Leadership Focus journalist Nic Paton looks at how school closures and falling rolls are impacting both staff and pupils.

Impact of

school closure

AMARDEEP PANESAR,

FORMER HEAD TEACHER OF A PRIMARY SCHOOL IN NORTH LONDON

“I absolutely hit a wall; I suddenly felt I had lost the rhythm of my days,” explains Amardeep Panesar, describing how she felt when, at the end of the summer, her school – a primary school in north London – closed its doors.

Amardeep, now thankfully working as an interim consultant at a primary school in Milton Keynes, is by no means the only head teacher to have been forced to navigate what can be a disruptive, unsettling and emotionally – as well as operationally – challenging process for senior school leaders.

A recent report by London Councils has highlighted that most London boroughs are expecting to see a sharp decline in school rolls, from reception onwards, until at least 2027-28.

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

While falling rolls and school closures are becoming an especially acute problem in the capital, the demographic contraction we’ve seen in recent years – since the ‘bulge’ – is being felt by schools across the country, especially smaller and rural schools. And the impact on school leaders can be immense, as NAHT assistant general secretary James Bowen explains.

“School closures have a huge emotional impact, both for pupils and staff. If your school suddenly disappears, as a pupil, you have to find a new friendship group, and you may have to travel further,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“Some of the staff members will have been at the school for a very long time and dedicated decades of their life to it. The impacts can be enormous. School leaders, too, often develop a real emotional bond to their school.

“There can be a significant emotional toll for a school leader managing this process, for the same reason. Suddenly, they are managing a community of people who are either moving to a new site or won’t have a job. That can have a significant impact on you as a leader.”

For Amardeep, who was head teacher at her school for three years, the move to go through a closure process was still a shock, even though the roll had been falling for some time. “The school was already downsizing when I took on the headship; I was aware we were going from a two-form to a one-form entry, but I wasn’t expecting the school actually to close during my headship,” she says.

“Things very quickly escalated, for many reasons, and the local authority made the decision to close the school,” she adds, with a consultation taking place during the autumn and the school closing by the end of the school holidays in the summer term.

