SEND:

A system at breaking point

SEND:

A system at breaking point

Parents exhausted, teachers overstretched and children slipping through the cracks – the latest Education Select Committee report lays bare the reality of a special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) system in crisis. Journalist Nic Paton asks how we can rebuild hope and support for those who need it most.

Context and scale of the SEND crisis

Since the introduction of the Children and Families Act 2014, the number of children and young people identified with special educational needs (SEN) has surged from 1.3 million to 1.7 million.

This opening paragraph, taken from what is in many respects a coruscating report by MPs from the highly influential Education Select Committee, sums up neatly one aspect of why special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) in this country is now routinely described as ‘in crisis’.

Moreover, the report, ‘Solving the SEND crisis’, published in September, doesn’t get any cheerier as you read on. “Exhausted” parents are “fighting” for basic support; families are “navigating a system that too often feels adversarial, fragmented and under-resourced”; teachers are “stretched beyond capacity” and “committed professionals working within services [are] buckling under pressure”.

The September timing of the report was, of course, deliberate, given that we were initially expecting publication of the government’s Schools White Paper during ‘the autumn’, before it was revealed in October that it is now not expected to see the light of day until early 2026. The Department for Education (DfE) has articulated that it will “set out an ambitious vision for improving outcomes for all pupils – in particular, those with SEND and from white working-class backgrounds”.

It is a vision that is sorely needed, the committee emphasised, arguing that: “Without decisive, long-term change, the SEND system will remain under unsustainable pressure, unable to meet current or future needs effectively.” (See the panel at the end for more detail on its recommendations.)

Before we get to this reform conversation, however – and what NAHT is doing to try to make it a reality – it is important to remember that in any discussion about SEND (provision and/or reform), at its heart are children and their futures.

Context and scale of the SEND crisis

Since the introduction of the Children and Families Act 2014, the number of children and young people identified with special educational needs (SEN) has surged from 1.3 million to 1.7 million.

This opening paragraph, taken from what is in many respects a coruscating report by MPs from the highly influential Education Select Committee, sums up neatly one aspect of why special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) in this country is now routinely described as ‘in crisis’.

Moreover, the report, ‘Solving the SEND crisis’, published in September, doesn’t get any cheerier as you read on. “Exhausted” parents are “fighting” for basic support; families are “navigating a system that too often feels adversarial, fragmented and under-resourced”; teachers are “stretched beyond capacity” and “committed professionals working within services [are] buckling under pressure”.

The September timing of the report was, of course, deliberate, given that we were initially expecting publication of the government’s Schools White Paper during ‘the autumn’, before it was revealed in October that it is now not expected to see the light of day until early 2026. The Department for Education (DfE) has articulated that it will “set out an ambitious vision for improving outcomes for all pupils – in particular, those with SEND and from white working-class backgrounds”.

It is a vision that is sorely needed, the committee emphasised, arguing that: “Without decisive, long-term change, the SEND system will remain under unsustainable pressure, unable to meet current or future needs effectively.” (See the panel at the end for more detail on its recommendations.)

Before we get to this reform conversation, however – and what NAHT is doing to try to make it a reality – it is important to remember that in any discussion about SEND (provision and/or reform), at its heart are children and their futures.

