They just weren’t thinking about how people operate; those announcements that landed at 11pm on a Friday or Sunday,” he says.

“We seem to be treated by this government, in England at least, as if we are just some sort of service class. In one sense, I haven’t got a problem with that – I recognise I am a public servant. But we should be collaborating to succeed for the children.

“The government needs to work with us, the profession. We want the best for children, and so do they. So, let’s really listen to each other – and ministers need to listen to what the profession is saying through NAHT.

“We’re not a tub-thumping union that is always just banging on about our pay and conditions; we have wider concerns about society, the futures of our children and staffing the system. We also have the collective wisdom of tens of thousands of people. So, treat us with humanity, listen to us, and we can achieve great things together,” Paul argues.

This message, in turn, feeds into NAHT’s campaigning messages, especially around child poverty and wider school funding. These, as we’re addressing in more detail elsewhere in Leadership Focus, are not the normal ‘bread-and-butter’ campaigning messages of a trade union, Paul readily concedes. But they are vital conversations that NAHT and the wider profession need to be articulating.

“It is pretty pointless of the government coming up with targets for 2030 for reading, writing and maths if we have increasing child poverty,” Paul points out. “All of the literature – and my doctorate looked at this very issue: the barriers to educational success among socio-economically disadvantaged people – says if you have a growing population of people in poverty, then you are going to have poor educational outcomes for those groups.

“Just telling head teachers to work harder and get poorer children through the school system is missing the point. It is coming in at the wrong place. Let’s reduce the problem to start with; let’s all work as a society on reducing poverty, and then the education system will be able to flourish. At the moment, we just keep fighting against overcoming barriers created by socio-economic disadvantages for children. And that hinders the whole system. It is about that holistic approach.

“On top of that, we need to get across the fact that services for children and their families – from CAMHS [Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services] and social services to children’s centres – are in a dire state currently, and the impact that has, and that is down to a lack of investment,” Paul adds.

“During the pandemic, some terrible messaging came out from Ofsted and the Department for Education. They just weren’t thinking about how people operate; those announcements that landed at 11pm on a Friday or Sunday,” he says.

“We seem to be treated by this government, in England at least, as if we are just some sort of service class. In one sense, I haven’t got a problem with that – I recognise I am a public servant. But we should be collaborating to succeed for the children.

“The government needs to work with us, the profession. We want the best for children, and so do they. So, let’s really listen to each other – and ministers need to listen to what the profession is saying through NAHT.

“We’re not a tub-thumping union that is always just banging on about our pay and conditions; we have wider concerns about society, the futures of our children and staffing the system. We also have the collective wisdom of tens of thousands of people. So, treat us with humanity, listen to us, and we can achieve great things together,” Paul argues.

This message, in turn, feeds into NAHT’s campaigning messages, especially around child poverty and wider school funding. These, as we’re addressing in more detail elsewhere in Leadership Focus, are not the normal ‘bread-and-butter’ campaigning messages of a trade union, Paul readily concedes. But they are vital conversations that NAHT and the wider profession need to be articulating.

“It is pretty pointless of the government coming up with targets for 2030 for reading, writing and maths if we have increasing child poverty,” Paul points out. “All of the literature – and my doctorate looked at this very issue: the barriers to educational success among socio-economically disadvantaged people – says if you have a growing population of people in poverty, then you are going to have poor educational outcomes for those groups.

“Just telling head teachers to work harder and get poorer children through the school system is missing the point. It is coming in at the wrong place. Let’s reduce the problem to start with; let’s all work as a society on reducing poverty, and then the education system will be able to flourish. At the moment, we just keep fighting against overcoming barriers created by socio-economic disadvantages for children. And that hinders the whole system. It is about that holistic approach.

“On top of that, we need to get across the fact that services for children and their families – from CAMHS [Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services] and social services to children’s centres – are in a dire state currently, and the impact that has, and that is down to a lack of investment,” Paul adds.

What, then, of the Paul Gosling beyond the school gate?

Growing up in east London, near Victoria Docks, Paul recalls his amazement as a child of finally getting out of the capital into the green fields and natural world.

“I remember a holiday in 1976 to Devon, where I now live. I couldn’t believe seeing buzzards for the first time. So, I have always had a passion for natural history and have been a member of local conservation clubs and RSPB [Royal Society for the Protection of Birds] groups since I was eight years old,” Paul says.

His family has also been close support throughout his working life, particularly in helping to mitigate the stresses and strains of senior leadership. “I’m very lucky; I have a brilliant family, with a very supportive wife, Siân. We’ve been married for 22 years, and we have two children aged 18 and 16; Sophie’s at university in London, and Joe is doing his A levels. I am very well supported," he adds.