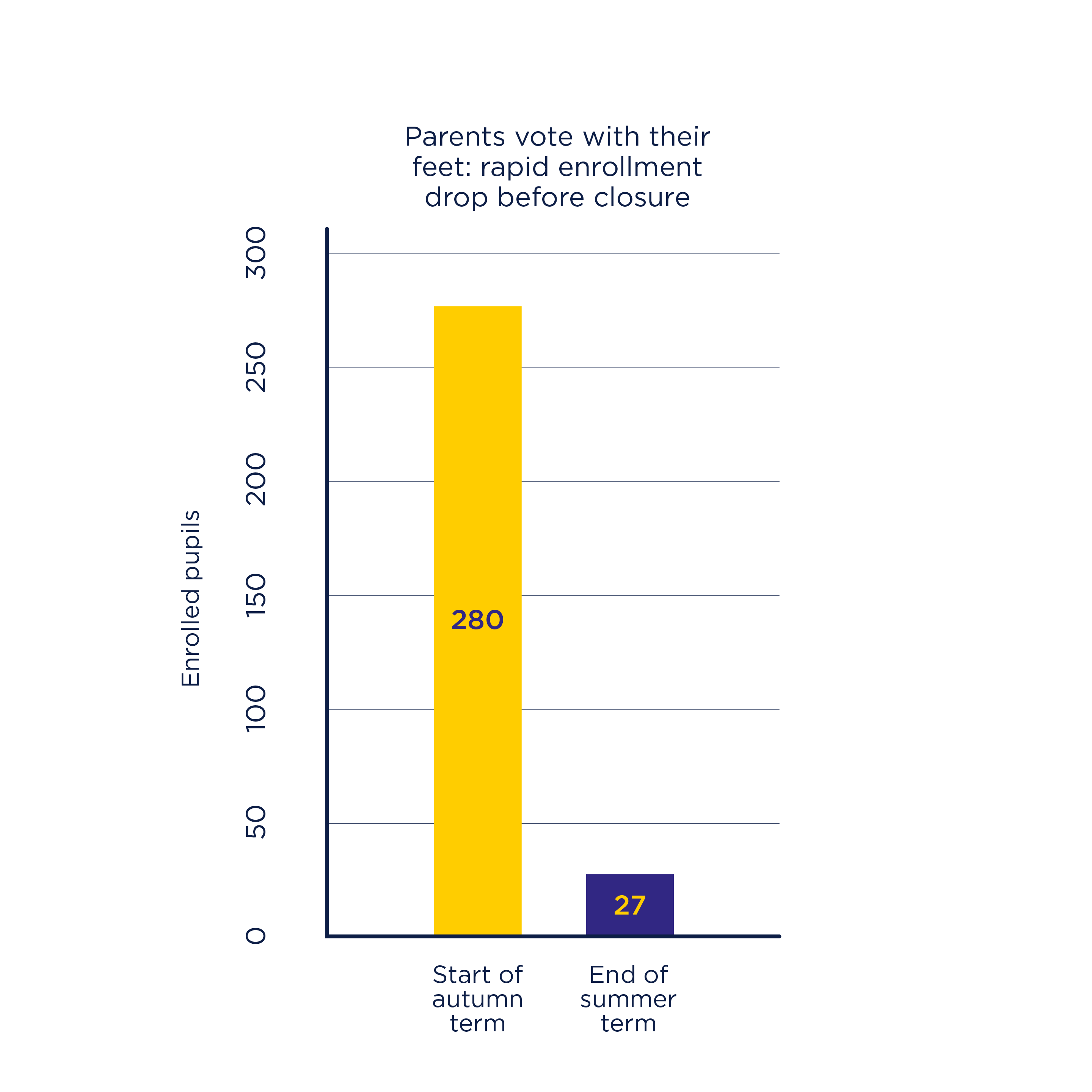

“The whole process really brought with it an additional load as a head teacher,” says Amardeep. “It made everything very unsettled. Even before the formal consultation started parents, understandably, began to remove their children from the school to alternative settings.”