Leadership and cultural change

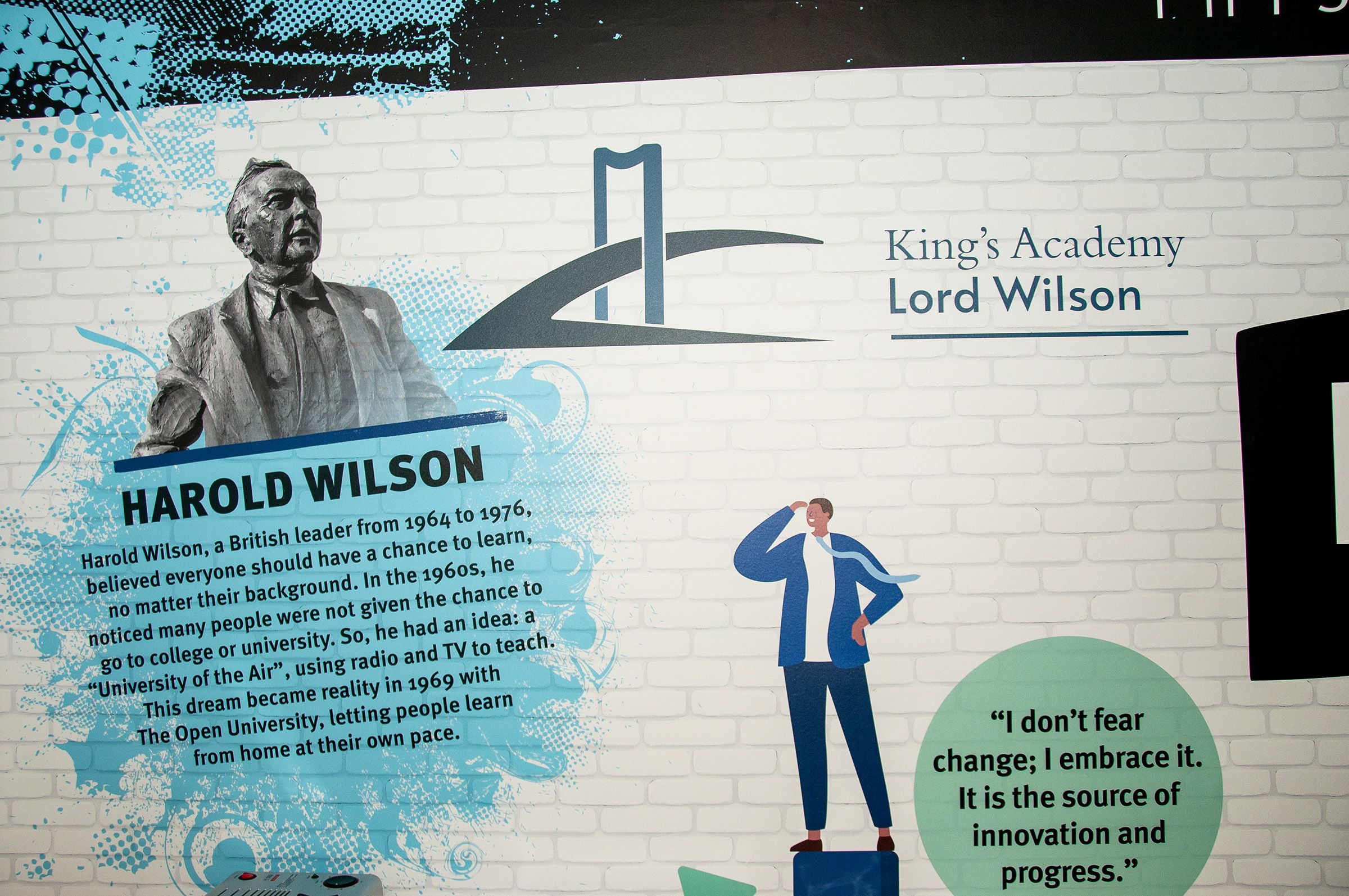

And, when you listen to someone like Dr Nigel (Nige) Matthias, head teacher of King’s Academy Lord Wilson, a boys-only special school in Southampton, Hampshire, you hear up close and personal the amazing dedication and commitment of all those who work – and struggle – to make the best of the current, flawed system.

DR NIGE MATTHIAS,

HEAD TEACHER, KING'S ACADEMY LORD WILSON

“When I arrived two years ago, I remember being told not to put any screens up because they would just get smashed,” Nige tells Leadership Focus. “On the morning of the latest exams, it was amazing to see the children come in and sit in the canteen with a revision video, making notes. You have to believe in your children. We’ve shown faith in them, a belief that they could succeed.”

The school has 62 pupils on roll, all with education, health and care plans (EHCPs). Some had been permanently excluded from mainstream provision, and some from pupil referral units after that. Some have physical disabilities, while others have neurodiversity requirements.

“In terms of the range of need, it is huge. While the school had achieved a ‘good’ Ofsted, in terms of exam outcomes, the pupils were achieving broadly in line with the national average for special needs, which is stunningly low. That was something I felt wasn’t fair for the children or reflective of what they could achieve,” Nige adds.

From a position where no student had previously achieved the GCSE grades required to access level three at college, around half of the cohort did so last year. Its GCSE results now place the school in the top one per cent nationally for special schools, according to the FFT’s Attainment 5 measure; this led to Nige being shortlisted for the TES Specialist School Headteacher of the Year Award and the school’s teaching assistant, Jackie Lunt, winning the Teaching Assistant of the Year Award.

Changes have included a new uniform, school name and logo, a new mobile phone policy and a new structured start to the day, among others. Securing additional – and much-needed – investment to make the school estate feel more welcoming has also been crucial.

“They may seem like small things, but it was all about a cultural change,” says Nige. “A compounding challenge when I got here was that the physical estate was in a really bad way. There is a drain in the main corridor that twice pumped sewage into the school, and we had to close. The roof collapsed in the staffroom, and we had water coming in through the ceiling of one of the classrooms.

“My deputy and I also spent so much time applying for grant funding. We got Sport England to pay for a new gym, we had another charitable donation to build a climbing wall and Ford Community Trust sponsored our e-sports room; we secured 20+ grants because otherwise we would just not have had the money. You walk around the school now and, while it is still a very old building – and was, in fact, an asylum before it became a school – it feels a lot brighter and more welcoming. We have vinyl wraps on the walls in the corridors and really make it feel like a lovely learning environment.

“Educationally, what I wanted to do was flip the script and not be talking about behaviour every day. We know that these children are here because of their behaviour principally (well because of their need, but often that is manifested in behaviour), so my ethos was ‘Let’s talk about curriculum, pathways and attainment – let’s see what we can do’,” he adds.

“We looked at what conditions each student would need in order to achieve success. It could be temperature regulation (making sure the room was air-conditioned), food and drink (ensuring they had eaten) or having a trusted adult (someone who would collect them on the morning of each exam).

“We made bite-sized revision clips for each subject, which we recorded in school, and then got their trusted adult to voiceover. These were then sent out to all the parents so that, the night before the exam, they were hearing the adult they had worked most frequently with throughout the year talk to them about, say, their simultaneous equations or the film The Lost Boys or whatever it was they were studying. It took a lot of time and effort, but we really tried to make sure there was no stone left unturned in terms of the supportive conditions,” Nige adds.

System-level pressure and professional strain

Of course, this is just one example of best practice and dedication making a tangible, positive difference on the ground.

Effecting tangible, positive, ground-level, systemic change – in effect, turning around the ‘failing’ super tanker that is SEND provision – is likely to be a hugely complex and challenging ask, and certainly one without a quick fix, as NAHT assistant general secretary James Bowen fully recognises.

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

“For me, it is one of those areas of education policy where almost everybody agrees the system is not currently working. It is not working for parents, it is not working for schools, and it is not working as well as it could for pupils, despite schools’ best efforts. Almost everyone agrees that reform is needed,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“The challenge is, where do you start? We cannot escape the fact that we have more children with more complex needs than ever before. The government has spoken a lot about wanting to focus on more children being educated in mainstream education and mainstream schools. I think, in principle, everyone wants to see an inclusive system.

“However, I do think, despite that, there is probably still a need to increase the number of specialist places available. The government might want more pupils in mainstream education, but there are still more pupils coming through with complex needs. For some of those, specialist provision is the right answer, and we have to not lose sight of that. If you look at the demand on special school places that there is now, we clearly do need more special school places as part of this.