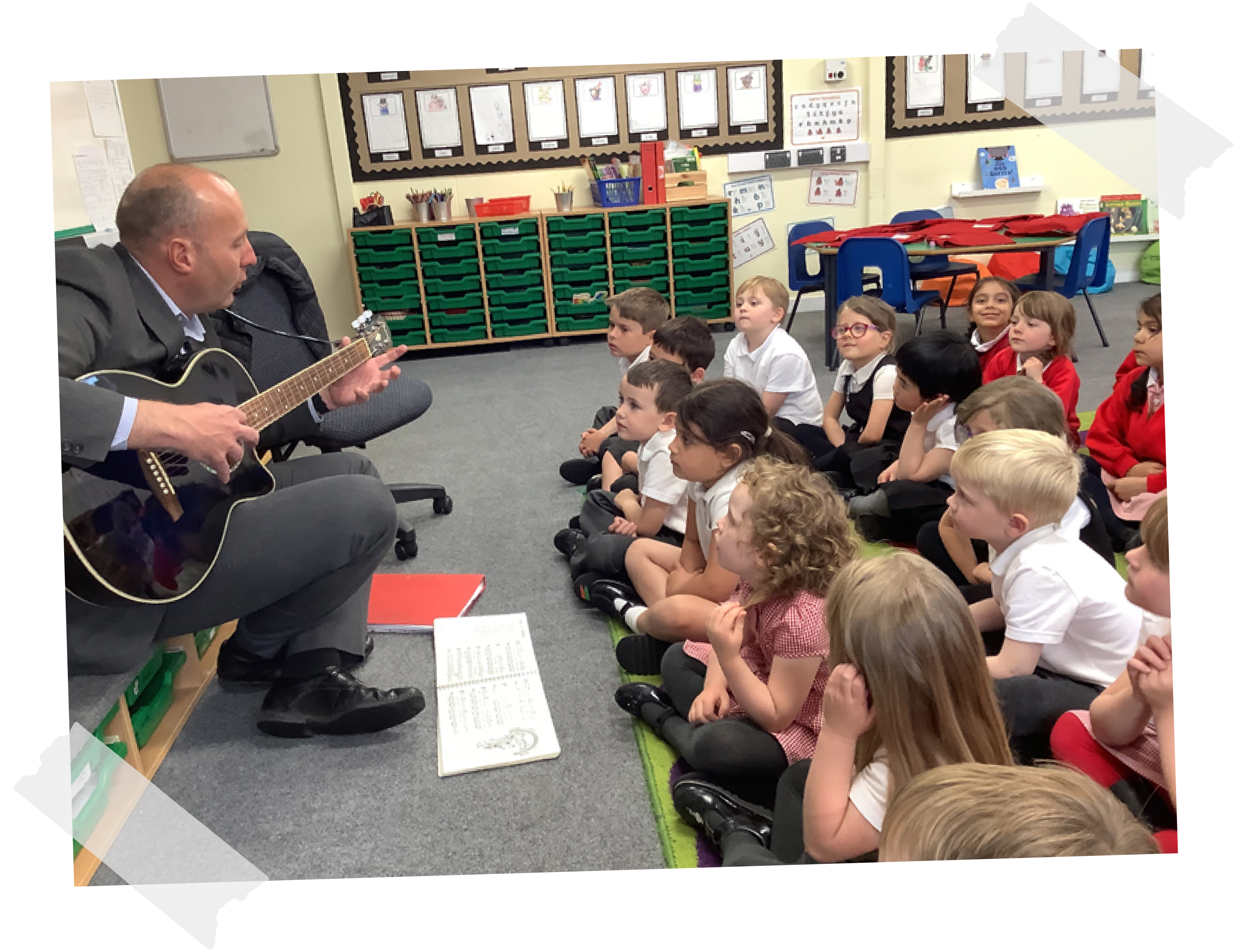

And then – not least given the prominence of the guitar propped up against the wall behind him when we talk – there’s the band. “I took up music, playing the guitar in an indie band, at university,” Paul explains.

“After university, we played a lot of gigs in London; we recorded some albums. I’d pretty much describe it as a post-Britpop era band with a slice of electronica! Occasionally, I sing – though we are trying to find someone better-looking than me to do that.

“More recently, during lockdown, I moved over to the bass guitar because I quite like, at my age now, to play along to records. Playing along on the bass is quite satisfying.

“From where I live, I can quite easily walk to the River Exe in 15 minutes. I can get some beautiful views of the sea, the estuary and the commons around here. And when it is raining, I can play music. All that is great for my mental health, which of course is important for all school leaders to look after,” Paul says.