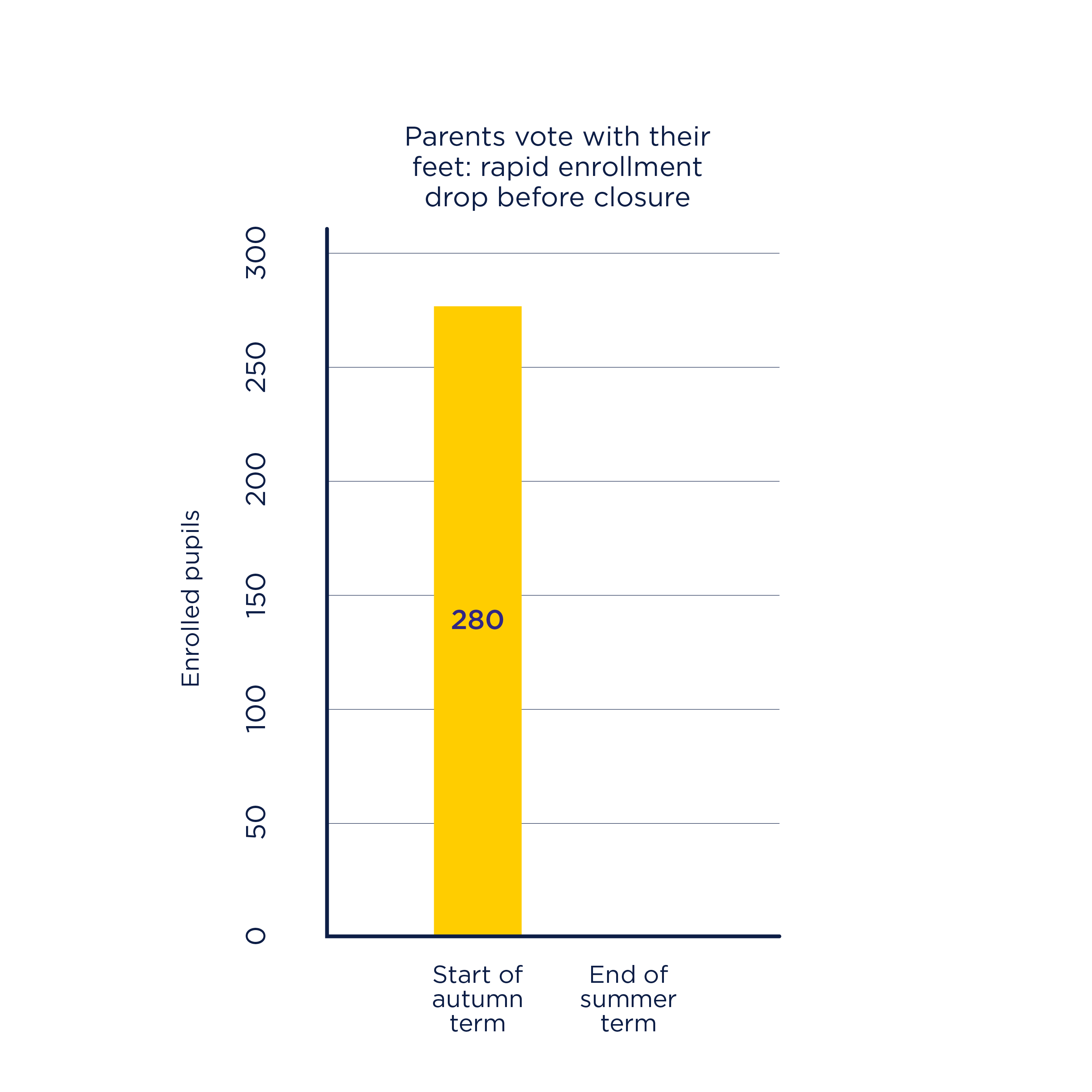

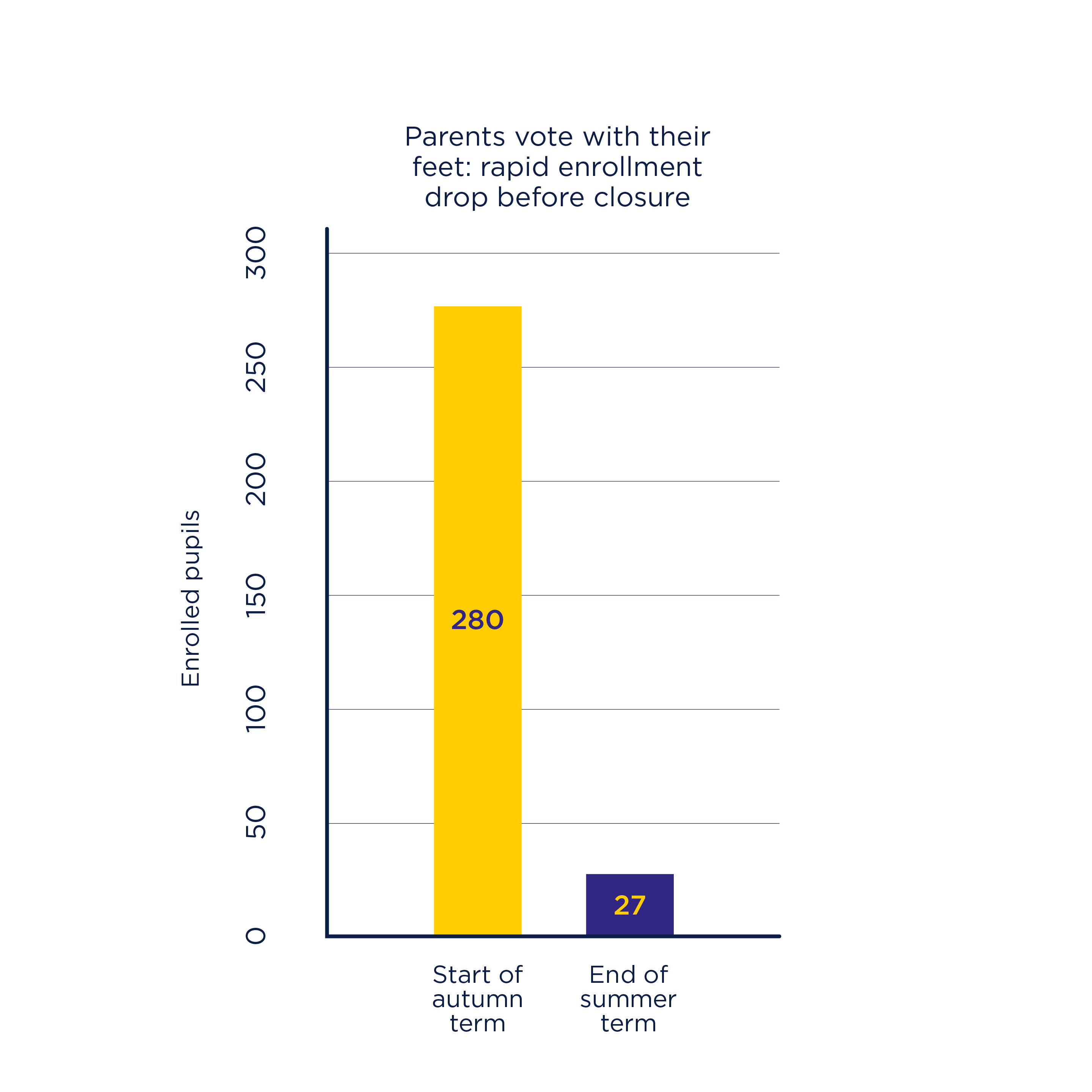

As a result, from having had some 280 children on roll at the start of the process, by the end of the summer term, parents had voted with their feet and the numbers were down to just 27. However, Amardeep professes pride in the fact that her team had a 100% success rate in placing children at alternative schools.

“We worked with the local authority in placing the children, which was, of course, our priority – and I have to say that was a really supportive part of the process. By May, all of our children had been placed in the right setting, including all our education, health and care plan children,” she explains.