“The second point I would say is if we are going to have more children with SEND in mainstream, then those schools have to be properly resourced to meet those children’s needs. A couple of training sessions or just new guidance from the government will not be nearly enough for what we need.

“There will need to be an investment in mainstream schools to enable them to have the confidence to say to parents, ‘Yes, we can meet your child’s needs’. Some of that might come through increased ‘resourced provision’ – but equally, it will be about making sure that schools have the resources they need.

“We have to have an honest conversation about the level of need that is currently in the system and a needs-led approach. That has to be at the heart of this. Finally, the government will have to take parents with them as well as the profession. If it wants to reduce the number of EHCPs, which seems to be one of the things the government is saying, it will have to be able to give parents, and indeed schools, the confidence that those children’s needs will be met without them. So, I think there is a huge amount of confidence-building that the government will have to do,” James adds.

MARIJKE MILES,

HEAD TEACHER, BAYCROFT SCHOOL

Marijke Miles, head teacher at Baycroft School in Fareham, Hampshire, and chair of NAHT’s SEND and Alternative Provision Sector Council, points to a combination of factors: rising demand (as seen in the spiralling of EHCPs), the erosion and diminishment of funding over many years and successive governments and the ‘hollowing out’ of complementary support services – such as social care and the NHS – which means schools and school leaders are too often expected to pick up the slack.

She highlights official figures suggesting that the percentage of children in state-funded special schools has gone from 1.4% to 1.8% in the last five years; that’s around a 27% increase. “That is an astonishing increase. The number of children with EHCPs has grown from 3.3% to 5.3% in five years, of the entire school pupil population, which is massive. Without reforms, the Institute for Fiscal Studies projects that it will rise to eight per cent by 2029,” she tells Leadership Focus.

“There are more children with increasingly complex needs than ever before, in net terms. We know that schools are becoming progressively less resourced and equipped to support these students, not least because of pressures – not merely financial but also on structures, curriculum, outcomes and accountability levers.

“The system is just overwhelmed. The peripheral and supportive services, too, are themselves diminishing. It is like a badly baked cake where more and more ingredients are being taken out. You could probably tolerate a bit less margarine, but when the eggs are also going and there is not enough flour, you just don’t get a cake in the end,” Marijke adds.

For school leaders struggling to maintain the provision they know these children (‘special’ of course in every sense) should be receiving, the impact can be corrosive. “As a profession, we’re just exhausted with apologising. We’re exhausted with not being able to deliver what we really want to,” says Marijke. “School leaders apologise to parents, to children and to our staff – all of whom feel desperate, impotent and at times like failures. When you know that we are one of the most trusted professions, it is an assault on your identity, everything you believe about yourself and why you went into teaching in the first place, when you are seen to let people down.

“Our role is to help and educate children and, as leaders, to build trusted relationships with our communities, especially our families. The daily grind of apologising for things beyond our control. Seeking the undeliverable and undoable. Knowing that we’re often beaten by a hopelessly inadequate system even before we start is really hard. It’s like having to play a game every single day that you know you just can’t win,” she adds.

LIAM KENNY,

NAHT REGIONAL HEAD, SOUTH WEST

“One of the big frustrations for school leaders is that they don’t see real, long-term progress being made. They also know that the health element of the EHCP is not being held accountable. If they can see movement towards some sort of joint-working structure being put in place, then that is a step in the right direction. So, how do we put that together?” agrees Liam Kenny, NAHT regional head, south west, and the union’s liaison with the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities.

This group of MPs published a report with NAHT in July on how to reform SEND in England (and see panel below for more details). “We had numerous organisations come in to give evidence. We have been trying to unpick all the problems and to work out how we can put together constructive ways forward and find things that do work,” Liam says.

“We’ve found a system that is overly combative; the system has created that from all parties involved. Each service – education, local authorities and health – all seem to be defensive of their own budgetary positions and their own workload. They’re also not able to put their head over the parapet because they are firefighting in their own arena. And that’s, of course, a frustration for everyone.

“Yet the one service where a parent can literally knock on someone’s door is the head teacher’s. Or somebody within the school setting. So the impact on school leaders is massive. School leaders are essentially caught in the middle, trying to meet the child’s needs with limited resources and unclear support structures,” he adds.

ROB WILLIAMS,

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISER

This need to make the ‘health’ element of the EHCP work better is something ministers, both in the DfE and the Department of Health and Social Care, do recognise, highlights NAHT senior policy adviser Rob Williams. It is also something that is firmly on the radar of politicians generally because their postbags and inboxes are increasingly full of letters from constituents about this emotive topic.

“They [ministers] have to recognise there has to be some level of investment. I think school leaders, if they can feel and sense improvement taking place, will hold their course. The problem is, at the moment, they get no sense of that, and the government seems to be unable to explain those steps that it wants to get to,” he says.

System-level pressure and professional strain

Of course, this is just one example of best practice and dedication making a tangible, positive difference on the ground.

Effecting tangible, positive, ground-level, systemic change – in effect, turning around the ‘failing’ super tanker that is SEND provision – is likely to be a hugely complex and challenging ask, and certainly one without a quick fix, as NAHT assistant general secretary James Bowen fully recognises.

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

“For me, it is one of those areas of education policy where almost everybody agrees the system is not currently working. It is not working for parents, it is not working for schools, and it is not working as well as it could for pupils, despite schools’ best efforts. Almost everyone agrees that reform is needed,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“The challenge is, where do you start? We cannot escape the fact that we have more children with more complex needs than ever before. The government has spoken a lot about wanting to focus on more children being educated in mainstream education and mainstream schools. I think, in principle, everyone wants to see an inclusive system.

“However, I do think, despite that, there is probably still a need to increase the number of specialist places available. The government might want more pupils in mainstream education, but there are still more pupils coming through with complex needs. For some of those, specialist provision is the right answer, and we have to not lose sight of that. If you look at the demand on special school places that there is now, we clearly do need more special school places as part of this.