What, then, of the Paul Gosling beyond the school gate?

Growing up in east London, near Victoria Docks, Paul recalls his amazement as a child of finally getting out of the capital into the green fields and natural world.

“I remember a holiday in 1976 to Devon, where I now live. I couldn’t believe seeing buzzards for the first time. So, I have always had a passion for natural history and have been a member of local conservation clubs and RSPB [Royal Society for the Protection of Birds] groups since I was eight years old,” Paul says.

His family has also been close support throughout his working life, particularly in helping to mitigate the stresses and strains of senior leadership. “I’m very lucky; I have a brilliant family, with a very supportive wife, Siân. We’ve been married for 22 years, and we have two children aged 18 and 16; Sophie’s at university in London, and Joe is doing his A levels. I am very well supported," he adds.

And then – not least given the prominence of the guitar propped up against the wall behind him when we talk – there’s the band. “I took up music, playing the guitar in an indie band, at university,” Paul explains.

“After university, we played a lot of gigs in London; we recorded some albums. I’d pretty much describe it as a post-Britpop era band with a slice of electronica! Occasionally, I sing – though we are trying to find someone better-looking than me to do that.

“More recently, during lockdown, I moved over to the bass guitar because I quite like, at my age now, to play along to records. Playing along on the bass is quite satisfying.

“From where I live, I can quite easily walk to the River Exe in 15 minutes. I can get some beautiful views of the sea, the estuary and the commons around here. And when it is raining, I can play music. All that is great for my mental health, which of course is important for all school leaders to look after,” Paul says.

Paul's nominated charity for his year as president is CRY, or Cardiac Risk in the Young – and it’s a very personal choice, as Paul explains.

“My brother-in-law Huw died 20 years ago this October; he was the same age as me at the time, so he was in his 30s,” Paul says.

“He had a daughter, and his wife was pregnant with their second child. He was fit and ran the London Marathon – and he collapsed and died while playing football; he was dead before he hit the floor. With no outward signs beforehand.

“Twelve people aged between 14 and 25 and older die a week - a week - from conditions that can be screened for; preventable deaths. In Italy, for example, anyone taking part in competitive sport has to have a heart ECG (electrocardiogram) check to make sure they don’t have any conditions that might kill them.

“At the time that Huw died, it was the first tragic death we had had in the family. And CRY was brilliant. A lot of them involved in the charity are doctors and medical professionals who know how easy it is to screen for heart abnormalities.

“Part of the charity’s work is to put on screening events at competitions and sports festivals. For £6,000, they can get an ECG van there that can screen 100 people, and out of those young people, they will pick up two or three who need further exploration and may need medication.

“So, it is very personal to my wife’s family and me. They are a relatively small charity, but mostly, it is about awareness-raising. If you have a young person, get their heart checked out if they are taking part in sport. It will also affect pupils in our schools; it will affect young teachers and leaders who participate in events that raise their heart rate through sport,” Paul says.

You can find out more about NAHT’s support for CRY and its important work here: www.naht.org.uk/cry

Paul's nominated charity for his year as president is CRY, or Cardiac Risk in the Young – and it’s a very personal choice, as Paul explains.

“My brother-in-law Huw died 20 years ago this October; he was the same age as me at the time, so he was in his 30s,” Paul says.

“He had a daughter, and his wife was pregnant with their second child. He was fit and ran the London Marathon – and he collapsed and died while playing football; he was dead before he hit the floor. With no outward signs beforehand.

“Twelve people aged between 14 and 25 and older die a week - a week - from conditions that can be screened for; preventable deaths. In Italy, for example, anyone taking part in competitive sport has to have a heart ECG (electrocardiogram) check to make sure they don’t have any conditions that might kill them.

“At the time that Huw died, it was the first tragic death we had had in the family. And CRY was brilliant. A lot of them involved in the charity are doctors and medical professionals who know how easy it is to screen for heart abnormalities.

“Part of the charity’s work is to put on screening events at competitions and sports festivals. For £6,000, they can get an ECG van there that can screen 100 people, and out of those young people, they will pick up two or three who need further exploration and may need medication.

“So, it is very personal to my wife’s family and me. They are a relatively small charity, but mostly, it is about awareness-raising. If you have a young person, get their heart checked out if they are taking part in sport. It will also affect pupils in our schools; it will affect young teachers and leaders who participate in events that raise their heart rate through sport,” Paul says.

You can find out more about NAHT’s support for CRY and its important work here: www.naht.org.uk/cry