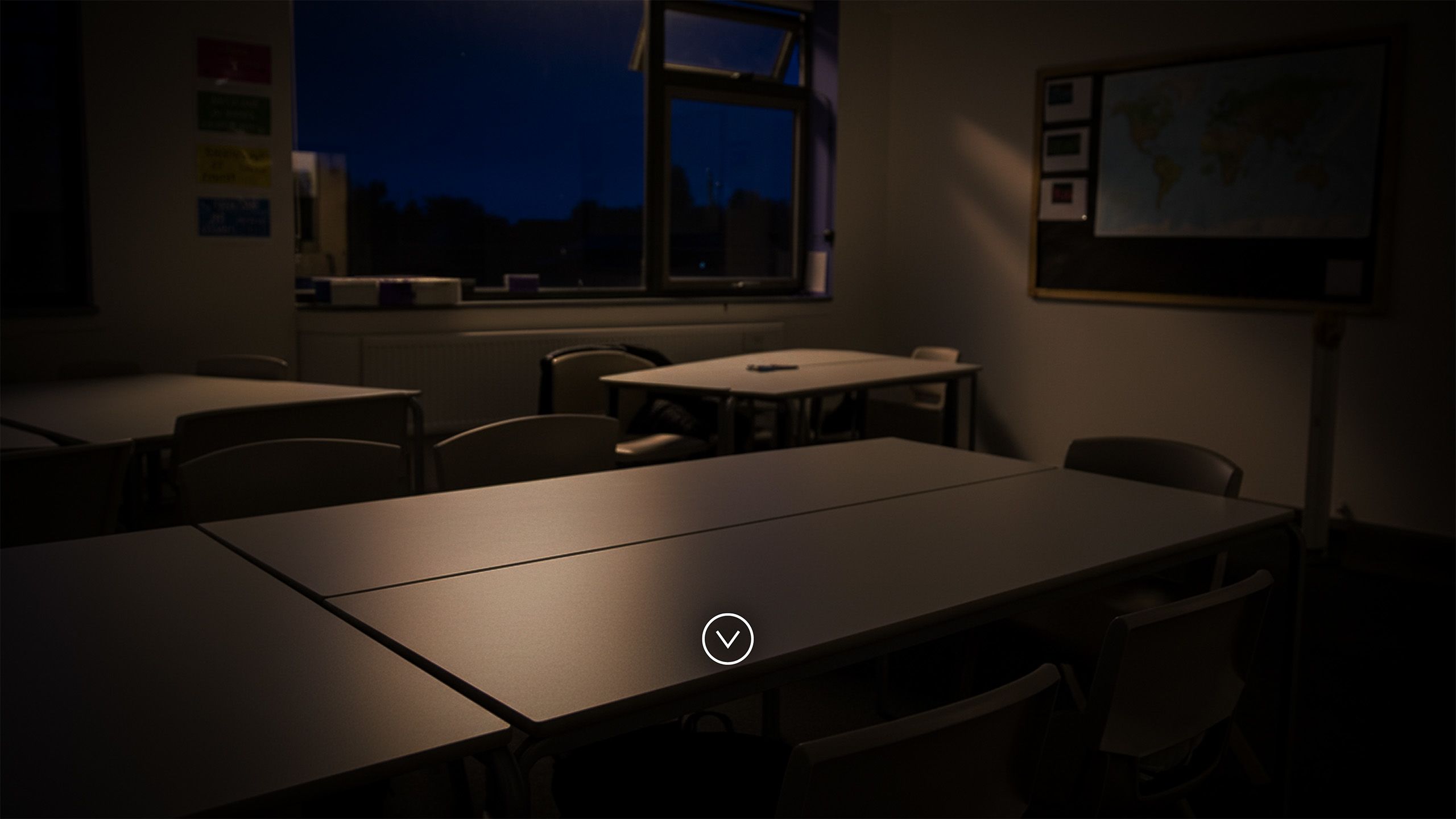

“In a way, the emotional fallout – for me – did not materialise until after the school had finally closed in September. You are in the job, and your job is to keep everybody going and keep everybody steady. Managing staff members’ mental health and well-being was the most challenging part of the job,” says Amardeep, as staff numbers fell from 54 to just seven in the final stages.

“We had voluntary and compulsory redundancies, which affected the older age group in particular. We had people who had been in their job for 25-30 years; it absolutely shook them. It affected their family, their income, their friendships and their lifestyle. You could just see it impacting them and their lives.

“My leadership very much became about looking after the staff and making sure they were OK; I worked right through the summer break, because we were contracted until 31 August, and there was the responsibility of the site and clearing out the resources for schools and communities. And then suddenly, it all ended; I found the first three weeks in September incredibly challenging. Because what do you do?” she adds, albeit eventually landing her current interim consultancy role at the beginning of October.