“The second point I would say is if we are going to have more children with SEND in mainstream, then those schools have to be properly resourced to meet those children’s needs. A couple of training sessions or just new guidance from the government will not be nearly enough for what we need.

“There will need to be an investment in mainstream schools to enable them to have the confidence to say to parents, ‘Yes, we can meet your child’s needs’. Some of that might come through increased ‘resourced provision’ – but equally, it will be about making sure that schools have the resources they need.

“We have to have an honest conversation about the level of need that is currently in the system and a needs-led approach. That has to be at the heart of this. Finally, the government will have to take parents with them as well as the profession. If it wants to reduce the number of EHCPs, which seems to be one of the things the government is saying, it will have to be able to give parents, and indeed schools, the confidence that those children’s needs will be met without them. So, I think there is a huge amount of confidence-building that the government will have to do,” James adds.

MARIJKE MILES,

HEAD TEACHER, BAYCROFT SCHOOL

Marijke Miles, head teacher at Baycroft School in Fareham, Hampshire, and chair of NAHT’s SEND and Alternative Provision Sector Council, points to a combination of factors: rising demand (as seen in the spiralling of EHCPs), the erosion and diminishment of funding over many years and successive governments and the ‘hollowing out’ of complementary support services – such as social care and the NHS – which means schools and school leaders are too often expected to pick up the slack.

She highlights official figures suggesting that the percentage of children in state-funded special schools has gone from 1.4% to 1.8% in the last five years; that’s around a 27% increase. “That is an astonishing increase. The number of children with EHCPs has grown from 3.3% to 5.3% in five years, of the entire school pupil population, which is massive. Without reforms, the Institute for Fiscal Studies projects that it will rise to eight per cent by 2029,” she tells Leadership Focus.

“There are more children with increasingly complex needs than ever before, in net terms. We know that schools are becoming progressively less resourced and equipped to support these students, not least because of pressures – not merely financial but also on structures, curriculum, outcomes and accountability levers.

“The system is just overwhelmed. The peripheral and supportive services, too, are themselves diminishing. It is like a badly baked cake where more and more ingredients are being taken out. You could probably tolerate a bit less margarine, but when the eggs are also going and there is not enough flour, you just don’t get a cake in the end,” Marijke adds.

For school leaders struggling to maintain the provision they know these children (‘special’ of course in every sense) should be receiving, the impact can be corrosive. “As a profession, we’re just exhausted with apologising. We’re exhausted with not being able to deliver what we really want to,” says Marijke. “School leaders apologise to parents, to children and to our staff – all of whom feel desperate, impotent and at times like failures. When you know that we are one of the most trusted professions, it is an assault on your identity, everything you believe about yourself and why you went into teaching in the first place, when you are seen to let people down.

“Our role is to help and educate children and, as leaders, to build trusted relationships with our communities, especially our families. The daily grind of apologising for things beyond our control. Seeking the undeliverable and undoable. Knowing that we’re often beaten by a hopelessly inadequate system even before we start is really hard. It’s like having to play a game every single day that you know you just can’t win,” she adds.

LIAM KENNY,

NAHT REGIONAL HEAD, SOUTH WEST

“One of the big frustrations for school leaders is that they don’t see real, long-term progress being made. They also know that the health element of the EHCP is not being held accountable. If they can see movement towards some sort of joint-working structure being put in place, then that is a step in the right direction. So, how do we put that together?” agrees Liam Kenny, NAHT regional head, south west, and the union’s liaison with the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities.

This group of MPs published a report with NAHT in July on how to reform SEND in England (and see panel below for more details). “We had numerous organisations come in to give evidence. We have been trying to unpick all the problems and to work out how we can put together constructive ways forward and find things that do work,” Liam says.

“We’ve found a system that is overly combative; the system has created that from all parties involved. Each service – education, local authorities and health – all seem to be defensive of their own budgetary positions and their own workload. They’re also not able to put their head over the parapet because they are firefighting in their own arena. And that’s, of course, a frustration for everyone.

“Yet the one service where a parent can literally knock on someone’s door is the head teacher’s. Or somebody within the school setting. So the impact on school leaders is massive. School leaders are essentially caught in the middle, trying to meet the child’s needs with limited resources and unclear support structures,” he adds.

ROB WILLIAMS,

NAHT SENIOR POLICY ADVISER

This need to make the ‘health’ element of the EHCP work better is something ministers, both in the DfE and the Department of Health and Social Care, do recognise, highlights NAHT senior policy adviser Rob Williams. It is also something that is firmly on the radar of politicians generally because their postbags and inboxes are increasingly full of letters from constituents about this emotive topic.

“They [ministers] have to recognise there has to be some level of investment. I think school leaders, if they can feel and sense improvement taking place, will hold their course. The problem is, at the moment, they get no sense of that, and the government seems to be unable to explain those steps that it wants to get to,” he says.

Reform, confidence and what progress could mean

The hope, of course, is that the white paper will provide much-needed clarity and direction.

Moreover, a white paper that lays out, in effect, a road map for reform and ‘success’ will be critical for restoring parental and school leaders’ confidence in the system, agrees NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

“What this all hangs on, frankly, is parental confidence. It has been such a battle for very many parents to have the support their children need because everything hangs on the EHCP. If you’ve battled for years to get that, you’re not going to give it up easily. You’re going to be very frightened that with it goes the support you need,” he points out.

“The biggest challenges right now are: 1) I’m not sure the government has done enough to win the support of parents on this yet, and 2) there are a lot of unknowns – fear creates a void that can be filled by naysaying voices,” he adds, noting that he fears Conservative and Reform politicians may yet ‘weaponise’ this debate politically as we head through the autumn.