AMARDEEP PANESAR,

FORMER HEAD TEACHER OF A PRIMARY SCHOOL IN NORTH LONDON

“I absolutely hit a wall; I suddenly felt I had lost the rhythm of my days,” explains Amardeep Panesar, describing how she felt when, at the end of the summer, her school – a primary school in north London – closed its doors.

Amardeep, now thankfully working as an interim consultant at a primary school in Milton Keynes, is by no means the only head teacher to have been forced to navigate what can be a disruptive, unsettling and emotionally – as well as operationally – challenging process for senior school leaders.

A recent report by London Councils has highlighted that most London boroughs are expecting to see a sharp decline in school rolls, from reception onwards, until at least 2027-28.

JAMES BOWEN,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

While falling rolls and school closures are becoming an especially acute problem in the capital, the demographic contraction we’ve seen in recent years – since the ‘bulge’ – is being felt by schools across the country, especially smaller and rural schools. And the impact on school leaders can be immense, as NAHT assistant general secretary James Bowen explains.

“School closures have a huge emotional impact, both for pupils and staff. If your school suddenly disappears, as a pupil, you have to find a new friendship group, and you may have to travel further,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“Some of the staff members will have been at the school for a very long time and dedicated decades of their life to it. The impacts can be enormous. School leaders, too, often develop a real emotional bond to their school.

“There can be a significant emotional toll for a school leader managing this process, for the same reason. Suddenly, they are managing a community of people who are either moving to a new site or won’t have a job. That can have a significant impact on you as a leader.”

For Amardeep, who was head teacher at her school for three years, the move to go through a closure process was still a shock, even though the roll had been falling for some time. “The school was already downsizing when I took on the headship; I was aware we were going from a two-form to a one-form entry, but I wasn’t expecting the school actually to close during my headship,” she says.

“Things very quickly escalated, for many reasons, and the local authority made the decision to close the school,” she adds, with a consultation taking place during the autumn and the school closing by the end of the school holidays in the summer term.

“The whole process really brought with it an additional load as a head teacher,” says Amardeep. “It made everything very unsettled. Even before the formal consultation started parents, understandably, began to remove their children from the school to alternative settings.”

As a result, from having had some 280 children on roll at the start of the process, by the end of the summer term, parents had voted with their feet and the numbers were down to just 27. However, Amardeep professes pride in the fact that her team had a 100% success rate in placing children at alternative schools.

“We worked with the local authority in placing the children, which was, of course, our priority – and I have to say that was a really supportive part of the process. By May, all of our children had been placed in the right setting, including all our education, health and care plan children,” she explains.

“In a way, the emotional fallout – for me – did not materialise until after the school had finally closed in September. You are in the job, and your job is to keep everybody going and keep everybody steady. Managing staff members’ mental health and well-being was the most challenging part of the job,” says Amardeep, as staff numbers fell from 54 to just seven in the final stages.

“We had voluntary and compulsory redundancies, which affected the older age group in particular. We had people who had been in their job for 25-30 years; it absolutely shook them. It affected their family, their income, their friendships and their lifestyle. You could just see it impacting them and their lives.

“My leadership very much became about looking after the staff and making sure they were OK; I worked right through the summer break, because we were contracted until 31 August, and there was the responsibility of the site and clearing out the resources for schools and communities. And then suddenly, it all ended; I found the first three weeks in September incredibly challenging. Because what do you do?” she adds, albeit eventually landing her current interim consultancy role at the beginning of October.

Funding and

policy challenges

For NAHT, as well as the emotional and individual support for members, there are issues here around both the current roll-based funding of schools and, more widely, the potential loss of vital community assets.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman concedes that if rolls have fallen to the point where a school is no longer viable, then, clearly, “you can’t deny the economics of that”.

But, he adds, NAHT would nevertheless like to see a more flexible, nuanced approach taken by the government, or at least one that is less blunt. “There is an opportunity for the government here, I think. If we don’t take the money out of the school system, if we simply say, ‘This is the cost of education,’ then if a roll does shrink slightly, we have proportionately more per child and we can have some sensible conversations about which schools need to remain open, which schools need to merge and which schools need to close,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“Yes, if you have declining numbers of children coming to a school, you can’t go on forever. But very early conversations with the school, and with us as trade unions, about how we manage this are important. It is about not burying our heads in the sand until it is too late.

“The government also needs to consider its ambitions for how these buildings could be used. Could they perhaps become centres of the community, for other services? There will be some complex stuff in there, such as who is responsible for the buildings, so I’m not saying that’s easy. But I think we need to be a lot more innovative than simply saying we are going to close a site,” Paul adds.

ROB KELSALL,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

“We’re advocating that schools, as a national and community asset, are an invaluable resource,” agrees NAHT assistant general secretary Rob Kelsall. “We know pupil populations rise and fall. It is important, therefore, that a longer-term view is taken in terms of the sustainability of a school.

“Just because rolls are falling, let’s not make knee-jerk reactions to just close them and ship those children miles down the road to another school. Politicians should take the opportunity, with falling rolls, to address the fact that we have the largest class sizes in the developed world. Let’s take the opportunity to keep schools open as a resource, as a community asset,” he adds.

“We do know that, across the country, falling pupil numbers will put pressure on some schools, particularly smaller ones,” emphasises James. “Our policy response has been that just because pupil numbers are falling, this should not be used as a reason to reduce funding. There is a danger that the government could see this as a way to save some money because it would reduce the funding proportionately.

“What we’re saying is don’t do that. At the very least, retain funding levels as pupil numbers reduce because it would allow us to do things like reduce class sizes or enable pupils to receive slightly more funding. Essentially, use this as an opportunity rather than seeing it as a way of saving money,” he adds.

DAVE WOODS,

NAHT VICE-PRESIDENT AND EALING BRANCH SECRETARY

In London, factors such as covid-19, Brexit and the cost of living – housing and transport in particular – have all led to a flight from inner-London and its schools, highlights Dave Woods, NAHT vice-president and Ealing branch secretary.

“If you have a lot of people who are working in jobs that are paying minimum salaries, even if they’re paying the London Living Wage, it is still barely enough to run a household, plus all the other costs. So, people have just tended to move out,” he says.

“As soon as the consultation process starts, parents start withdrawing their children even more quickly because they want to secure their place somewhere else, very understandably. The numbers then dwindle even faster, and it makes the process almost inevitable,” he adds, echoing Amardeep’s experience.

“For staff, you get into the whole issue that good-quality, experienced ones are going to start to look much sooner. Or staff who are near the end of their career might just think, ‘Actually, I’ll just take what’s on offer.’ For the poor school leader, they often see it through to the end, to deliver this wind-down of the school.

“We’ve had head teacher colleagues in London who have found it very distressing. They put themselves last, and it doesn’t actually really hit them until pretty much the closure point. Often, they are left thinking, ‘What do I do next? Where do I go next?’

“We can’t stop the process from happening, but we’d like to develop a more inclusive strategy and a more holistic approach across the whole city. What plans, too, can be put in place for these sites when they do become vacant – and how can we anticipate this earlier so that other options, such as amalgamation, federation or whatever, can be considered before closure? What parents want is simply for their child’s local school to be close to where they live,” Dave adds.

For NAHT, as well as the emotional and individual support for members, there are issues here around both the current roll-based funding of schools and, more widely, the potential loss of vital community assets.

PAUL WHITEMAN,

NAHT GENERAL SECRETARY

NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman concedes that if rolls have fallen to the point where a school is no longer viable, then, clearly, “you can’t deny the economics of that”.

But, he adds, NAHT would nevertheless like to see a more flexible, nuanced approach taken by the government, or at least one that is less blunt. “There is an opportunity for the government here, I think. If we don’t take the money out of the school system, if we simply say, ‘This is the cost of education,’ then if a roll does shrink slightly, we have proportionately more per child and we can have some sensible conversations about which schools need to remain open, which schools need to merge and which schools need to close,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“Yes, if you have declining numbers of children coming to a school, you can’t go on forever. But very early conversations with the school, and with us as trade unions, about how we manage this are important. It is about not burying our heads in the sand until it is too late.

“The government also needs to consider its ambitions for how these buildings could be used. Could they perhaps become centres of the community, for other services? There will be some complex stuff in there, such as who is responsible for the buildings, so I’m not saying that’s easy. But I think we need to be a lot more innovative than simply saying we are going to close a site,” Paul adds.

ROB KELSALL,

NAHT ASSISTANT GENERAL SECRETARY

“We’re advocating that schools, as a national and community asset, are an invaluable resource,” agrees NAHT assistant general secretary Rob Kelsall. “We know pupil populations rise and fall. It is important, therefore, that a longer-term view is taken in terms of the sustainability of a school.

“Just because rolls are falling, let’s not make knee-jerk reactions to just close them and ship those children miles down the road to another school. Politicians should take the opportunity, with falling rolls, to address the fact that we have the largest class sizes in the developed world. Let’s take the opportunity to keep schools open as a resource, as a community asset,” he adds.

“We do know that, across the country, falling pupil numbers will put pressure on some schools, particularly smaller ones,” emphasises James. “Our policy response has been that just because pupil numbers are falling, this should not be used as a reason to reduce funding. There is a danger that the government could see this as a way to save some money because it would reduce the funding proportionately.