“The problem we have is that the government is talking in very general terms at the moment, and headlines without the detail are worrying. My counsel, however, to everyone at the moment is: ‘We can see the direction of travel. Broadly speaking, if they can bring the resources and support to that direction of travel, we think that is positive. Having said that, we haven’t seen the detail, so we don’t know whether we’re criticising the government or not. Until we see that, it will be very difficult’,” Paul says.

With so much hope and anxiety hanging in equal measure on the white paper, what might ‘success’, or even simply ‘progress’ (to lower the ‘expectations’ goalposts’), look like for school leaders a year from now?

“For me, it would be a really robust plan in place, which hits some of the key priorities that report after report are identifying,” says Marijke.

“There needs to be a commitment to early intervention and identification, because that is clearly the place to start. And there should be a coherent plan for shoring up the services that make a child’s life and placement sustainable by their contribution to a holistic plan,” she adds.

“I think, for me, there needs to be some degree of changing the trajectories,” agrees Rob Williams. “One thing we would be looking for is significantly more children to receive the support they need without resorting to an EHCP. We would also want schools to be able to access additional support where it is really needed – and get it quickly. And there should be recognition of the need to build core budgets that help schools increase their capacity. At the moment, there is no capacity to be strategic and look to the longer term.

“I want to see that change of trajectory, so head teachers are able to say, ‘Oh, this year’s budget has not been quite so tight, so I think I can invest in staffing and training as well as other provision’. I think they [school leaders] will get a sense of momentum. But I do think the government needs to articulate the steps to where we want to get to, and show what resources are going to make this happen, and where they will come from,” he adds.

“Both parents and schools need the government to be very clear about how children will get the support they need, whatever specific reforms are introduced,” says Paul in conclusion.

“It will be about certainty – how those resources will follow the child and, crucially, for those children who have an EHCP, what does that actually mean for them? For me, that transitional phase is going to be very important,” he adds.

Reform, confidence and what progress could mean

The hope, of course, is that the white paper will provide much-needed clarity and direction.

Moreover, a white paper that lays out, in effect, a road map for reform and ‘success’ will be critical for restoring parental and school leaders’ confidence in the system, agrees NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

“What this all hangs on, frankly, is parental confidence. It has been such a battle for very many parents to have the support their children need because everything hangs on the EHCP. If you’ve battled for years to get that, you’re not going to give it up easily. You’re going to be very frightened that with it goes the support you need,” he points out.

“The biggest challenges right now are: 1) I’m not sure the government has done enough to win the support of parents on this yet, and 2) there are a lot of unknowns – fear creates a void that can be filled by naysaying voices,” he adds, noting that he fears Conservative and Reform politicians may yet ‘weaponise’ this debate politically as we head through the autumn.

“The problem we have is that the government is talking in very general terms at the moment, and headlines without the detail are worrying. My counsel, however, to everyone at the moment is: ‘We can see the direction of travel. Broadly speaking, if they can bring the resources and support to that direction of travel, we think that is positive. Having said that, we haven’t seen the detail, so we don’t know whether we’re criticising the government or not. Until we see that, it will be very difficult’,” Paul says.

With so much hope and anxiety hanging in equal measure on the white paper, what might ‘success’, or even simply ‘progress’ (to lower the ‘expectations’ goalposts’), look like for school leaders a year from now?

“For me, it would be a really robust plan in place, which hits some of the key priorities that report after report are identifying,” says Marijke.

“There needs to be a commitment to early intervention and identification, because that is clearly the place to start. And there should be a coherent plan for shoring up the services that make a child’s life and placement sustainable by their contribution to a holistic plan,” she adds.

“I think, for me, there needs to be some degree of changing the trajectories,” agrees Rob Williams. “One thing we would be looking for is significantly more children to receive the support they need without resorting to an EHCP. We would also want schools to be able to access additional support where it is really needed – and get it quickly. And there should be recognition of the need to build core budgets that help schools increase their capacity. At the moment, there is no capacity to be strategic and look to the longer term.

“I want to see that change of trajectory, so head teachers are able to say, ‘Oh, this year’s budget has not been quite so tight, so I think I can invest in staffing and training as well as other provision’. I think they [school leaders] will get a sense of momentum. But I do think the government needs to articulate the steps to where we want to get to, and show what resources are going to make this happen, and where they will come from,” he adds.

“Both parents and schools need the government to be very clear about how children will get the support they need, whatever specific reforms are introduced,” says Paul in conclusion.

“It will be about certainty – how those resources will follow the child and, crucially, for those children who have an EHCP, what does that actually mean for them? For me, that transitional phase is going to be very important,” he adds.

‘I don’t like the narrative around “Oh, SEND is broken”’

Rob Gasson, chief executive of the Wave Trust based in Cornwall and Devon, oversees 11 schools across the south west, 10 of which offer alternative provision.

ROB GASSON,

CHIEF EXECUTIVE, WAVE TRUST

“I remember, as a relatively new head teacher back in 2000, meeting a year 11 student who had come to us essentially functionally illiterate – and so had been in mainstream school for 12 years and yet still couldn’t read.

“Last year, we had a year nine pupil come to us who was the same, so he had been in mainstream school for 10 years and could not read. We taught him to read in six weeks. Although his behaviour is still not perfect by any stretch of the imagination, we have not seen the big blowouts. Guess what, he couldn’t understand anything that was going on.

“That, to me, illustrates how deep-seated this ‘crisis’ is. In my pupil referral units/my alternative provision, we have a population who, broadly, are with us because they have not been able to get an EHCP; they have not had someone who can advocate for them, can navigate through this horribly difficult, combative system.

“I don’t like the word ‘broken’ and I don’t like the narrative around ‘Oh, SEND is broken’. I have staff working their arses off day in and day out, and they’re not broken. Children in my special school and special schools across the country do not want to believe that they are in a broken system.

“But we’re getting many more complex young people referred into the special school who would normally have been picked up by an independent special. I have one class, for example, with 14 children. I don’t physically have the space to put any more children than that in most of the classrooms.