“What we’re saying is don’t do that. At the very least, retain funding levels as pupil numbers reduce because it would allow us to do things like reduce class sizes or enable pupils to receive slightly more funding. Essentially, use this as an opportunity rather than seeing it as a way of saving money,” he adds.

DAVE WOODS,

NAHT VICE-PRESIDENT AND EALING BRANCH SECRETARY

In London, factors such as covid-19, Brexit and the cost of living – housing and transport in particular – have all led to a flight from inner-London and its schools, highlights Dave Woods, NAHT vice-president and Ealing branch secretary.

“If you have a lot of people who are working in jobs that are paying minimum salaries, even if they’re paying the London Living Wage, it is still barely enough to run a household, plus all the other costs. So, people have just tended to move out,” he says.

“As soon as the consultation process starts, parents start withdrawing their children even more quickly because they want to secure their place somewhere else, very understandably. The numbers then dwindle even faster, and it makes the process almost inevitable,” he adds, echoing Amardeep’s experience.

“For staff, you get into the whole issue that good-quality, experienced ones are going to start to look much sooner. Or staff who are near the end of their career might just think, ‘Actually, I’ll just take what’s on offer.’ For the poor school leader, they often see it through to the end, to deliver this wind-down of the school.

“We’ve had head teacher colleagues in London who have found it very distressing. They put themselves last, and it doesn’t actually really hit them until pretty much the closure point. Often, they are left thinking, ‘What do I do next? Where do I go next?’

“We can’t stop the process from happening, but we’d like to develop a more inclusive strategy and a more holistic approach across the whole city. What plans, too, can be put in place for these sites when they do become vacant – and how can we anticipate this earlier so that other options, such as amalgamation, federation or whatever, can be considered before closure? What parents want is simply for their child’s local school to be close to where they live,” Dave adds.

Support and advocacy

MATTHEW WATERFALL,

NAHT SENIOR REGIONAL HEAD

For any school leaders going through this process – in London or elsewhere – the key is to recognise that you are not alone and that NAHT, locally, regionally and nationally, will be there for you, emphasises NAHT senior regional head Matthew Waterfall.

“NAHT has been campaigning about this for years. We want members to know that we are aware of it, that we are lobbying with London Councils and the Association of London Directors for Children’s Services, that we are campaigning for schools to retain their funding when pupil numbers begin to fall so that they have the resources needed to manage a difficult situation, and that we are calling for there to be a more uniform system of determining who is in scope.

“We would like, too, some more cross-borough working to make sure there is an orderly transition and that children are suitably allocated to their new school. But, most importantly, members need to be aware that they can call on us if they need advice and guidance,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“We have a network of strong branches in London, for example, that are on hand to assist members going through this. We can’t, of course, stop schools closing, but our branch networks can provide moral support and a friendly voice at the end of the phone. So, reach out to your branch officials if you need support. We also have a dedicated, professional team of officers who can provide assistance for more complicated issues, and there is also our specialist advice team,” Matthew adds.

Certainly, for Amardeep, the support she received from NAHT and – more widely – all her team received from their various unions, was invaluable. “It was good that all the unions pulled together in order to help everyone, because we were all in the same situation after all,” she recalls.

“We talk about well-being, and we talk about blocking out your time. It is the one thing that kept me sane. I go to the gym and CrossFit a lot and play badminton; those things have become essential. They are – yes – hobbies, but they became my therapy. That helps you to be there, to guide and support your colleagues.

“The role changes from being strategic to very operational, making sure everyone is OK and that everyone is functioning. But I found it doesn’t actually hit you until it’s concluded – in my case, in September – and suddenly it all goes quiet,” Amardeep adds in conclusion.

MATTHEW WATERFALL,

NAHT SENIOR REGIONAL HEAD

For any school leaders going through this process – in London or elsewhere – the key is to recognise that you are not alone and that NAHT, locally, regionally and nationally, will be there for you, emphasises NAHT senior regional head Matthew Waterfall.

“NAHT has been campaigning about this for years. We want members to know that we are aware of it, that we are lobbying with London Councils and the Association of London Directors for Children’s Services, that we are campaigning for schools to retain their funding when pupil numbers begin to fall so that they have the resources needed to manage a difficult situation, and that we are calling for there to be a more uniform system of determining who is in scope.

“We would like, too, some more cross-borough working to make sure there is an orderly transition and that children are suitably allocated to their new school. But, most importantly, members need to be aware that they can call on us if they need advice and guidance,” he tells Leadership Focus.

“We have a network of strong branches in London, for example, that are on hand to assist members going through this. We can’t, of course, stop schools closing, but our branch networks can provide moral support and a friendly voice at the end of the phone. So, reach out to your branch officials if you need support. We also have a dedicated, professional team of officers who can provide assistance for more complicated issues, and there is also our specialist advice team,” Matthew adds.