“We can manage – just about – but I am looking at the possibility of having to split that class into three classes. I can’t afford to do that, but I will have to find a way of doing that because teaching those 14 children in one class, they’re not going to get the best education we can offer otherwise. In one year group, there is a seven-year cognitive difference between one pupil and another.

“What would ‘progress’ look like for me? I think moving towards a curriculum that is more inclusive. I think the curriculum, as it is offered in mainstream schools, still fails the most vulnerable.

“If nothing else, ‘progress’ would look like us all accepting how big the problem is, and having an agreed-upon timescale for how we’re going to work our way from A to B with an evidence-based approach. It would also include an understanding of what ‘success’ looks like – what is ‘success’ in this context? After all, if we have record levels of need and nearly record numbers of people not in education, employment or training (NEET), how can we say we have a great education system?”

‘I don’t like the narrative around “Oh, SEND is broken”’

Rob Gasson, chief executive of the Wave Trust based in Cornwall and Devon, oversees 11 schools across the south west, 10 of which offer alternative provision.

ROB GASSON,

CHIEF EXECUTIVE, WAVE TRUST

“I remember, as a relatively new head teacher back in 2000, meeting a year 11 student who had come to us essentially functionally illiterate – and so had been in mainstream school for 12 years and yet still couldn’t read.

“Last year, we had a year nine pupil come to us who was the same, so he had been in mainstream school for 10 years and could not read. We taught him to read in six weeks. Although his behaviour is still not perfect by any stretch of the imagination, we have not seen the big blowouts. Guess what, he couldn’t understand anything that was going on.

“That, to me, illustrates how deep-seated this ‘crisis’ is. In my pupil referral units/my alternative provision, we have a population who, broadly, are with us because they have not been able to get an EHCP; they have not had someone who can advocate for them, can navigate through this horribly difficult, combative system.

“I don’t like the word ‘broken’ and I don’t like the narrative around ‘Oh, SEND is broken’. I have staff working their arses off day in and day out, and they’re not broken. Children in my special school and special schools across the country do not want to believe that they are in a broken system.

“But we’re getting many more complex young people referred into the special school who would normally have been picked up by an independent special. I have one class, for example, with 14 children. I don’t physically have the space to put any more children than that in most of the classrooms.

“We can manage – just about – but I am looking at the possibility of having to split that class into three classes. I can’t afford to do that, but I will have to find a way of doing that because teaching those 14 children in one class, they’re not going to get the best education we can offer otherwise. In one year group, there is a seven-year cognitive difference between one pupil and another.

“What would ‘progress’ look like for me? I think moving towards a curriculum that is more inclusive. I think the curriculum, as it is offered in mainstream schools, still fails the most vulnerable.

“If nothing else, ‘progress’ would look like us all accepting how big the problem is, and having an agreed-upon timescale for how we’re going to work our way from A to B with an evidence-based approach. It would also include an understanding of what ‘success’ looks like – what is ‘success’ in this context? After all, if we have record levels of need and nearly record numbers of people not in education, employment or training (NEET), how can we say we have a great education system?”

‘If another child with an EHCP is directed to our school, we will move into a deficit budget’

Amanda Hulme is head teacher of Claypool Primary School in Bolton, Greater Manchester, which – as well as its 212 mainstream children – has an SEN unit with provision for eight children.

AMANDA HULME,

HEAD TEACHER, CLAYPOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL

“All of our children in the SEN unit have severe learning difficulties and autism and are pre-verbal. We have four members of staff who work with them, and the children are selected by the local authority, with input from us. We do find that the children benefit hugely from this setting; at present, they could not manage in a mainstream classroom.

“The funding is acceptable for the provision; the funding across the rest of the school isn’t. For example, we have a number of children who – if there was space – would be in our SEN unit but are mainstream. They need one-to-one support, and we are expected to find 12 hours of support from a learning support assistant for £6,000, but those things don’t equate; it is more like £8,500. That’s also an issue.

“Moreover, because we have the SEN unit, parents often think that if their child comes to the school, they might have a chance of getting a place there, but that isn’t the case at all; there is a separate admissions criterion organised by the local authority.

“Definitely more resource is needed, more money. But also more training. It feels like a perfect storm is building at the moment. I know everyone is trying to ‘fix’ it, but it is almost like it [the government] hasn’t listened to the profession; it’s not listening to what we’re trying to manage on a daily basis.

“I have 19 children in a one-form entry school with EHCPs, and three pending. And this number is increasing year-on-year. That additional support can’t just be given in the classroom by the class teacher.

“I’m very frugal with our finances, but at the moment, we are very close to going into deficit. If one more child with an EHCP is directed to come to our school, we will be in deficit, and we are prepared for that to be the case if necessary. At the moment, in many ways, it doesn’t pay to be inclusive; it’s no wonder schools end up saying they can’t support a child’s needs.

“Some sort of road map from the government of where it wants to go would certainly be helpful. I hope that when the white paper comes out, it will give us reassurance and support and help us do a better job for the children in our care. But the problem is, I don’t know if the government is fully aware of the issues.

“For me, ‘progress’ would be a sense that we’re finally being funded properly, which is definitely not happening at the moment. Progress would also mean that our children are being well supported by trained staff, and are thriving in our settings."

‘If another child with an EHCP is directed to our school, we will move into a deficit budget’

Amanda Hulme is head teacher of Claypool Primary School in Bolton, Greater Manchester, which – as well as its 212 mainstream children – has an SEN unit with provision for eight children.

AMANDA HULME,

HEAD TEACHER, CLAYPOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL

“All of our children in the SEN unit have severe learning difficulties and autism and are pre-verbal. We have four members of staff who work with them, and the children are selected by the local authority, with input from us. We do find that the children benefit hugely from this setting; at present, they could not manage in a mainstream classroom.

“The funding is acceptable for the provision; the funding across the rest of the school isn’t. For example, we have a number of children who – if there was space – would be in our SEN unit but are mainstream. They need one-to-one support, and we are expected to find 12 hours of support from a learning support assistant for £6,000, but those things don’t equate; it is more like £8,500. That’s also an issue.

“Moreover, because we have the SEN unit, parents often think that if their child comes to the school, they might have a chance of getting a place there, but that isn’t the case at all; there is a separate admissions criterion organised by the local authority.

“Definitely more resource is needed, more money. But also more training. It feels like a perfect storm is building at the moment. I know everyone is trying to ‘fix’ it, but it is almost like it [the government] hasn’t listened to the profession; it’s not listening to what we’re trying to manage on a daily basis.

“I have 19 children in a one-form entry school with EHCPs, and three pending. And this number is increasing year-on-year. That additional support can’t just be given in the classroom by the class teacher.

“I’m very frugal with our finances, but at the moment, we are very close to going into deficit. If one more child with an EHCP is directed to come to our school, we will be in deficit, and we are prepared for that to be the case if necessary. At the moment, in many ways, it doesn’t pay to be inclusive; it’s no wonder schools end up saying they can’t support a child’s needs.

“Some sort of road map from the government of where it wants to go would certainly be helpful. I hope that when the white paper comes out, it will give us reassurance and support and help us do a better job for the children in our care. But the problem is, I don’t know if the government is fully aware of the issues.

“For me, ‘progress’ would be a sense that we’re finally being funded properly, which is definitely not happening at the moment. Progress would also mean that our children are being well supported by trained staff, and are thriving in our settings."

The view from Wales

‘There is massive inconsistency’

We’re working closely with the Welsh Government on achieving improved terms and conditions for additional learning needs coordinators (ALNCos), writes NAHT national secretary (Wales) Laura Doel.

LAURA DOEL,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY (WALES)

We’re pushing for their role to be recognised as a leadership position within schools, as a statutory position. The seniority of the role is linked to appropriate remuneration and non-contact time.

One of the major concerns of ALNCos is that, because of the complexity of the role, they require significant out-of-class contact time. For example, teachers have set planning and preparation time, yet currently, this isn’t stipulated within the school teachers’ pay and conditions document specifically for the ALNCo role, which is ludicrous.

So, we have a very mixed situation across Wales: some ALNCos have non-contact time, some have no teaching commitments, and some are already in the leadership structure while others aren’t. There is a massive inconsistency.

One other issue we have, of course, is next year’s elections in Wales. While we do have a government that, broadly, we feel, understands the issues in Wales, we’re not sure the current government has the political will or strength to do anything about it at this time.

We are months away from a Senedd election and have a Welsh Government that has just announced an additional £8.2 million to support ALN delivery, which is just a drop in the ocean.

A review of the additional learning needs (ALN) legislation has just been published, and it told us nothing new; there is inconsistency, lack of understanding and – unfortunately – learners are being supported by our amazing schools in spite of the legislation rather than because of it.

The Welsh Government has also just announced its draft 2026/27 budget with no additional money for education. That will have a devastating impact on schools and so, one way or another, we will need to start a new dialogue with whoever the new government is going to be.

The view from Northern Ireland

‘The SEND system is in total crisis’

It’s not an exaggeration to say the SEND system in Northern Ireland is in total crisis, writes NAHT national secretary (Northern Ireland) Dr Graham Gault.

DR GRAHAM GAULT,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY (NORTHERN IRELAND)

There are problems in the statutory assessment process, inconsistent implementation of statements and a general lack of support. Schools are left struggling to meet pupils’ needs with completely inadequate resources.

School leaders are increasingly finding themselves acting as case workers and advocates, navigating processes within a system that is broken and functions that don’t work as intended.

We have had chronic under-investment in the special sector here for the past 15 years. It is unclear how many places short the sector is, but every year for the past four or five years, we’ve had a crisis around April/May when 400, 500, 600 children with complex needs have suddenly appeared, requiring places immediately. And mainstream schools are then being asked, ‘Do you have any space?’

Members, rightly, have been very upset about this because it is essentially putting children into schools – any school – to tick a box. Earlier this year, we sent a strongly worded open letter to Northern Ireland’s education authority and education minister demanding urgent talks to ensure this year’s last-minute scramble for school places for children with special educational needs would not be repeated.

In our view, the current situation is totally inadequate, immoral and tantamount to neglect. Absolutely, it is a resourcing problem, just a complete under-investment in the sector and a lack of planning for the future – and this year is looking no different.

For me, ‘progress’ would be, very simply, ministers from all parties ensuring there is enough money. Every year, there is an increasing number of children with complex additional needs here in Northern Ireland, yet not enough places.

If these were A level students, this wouldn’t even be up for discussion. But because we’re talking about children with special needs, there is almost a feeling like meeting their needs is somehow a luxury the system can ill afford.

‘A full system overhaul is required’

The All-Party Parliamentary Group for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities, with NAHT, in its July report, ‘Reforming the SEND System in England’, made a number of key recommendations.

First, it argued, “a full system overhaul is required”, one that must begin with a redesign of the SEND framework to promote joined-up working and clarity of roles.

“A shared vision across all services is needed, supported by legislation that requires collaboration and joint accountability,” the MPs argued.

Funding allocations, the report said, “must be based on robust assessments of need and should empower local areas to innovate”. It continued: “Longer-term financial settlements would provide stability and allow for more strategic planning.”

Alongside this, and to realise fully the government’s drive for inclusion in schools, core mainstream school budgets “need to reflect the level of need they are now expected to support”.

It added that: “For the majority of pupils with low-complexity, high-frequency SEN, core mainstream school budgets must be sufficient to meet their needs without recourse to high-needs top-up funding.”

In addition to money, the government needed to address the SEND workforce crisis by investing in recruitment and retention strategies.

“The system must be reoriented to prioritise early intervention. Funding and policy incentives should reward preventative work, and schools should be supported to identify and address needs as early as possible,” the report recommended.