Certainly, for Amardeep, the support she received from NAHT and – more widely – all her team received from their various unions, was invaluable. “It was good that all the unions pulled together in order to help everyone, because we were all in the same situation after all,” she recalls.

“We talk about well-being, and we talk about blocking out your time. It is the one thing that kept me sane. I go to the gym and CrossFit a lot and play badminton; those things have become essential. They are – yes – hobbies, but they became my therapy. That helps you to be there, to guide and support your colleagues.

“The role changes from being strategic to very operational, making sure everyone is OK and that everyone is functioning. But I found it doesn’t actually hit you until it’s concluded – in my case, in September – and suddenly it all goes quiet,” Amardeep adds in conclusion.

Lessons from the devolved nations

LAURA DOEL,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY (WALES)

As with London, a number of local authority areas in Wales are reporting falling pupil numbers, highlights NAHT national secretary (Wales) Laura Doel.

“That, of course, puts a strain on the viability of schools. What we also have in Wales is local authorities that are funded per pupil based on the number of children in that local authority area. That money goes directly to the schools and so, if you have falling rolls, you have falling funding,” she points out.

“But that sits completely at odds with the Welsh Government’s initiative for community-focused schools: that schools should be the focal point of every community, that they should offer wider services beyond education, and that they should be the hub for local authority services. Yet, they are not prepared to put any extra money in. So, there is a bit of a double-edged sword here.

“It cannot be a hard-and-fast rule that if you have 'x' number of pupils, the school is no longer viable. You need to consider the exact context of that community before taking any arbitrary decisions. It is a very mixed picture,” Laura adds.

DR GRAHAM GAULT,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY (NORTHERN IRELAND)

In Northern Ireland, conversely, smaller and rural schools will often be protected from closure. Although this tends to be for historic reasons specific to Northern Ireland, there is perhaps a wider lesson that can be taken away here for English schools, argues NAHT national secretary (Northern Ireland) Dr Graham Gault.

“We do have a number of smaller schools that have been earmarked for closure under what is called ‘Area Planning’. In Northern Ireland, however, there is also the unique demographic and community context of our still-divided society to take into account,” he points out.

“This means you can have a small village with two relatively small schools, which could, from a purely financial perspective, be amalgamated. But they probably never will be because of their historic political and religious significance within their own community in terms of preserving a small community’s sense of identity and civil ownership. So, we have that as a dynamic, which has actually been positive in terms of protecting schools from closure and enabling communities still to benefit from them.

“For me, the lesson for England is the importance of these decisions not being made solely on the basis of money and the importance of community interest, identity and cohesion being part of the equation, too,” Graham adds.

Lessons from the devolved nations

LAURA DOEL,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY (WALES)

As with London, a number of local authority areas in Wales are reporting falling pupil numbers, highlights NAHT national secretary (Wales) Laura Doel.

“That, of course, puts a strain on the viability of schools. What we also have in Wales is local authorities that are funded per pupil based on the number of children in that local authority area. That money goes directly to the schools and so, if you have falling rolls, you have falling funding,” she points out.

“But that sits completely at odds with the Welsh Government’s initiative for community-focused schools: that schools should be the focal point of every community, that they should offer wider services beyond education, and that they should be the hub for local authority services. Yet, they are not prepared to put any extra money in. So, there is a bit of a double-edged sword here.

“It cannot be a hard-and-fast rule that if you have 'x' number of pupils, the school is no longer viable. You need to consider the exact context of that community before taking any arbitrary decisions. It is a very mixed picture,” Laura adds.

DR GRAHAM GAULT,

NAHT NATIONAL SECRETARY (NORTHERN IRELAND)

In Northern Ireland, conversely, smaller and rural schools will often be protected from closure. Although this tends to be for historic reasons specific to Northern Ireland, there is perhaps a wider lesson that can be taken away here for English schools, argues NAHT national secretary (Northern Ireland) Dr Graham Gault.

“We do have a number of smaller schools that have been earmarked for closure under what is called ‘Area Planning’. In Northern Ireland, however, there is also the unique demographic and community context of our still-divided society to take into account,” he points out.

“This means you can have a small village with two relatively small schools, which could, from a purely financial perspective, be amalgamated. But they probably never will be because of their historic political and religious significance within their own community in terms of preserving a small community’s sense of identity and civil ownership. So, we have that as a dynamic, which has actually been positive in terms of protecting schools from closure and enabling communities still to benefit from them.

“For me, the lesson for England is the importance of these decisions not being made solely on the basis of money and the importance of community interest, identity and cohesion being part of the equation, too,” Graham adds.