“Much of the need for more costly and complex interventions later could be reduced if this sector were able to respond quicker and deliver intervention and support sooner,” it added.

Finally, a new accountability structure was essential, the report emphasised. “Responsibilities must be clearly defined, and there should be independent oversight of how well local systems are working. This will create confidence that services are delivering effectively and fairly,” it said.

NAHT’s SEND campaign goals

NAHT is campaigning for sufficiency in core school budgets to meet the needs of the majority of pupils.

It wants a new high-needs funding strategy that ensures long-term sufficiency to properly meet pupils’ additional needs.

It wants cancellation of local authority high-needs deficits to stop the debt from consuming funding set aside for children and young people with SEND. Alongside this, NAHT would like to see greater consistency in the levels and distribution of high-needs funding nationally to meet SEND provision costs fully.

The union is calling for long-term investment in specialist external support services to build capacity and improve speed of access for pupils with SEND.

Furthermore, it is campaigning for an EHCP system that focuses only on those pupils who require a specialist plan and ensures schools do not have to cover the insufficiencies in health and social care capacity.

NAHT is also pressing for wider reform to ensure that education benefits all children and young people.

This includes the following:

• A reformed model of SEN funding for mainstream schools, special schools and alternative provision that provides certainty for a minimum of three years

• A fundamental review of place-planning, sufficiency of specialist places and admissions to ensure that pupils with SEND are able to attend the school that best meets their long-term needs

• An improved accountability system that properly recognises and acknowledges the progress that all pupils make, including those with SEND.

What MPs want to see

In its report, ‘Solving the SEND crisis’, the Education Select Committee set out what it termed “a vision for how the government can realise its laudable aim of making mainstream education inclusive to the vast majority of children and young people with SEND, who are present in every classroom”.

Alongside this, it argued, there must be an increase in the number of specialist state school places so that more children can be educated close to home, thereby reducing the cost of transport and expensive independent school places.

HELEN HAYES,

EDUCATION SELECT COMMITTEE CHAIR

As committee chair Helen Hayes put it: “Making sure every child in the country with SEND can attend a local school that meets their needs will require a root-and-branch transformation. SEND must become the business of every front-line professional in educational settings, with in-depth training at the start and throughout the careers of teachers, senior leaders and teaching assistants.”

Within its upcoming white paper, the MPs argued that the government needed to first define and articulate what ‘inclusive’ mainstream education means.

Ministers also needed to tackle head-on the current inconsistency in SEN support and ordinarily available provision, address the current ‘unsustainable’ demand for EHCPs and better equip and train the SEN workforce.

Furthermore, it would need to put in place a ‘sustainable’ model of funding, ensure NHS services are no longer ‘too passive’ when it comes to SEN provision and, very simply, restore trust and confidence, the committee recommended.

“The government must develop a standardised, national framework for the support that children with SEND can expect in school, long before requiring an EHCP, so that there can be confidence and clear lines of accountability,” said Helen.

“In the long term, a genuinely inclusive, well-resourced mainstream education system will bring down the desperate struggle to obtain an EHCP. This will also help stabilise the sector financially,” she added.

NAHT’s SEND campaign goals

NAHT is campaigning for sufficiency in core school budgets to meet the needs of the majority of pupils.

It wants a new high-needs funding strategy that ensures long-term sufficiency to properly meet pupils’ additional needs.

It wants cancellation of local authority high-needs deficits to stop the debt from consuming funding set aside for children and young people with SEND. Alongside this, NAHT would like to see greater consistency in the levels and distribution of high-needs funding nationally to meet SEND provision costs fully.

The union is calling for long-term investment in specialist external support services to build capacity and improve speed of access for pupils with SEND.

Furthermore, it is campaigning for an EHCP system that focuses only on those pupils who require a specialist plan and ensures schools do not have to cover the insufficiencies in health and social care capacity.

NAHT is also pressing for wider reform to ensure that education benefits all children and young people.

This includes the following:

• A reformed model of SEN funding for mainstream schools, special schools and alternative provision that provides certainty for a minimum of three years

• A fundamental review of place-planning, sufficiency of specialist places and admissions to ensure that pupils with SEND are able to attend the school that best meets their long-term needs

• An improved accountability system that properly recognises and acknowledges the progress that all pupils make, including those with SEND.

What MPs want to see

In its report, ‘Solving the SEND crisis’, the Education Select Committee set out what it termed “a vision for how the government can realise its laudable aim of making mainstream education inclusive to the vast majority of children and young people with SEND, who are present in every classroom”.

Alongside this, it argued, there must be an increase in the number of specialist state school places so that more children can be educated close to home, thereby reducing the cost of transport and expensive independent school places.

HELEN HAYES,

EDUCATION SELECT COMMITTEE CHAIR

As committee chair Helen Hayes put it: “Making sure every child in the country with SEND can attend a local school that meets their needs will require a root-and-branch transformation. SEND must become the business of every front-line professional in educational settings, with in-depth training at the start and throughout the careers of teachers, senior leaders and teaching assistants.”

Within its upcoming white paper, the MPs argued that the government needed to first define and articulate what ‘inclusive’ mainstream education means.

Ministers also needed to tackle head-on the current inconsistency in SEN support and ordinarily available provision, address the current ‘unsustainable’ demand for EHCPs and better equip and train the SEN workforce.

Furthermore, it would need to put in place a ‘sustainable’ model of funding, ensure NHS services are no longer ‘too passive’ when it comes to SEN provision and, very simply, restore trust and confidence, the committee recommended.

“The government must develop a standardised, national framework for the support that children with SEND can expect in school, long before requiring an EHCP, so that there can be confidence and clear lines of accountability,” said Helen.

“In the long term, a genuinely inclusive, well-resourced mainstream education system will bring down the desperate struggle to obtain an EHCP. This will also help stabilise the sector financially,” she added.